This article appeared in the April 1989 issue of The Independent (vol. 12, no. 3); slightly tweaked in late January, 2010. –J.R.

Having attended the San Sebastian Film Festival on two separate occasions 16 years apart — in 1972 and 1988 — I find it surprising how little the basic ambience of the event has changed.. Apart from the fact that the festival has grown, the major differences that I noticed are those between Franco and post-Franco Spain. One no longers buys a copy of the International Herald Tribune on the Avenida de la Libertad only to find that a state censor has neatly clipped out an article or two from every copy. Even more noticeable, to the eyes as well as ears, is Basque, a language that was rigorously outlawed under Franco. One now sees it on street signs and hears it on TV. One of the many sidebars of the 36th International Film Festival at San Sebastian was even devoted to Basque films.

Sidebars, in fact, have for a long time been the festival’s strength. In 1972 there was a Howard Hawks retrospective, with Hawks himself attending as a jury member for the films in competition. Back then, the festival was held in July, and was still small enough to offer excursions for all the guests” a bus ride to Pamplona to attend the bullfight encouraged Hawks to divulge some of his favorite Hemingway stories.

In contrast, the main selections at San Sebastian tend to be relatively mainstream and unexceptional. A few titles that I recall from 1972 are Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner, Carol Reed’s Follow Me (his last film), Alastair Reid’s Somthing to Hide, Tom Gries’ The Glass House, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze’s L’homme au cerveau griffé, and Peter Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc? These selections were shown at the Victoria Eugenia, a large opera house that continues to show the films in competition and also houses the festival’s offices, press room, video screening facilities (for the market), and a large café-restaurant. The Victoria Eugenia is located directly across from the Maria Cristina, the hotel which puts up the festival’s VIPs and houses the press conferences (which are televised daily). Visitors who want to stick close to the main events tend to mill about the same large block and around the same plaza.

Some visitors, like myself, find reasons to stay away from the main events. To attend one of the evening galas usually means a bit more than just dressing up.It entails walking up a grand stairway under a line of crossed swords held by uniformed soldiers. If one decides to leave a film before it’s over, there’s no easy way of doing so unobtrusively. As I recall from 1972, the side exits tend to be locked, and one has to leave down the same grand stairway, flanked by the same soldiers and other evidences of festival pomp. Once outside, it is no unusual to be approached by children and asked for an autograph, regardless of who one is. Because of my memories of all this, as well as a strong interest in the sidebars, I stayed away from all of the galas in 1988. Various friends and colleagues, however, testified that this aspect of the festival largely remains the same. The festival has a substantial annual budget, and putting on a display for tourists is part of what the event is all about.

All three of the major sidebars in 1988 were exciting: a Jacques Tourneur retrospective (accompanied by the publication of a 250-page, large-format book on the director), and broad and multifaceted retrospective devoted to “The ABC of Latin American Cinema,” and a novel series called “You Only Live Once,” devoted to filmmakers who had made only one film — a varied, eclectic group that included, among many others, Marlon Brando (One-Eyed Jacks), Albert Finney (Charlie Bubbles), Jean Genet (Chant d’amour), Charles Laughton (The Night of the Hunter, see above), Leonard Kastle (The Honeymoon Killers), André Malraux (L’espoir), Karl Malden (Time Limit, see above), Lorenzo Llober (Vida en sombras), and Peter Lorre (Der Verlorene).

Jacques Tourneur, mainly known for his remarkable films made for producer Val Lewton in the forties (Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Leopard Man) and his classic film noir Out of the Past (1947), was previously honored with a retrospective at the Edinburgh Film Festival in the 1970s and has long been a cult figure in France. In the U.S., he remains a neglected and barely known figure. The son of the very cultivated (and equally neglected) directed Maurice Tourneur, who began and ended his career in France (1912-1914 and 1928-1948, respectively), but worked as a major Hollywood director for most of the teens and twenties, Jacques also worked on both sides of the Atlantic. (His first five films were made in France during the thirties.) Unlike his father, however, he did virtually all of his major work outside of France.

Known as the director who almost never turned down an assignment, Tourneur left behind a variable and uneven body of work, a surprising amount of which remains distinctive as well as personal. Ironically, for a filmmaker who habitually insisted on using on-screen lighting sources, he is deservedly known as a master of off-screen space. This trait comes to the fore in his Lewton films (see above still, The Leopard Man) and the remarkable English horror film Curse of the Demon/Night of the Demon (1957), where the unseen becomes the “open, sesame” of the spectator’s imagination, but it is equally pertinent in much of his other work.

His own personal favorite among his movies — a nostalgic small-town idyll with Joel McCrea, Ellen Drew, and Dean Stockwell called Stars in My Crown (see above) — was improbably made at MGM in 1950. A film that bids comparison with John Ford’s The Sun Shines Bright, Stars in My Crown focuses on a local parson (McCrea) and his family, but has none of the conservative religious piety one associates with Louis B. Mayer’s MGM. Tourneur rightly prided himself on his progressive treatment of blacks in his films. One episode in the film that deals with the refusal of a poor local black man (Juano Hernandez) to sell his property to well-to-do whites is especially striking for the wit and economy of its acting, scripting, lighting, and mise en scène.

Some of Tourneur’s most interesting and visually striking pictures were adventure films in color: The Flame and the Arrow (1950), Anne of the Indies (1951), and Way of a Gaucho (1952) are three strong examples [see below].The even more conventional and formulaic Appointment in Honduras (1953) is striking in the particularly Tourneuresque way it is set mainly in exteriors while conveying the cozy atmosphere that one usually associates with interiors. Westerns such as Canyon Passage (1946) and Wichita (1955) are equally deserving of rediscovery. While Tourneur seldom seemed to have much of a hand in the scripts he directed, his best work conveys a finely tuned sense of ethics and a sensitive feeling for human interactions — both hallmarks of his direction. While the San Sebastian wasn’t quite exhaustive, it did manage to include a few of Tourneur’s TV films. A 30-minute show for General Electric Theater in 1960 entitled The Martyr, for example, offers a directorial feat of the first order: coaxing an unusually sensitive and subtle performance out of Ronald Reagan.

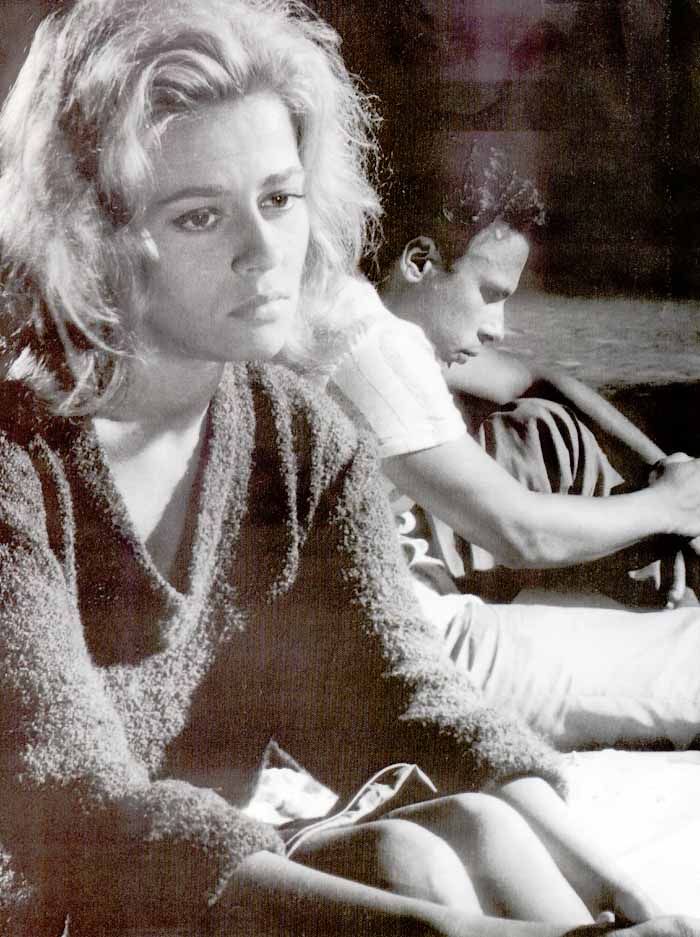

Of particular interest in the “ABC of Latin American Cinema” program were various films with considerable reputations but hardly known at all in the U.S. The best of these that I saw was a wonderful early black and white Cine Novo film by Ruy Guerra, Os cafajestes (1962, see below), an erotic tale about two petty blackmailers packed with filmic invention and energy. Very close in look and spirit to the early films of the French New Wave which were being made around the same time, the film was popular in Paris when it was released there. It seems like a historical accident that it never surfaced commercially in the U.S.

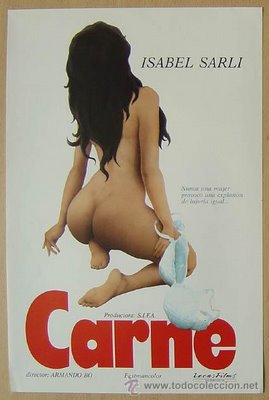

Others in the series that I saw or sampled included Raul Ruiz’s first completed feature in Chile, Tres tristes tigres (1968, see below), which intermittently demonstrates that his interest in “illogical” camera angles was there in his work from the beginning; an enjoyably lurid camp Mexican musical/melodrama, Alberto Gout’s Aventuera (1949, see below), starring the flamboyant Ninón Sevilla; and a revolting Argentinian exploitation cult item, Armando Bo’s Carne (1968, see below), which principally consists of the buxom heroine being repeatedly raped.

All of the sidebar events were held in a cozy multiplex cinema in the old section of town, an area surrounded by relatively cheap restaurants and frequented mainly by students. Shortly before the end of the festival, after a Basque terrorist was killed in a skirmish with the local police, a burning bus was ignited in protest, blocking one of the nearby streets. A couple of miles away and a few hours later, at the festival’s swank closing night party held at the Palacio de Miramar, San Sebastian glittered with a very different kind of light, sound, and fury.

— The Independent, April 1989 (vol. 12, no. 3)