Tracy Young, my editor at Soho News in 1980-81, accorded me an unusual amount of freedom and a minimum of editing (which often amounted to the same thing), but she didn’t allow me to publish this article, written in July 1981. She approved it in principle when I proposed it, then refused it after it was written — the first and only time this happened during my year and a half on this weekly paper, where I was working as both a film and book reviewer. Later on, she wound up ripping out (or, in capitalist terms, salvaging) the reviews of Zorro, the Gay Blade and Heart to Heart, and running them on August 4, 1981 with Seth Cagin’s review of Victory, under the title “Transcendental Cuisine,” without explanation.

At the suggestion of Straub and Huillet themselves, this article was later included in a 20-page tabloid-size publication that I edited about their work to accompany the first (and, I believe, to date, only) full U.S. retrospective of their work, which I curated, at the Public Theater in New York, from November 2-14, 1982, which also included ten programs consisting of films by others that they selected to run with their own work, ranging from Blind Husbands to Antonio das Mortes to A King in New York to Civil War (the John Ford episode in How the West Was Won, shown with A Corner in Wheat and Land without Bread), and including several appearances by and discussions with Straub and Huillet. Recently, on his blog Kinoslang, Andy Rector reprinted another article in this publication that was selected by Straub and Huillet, Luc Moullet’s “Film is Only a Reflection of the Class Struggle” (translated into English by Sandy Flitterman).

When I decided to include this piece in my subsequent book Film: The Front Line 1983, my editor at Arden Press insisted on deleting the reviews of Zorro, the Gay Blade and Heart to Heart, exercising a kind of censorship that curiously paralleled that of Tracy Young at the Soho News. — J.R.

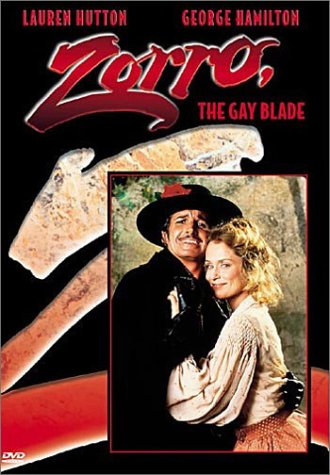

Zorro, the Gay Blade

Written by Hal Dressner

Directed by Peter Medak

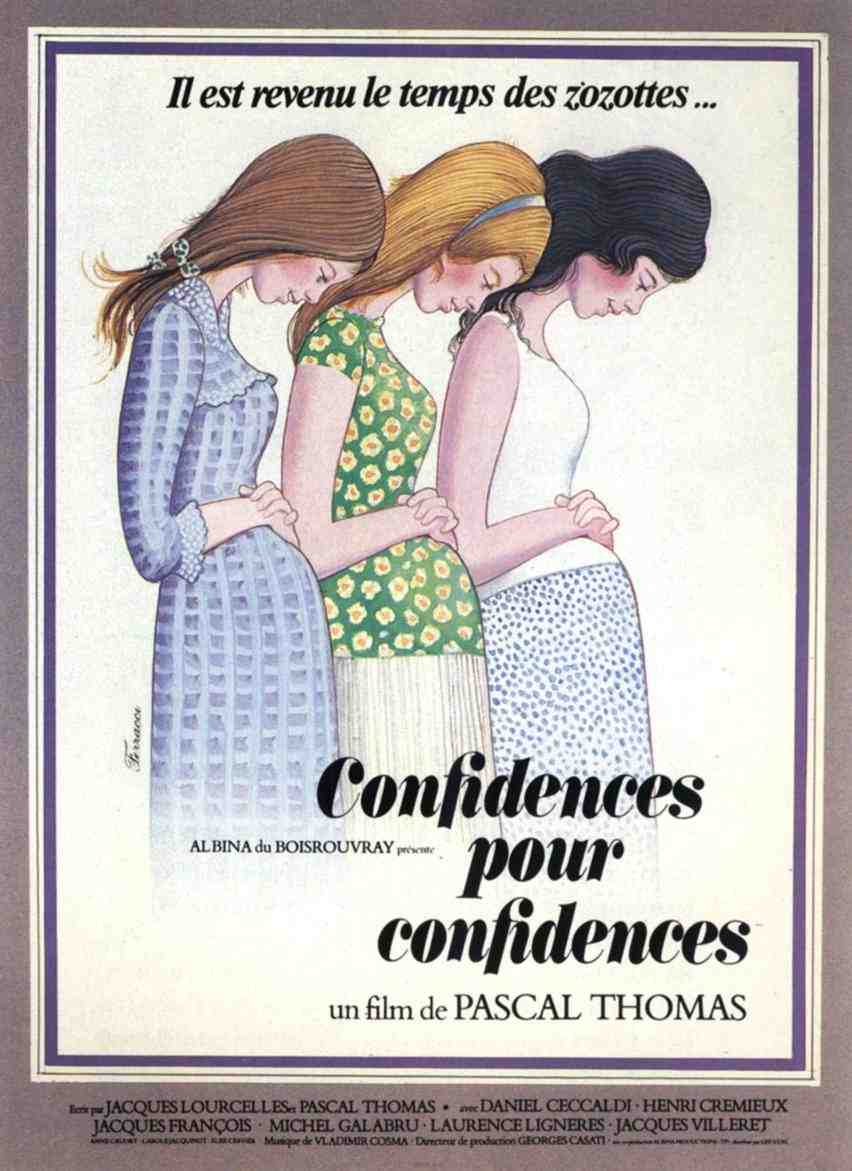

Heart to Heart (Confidences pour Confidences)

Written by Jacques Lourcelles and Pascal Thomas

Directed by Pascal Thomas

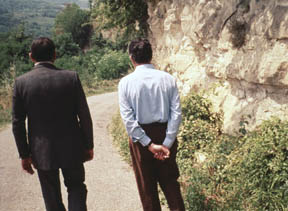

From the Cloud to the Resistance (Dalla Nuna resistenza)

Text by Cesare Pavese (from Dialogues with Leuco, 1947, and The Moon and the Bonfires, 1950)

A film by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet

In a characteristically gross and funny episode about a haute cuisine establishment in William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, we’re told at one point that “Robert’s brother Paul emerges from retirement in a local nut house and takes over the restaurant to dispense something he calls the ‘Transcendental Cuisine’…Imperceptibly the quality of the food declines until he is serving literal garbage, the clients being too intimidated by the reputation of Chez Robert to protest.”

It’s a passage that often comes grimly to mind when I contemplate The Art of Movies as it’s officially defined in our Transcendental Culture. But insofar as the analogy with film actually holds, I’m afraid that things are even worse off in my profession than in Burroughs’ Swiftian nightmare. At least the clientele of Chez Robert smells or suspects the presence of something rotten, while by and large the possibility that we’re all consuming literal garbage seems less likely to cross the standard film buff’s mind. Worse still, the possibility that better fare actually exists somewhere, even though it rarely finds it way to our plates, seems scarcely to have occurred to most moviegoers. They certainly haven’t been helped or guided much in this process by critics, whose professional loyalty seems to belong more to the garbage merchants (who treat them to free meals) than to their fellow hapless consumers.

I’m one of those garbage freeloaders and consumer guides too, even though every once in a blue moon a real movie comes along, something capable of changing my life, and it makes me gag a little on the others. I even have trouble holding the real movie down as a total entity, especially at first, because it’s generally too much for me. I have to break it down into manageable units first, and I only get bits and pieces; friends, critics, and cohorts help me find others; still other parts slide perpetually out of grasp, remain elusive. I’m the reverse of that critic on a rival weekly [Andrew Sarris] — the one who just referred to me, flatteringly, as “Some of the people who have written recently on Juke Girl”– who categorically states, “I cannot even begin to evaluate a movie unless I have seen it from beginning to end.”

It’s a reasonable-sounding statement, but one predicated on closure – the kind of movie which doesn’t change your life much except by extending it a little, which is the kind we both usually get paid to promote. He clearly isn’t talking about Snow’s Le Région Centrale or Tati’s Playtime or Godard and Miéville’s Numéro Deux or Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s From the Cloud to the Resistance, which are too radical as movies to begin or end in the ordinary sense. The latter film began for me weeks ago, when I booked the film for my Seminar in Current Cinema at NYU, continued when I checked out translations of the two Pavese books it uses from a library, was overturned when I saw it with students and friends last week, and is still in dazzling progress. Playtime hasn’t end yet, either; to evaluate it, one has to look at a lot more than other movies.

From the Cloud to the Resistance: an interesting, descriptive title that lucidly traces a passage between the two mythological and political possibilities of film itself — from the idealism of the medium, where stars are like gods in the sky and transcendental fiction is bigger than life (Part I — Pavese’s 27 poetic, difficult 1947 dialogues between gods and mortals, six of which are used in the film) to the material resistance of the earth and human and animal life to aggression and oppression imposed from above (Part II — Pavese’s last book before his suicide in 1950, a novel about the Italian resistance against Mussolini). Common to both parts is the same lush, brightly lit countryside and Pavesean imagery: blood, stone, trees, moon, bonfires, fields.

It should be stressed that this beautiful, intractable, 1979 Cézanne-like landscape film is being distributed non-theatrically in the U.S. by New Yorker Films, and is not going to open here, perhaps not ever. Straub and Huillet are major European filmmakers, but ever since their Moses and Aaron showed at the New York Film Festival in 1975, and was reviewed in the New York Times as Aaron and Moses (a title Vincent Canby persists in getting wrong even today), their subsequent films — one short and two features — have been almost totally ignored in this country, and will continue to be. From the Cloud to the Resistance, one of their very best, hasn’t a ghost of a chance of opening here.

The incapacity of New York to deal with it on any level is neither surprising nor unprecedented, given the personal stake we all have in keeping up the garbage flow (our Transcendental Cuisine) and shunning the very possibility of a movie that requires a certain kind of work and engagement. For one thing, it forestalls the convenient digestibility of a beginning and end that clearly separates it from life….But let me turn first to my professional duties.

***

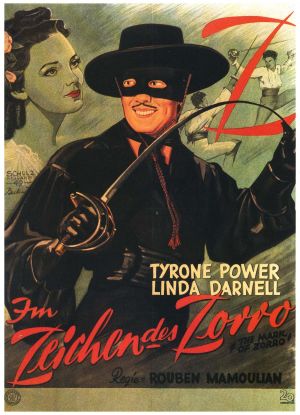

Zorro, the Gay Blade is dedicated to Rouben Mamoulian — director of The Mark of Zorro (1940), which this mainly lame parody is loosely patterned after — “and the other great filmmakers whose past gave us our future.” Grim words, but it’s important to remember that garbage likes to stay contextual and pattern itself after other garbage. So we start off with a nostalgic black and white clip of the original Big Z, before the movie obligingly moves on to other spinoffs and replays. I haven’t seen Love at First Bite, the previous George Hamilton genre spoof, but when I hear Hamilton’s clotted Spanish accent saying “ship” for “sheep” of waffling on about his desire to fight for the downtrodden “pipples,” I’m immediately brought back to the Gallic verbal fractures of Peter Sellers’ Inspector Clouseau. (Later on, Lauren Hutton has a sexy way of teaching him how to say “vulnerable”.)

There are plenty of more chances here to remember other garbage. The shrill stridency of Rob Liebman as the villain evokes Richard Mulligan in S.O.B. Fans of Brenda Vaccaro’s TV ads for Playtex tampons who were chagrined to find her wheezy intakes of breath removed from the soundtrack after a spell will be gratified to discover that her gaspy punctuations are retained here. Director Peter Medak usually has a nice sense of when to cut to high-angle interior setups that, if I recall correctly, also served him well on The Ruling Class in 1972. (This is of course only an interim report that may ultimately change in relation to the cosmic long view of international film history; clearly I’d have to see The Ruling Class again from beginning to end before I could make a measured judgment on this matter.)

To make another tentative evaluation: A teenager looking for a dumb action matinee farce could probably do worse or better than Zorro, the Gay Blade. He or she might find Hamilton tolerable as Don Diega Vega and bloody awful as his gay English-bred twin brother Bunny Wigglesworth, who incidentally figures in this “swishbuckler” as the least convincing transvestite since the horse in Disney’s Icabod and Mr. Toad. Personally, I would have preferred the more dapper, equally self-ingratiated Peter Bogdanovich giving his all to both parts.

***

Heart to Heart — yet another French nostalgia movie about female adolescence, made in 1978 — seems designed to warm the innards of the sort of gooey, xenophobic garbage critics who think that Alain Resnais is a heartless structuralist. Just think of the emotional impact of a movie beginning and ending with a freeze-frame, whose narration starts with a female voice saying, “I feel sad — I want to tell the story of my family.” Before long, one can hear “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing” being sung in French in a snow-covered courtyard that’s grey rétro-style, and then see cozily lit family interiors, nicely shot by Renan Pollès, that resembles old full-color ads in Collier’s. Around that same period, movies like Heart to Heart were already being made — starring actresses like Doris Day, Linda Darnell, and Jean Peters, and usually set 30 years or more before the present — only this is French transcendental cuisine for Yankee export, higher grade stuff, which means Hollywood without the Hays office and production code.

Jacques Lourcelles, an intelligent film critic who has written a book on Otto Preminger and translated novels by Samuel Fuller — one of the French generals in The Big Red One is named after him — collaborated with Pascal Thomas on the script, which is serviceable fluff about three daughters growing up. A few teenagers, both young and old, may get a few good cries and chuckles out of this; I was mainly bored by the movie’s efforts to dish out endless quantities of goodwill, like a Truffaut vending machine that has somehow gone berserk.

***

According to an Italian anthropologist who visited my class, From the Cloud to the Resistance is post-Pasolini in relation to linguistics. (The relevance of Straub-Huillet to Pasolini and vice versa is problematic but unavoidable, because the issues of translation on multiple levels and a Marxist, dialectical delation between antiquity and the present seems central to both.) Part I features formalized deliveries of a wide variety of regional peasant dialects, while in Part II the non-professionals speak in a local dialect of Piedmont, the northern region where the action is set.

One of the most remarkable sequences in Part I is a dialogue between Oedipus and Teresias shortly before the former’s misfortunes begin. The camera is stationed directly behind them on a wagon drawn by oxen that’s being pulled along a lovely country road by a male peasant. The peasant is never mentioned or acknowledged once by either speaker, yet he’s the constant, bobbing center of all the long takes recording the dialogue and its silent aftermath — the precise equivalent of the offscreen cameraperson behind the speakers (another ignored worker setting the whole show in motion), who are conversing mainly about sex and blindness, and there’s a stunning moment at the end of the conversation when Oedipus prays to God that he won’t become blind, just as a beautiful clump of red flowers –rhyming with a red toga over Teresias’ left shoulder — appears on the right side of the road. Earlier, their discussion of sex occurs under dark tree branches punctuated by flickers of light, before returning to a bright patch of road that, as critic Gilberto Perez points out to me, traces a full circle.

Perez — whose essay, “Modernist Cinema: The History Lessons of Straub and Huillet” in the October 1978 Artforum [2010 note: see his terrific book The Material Ghostfor a modified version of this] is an invaluable guide to their work — informs me that the long car ride through Rome in their History Lessons (1972), a clear forerunner of this gorgeous sequence, is also circular, and notes that the rear-view mirror at screen center framing the driver’s eyes offers a parallel to the peasant/camera dichotomy. Offsetting one thing with another — including the visible with the non-visible — is basic to Straub-Huillet’s strategies. And I like what another critic, Serge Daney, says about material resistance itself being a constant theme of their work — the resistance of texts to bodies, of locations to texts, of bodies to locations. (This is already implicit in the very title of their first feature, in 1965, Not Reconciled.)

Straub-Huillet seem to identify with only two characters in their new movie — a baby wolf* in Part I who appears to be dying (occasioning a dialogue between the two hunters about the man, Lycaon, he once was before Zeus punished him) and a little boy who survives the death of his family in Part II. The monumentality of their best compositions is like the obstinate will that has enabled them to raise money and produce all 11 of their beautiful, impossible films –as hard and as angry as granite, as implacable as Fritz Lang or Carl Dreyer or Kenji Mizoguchi, often brutally thwarting our desires (such as holding the most handsomely framed and colored interior shot in the movie — a summary of eight rugged anti-partisans standing at a bar, singled out in preceding shots — for scarcely an instant, so that it hits you like a brick.) Yet the tenderness of their work perhaps places it within the termite range, as coined by Manny Farber, and outside the whole bluff of White Elephant Art.

The weather was beautiful in washington Square Park before and after I saw From the Cloud to the Resistance; the movie didn’t make it that way. but it made me see, hear, and feel more of it. According to the present state of received ideas, the right-wing formalism of Carpenter, De Palma, and Lucas-Spielberg is “good clean fun,” not politics or ideology, wile the left-wing formalism of Godard or Straub-Huillet is supposed to be pleasureless politics, no fun at all — torture to critics who hate to think too much, hence impossible for most of us to see.

***

But the talent of the good-clean-fun guys mainly has to do with their capacity to make me either forget or enjoy the fact that they’re shoveling garbage. They haven’t got anything to say to me about the weather outside. And the absence of Straub-Huillet and other exemplary termites here has also meant the absence of what might have produced some thrilling criticism. The silence of Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson for the past four years as film critics (their last published article, significantly, was on another [then-] undistributed masterwork of the 70s, Jeanne Dielman) can probably be explained in part by the quarantine placed on the kind of movies they appreciate and support the most — a quarantine collectively maintained by a community of “scholars” who despise the possibility of having to think too hard.

“For all their usefulness, termites can never be entombed in the Pantheon,” a local and celebrated garbage collector [Sarris again] recently had the considered loftiness to announce. No, thank God, but at least they can eat away at the crumbling pillars supporting that Pantheon — which may prove to be more useful in the long run. Who wants to be entombed, anyway, except for people who are already dead? Next to that transcendental version of Forest Lawn, I’ll take Straub-Huillet’s material resistance in a flash. The fact that most us are unable to see it is our problem, not theirs — White Elephant criticism (which is all we have, alas), not Termite Art.

Note

*”The only small mistake of your article: it is not a ‘baby’ wolf, but an adult normal one — coming from the Abruzzi — ; it was the rock, the stone, which was very big…” (From a letter by Danièle Huillet to author, 18 May 1982).