From the Chicago Reader, November 26, 1999. —J.R.

There’s surely no more famous lost film than Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, a silent film made in 1923 and ’24 and released by MGM in mutilated form in late 1924. If you believe the hype of Turner Classic Movies, what’s been lost has now been found —- even though the studio burned the footage it cut almost 75 years ago, in order, according to Stroheim, to extract the few cents’ worth of silver contained in the nitrate.

TCM’s ad copy states, “In 1924, Erich von Stroheim created a cinematic masterpiece that few would see — until now.” This is a lie, but one characteristic of an era that wants to believe that capitalism always has a happy ending, no matter how venal or stupid or shortsighted the capitalists happen to be. What TCM really means is that at 7 and 11:30 PM on Sunday, December 5, it will present a 239-minute version of Greed, which is 99 minutes longer than the 1924 release. The 99 minutes aren’t filled with rediscovered footage: instead the original release version has been combined with hundreds of rephotographed stills, sometimes with added pans and zooms, sometimes cropped, often with opening and closing irises. There’s also a “continuity screenplay” dated March 31, 1923, a new score, and varying amounts of ingenuity. According to Rick Schmidlin, who produced this version on video, “This will be the single largest premiere of a silent film in the history of cinema.” (The largest, that is, in terms of audience size, not screen size. And because it’s on video, the prospects for theatrical showings are dim.)

I hasten to add that it’s TCM’s ad copy I’m objecting to, not Schmidlin’s enterprise — which is a fascinating, instructive, and exciting undertaking, even if I have occasional bones to pick with it. In the interests of full disclosure, I should acknowledge that I was hired by Schmidlin as a consultant on another new version of a movie classic that was released last year by Universal Pictures, Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil. I was also asked by Schmidlin to be the consultant on this new version of Greed, an offer he made in part because of my short book about Greed published in the BFI Film Classics series in 1993. (I declined, mainly because there was no compensation. My employment by Universal had seemed close enough to charity work; it was demoralizing to think of performing comparable services for the Turner empire for no fee at all, even if I supported what Rick was doing.)

One advantage to watching from the outside is that I can now appreciate the difficulty everyone else had in sizing up the re-edited Touch of Evil. For all the major differences between the reconfigured Touch of Evil and the reconfigured Greed, neither qualifies as a “restoration” or a “director’s cut,” regardless of what Universal or Turner might say. Unfortunately both new versions are based on documents that aren’t publicly available in their entirety, which makes it difficult to evaluate the end product. The reconfigured Touch of Evil is based on a 58-page memo written in 1957 by Welles to the head of Universal, Edward Muhl, requesting editing and sound changes. Roughly two-thirds of this document became an appendix of the second edition of Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich’s This Is Orson Welles, a book I edited for HarperCollins in the early 90s. But no one apart from Schmidlin, editor Walter Murch, myself, and a few others has seen the entire memo.

The documents used to construct the new Greed include the aforementioned continuity screenplay and more than 650 stills, all of which Schmidlin came across in the Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles when he started researching the film. None of these items is available to the general public. One can get another version of the script edited by Joel Finler and published in London in 1972, and many stills have been published elsewhere, including the 400 stills printed in a book assembled by the late Herman G. Weinberg, hyperbolically titled The Complete Greed (1973). Still, here too we have only a partial guide to what motivated Schmidlin’s major decisions. This is hardly atypical. Similar gaps — and in most cases much bigger ones — exist in the documentation of the major artistic decisions made in virtually every movie. Nevertheless, most reviewers and many viewers proceed to make their judgments as if they knew all the essential data.

If you have any interest in Greed, you can’t afford to miss this version, though if you miss it on TCM I suspect you’ll eventually get a chance to see it on video. But I’m most interested here in discussing some of the gains and losses involved in such an enterprise, and in speculating about why projects of this kind are so popular nowadays. What do we want from such upgrades of familiar classics — and what do we get?

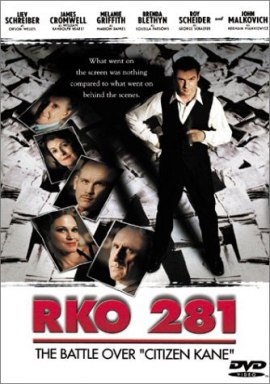

I’ll start with the second question. In August we got a horrendous “realization” of Welles’s unrealized screenplay The Big Brass Ring on cable. The rewrite was so extensive that it bore about the same relation to the original that Sleepy Hollow bears to Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”— in fact, it has even less relation to the original. The Tim Burton movie trashes Irving’s plot and characters, but at least it has more or less the same setting. This version of Welles’s script radically changes the plot and characters and the settings: parts of Spain become Saint Louis, and Africa becomes Cuba. What’s left is an embarrassment, even though the filmmakers think they’re basking in Welles’s reflected glory. Now we’re supposed to be grooving on a typical TV movie, RKO 281, about the making of Citizen Kane; it’s based on a poorly researched and intellectually dubious documentary feature comparing Welles with Hearst (which was of course nominated for an Oscar). And we’re supposed to be eagerly awaiting Tim Robbins’s The Cradle Will Rock, a theatrical feature about Welles’s production of a socialist opera that’s also reportedly an ill-considered hatchet job.

Plenty more Welles spin-offs have been announced. My favorite was heralded in the October 8 issue of Variety, in a story by Michael Fleming reporting plans “to turn the Orson Welles film The Magnificent Ambersons into a four-hour miniseries that will shoot next summer in Ireland. The mini will be faithful to Welles’s original script, something that could not be said of the original 1942 film. Welles turned in his cut and while he was on vacation, RKO cut nearly an hour and burned the original footage so Welles couldn’t restore it.

“`We have considered a number of possibilities for The Magnificent Ambersons, but we liked this one because this will convey the power of the original script and is consistent with Orson’s original vision,’ said RKO Pictures CEO/chairman Ted Hartley, who will be exec producer.”

I love that phrase “while he was on vacation.” So much for the months Welles spent organizing and directing It’s All True in Latin America, portions of which are now in danger of being lost forever because no one’s interested in raising money to preserve the footage. This was one of the many topics addressed at a four-day conference in Munich in late October on Welles’s unfinished films, which I attended along with Welles scholars from eight countries and two of Welles’s major collaborators, Oja Kodar and Gary Graver. There was also a lot of discussion about the restorations or completions of, among other films, Don Quixote, The Other Side of the Wind, The Deep, and The Magic Show; recent restorations of previously unseen television films made by Welles in the 50s and 60s were also shown and evaluated. The American press, film magazines included, showed no interest in this event, though it has shown a great deal of interest in all the bogus spinoffs — perhaps because only the spin-offs are capable of lining the pockets of American suits. (Fleming also notes that RKO is considering a stage musical based on Citizen Kane and developing an early unrealized Welles script, The Way to Santiago.) Over the years I’ve come to believe that any CEO or journalist who refers to Welles as “Orson” is automatically untrustworthy.

Fleming’s story about the new The Magnificent Ambersons is headlined “Orson’s revenge” — reflecting some ludicrous fantasy that a four-hour miniseries based on the script of Welles’s mutilated masterpiece should somehow garner his posthumous approval.

I don’t mean to imply that Schmidlin’s work on Greed belongs in the same category as the Welles rip-offs that are attracting such respectful attention from the media. In late October Schmidlin showed his version of Greed at the silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy — perhaps the most important annual event for film scholars, though it rarely makes waves in Film Comment (apart from an article about the new Greed in the current issue by Richard Koszarski, who also served as consultant on this version). But he can’t prevent TCM and its publicists from headlining this event “Erich’s revenge” if they want to, just as we who worked on the new version of Touch of Evil couldn’t prevent Universal from mislabeling the old preview version on video “the director’s cut” and a “restoration” only a month or so before our version premiered.

The big companies are so often unreliable when describing their products — and the press is so often reliable about rubber-stamping the companies’ ad copy — that it’s hard to decide how serious or frivolous these projects ultimately are. For sound advice, the public can’t really count on sources such as the New York Times, which promoted the American Film Institute’s first popularity poll with more fervor than it showed the reconfigured Greed. And the public shouldn’t entirely trust TCM, even though it’s a much more responsible organization than the AFI when it comes to film history. (If this sounds like an exaggeration, consider the AFI’s latest promotional venture, done in tandem with the studios and their video labels — a poll that purports to determine the greatest American comedies, even though it doesn’t list the single greatest American sound comedy, Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux, among the 500 nominees on its “official ballot.”)

It’s worth speculating on some of the factors that make MGM’s savage recutting of Greed such a legendary event. According to critic Stuart Klawans in his new book, Film Follies: The Cinema Out of Order, “The version released by MGM on December 4, 1924 — to commercial disaster — has been sought out by relatively few people. The film envisioned by Stroheim can’t be seen at all. Greed therefore exists primarily as an idea about filmmaking, which has passed among directors and writers, critics and moviegoers, for three-quarters of a century. A reputation for exhaustive veracity — whether to physical details or to the book — is a large part of this legend. With it comes another idea, which is even stranger considering Stroheim’s efforts to efface himself from Greed. The film, or its legend, is central to the idea of Stroheim as an author.”

Welles may be better known today than Stroheim, but Stroheim casts the more imposing shadow as a martyr at the hands of Hollywood studios (he also had more chutzpah when it came to spending the studios’ money). Both directors essentially got their way on the editing and release of their first features only, Blind Husbands and Citizen Kane (though Stroheim was so incensed by Universal’s release title — his own title was The Pinnacle, which studio head Carl Laemmle nixed because it sounded too much like “pinochle” — that he took out an ad in a trade paper denouncing the studio for this change). But after Welles’s ties with Hollywood became uncertain in the late 40s, he at least occasionally had low-budget European financing to turn to; Stroheim gave up directing after the debacle of his first sound picture, Walking Down Broadway (brutally edited and partially reshot by others), and worked only as an actor for the remaining 24 years of his life, mainly in Europe. Moreover, the destruction of his work went much further than it ever did with Welles’s; of the 446 reels shot for Greed, yielding a rough cut lasting eight or nine hours, all but 140 minutes were destroyed by MGM. His second feature, The Devil’s Pass Key (1920), hasn’t survived at all; Foolish Wives (1921) — to my mind as great, complex, and accomplished as Greed — ran for six and a half hours in rough cut, and less than a third of it survives today. (“They are showing only the skeleton of my dead child,” Stroheim announced at the time of the film’s release.) Stroheim was fired as director of Merry-Go-Round (1923), after about six weeks of shooting. I’m not clear how much was cut from The Merry Widow (1925), but the second part of The Wedding March (1928), a full feature, was lost in a fire at the Cinémathèque Française. Queen Kelly (begun in 1928) was never finished because Stroheim was fired in the middle of shooting and never given a chance to edit his footage.

Given this unhappy record, it’s a miracle Stroheim lasted as long as he did as a studio director. But he did because most of his released movies turned a profit. Whether any of his cuts of Greed would have been profitable is hard to say, but it’s difficult to understand how Hollywood apologists can argue that Irving Thalberg was justified in eviscerating Greed for business reasons, given that the movie that was released made back less than half its budget.

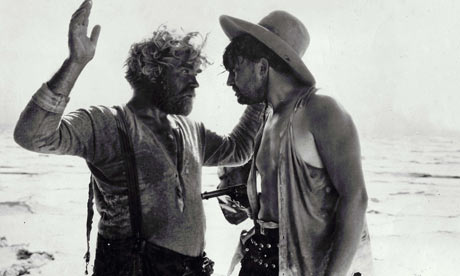

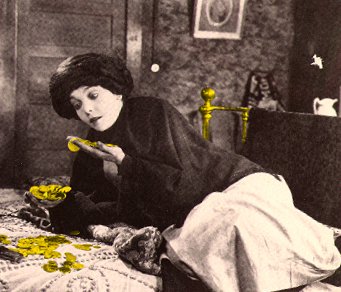

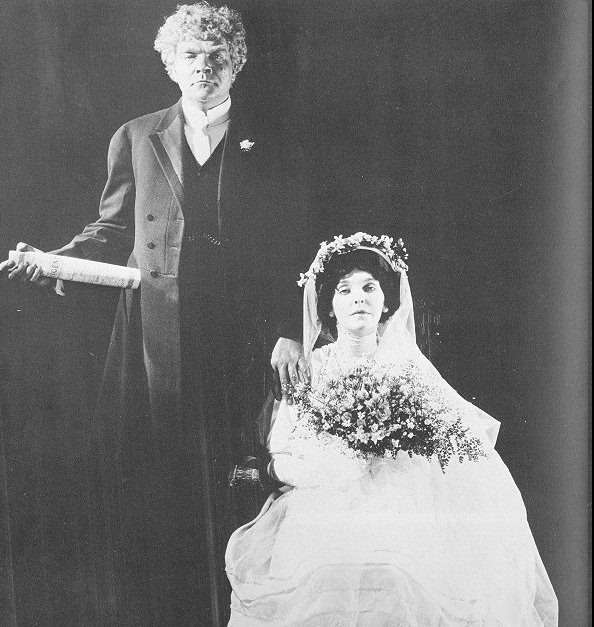

As an act and as a statement, the movie clearly got under Thalberg’s skin, and under the skin of the man who ran the studio, Louis B. Mayer. For Greed has to be the most negative depiction of what money can do to people that exists in movies (curiously, it has never been taken up as a cause by Marxist critics, at least not for ostensibly Marxist reasons). To summarize its plot in a couple of breathless sentences, it tells the story of how two devoted best friends in San Francisco, Mac McTeague (Gibson Gowland) and Marcus Schouler (Jean Hersholt), and Marcus’s cousin in Oakland, Trina Sieppe (ZaSu Pitts), who marries McTeague, wind up destroying one another after she wins $5,000 in a lottery. Trina gradually loses her mind, Mac loses his job as a dentist, both see most of their kindness and gentility progressively chipped away, and Marcus betrays both of them out of envy. Their mutual destruction is an extended process, described with a great deal of delicacy as well as brutal directness, and part of the story’s greatness — in Frank Norris’s novel McTeague (1899) and in Stroheim’s magisterial adaptation — is the degree to which it makes the deterioration of all three characters terrifyingly real and believable.

Some of the worst damage done when MGM reduced the original was to make this process seem at times forced and abrupt rather than a logical and organic development of these working-class characters, all of whom are treated as sympathetic as well as horrifying at various junctures. Marcus remains a relatively coarse figure throughout, but Mac and Trina, for all their limitations, are two of the most complex and multifaceted characters to be found anywhere in movies. This is arguably even more the case in Stroheim’s movie than in Norris’s novel, thanks to the remarkable performances of Gowland and Pitts, who succeed in incarnating these people, so that they seem to exist between the shots and sequences as well as during them.

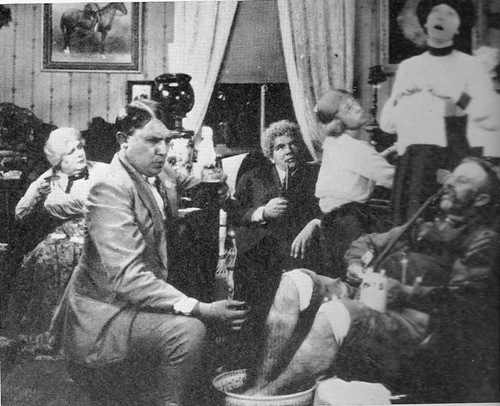

Schmidlin’s four-hour version makes these two much more solid. The stills and additional dialogue expand their essences, and four other characters that make up two couples (three of whom are missing from MGM’s original release) provide musical rhymes and stylistic and thematic contrasts that help define Mac and Trina. One of the couples is much more genteel: Old Grannis (Frank Hayes) and Miss Baker (Fanny Midgley) are shy, elderly neighbors of Mac and Marcus who live next door to each other in the same boardinghouse, each secretly nurturing romantic longings for the other, and who eventually get married. The images of their conjugal bliss are rendered in full color — one of the most startling and satisfying effects in the four-hour Greed, though, like every other glimpse we have of the two characters, it’s conveyed only through stills. This poetic subplot — like the running motif of Mac’s close kinship with birds, which becomes labored during a stretch of “significant” crosscutting when Mac’s lovebirds are menaced by a cat — reeks of D.W. Griffith’s influence. (Griffith gave Stroheim his first movie job, as an extra on The Birth of a Nation, and hired him again on Intolerance.)

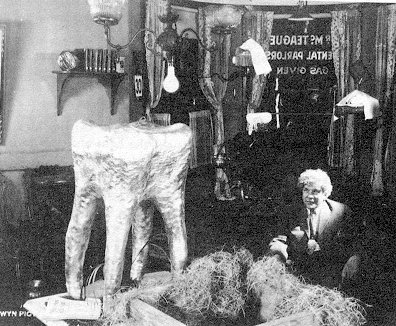

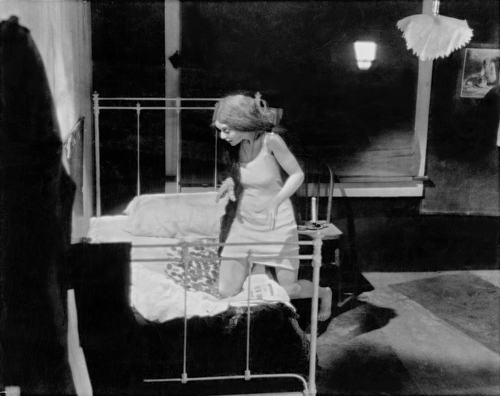

The other couple is Maria Miranda Macapa (Dale Fuller), the mad Gypsy woman who sells Trina the winning lottery ticket, and Zerkow (Cesare Gravina), a grotesque junk dealer. Their grim relationship is driven by greed and mutual mistrust and lighted and framed mainly in an expressionist manner. After Maria fantasizes at length about a solid-gold service once owned by her parents in Central America, Zerkow becomes obsessed with the notion that she’s hidden it somewhere, eventually slits her throat when she won’t tell him its whereabouts, then drowns himself in the nearby bay.

Putting it broadly, Old Grannis and Miss Baker represent Mac and Trina’s higher instincts, and Maria and Zerkow represent their baser impulses — a symbolism that’s underscored by Mac’s living in the same boardinghouse as Old Grannis and Miss Baker when he’s starting out as a dentist and his eventually moving with Trina into Zerkow’s abandoned hovel after he loses his practice. Norris uses these supplementary characters and settings the way a painter might use colors, to enhance and echo his main subjects; Stroheim adheres to the same overall principles, yet through the powers of his imagination he makes even more out of them. Contrary to the absurd legend that Stroheim simply “filmed” Norris page by page, nearly a fifth of the plot in the script published by Lorrimer — recounting Mac’s life prior to his arrival in San Francisco — transpires before he’s found eating his Sunday dinner at the car conductors’ coffee joint, the subject of the novel’s opening sentence.

Given the mixture of visual styles — and the dabs of gold added to appropriate objects in Schmidlin’s version, following indications in the continuity screenplay, and symbolic inserts of grotesquely long, bony hands fingering gold coins — it simply won’t do to call Greed a triumph of realism, as many have. Clearly some of it is and some of it isn’t. One thing that isn’t realistic, for instance, is the movie’s ambiguous and multilayered time frame. Stroheim updated Norris’s plot, though not always consistently, from the end of the 19th century to 1908 and afterward, corresponding to the period of his own first years in America. As a result, sometimes the major characters are dressed in the clothes of the 1890s (fidelity to Norris), the extras in crowd scenes are dressed in the clothes of 1923 (fidelity to the present, when the film was shot), and the stated time of the action falls roughly in between these periods (fidelity to Stroheim’s autobiographical impulses). Anticipating the jokey walk-ons of Alfred Hitchcock in his own pictures, Stroheim can be glimpsed in one of the stills as a balloon seller plying his trade on the street with Mac and Trina — a detail that can be interpreted as realism and as an in-joke at the same time.

On another level, Greed isn’t merely a novelistic account of what happens to certain people but a history of the vicissitudes of certain objects — which becomes much clearer in the new longer version. The progress and fate of Mac and Trina’s wedding photograph — as an imposing object that hangs in their bedroom, as a lost and later found emblem of their love for each other, as an item bitterly thrown away with the trash, one torn half of which is used to make a wanted poster for Mac — becomes a condensed version of the entire story, one that recasts it in an even more disquieting light.

McTeague is surely a great novel, but one reason Greed is even better is that Stroheim had more lived experience to bring to the material. Norris, a millionaire’s son and a gifted slummer, started writing McTeague in a creative-writing course at Harvard; the novel is dedicated to his teacher, and the first dental appointments Trina has with Mac are scheduled at the same time as Norris’s classes. Stroheim was the son of a Jewish merchant in Vienna who persuaded virtually everyone in Hollywood and western Europe — Orson Welles was a notable exception, at least by the 50s — that he had links to the Austrian aristocracy (a justification for the “von” in his name). The truth about his origins and the fact that he was a deserter from the Austrian army emerged only after his death, so he carried out his impersonation quite successfully from 1909, when he arrived in America at age 24, until his death in Paris, in 1957. The formidable antihero played by Stroheim in Foolish Wives is also an impostor, and part of the fascination of Stroheim’s filmography is its many brushes with autobiography. The poverty and physical abuse in Greed, for instance, can be traced back to Stroheim’s early years in America and to his painful first marriage.

***

Part of what’s objectionable about TCM’s claims that the four-hour Greed allows us at long last to see Stroheim’s “original” masterpiece is that it isn’t clear which version they have in mind. Nobody seems to know what’s meant by “the uncut Greed,” because there are so many choices. The private screenings of the rough cut held by Stroheim in early 1924 were probably not all screenings of the same rough cut with the same length. One source mentions 47 reels (almost ten hours) that were later reduced to 42. Writer Harry Carr describes watching a 45-reel version from 10:30 AM to 8:30 PM, and writer Idwal Jones mentions 42 reels lasting from 10 to 7. Someone else recounts seeing an eight-hour version. Considering all the things that can transpire at screenings — projector breakdowns, pauses between reels, breaks for meals — all these accounts might refer to the same rough cut, but that seems highly unlikely. The next version edited by Stroheim — 22 reels according to MGM, but either 26 or 28 according to Grant Whytock, who was then asked by Stroheim to edit a still shorter version — must have been longer than four hours as well. Whytock’s version ran to either 15 or 18 reels — nobody seems to agree about the lengths of any of the successive versions, maybe because they were all in constant flux — and was designed to be shown over two evenings; the subplot involving Zerkow was eliminated from this cut, but the subplot involving Old Grannis and Miss Baker was apparently retained. All these versions were thrown out for the sake of the ten-reel version eventually released by MGM. At the time of this release the New York Times — as dedicated to the art of film in 1924 as it is today — actually praised MGM for reducing the film to ten reels, though the reviewer hadn’t seen any of the earlier cuts.

***

Working on the reconfigured Touch of Evil, I discovered that one couldn’t delete or alter any single shot without affecting everything else, sometimes in subtle and mysterious ways. The same thing has to be true of Greed, and one of the most pronounced pleasures I had in watching Schmidlin’s version was seeing much of the older footage as if for the first time. Again and again I found myself asking of a particular scene, “Did I really see this before?” In every case I had — there’s no new footage apart from the stills and additional dialogue in intertitles — but the extra dialogue often has the effect of giving the old footage a fresh appearance.

I prefer to regard this four-hour Greed as a study version, an indication of what some of the longer versions of the film must have been like — since it clearly isn’t a replica of any of those versions. Even with more than 650 stills, the material available as possible additions was limited, and it appears that in most cases Schmidlin opted for clarifying the main story because that’s what the stills allowed him to do. For instance, the iris out on the train carrying away the Sieppe family near the end of part one, after the wedding of their daughter to Mac — an image that reminds me of the beautiful iris closing out a section midway through The Magnificent Ambersons — doesn’t appear in this version. Is this because no still of that shot was available, because the continuity script eliminated that shot, or for some other reason? I have no way of knowing, but the first reason seems the likeliest. (Also, early on, Schmidlin had to wrestle with how to repeat sections of the recent score by Carl Davis to fill what was then a three-hour running time; happily he was able to negotiate an extra hour and a new score, by Robert Israel, which, however uneven, is a vast improvement.)

With some entire dramatic scenes reduced to a few stills, you can’t indicate what a six- or eight-hour movie might have been like. I especially regret the nearly complete absence here of a long early sequence covering about 30 pages in the Lorrimer script that recounts what most of the major characters do on a “typical” Saturday—the day that precedes the novel’s opening—before most of them have met one another and before we’re sure what most of them have to do with the main story. This almost nonnarrative stretch, which would undoubtedly still seem radical today—like an endless series of digressions—foregrounds Stroheim’s manner of accumulating details into a solid, forceful mass while suspending storytelling in the usual sense. I’m fairly convinced that Harry Carr must have had this sequence in mind when he compared the 45-reel version of Greed to Les miserables and wrote, “Episodes come along that you think have no bearing on the story, then 12 or 14 reels later, it hits you with a crash.”

So this version of Greed isn’t everything — nor could or should it be. Greed will always be unfinished and incomplete, just as Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons will be. Contrary to rumor and propaganda, capitalism doesn’t always have a happy ending. But Schmidlin’s work can allow us to use our imaginations to construct what might have been, an inconclusive activity and, for precisely that reason, an exciting prospect — because it requires our creativity and not simply our desire to take in a great movie and then be done with it. A perpetually unfinished masterpiece throws the ball into our court, which is precisely where it belongs.