Reposted to mourn the death in 2015 of a titan, at age 106. From the July-August 2008 Film Comment, with the subhead “Negotiating the singular career of Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira on the eve of his 100th birthday “. — J.R.

Films, films,

The best resemble

Great books

That are difficult to penetrate

Because of their richness and depth.

The cinema isn’t easy

Because life is complicated

And art indefinable.

Making life indefinable

And art

complicated.

— Manoel de Oliveira, “Cinematographic Poem,” 1986 (translated from the Portuguese)

Since this century has taught us, and continues to teach us, that human beings can learn to live under the most brutalized and theoretically intolerable conditions, it is not easy to grasp the extent of the, unfortunately accelerating, return to what our 19th-century ancestors would have called the standards of barbarism.

— Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991

To insist that all great filmmakers contain multitudes is to risk a counter-response — that the same might equally be said of the not-so-great. Just as much labor can be expended on bad work as on good, and this applies to the labor of viewers and filmmakers alike. Life and art are both complicated, as Manoel de Oliveira points out, but that doesn’t necessarily make them interesting.

And so, from a practical standpoint, I’m afraid it won’t do to argue that lingering skeptics who still dispute Oliveira’s greatness simply need to see more of his films, especially because this advice usually leads to their seeing more of his bad stuff. Familiarity with Oliveira’s work as a whole does have its compensations, such as recognizing and enjoying his repertory company of actors, who seem every bit as loyal as Ford’s or Bergman’s, and include stalwarts Luís Miguel Cintra (17 films), Leonor Silveira (16 films), and Oliveira’s grandson Ricardo Trepa (13 films). But this doesn’t necessarily redeem his less scintillating features. And you don’t have to look far to find a bad Oliveira film — or at the very least boring (such as The Convent), pretentious (The Divine Comedy), or slight (Christopher Columbus, The Enigma), not to mention difficult (almost anything). This problem is compounded by the fact that some of Oliveira’s lesser efforts are the easiest to see, probably because they often feature stars.

These films are also usually the talkiest, as well as the ones in which Oliveira’s ideas — cinematic as well as thematic — seem too sketchy to sustain feature length, perhaps helping to explain why he sometimes alternates the gab with extended musical performances and/or prolonged establishing shots. The Letter (99) and Belle Toujours (06), for example, have their charms and fascinations, to be sure, but I’d hate having to use either one to support claims for Oliveira as a major figure.

The former transplants to the late 20th century Madame de Lafayette’s The Princess of Clèves, written in 1678 and commonly described as the first great short novel in French — a tale about the self-abnegating love of the highly principled, and married, heroine (Chiara Mastroianni) for the Duke of Nemours. (Reportedly, the idea for both reading and adapting this novel came about two decades earlier, from Oliveira’s principal French collaborator, translator, and exegete Jacques Parsi. Knowing the director’s fascination with the theme of frustrated love, he also suggested Paul Claudel’s The Satin Slipper.)

Part of the promising and initially amusing joke here appears to be the notion that aristocrats and their fussy distinctions hardly change at all from one century to the next — a conceit that works only if you don’t think about it too much. The other part is giving the role of the Duke to Portuguese pop star Pedro Abrunhosa, a dour, poker-faced dandy who hails from Porto, Oliveira’s hometown. Known for never removing his sunglasses, he plays himself à la Dean Martin in Kiss Me, Stupid.

Yet the campy humor of this double conceit extended over 105 minutes is so dry that it ultimately becomes arid. Oliveira neither runs nor plays with it; he dully plows ahead like a bulldozer, leading one to wonder eventually whether he has forgotten that the idea is supposed to be funny and ironic. And Momento, the surprisingly conventional and humorless music video that Oliveira made with Abrunhosa three years later, makes one wonder if he ever intended any sort of joke to begin with.

There’s a similar mulishness in Belle Toujours — an unlikely sequel/speculative footnote to Belle de jour that, unlike Buñuel’s work, has more to do with class than with sex, and whose only authentically Buñuelian touch involves the absurdist appearance of a chicken at a climactic moment. In the original film, Séverine (Catherine Deneuve), a frigid bourgeois housewife who loves her husband Pierre (Jean Sorel), gets an afternoon job at a high-price brothel in order to satisfy her masochistic desires — a secret discovered by Pierre’s friend Henri (Michel Piccoli), a rakish brothel customer. After Pierre is shot by one of Séverine’s jealous clients, leaving him permanently mute and paralyzed, Henri announces that he’ll tell Pierre everything, but we (and she) can’t be sure whether or not he actually does.

Oliveira, who couldn’t persuade Deneuve to play Séverine again, got Bulle Ogier, the female lead in his My Case (86), to assume the role. Beside the fact that she never comes across as the same character (a difference in conception that goes beyond casting), the story’s focus has shifted to Henri (Piccoli again). He chases after the reluctant Séverine for most of the movie to invite her to a swank dinner, which she finally agrees to attend because she wants to discover whether he did in fact tell Pierre the truth 40 years earlier. As Henri pontificates to a young barman (Ricardo Trepa), he portrays Séverine as a masochist who became a sadist in order to work through her love for her husband. Yet it’s his own unacknowledged sadism and glib narcissism that dominate the story — even though Oliveira, judging by interviews, appears to think that the film is mainly about Séverine. One might even argue that some “civilized” form of misogyny is the main aristocratic attribute on display here, just as “civilized” xenophobia and/or misanthropy may be the key form of disdain in A Talking Picture (03), another star-laden production.

In sum, you might say that there’s some sort of joke at play in The Letter and Belle Toujours, but an extremely private one in both cases, and without a clearly demarcated punchline. Oliveira’s apparent remoteness from these characters (apart from his seeming complicity with Henri) and the audience creates a yawning distance that at times seems to define his method. There are plenty of attractive distractions along the way, such as the musical interludes in both films, e.g., the performance of the second and third movements of Dvorák’s Eighth Symphony at the Paris concert that opens Belle Toujours, where Henri first sights Séverine. But the fact that they often register as distractions rather than as essential narrative or nonnarrative forays is part of the problem.

It also won’t do to try to clinch any briefs on Oliveira’s behalf by pointing out that he’ll be a century old this coming December. This is impressive in its own right, and makes his ongoing productivity all the more remarkable — though he’s pointed out himself that it’s largely been his filmmaking that has been keeping him alive. Even so, this doesn’t automatically validate the work being produced, at least beyond proposing that he may actually have more to tell us about the 19th century than James Ivory. Like Oliveira’s celebrated early stints as a champion pole-vaulter, diver, and race-car driver, you might say that his age adds more to his legend than to any better understanding of his filmography. (Some Oliveira fans seem to value Christopher Columbus, The Enigma chiefly because Oliveira, as lead actor, can be seen driving a car in it. I suppose one could also relate Oliveira’s principal assertion in this 75-minute film — that Christopher Columbus was a Portuguese Jew — to John Malkovich’s theory in The Convent that Shakespeare was a Spanish Jew, but I’m happy to leave the elaboration of this cross-reference to others.)

The son of a prominent industrialist — the first Portuguese manufacturer of electric lamps — Oliveira was an athlete, film actor (who appeared in the first Portuguese talkie), and college dropout who also helped run his father’s factories and took over a farm inherited by his wife when he wasn’t trying to make movies. But even though he finished his first film — the documentary short Labor on the Douro River (31) — when he was 23, over a decade would pass before his first feature, then a whopping 21 years more before his second.

If he deserves to be regarded as a master — and I believe he does — his mastery belongs partially in an eccentric category of his own invention, comparable to that of Thelonious Monk as an idiosyncratic jazz pianist. And it’s a mastery of sound and image that took shape fairly early — even though, as a director of actors, his foregrounding of artificial styles of performance doesn’t always enhance the technical gifts of his players. A few of Oliveira’s films are worth seeing principally for their actors: Voyage to the Beginning of the World (97) offers Marcello Mastroianni’s last screen performance (as an Oliveira surrogate); the all-star cast of A Talking Picture includes Catherine Deneuve, John Malkovich (in a hilarious turn as a charming if self-absorbed American cruise ship captain), Irene Papas, Stefania Sandrelli, and Leonor Silveira; Trepa’s best turn probably comes in the decorous but static The Fifth Empire, in which he plays clueless, despotic King Sebastian I (1544–78); and Michel Piccoli is especially fine in representing the joys and sorrows of getting old in I’m Going Home (01), perhaps the most accessible of Oliveira’s fiction films. But none of these is exactly characteristic.

Making my strongest claims for Doomed Love and Benilde isn’t likely to stir up many disputes. But this is partly because outside of scattered retrospective screenings, these features are almost impossible to see. Neither has ever been released on VHS or DVD anywhere in the world, and even if you want to try to track down Inquietude (98), which is nearly as good, you’ll have to settle for French subtitles if, like me, you don’t understand Portuguese.

The language barrier represents only one of many obstacles that stand between Oliveira and his audiences. A major strength of Randal Johnson’s recent book on the filmmaker, the first in English, is that it guides us through the features up through Belle Toujours and most of the 20 or so shorts and documentaries with all the essential contextual information, making it possible in many cases to follow the basic thrust of even those films that aren’t available on DVD with English subtitles. In this respect, besides being up to date, Johnson’s book has proved more useful than the five French books on Oliveira that I’ve acquired, all published between 1988 and 2002; in comprehensiveness, it’s topped only by the mammoth catalog produced for a tribute at the Torino Film Festival in 2000.

But certain other cultural barriers persist. No less formidable are issues involving class (Oliveira’s aristocratic background), political orientation (never directly stated in any of his films), the history of Portugal in the 20th century (especially the aforementioned dictatorship), and history in general (specifically, how one situates Oliveira, a 19th-century modernist, in relation to any particular period, past or present).

Indeed, another off-putting aspect of his career is its highly asymmetrical shape. He started out like Dreyer with an overall average of one feature per decade for half a century, then continued with about one feature per year ever since. It’s true that his initially sparse output can largely be attributed to the constraints of Salazar’s right-wing dictatorship, which lasted from 1926 to 1974, and that the fairly steady flow of work afterward can largely be attributed to the resourcefulness of Paolo Branco, who produced all of Oliveira’s films from Francisca in 1981 through The Fifth Empire in 2004. Yet the facts that Oliveira’s mastery as well as his modernism were firmly established in Benilde (75) and Doomed Love (78), before Branco came along, and that his near-annual output has continued since they parted company, only confirm that any simple cause-and-effect explanations of his unusual oeuvre are likely to be untrustworthy.

Let’s consider briefly the first three of these issues. (The fourth will be addressed a little later.) Despite some shared (and mutually avowed) cinematic influences, such as Bresson and Straub-Huillet, Oliveira and Pedro Costa might be said to occupy opposite ends of the spectrum of Portuguese culture in terms of the respective milieus of most of their films — rich versus lumpen-proletarian. The working-class milieus of Oliveira’s first two features, Aniki-Bóbó (42) and Rite of Spring (63), and his subsequent A Caixa (“The Box,” 94), can’t of course be factored out. But these three features, which have practically nothing else in common with one another (and even less in common with any of Costa’s films), are all atypical of Oliveira’s work, comprising, respectively, a neorealist children’s film, a documentary following a rural Passion play (à la Flaherty, with deliberate restagings and re-creations), and an adaptation of a play loosely resembling Elmer Rice’s Street Scene.

The elusiveness and ambiguity of Oliveira’s politics may partly derive from survival tactics during a half-century of living under the repressive regime of Salazar’s Estado Novo (New State). But one can’t necessarily conclude from this that Oliveira was simply or only a victim of the Estado Novo, even if, like many others, he was briefly jailed at one point (as he mentioned when he visited Chicago in 2005). Johnson reports that the occupation of the Oliveira dry-goods factory in Porto by leftists during the 1974 revolution led to its eventual bankruptcy and Oliveira losing “almost all of his personal assets, including the house where he had resided since 1940.” The fact that both a conservative devout Catholic like Paul Claudel and a leftist atheist scamp like Buñuel belong to his personal pantheon only begins to suggest that whatever his political positions might be, they aren’t likely to be simple.

The same goes for Oliveira’s mixed credentials as an avant-gardist. It’s been a quarter of a century since I’ve seen his hour-long Nice — À Propos de Jean Vigo (83), clearly meant as an homage to Vigo’s half-hour 1930 À Propos de Nice, but I remember thinking later how strangely sedate and polite it all seemed as a tribute to a fire-breathing anarchist. My favorite Oliveira features are his most transgressive, yet I also have to admit that part of what makes each of them qualify as avant-garde is the way these various transgressions rub shoulders with diverse forms of propriety and repression — the sort of traits that used to be called square. But then again, the ultimate avant-garde act may be to undermine what we mean by avant-garde.

I’ve seen 26 of Oliveira’s 29 features to date. One of those that I haven’t seen, Memories and Confessions (82), is, according to Oliveira’s own instructions, to be screened publicly only after his death. (I wonder if it constitutes, among other things, a political confession; it’s also said to be about a house he’s lived in for years.) His longest feature, the 400-minute The Satin Slipper (85), I’ve managed to see most of, but under uniquely frustrating circumstances: at an Oliveira event held at Brown University in 1998, repeated breakdowns in the projection of a 35mm print led to the entire audience being forced to leave well before the end in order to attend an already-scheduled panel discussion about the film — a perfect example of bureaucratic obtuseness at its most dysfunctional. The other missing item for me is Past and Present (71), Oliveira’s third feature — and this isn’t counting his 20-odd shorts and documentaries, only five of which I’ve seen.

As hazardous and provisional as such an undertaking might be, I’d like to rank all his other features in descending order of preference, in order to establish both where I’m coming from and, in terms of my own defense of his work, where I’m going. I’ve seen roughly half these films more than once, but my memories are more vague about many others, so the order assigned to the final 10 is somewhat more arbitrary:

1. Doomed Love (1978)

2. Benilde or the Virgin Mother (1975)

3. Inquietude (1998)

4. Porto of My Childhood (2001)

5. My Case (1986)

6. Francisca (1981)

7. I’m Going Home (2001)

8. Rite of Spring (1963)

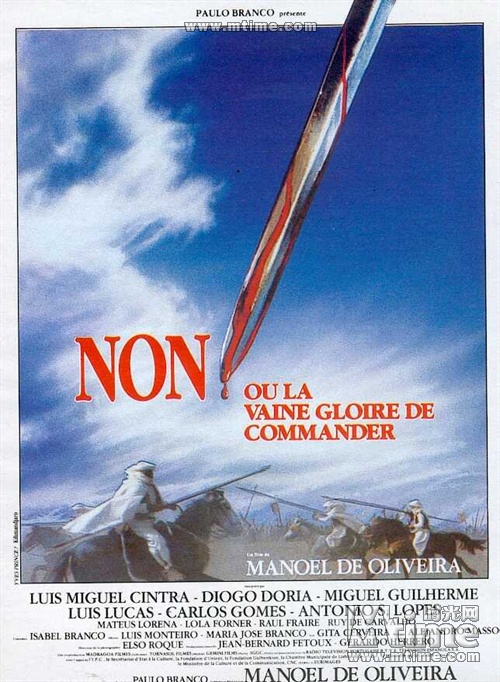

9. No, or the Vain Glory of Command (1990)

10. Day of Despair (1992)

11. Aniki-bóbó (1942)

12. Voyage to the Beginning of the World (1997)

13. Magic Mirror (2005)

14. The Letter (1999)

15. A Talking Picture (2003)

16. Belle Toujours (2006)

17. The Cannibals (1988)

18. The Uncertainty Principle (2002)

19. Valley of Abraham (1993)

20. A Caixa (The Box) (1994)

21. The Convent (1995)

22. Word and Utopia (2000)

23. The Fifth Empire (2004)

24. Party (1996)

25. Christopher Columbus, the Enigma (2007)

26. The Divine Comedy (1991)

A few general points about these assessments:

(1) As far as I’m concerned, there is no “golden age” in Oliveira’s career — even though what I take to be his supreme adaptations of prose fiction and theater, Doomed Love and Benilde, occur relatively early on, and the superb and pivotal modernist musical scores of João Paes, which play substantial roles in Oliveira’s films of the Seventies and Eighties, no longer figure in his work afterward. Nevertheless, masterpieces and less interesting or accomplished films turn up in all periods.

(2) Similarly, I can’t entirely privilege the films in Portuguese over the films in French, or the adaptations (which comprise most of his features) over the original scripts (such as Porto of My Childhood and No, or the Vain Glory of Command), or the adaptations of stories or novels over the adaptations of plays. In fact, two of Oliveira’s boldest and most original films, the Portuguese Inquietude and the French My Case, are derived from combining adaptations of theater with adaptations of fiction, while the no less adventurous Porto of My Childhood — an autobiographical documentary that could serve as an excellent introduction to Oliveira’s work if it were more readily available — freely draws on the resources of both theater and fiction.

My Case chiefly consists of three successive onstage adaptations of a frenetic 1957 one-act Portuguese farce translated into French, José Régio’s O Meu Caso, but it also manages to work in portions of Samuel Beckett’s Pour finir encore et autres foirades (a collection of stories known in the U.S. as Fizzles) and the Book of Job. Inquietude begins as another frenetic one-act Portuguese play (Helder Prista Monteiro’s 1968 The Immortals); it’s revealed to be a performance of the play taking place in Porto in the Thirties and attended by four characters adapted from António Patrício’s story “Suzy” (circa 1910). Then, one of these four characters in turn recounts to another the film’s third story, derived from Agustina Bessa-Luís’s haunting and magical 1971 fairy tale, The Mother of a River.

(3) While some commentators have tended to privilege the eight Oliveira features derived from or co-written by his novelist friend Bessa-Luís, I regard most of these as secondary, with the notable exceptions of Francisca and the third episode of Inquietude. Arguably no less important, and for me more interesting, is another writer friend of Oliveira’s, José Régio (1901–69), principally known as a poet, who wrote the plays Oliveira adapted in both Benilde and My Case as well as in The Divine Comedy (which also draws material from the Bible, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche, but perversely ignores Dante) and The Fifth Empire (El-Rei Sebastião, derived from Régio’s play, written only two years after Benilde). Although I’ve read nothing by either Bessa-Luís or Régio, I’ve mainly concluded, based on Oliveira’s adaptations, that Régio’s troubled existentialism and skepticism are far more fruitful and intriguing (at least from a dramatic standpoint) than Bessa-Luís’s congealed and conservative Jamesian ironies. But I also must confess that when I saw The Divine Comedy 17 years ago, I found it insufferably pretentious, hectoring, and dull; at their worst, Bessa-Luís’s stories seem boring and snooty, but I wouldn’t fault any of them for pretension or aggression. (Aggression, in fact, is what they sometimes appear to need the most. For me the most gratifying moment in Valley of Abraham occurs in the third hour, during a character’s interminable monologue about the decline of Western civilization, when another character suddenly lifts a purring cat from the heroine’s lap and flings it straight at the camera, as if to wake us all up.)

As suggested by the somewhat bewildering mix of materials in Inquietude that are drawn from 1910, 1968, and 1971, in a film set in the Thirties, the settings of Oliveira’s period films are sometimes difficult to date in relation to specific periods, apart from the specific periods of their major source materials (e.g., the late 16th and/or early 17th century for The Satin Slipper; the 17th century for Word and Utopia; and the 19th century for Doomed Love, Francisca, and the unjustly overlooked and underrated Day of Despair — the trilogy about novelist Camilo Castelo Branco). Along with such contemporary tales as I’m Going Home and Belle Toujours, The Letter provides a much clearer take on the 20th century than the eight films with Bessa-Luís, which for me often appear to exist in a kind of time warp arising from both the insularity and preciosity associated with wealth and the freezing of history typically found in totalitarian regimes.

(4) For a good many commentators, the 166-minute Francisca has eclipsed or supplanted the 262-minute, 16mm made-for-TV Doomed Love as Oliveira’s ultimate masterpiece about obsessive, unrequited love, perhaps to some extent because its distribution has been much wider. My preference for the earlier and longer film (explored in my criticism collection Placing Movies) has a lot to do with the evident superiority of its source material (widely regarded as one of the greatest of all Portuguese novels) and its exceptional theoretical interest as a workshop of ideas regarding cinematic literary adaptation — rivaled to my mind only by Greed. It’s a tribute to the epic staying power of Doomed Love that it survived even a recent showing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music that denied it an intermission, omitting an important element in its dramatic structure.

(5) The strident, over-the-top acting featured in My Case and in the production of The Immortals in Inquietude is in striking contrast to the distanciated underplaying more characteristic of Oliveira’s other films, which sometimes come across more as “representations” than as performances (especially in Doomed Love, Francisca, and The Satin Slipper). And for me, the most impressively acted of the films lying between these extremes is Benilde, which also boasts the most astonishing opening shot to be found in any Oliveira film.

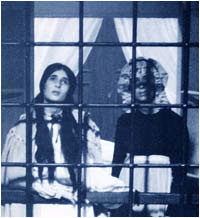

Like the original opening of Touch of Evil, this shot appears behind the credits — with Paes’s bombastic, apocalyptic score, punctuated by manic screams and moans, accompanying a rapid, endless tracking shot that snakes and pans around the labyrinthine backstage spaces of Lisbon’s Tobis Studios until it finally arrives at and enters the film’s set, a room in the mansion where the play takes place. Then, as in Michael Snow’s Wavelength, the camera continues its journey all the way up to a framed photograph on a wall, in this case depicting a field, at which point the following title is superimposed: “The action of this film is supposed to take place in the 1930s.”

The wickedly and subtly subversive “supposed to” introduces a note of existential doubt that’s in fact central to Benilde — a film that indelibly captures the dread of living under totalitarian rule by following the same general approach adopted for Vichy France in Clouzot’s 1943 Le Corbeau and for Franco’s Spain in Bardem’s 1956 Calle Major: reformulating political oppression in sexual terms. The 18-year-old title heroine, living sequestered with her widowed father and a maid, has become pregnant, and since she’s an avowed virgin, she claims it’s an Immaculate Conception. But she also sleepwalks, while some of the other characters think that a crazed village outcast is somehow to blame. The remainder of the three-act play steadfastly refuses to confirm or refute either explanation. The remote setting, the spiritual ambiguity, the competing interpretations, the lighting and the mise en scène — all recall Ordet without the closing miracle. Instead, at the end we get a shortened and slowed-down reversal of the opening shot, making Benilde as much a theoretical statement about filmed theater as Doomed Love is about filmed literature.

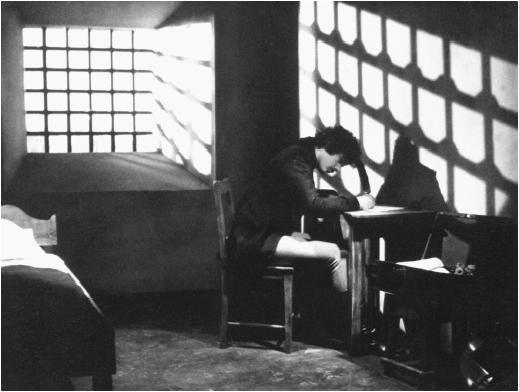

But this shouldn’t imply that either masterpiece is any sort of formalist exercise; both are also claustrophobic hothouses of fierce meditation about ideological and spiritual as well as physical confinement. Benilde is a suffocating chamber piece, while Doomed Love, which opens with an iron gate swinging shut, emphasizes the bars in convent and prison alike. (The latter, incidentally, was inspired in part by a viewing of Straub-Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach — as we learn from Conversations avec Manoel de Oliveira, by Antoine de Baecque and Jacques Parsi, the best of the French books devoted to his work.)

Superficially, Benilde might be said to bear some thematic relationship to Magic Mirror (05), made 30 years later, about a wealthy woman (Leonor Silveira) determined to witness an apparition of the Virgin Mary. But in fact I’m more apt to view it in terms of contrast, offering another illustration of the arguable superiority of Régio’s existential skepticism over Bessa-Luís’s more conservative wit and irony. (More mannerist than Doomed Love, Francisca for me periodically founders on its surfeit of hollow and posturing banter, its silly aphorisms such as “Death is only a moral accident” and “If fatality was a woman, I would marry her.”)

The grandest claims to have been made for Oliveira, and in some respects the most persuasive, are those suggested by Raymond Bellour, in 1997. Bellour associates Oliveira’s name with the word “civilization” (“a word far greater than cinema, its life or death”), and continues, “Oliveira’s preoccupation is, to put it banally, the fate of the world, how to live and die, survive in harmony with the logic of an ancient and prestigious country, which was fortunate to discover the world when it was worth discovering, and the strange destiny of having in part escaped the worst conflicts of this century thanks to a cruel and miserable dictatorship. He is, I believe, the only filmmaker who knew how to tell, in a single film, the history of his country, from its founding through a melancholy myth up to the end of its empire (No, or the Vain Glory of Command).”

This accounts for the difficulty of Oliveira’s cinema as well as its importance and necessity — especially during a period when the fate of the world has been widely perceived to be a less pressing matter than the accumulation of wealth by a few individuals whose lack of interest in art is as conspicuous as their obsession with empire. As we return to what Eric Hobsbawm in my opening quote has described as barbarism from a 19th-century perspective, the civilized serenity of a broader view is bound to seem somewhat remote.

The author thanks Scott Foundas and Richard Peña.

© 2008 by Jonathan Rosenbaum