This review appeared in the January 1977 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. The American title of this film was Jailbait.– J.R.

Wildwechsel (Wild Game)

West Germany, 1972

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Cert — X. dist –- Contemporary. p.c –- InterTel (West German TV). In collaboration with Sender Freies. p — Gerhard Freund. p. sup -– Manfred Kortowski. p. manager -– Rudolf Gürlich, Siegfried B. Glökler. asst. d –- Irm Hermann. sc –- Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Based on the play by Franz-Xaver Kroetz. ph –- Dietrich Lohmann. In colour. ed — Thea Eymèsz, a.d –- Kurt Raab, m -– excerpts from the work of Beethoven. songs -– “You Are My Destiny” by and performed by Paul Anka. l.p –- Eva Mattes (Hanni Schneider), Harry Baer (Hans Bermeier), Jörg von Liebenfels (Erwin Schneider), Ruth Drexel (Hilda Schneider), Rudolf Waldemar Brem (Dieter), Hanna Schygulla (Doctor), Kurt Raab (Factory Boss), El Hedi Ben Salem (Franz’s Friend), Karl Schedit and Klaus Michael Löwitsch (Policemen), Irm Hermann and Marquart Bohm (Police Officials). 9,180 ft. 103 min. Subtitles.

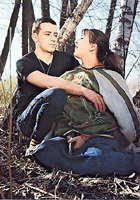

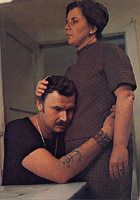

Hanni Schneider, fourteen, gets picked up by Franz Bermeier, nineteen, and loses her virginity with him in a hayloft. Soon afterwards, they meet in a restaurant on a day when Franz is off work because the freezer at the chicken slaughterhouse-factory where he works has broken down. Later, Hanni takes Franz back to her flat for sex while her parents are away…..Franz is subsequently arrested at the factory for sleeping with a minor; Hanni’s father, Erwin, is shocked when she is called in for questioning, and refuses to believe that she was Franz’s willing partner. Released seventy days before the end of his nine-month sentence on good behaviour, Franz continues to see Hanni secretly; Erwin slaps her when she lies to him about meeting Franz, and subsequently kisses and acaresses her violently in the heat of anger. Hanni’s mother Hilda tries to persuade her to wait until she finishes school before taking up with Franz, and tries to placate Erwin when he talks of castrating Franz. Hanni tells Franz that she is pregnant; they consider an abortion but reject this fearing that the doctor would report Hanni’s age to the police….Erwin finds a coat given to Hanni by Franz and tries to throw it out. After Franz tells Hanni that he wishes he had a gun to force her father to leave them alone, she acquires a revolver; telling her father that Franz wants to meet him in the country to make amends, she persuades Franz to shoot him dead when he arrives. The police turn up later to question Hilda and Hanni, and are puzzled by the latter’s evident lack of grief….In a prison hospital, Hanni blames her fate on her expected child….Outside a courtroom, where Hanni has just testified and Franz is waiting to appear, she tells him that their son was born deformed and died moments later. They agree that they weren’t really in love and that their attraction had been only physical.

A disconcerting example of Fassbinder at his near-best and near-worst, originally made for TV just after The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, Wild Game refers back to the Natalie Wood/James Dean relationship in Rebel without a Cause and other Fifties teen romances in order to wring some very bitter twists on the genre’s mythology — yielding ironies which reflect certain aspects of Pretty Poison while anticipating others in Badlands. An adaptation of a play by Franz-Xaver Kroetz which the author has disowned (calling Fassbinder’s attitude towards his characters “obscene”), it is marred by a needlessly elliptical and confusing narrative line, coupled with an uneven execution that seems to guarantee at least one over-done scene for every underplayed one. If the first scene between Hanni’s parents after Franz’s arrest seems a model of controlled understatement, in writing and acting alike, Erwin’s physical assault on his daughter is handled in the clumsiest and hammiest Bavarian sex-film manner (an impression reinforced by the fact that this section, like an earlier close-up of Harry Baer’s penis, was originally cut from the versions shown in German cinemas, and is reinserted here in poorly matched colour that contrives to give it an even cruder and more gratuitous effect). Similarly, in contrast to the unexpected dividend of a detailed camera tour of the slaughterhouse assembly line where Franz works, there are the mannerist tilted camera angles in the scene where Hanni produces a gun, before Franz lies down on the bed with her — a sort of fragmented formal idea corresponding to the fragmentation of plot, which omits such basic facts as how Hanni acquires the gun, how and why Franz’s relationship with her is first reported to the police, and any precise notion of how the murder is uncovered or who is likely to be penalized for it. There is a faint hint regarding the second mystery when Franz’s two work-mates call one another “swine” and “katzelmacher”, and it is implied that Dieter may have done the informing; but the perfunctory motivation remains, suggesting here and elsewhere an overall impatience with such connecting tissue, and a general concentration on each scene as an isolated unit. The performers are generally excellent, with Eva Mattes in particular making use of a highly creative repertory of attitudes and expressions. (Much less is required from Harry Baer, who is mainly used as an objet d’art out of the James Dean mould.) Jörg von Liebenfels and Ruth Drexel are fine in their early scenes together, turning into stock cliché figures out of Till Death Us Do Part or All in the Family only when the script offers them no alternative (“Under Hitler, he’d have learned his lesson in a concentration camp”; “Nazis had their faults too”, etc.). Vitriolic and characteristically glib in its depiction of its characters’ coarseness — Franz spitting in his hand to smear off Hanni’s lipstick, Hanni squealing delightedly and at length when she finds her father is definitely dead — Wild Game may well qualify as one of Fassbinder’s least compassionate films, even if it clearly designates its four leads as either villains (Hanni and Erwin) or victims (Franz and Hilda), with a great deal of sentimentality reserved for the latter. While it has been acclaimed rather curiously for its ‘political’ relevance – which is difficult to discern on any but the most hackneyed level — it does carry out at least an intermittent attack against the Fifties myth of teenage puppy love, challenging a few rickety archetypes in the process.

— Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1977, Vol. 44, No. 516