Here are ten of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1995 / The Neon Bible – “It didn’t snow that year.”

U.K. (Academy/Channel Four). Director: Terence Davies.

Cast: Drake Bell, Jacob Tierney, Gena Rowlands.

Why It’s Key: It reveals the power of imagination in a flash.

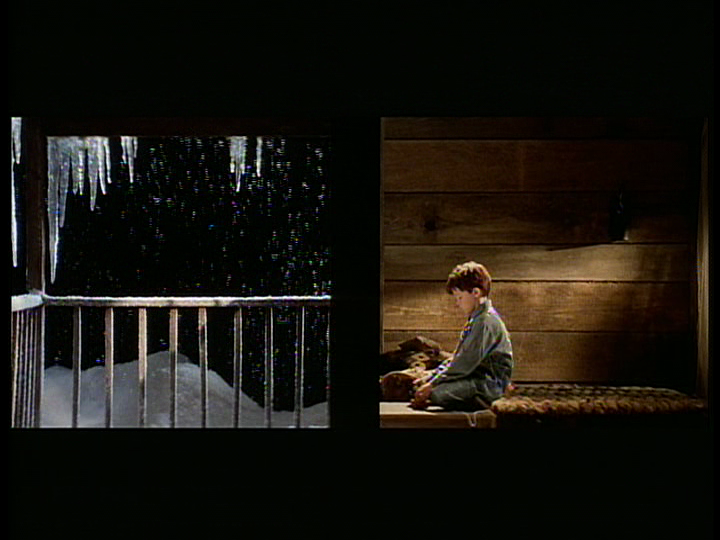

Few moments in movies reveal the power of imagination more succinctly than the opening of Terence Davies’ CinemaScope adaptation of John Kennedy Toole’s first novel, written when the southern author was only 16. It opens with 15-year-old David (Jacob Tierney) alone on a train at night, the camera moving past him to the darkness glimpsed outside. Then David at ten (Drake Bell) is seen peering out a rain-streaked window in his rural home to the strains of “Perfidia”, circa 1948, while narrating offscreen, “People came to see us that Christmas. They were nas, those people —- they brought me things…”

A moment later, we cut to a diptych: on screen left, an empty porch topped by icicles framing an enchanted snowfall, as decorous as a neatly filled box by the surrealist artist Joseph Cornell. On screen right, young David is seated on the floor inside, now looking out the same window in profile, while narrating offscreen, “There was no snow —- no, not that year.” When the next shot shows us his aunt (Gena Rowlands) in full frame greeting him through the window, the icicles are still lining the top of the frame. But a shot later, when David comes out on the porch to greet her, it’s raining again.

Davies, who once compared filling a CinemaScope frame to settling down in Canada, also knows the period like the back of his hand. And the power of snow to briefly supplant rain in a ten-year-old’s mind has the force of an epiphany.

***

Scene

1919 / Tih Minh – Sequestered society women break free from their captivity in a villa and run amok in a garden.

France (Gaumont). Director: Louis Feuillade. Cast: uncredited.

Why It’s Key: Pre-Surrealist visual poetry about respectable perversity and lyrical hysteria.

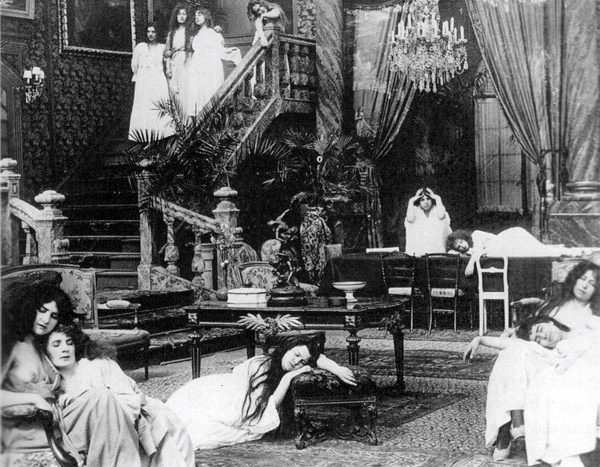

Think about a dozen or so ladies in the respectable society of the Côte d’Azur, clad in white. They’ve all been kidnapped and drugged senseless by a band of nefarious villains, who sequester them in Nice’s opulent Villa Lucile, which is bugged with hidden microphones. Suddenly, the women break free from their captivity and run outdoors, into the warm Mediterranean sunlight. Imagine them fluttering around a formal garden like butterflies or drifting handkerchiefs as they suddenly taste and enjoy their freedom.

Better yet, don’t think at all, but dream a little instead. It’s hard to believe that Louis Feuillade and his resourceful cast and crew were doing anything but playing out giddy fantasies of their own, never mind what they meant. Tih Minh (1919) isn’t the most celebrated of the wonderful Feuillade serials, each of which run between five and seven hours. Fantômas (1914), Les Vampires (1916) and Judex (1917), all released by now on DVD, are better known. But Tih Minh, as Gilbert Adair points out, is undoubtedly “the greatest, which is to say, the weirdest, most uncanny, most dreamlike.”

What’s it about? The title heroine is the Vietnamese fiancée of adventurer Jacques d’Athys, who, on a mission in India, comes into possession of a sacred book containing the secret of a fabulous treasure. The three scheming villains kidnap the fiancée and drug her into amnesia in order to persuade d’Athys to relinquish the book, and those society women are likewise victims of the same criminal modus operendi.

***

Scene

1967 / 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her – A cup of coffee becomes the cosmos.

France (Anouchka Films/Argos Films/Les Films du Carrosse/Parc Film). Director: Jean-Luc Godard. Cast: Marina Vlady. Original title: 2 ou 2 Choses que je sais d’elle.

Why It’s Key: Godard finds the universe in a grain of sand -– or, more precisely, in a cup of coffee and a sugar cube.

In some ways, 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her is the color and ‘Scope climax of Godard’s “research” before 1968, and its personal importance can be felt in how he narrates the film in a kind of urgent whisper. Following the day in the life of Juliette (Marina Vlady), a suburban housewife who works part-time as a prostitute in order to buy clothes, he follows her into a Paris café, where she drinks a Coke. Then he cuts to other people and objects in her immediate vicinity while delivering a poetic monologue about his difficulties in coming to terms with the modern world. Midway through his rap, he settles on a gigantic close-up of a cup of coffee.

Between pauses and cutaways, he ponders the swirling black liquid as if it were the solar system, turning metaphysical: “Since I can’t extricate myself from the objectivity that crushes me or the subjectivity that isolates me, I have to listen, I have to look around myself more than ever. The world —- mon semblable, mon frère.” He cuts to closer and closer views of the coffee as a sugar cube drops in and dissolves: “The world alone today, where revolutions are impossible, where bloody wars menace me, where capitalism is no longer sure of its rights and the working class is in retreat, where the overwhelming progress of science gives future centuries an oppressive presence, where the future is more present than the present, where far-off galaxies are at my door…mon semblable, mon frère.”

***

Film

1998 / Histoire(s) du Cinéma – Godard’s Tribute to Italian Neorealism.

France (Gaumont). Director: Jean-Luc Godard. Cast: uncredited.

Why It’s Key: The major thinker of the French New Wave shows that he also has a heart.

Godard’s magnum opus to date, at least of his late period, is an eight-part video, though film is its main subject —- a critical reverie comprised of multiple clips, commentary, and many general allusions to art and history. More precisely, it’s the history of the 20th century as perceived by cinema, and the history of cinema as perceived or at least witnessed by the 20th century. In terms of Godard’s adopted mythology, moreover, the cinema and the 20th century are characterized by two key countries (France and the U.S.), two decisive falls from cinematic innocence (the end of silent films that came with talkies and the presumed end of talkies that came with video), two decisive falls from worldy innocence (the two world wars), and two collective cinematic resurgences that took place in Europe, affecting the consciousness of the rest of the world—-Italian neorealism and the French New Wave.

For me, the work’s climax comes at the end of the fifth episode, Currency of the Absolute, when Godard accompanies a passionate montage of emotional highpoints from Italian neorealist films with a tender Italian song about the Italian language. There’s a Godardian theory behind this, of course, involving his conviction that « with Rome, Open City, Italy simply reconquered the right of a nation to look itself in the eye, and there followed the astonishing harvest of great Italian cinema. » But whatever the occasion or pretext, the outpouring of pure emotion at the end of this chapter has few precedents in his work.

***

Scene

1964 / I am Cuba – Crazed Formalist Propaganda.

Soviet Union/Cuba (Goskino/ICAIC). Director: Mikhail Kalatozov. Cast: uncredited. Original titles: /Soy Cuba/Ya Kuba.

Why It’s Key: One of the most spectacular camera movements in the history of cinema transcends its apparent motivation.

This misguided yet awesome Soviet-Cuban tribute to the Cuban Revolution, comparable in some ways to the Latin American adventures of Sergei Eisenstein (the unfinished Que Viva Mexico!) and Orson Welles (the unfinished It’s All True), contains many awesome stretches of virtuoso filmmaking from cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky.

Among the more spectacular instances of camera movement is a delirious, breathtaking two-and-a-half minute shot. Like an earlier shot that moves several floors down a hotel exterior to approach and enter a swimming pool before going underwater, it’s a kind of shot that only could have been realized through teamwork and a relay of camera operators —- collective artistry in action.

The coffin of a radical student slain by Batista’s police during a mass uprising is carried by his comrades through downtown Havana, surrounded by a huge crowd. The camera moves ahead of a young woman and past a young man–catching him in close-up as he turns around, hoists the front of the coffin onto his right shoulder, and walks away with the other pallbearers — then cranes up the five floors of a building, past people watching from balconies and parapets. The camera moves to the right across the street and through a window into a cigar-rolling factory, where it follows workers as they hand a Cuban flag one to another, eventually unfurling it from a window. The camera moves out that window and over the flag, then follows the funeral cortege from above for what seems like a quarter of a mile.

***

Scene

1999 / The Wind Will Carry Us – The hero asks his boy guide whether he thinks he’s a bad man.

Iran/France (MK2 Productions). Director: Abbas Kiarostami.

Cast: Bezhad Dorani, Farzad Sohrabi. Original title: Bad ma ra khahad bord.

Why It’s Key: Kiarostami exposes what’s questionable about his own tactics as a filmmaker.

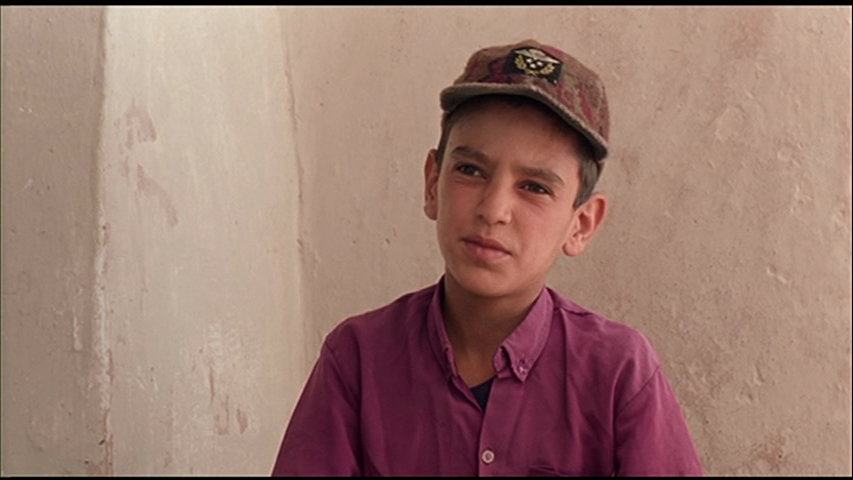

An engineer named Behzad (Behzad Dorani) arrives with a small camera crew in a very remote Kurdish village, waiting for a one-hundred-year-old woman to die so he can shoot a documentary about the funeral ceremony. (Coincidentally or not, this 1999 film qualifies as a sort of millennial statement in more ways than one.) A local boy named Farzad Sohrabi serves as his guide, and Behzad often exploits and abuses him shamefully, especially when he’s frustrated about the old woman not dying quickly enough.

Behzad is plainly Kiarostami’s critical self-portrait — a skeptical look at the kind of power he wields over the non-professional and poor actors he often works with. And he proves how skeptical he is in the way he films some of the dialogues between Behzad and Farzad, firing his own questions at the boy and then subsequently intercutting his responses with shots of Behzad that were filmed later. In one of the most telling of these exchanges, Behzad asks the boy to tell him frankly, “Do you think I’m bad?” The boy blushes as he says no, and one has the impression that he’s simply being polite.

Kiarostami confirmed this impression when I asked him about it in an interview: “I had to ask him that question because he didn’t like me very much, in contrast to the actor who was playing the main character,” he said, laughing. “So that’s why he wasn’t very convincing when he called me a good man!”

***

1987 / Full Metal Jacket – The closeup of a dying Vietcong woman, a sniper.

U.S. (Warner Bros. Pictures). Director: Stanley Kubrick.

Cast: Matthew Modine, Ngoc Le.

Why It’s Key: It condenses the film’s power into an intense, mysterious moment.

I had the rare privilege of seeing Stanley Kubrick’s last war picture — an adaptation of Gustav Hasford novel’s The Short Timers, about his experiences during the war in Vietnam — with war specialist Samuel Fuller, shortly after the film came out. He didn’t much care for the picture, he said afterwards, because he didn’t much like films about training, and besides, this movie wasn’t antiwar enough for his taste; he thought it might even encourage some teenage boys to enlist in future wars. Of course, Fuller had extensive war experience and Kubrick had none, which might have also played some role in forming his bias.

But one thing in the film that he loved without qualification was the close-up of the wounded Vietcong sniper at the end while she’s begging for Joker (Matthew Modine) to finish her off —- above all, for the look of absolute hatred in her eyes. “How did Kubrick do that?” he said with admiration.

It’s a powerful scene in many ways. For one thing, it’s a moment when the Feminine Other that’s been haunting all the grunts throughout the picture is finally confronted head-on —- an obsession that comes to the fore repeatedly in the opening sequence in training camp. It also creates a truly upsetting rhyme effect with the closeup of the insanely grinning “Gomer Pyle” just before he shoots Sgt. Hartman at the end of that opening sequence — a rhyme conveyed almost subliminally through a hum on the soundtrack over both close-ups.

***

Scene

2003 / Down with Love – concluding musical number.

U.S./Germany (Fox 2000/Mediastream Dritte Film GmBh & Co.).

Director: Peyton Reed. Cast: Renée Zellweger, Ewan McGregor.

Why It’s Key: Maybe it gets the early 60s wrong, but it gets 2003 exactly right.

Down with Love tries to spoof three comedies I couldn’t care less about — Pillow Talk (1959), Lover Come Back (1961), and Send Me No Flowers (1964). I’m delighted that the filmmakers, too young to have experienced this era first-hand, got it all wrong, from studio logo to palatial Manhattan penthouse apartments (as in How to Marry a Millionaire and The Tender Trap) to “think-pink” advertising décor (as in Funny Face and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?), all of which date from 1953-1957. And the visual and verbal double entendres, antismoking gags, and overt references to feminism and homosexuality, no matter how hilarious, all clearly come from post-1964.

But this collapsing of the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s into a hyperbolic dream of a dream speaks volumes about who we are today, expressing a yearning for what’s wrongly perceived as a less cynical and more innocently romantic period. Preoccupied with a trio of hypocritical comedies as if they contained awesome and precious secrets, Down With Love offers a surprising number of creative and poetic insights into some of the more tender aspirations of today.

The payoff is the wonderfully executed and exuberant concluding musical number, “Here’s to Love,” where Renée Zellweger and Ewan McGregor, the two stars in evening drag, bump and grind their way through lurid colors and tacky TV set designs as if they were frolicking through some version of paradise regained. However ironically pitched, their euphoria seems genuine enough to renew one’s faith in the possibility of a reinvented present.

***

Film

1959 / Hiroshima mon amour – The twitching hand of a lover.

France/Japan (Argos Films/Como Films/Daiei/Pathé).

Director: Alain Resnais. Cast: Emmanuelle Riva, Eiji Okada.

Why It’s Key: It’s probably the first Proustian shock cut in cinema.

It’s almost 20 minutes into Alain Resnais’ mesmerizing first feature (1959), after an extended depiction of a night of lovemaking and conversation between a French film actress and a Japanese architect, both married to other people, who’ve just met in contemporary Hiroshima. Their night is conveyed impressionistically, unfolding like a piece of music. She describes her visit to the Peace Museum, which documents in excruciating detail the effects of the Atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and he replies, “You know nothing of Hiroshima.” We discover that she lives in Paris, and before that lived in Nevers, but we still know nothing about her past there.

In the morning, dressed in a kimono and holding a cup of tea or coffee, she stands on a broad terrace, looking down at bicyclists far below, then returns to the bedroom where her lover still lies sleeping, his outstretched right hand twitching slightly. There’s a sudden cut to a close-up of the twitching hand of her dying German lover in Nevers almost 15 years earlier, the camera quickly panning up to his blood-streaked face as she kisses him, although at this point we don’t know who he is or where they are or anything else about them apart from the jolt of this traumatic moment. This may be the first such “subliminal” flashback in film history, a shock cut rendering an involuntary memory-flash of Proustian intensity, and much of the remainder of this remarkable feature will be devoted to unpacking it.

***

Scene

1962 / Cleo from 5 to 7 –– Cleo sings a song.

France/Italy (Ciné Tamiris/Rome Paris Film). Director: Agnes Varda. Cast: Corinne Marchand, Michel Legrand, Serge Korber. Original title: Cléo de 5 à 7.

Why It’s Key: All of a sudden, the title heroine sees her life anew, and the film changes key.

Cleo from 5 to 7 supposedly charts the two hours during which the title heroine (Corinne Marchand), a pop singer, waits to learn if she has terminal cancer. But it’s characteristic of Varda’s playful shifts between objectivity and subjectivity that the film only lasts 90 minutes. Despite chapter headings that claim almost scientific precision (“Chapter VII, Cleo from 5:38 to 5:45 pm”), there are plenty of ruses for changing the registers of reality, sometimes even in the middle of shots.

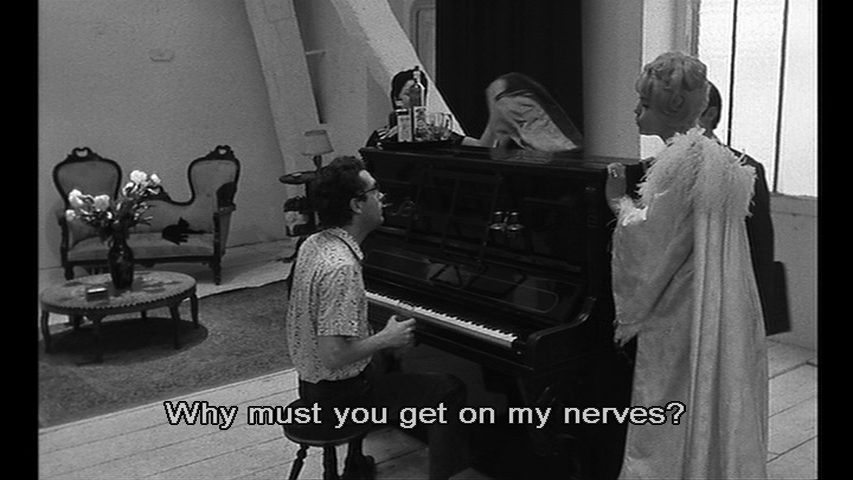

The preceding chapter, “Bob from 5:31 to 5:38,” half an hour into the film, charted the arrival at her Paris digs of her pianist-composer Bob (played by Michel Legrand, the film’s pianist-composer) and lyricist (Serge Korber). They carry on like clowns while running through a lovely repertory of possible songs for her —- including a catchy waltz in which Varda’s camera keeps time by swinging back and forth between the characters. Then Chapter VII ushers in “Sans toi,” a tragic torch song Cleo sings with sheet music while the camera slowly traces a crescent shape around her. But midway through the shot, the piano’s replaced by an unseen orchestra, the lighting shifts to theatrical, and she’s no longer reading the lyrics. By the time the song’s over, Cleo’s mood has darkened considerably, and she promptly shifts her wardrobe from white to black and sheds her wig. According to Varda, this sequence is “the hinge of the story,” and “the circular movement which isolates Cleo is like a huge wave carrying her off.”