From The Soho News (June 24, 1981). — J.R.

Juke Girl is an unassuming Warner Brothers program filler — a Depression movie made in 1942 starring Ronald Reagan as a young socialist hero from Kansas and Ann Sheridan in the tough-and-tender title part. It reminds me of something that Manny Farber said in a recent lecture about what people looked like in 30s films, when “every shape was legitimate,” as opposed to the more constricting notions about what people are supposed to look like in 70s films — a model that remains in force today.

As a general rule of thumb, I think one can argue pretty plausibly that any Warner Brothers Depression film, however minor, has something going for it on a social/aesthetic level that can’t be found in any over-publicized New Hollywood glitz production, however major. This is less monolithic a judgment than it sounds, especially if one considers the radically different notions of audience involved. A sense of community and closeness that’s founded on mutual dependence in all the meat-and-potatoes Warners staples — kept taut, dynamic and authentic by a snappy, mistrustful stream of wisecracking dialogue that breezes through this ambiguously charged atmosphere — harks back to an era when people when to movies to see other people rather than to get away from them.

Every Thursday through the end of August at the Thalia, you can see whether I’m right or not by going to see a double feature of relatively obscure Warner Brothers feature (a rare privilege), and comparing any of them — I mean any — to any of the brand-new obligatory streamliners playing first-run downtown. Not knowing too much about what you’re going to is part of what I’m recommending, and an important part. Of the more than two dozen features that James Harvey has selected, I’ve seen about a quarter. I regret the absence of a personal favorite, Blonde Crazy, a swell James Cagney and Joan Blondell vehicle which could have made a dynamite duo with Hard to Handle [see below] (another fine Cagney quickie, which is being shown on August 27, with William Wellman’s intriguing-sounding College Coach). But the point of a series like this one is everyone’s discoveries — anyone’s — not mine or Harvey’s.

The Paris Cinematheque educated a generation of filmmakers with just such a strategy of adventure. It’s harder to pull off anything similar in this town, where art isn’t even news now. (Critics clamoring for “adult” entertainment flee in terror from the new Godard, which is precisely too grown-up to make it onto any front pages.) By contrast, a new blockbuster, even in 70mm and Dolby, promises to be only a midway station and momentary rest-stop in a long mass-communication trek leading from promotion to spin-off products — an ad to end all other ads (and thereby justify the others by absorbing them). George Orwell put it very succinctly in 1947: “Much of which goes by the name of pleasure is simply an effort to destroy consciousness.” What better description of Raiders of the Lost Ark or any of its mercenary brothers? (Unlike Numero Deux, it has no sisters.)

Blockbusters either forbid discoveries or impose them, which comes to the same thing. They rarely qualify as human encounters. In the Warners series, on the other hand, your discoveries don’t have to be mine (and vice versa), but we can still feel like we’re watching the same movie together — not merely responding to the same effects and other Pavlovian signals.

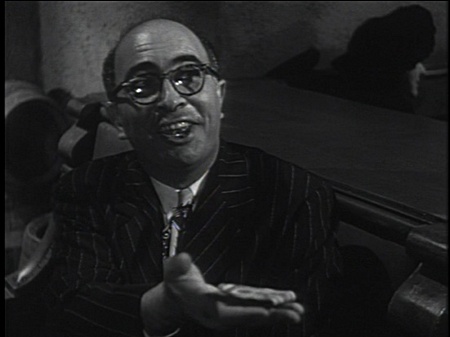

Juke Girl was scripted by A.I. Bezzerides (working from Kenneth Garnet’s adaptation of a story by Theodore Pratt), a remarkable scriptwriter who remains to be properly discovered in film history. [See photograph below, of his cameo in On Dangerous Ground.] The only copious references to Bezzerides in print that I can find in my house are a couple in French and several in Joseph Blotner’s biography of Faulkner (a close friend of Bezzerides in Hollywood during the 40s). Yet he’s the man who scripted or coscripted imaginative, original movies like They Drive By Night and Thieves’ Highway (two other trucking movies), On Dangerous Ground, Track of the Cat, Kiss Me Deadly, and William Faulkner: A Life on Paper (a first-rate, two-hour documentary shown on WNET a year and a half ago). Blotner reports thatr in the mid-40s, “Albert Isaac Bezzerides was a strong, dark, massive man of 36. Born in Turkey of a Greek father to an Armenian mother, he was raised in Fresno and educated as an engineer at Berkeley.”

You certainly don’t have to know a whit of this in order to discover and enjoy Juke Girl; it’s just one of many possible threads that make it more fun to follow. (The film’s set in Cat-Tail, Florida, “largest vegetable shipping point in the world,” and the produce market in Atlanta, while the 1949 Thieves’ Highway — with a similar protest plot about an exploitative packing-house boss, based on a Bezzerides novel called Thieves’ Market — revolves around San Francisco’s produce market on the opposite coast. And as Greg Ford points out to me, both movies have major characters named Nick Garcos — a European father figure to Reagan and Sheridan in Juke Girl, played by George Tobias, and the ex-GI hero played by Richard Conte in Thieves’ Highway.)

So there are plenty of reasons to see Juke Girl, which is playing on the 25th with Baby Face (a 1933 Barbara Stanwyck vehicle with George Brent and John Wayne). There’s Sheridan singing a chorus of “I Hate Love But I Love To Hate It” in front of a jukebox, getting fired by a man named Muck-Eye after she helps out the poor farmers and telling Reagan, “Look, Steve, you still got Kansas in your hair. Every time you see a patch of land, you want to settle down.” There’s a little girl named Skeeter and an older man in the same shantytown (Alan Hale, see below) called Yippy. There’s Reagan defiantly swiping a packing-house truck to help Nick Gavros pack his tomatoes, one of which he subsequently crushes into the capitalist villain’s face. But you should go and discover your own reasons. And check out the future Thursday programs for what are sure to be more pleasant surprises, none of which can be spoiled by any media saturation or advance hype — movies that can belong to you rather than their makers.

***

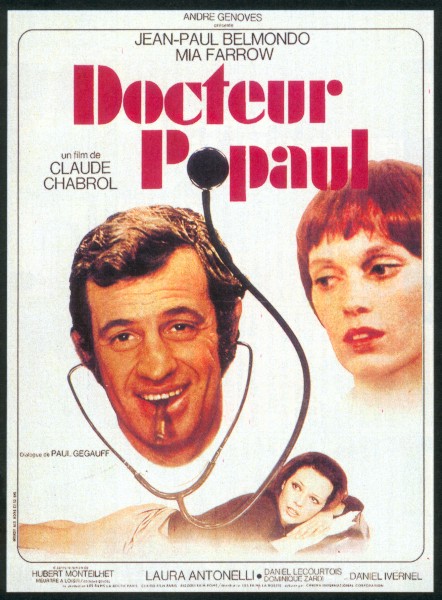

More than eight years ago, while discussing the French passion for Jerry Lewis in a “Paris Journal” for Film Comment, I cited the latest Chabrol film, Dr. Popaul, for what seemed at the time to be traces of his local influence — the eyeglasses and buck teeth assigned to Mia Farrow (along with leg braces) to make her look like Lewis’s Julius Kelp in The Nutty Professor, and a string of sight-gags assigned at one point to Jean-Paul Belmondo, the hero. I noted that Dr. Popaul struck me as less worthy of American release than Chabrol’s previous Ophelia, La Rupture, or Juste Avant la Nuit — affirming that I preferred Lewis’s originals to Chabrol’s pastiches — but predicted that “if and when Dr. Popaul should open in the states…it will receive more attention and respect than any of the last few films directed by Lewis.”

Well, now that Dr. Popaul has at last turned up, inexplicably titled High Heels — on a very odd double-bill with Dandy, the All-American Girl (see below) on the 26th and 27th, in the Thalia’s ongoing series of New York and U.S. premieres of buried or ignored films every Friday and Saturday through July 11 — the Lewis connection seems much more remote. Recalling that Popaul is the name of the title character played by Jean Yanne in Chabrol’s Le Boucher, I assume there is some reason to view this as a personal directorial project; yet what I see reveals such directorial contempt or indifference toward the material — above all, the actors — that the script often seems to be hurled at one rather than simply interpreted or delivered. Like many failures, however, it is immensely instructive.

Overlit like Bavarian softcore porn, with bits of mugging from Belmondo that might seem a little excessive in a Three Stooges comedy, Dr. Popaul relates the story of Dr. Paul Simay, who believes as a youth that “moral beauty exists only in ugly women,” and inaugurates a competition with his buddies to see who can screw the most hideous female. Picking up Christine Dupont for a one-night stand on a Tunisian holiday, and offended when she offers him money afterwards, Simay accidentally re-encounters her in Bordeaux a year later and is induced by her wealthy father to marry her and run his local clinic. Aroused by Christine’s beautiful sister Martine (Laura Antonelli, natch), he contrives to conduct a long-term affair with her — keeping Christine drugged with sleeping pills, disposing of Martine’s suitors and even tricking Martine into having their child (with the help of the clinic) — until…

If this sounds a lot like one of scriptwriter Paul Gegauff’s celebrated macho-glib conceits — he scripted all the most scabrous (and most of the best) Chabrol movies, virtually playing himself (opposite ex-wife Daniele) in Une Partie de Plaisir, and played Mozart in the farmyard in Godard’s Weekend — what is one to make of the casting of Mia Farrow as Christine, which is like getting Jeanne Crain to play a black in Pinky? (Her voice is dubbed in French, by the way, while the subtitles occasionally offer further displacement — my favorite is translating “sil vous plait” as “Do you speak English?”) Yet the interesting thing about this paradoxically self-destructing self-ingratiation (a central Gegauffian theme, it appears) is that it extends the obsessions of minor Truffaut, like the subsequent The Man Who Loved Women, past the point where they could possibly be charming or tolerable or even palatable — a sensibility that, far from protecting itself, its trying its damnedest to gross itself out, and failing spectacularly (although it may succeed with us).

If only the film were more consistent about its passionate misanthropy and cynical self-hatred, it might have at least the status of an anti-masterpiece. Alas, Belmondo’s dumb-ass enactments of slapstick (he runs over somebody in a tractor — it’s supposed to be funny) or all the presiding officials in the nightmare his character has about his own trial (including a homophobic version of a gay magistrate) and too indifferently frenetic to qualify.

***

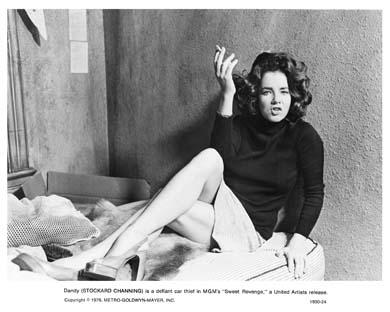

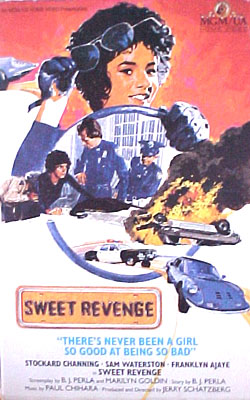

The failure of Dandy, the All-American Girl is a much more honorable one, and one that leaves me with some genuine regrets. On the face of it, watching Stockard Channing and Franklyn Ajaye (who played T.C., the guy with big Afro, in Car Wash) in a scene cowritten by Marilyn Goldin and shot by Vilmos Zsigmond sounds like a plausible idea of happiness. But something misses, or is missing, and I suspect that it has something to do with the apparent failure of the director, Jerry Schatzberg, to work as a catalyst and make me believe in it all. Actually, at odd junctures this movie appears to be remaking an even worse Truffaut movie, Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me, except in this case the remake seems underdone rather than excessive.

Schatzberg has already shown a certain affinity for poetic Skid Row landscapes and some of the more futile vicious circles of American poverty — a feeling that’s much more apparent, I think, in the Nelson Algrenesque pathos of Scarecrow than in a relatively academic exercise like Panic in Needle Park, despite the disconcerting Hollywood lip gloss that’s fitfully evident in his work (such as the use of music in Dandy). The pain of rootlessness in his movies may be real enough, but in sketching out the rudiments of a fictional world, he abandons these roots at his own peril.

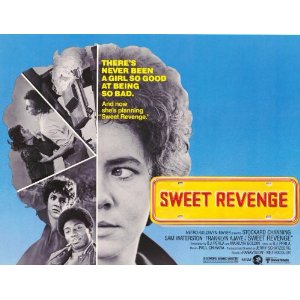

Somewhere behind the realization of Dandy (or Sweet Revenge, as it’s been retitled) there seems to be the potential workings of an all-American theme — the obsessive car thief as existential heroine (you are what you drive; or sweet revenge, as the motto on Ajaye’s Cadillac has it), with perhaps just a soupcon of Breathless (the hot-wiring ritual) and Two-Lane Blacktop (Warren Oates’ compulsive self-reinventions, which are themselves reinventions of scripwriter Rudolph Wurlitzer out of his novel Nog — a precursor of Channing’s fibs about her criminal past). But the forms of both these earlier movies are predicated on non-stop flow, while Dandy commits the error of meandering and stalling when it should be going places. How much of this is due to the B.P. Perla script revised by Goldin and how much is due to Schatzberg is impossible for me to determine, but there’s an unmistakable sense of absence in the plot and relationships that comes across as a gap in imagination. (The absence of sex in the film, on the other hand, is much more interesting and defensible.) Not even a spectacular car crash toward the end can make up for the “unfinished” aspect in all the characters.

A curious coincidence about Dandy and Popaul: both feature concerto-like sequences for their title leads meant to show off their versatility by rushing them through a battery of guises, yet staged in such a way that neither is able to score. Chabrol gives Belmondo far too much rope in his solipsistic courtroom nightmare, while Schatzberg seems to give Channing too little. As Dandy assumes a set of identities in a set of manuevers designed to filch her way to possessing her dream Dino Ferrari, each promising sketch fades abruptly from view before it’s possible to have any fun with what the actress is doing. (She may keep victimizing fall-guy lawyer Sam Waterston — sort of like the way that Bernadette Lafont keeps fooling Claude Brasseur in Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me — but the movie gives her an even harder time, denying her even a coherent past.) The same thing happens unfortunately with the striking Tacoma and Seattle locations, which are never explicitly identified in the film; had I known where I was, I might have somehow been able to do more with Zsigmond’s fragrantly rundown and weedy glimpses.