From The Soho News, July 9, 1980. –J.R.

The Second Coming

By Walker Percy

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $12.95

If reading Faulkner is sometimes like going on a desperate and delicious three-day bender, perusing the clear-headed work old Doc Percy — a practical-minded (if nonpracticing) Southern M.D., now in his mid-60s — is usually more like taking a healthy antidote the next morning, and recovering one’s senses with dry irony and mordant wit. At least it has seemed that way up until now, to a Southern expatriate like myself who cherishes both writers (and a fellow moviegoer who appreciates what these very different noble Southern novelists have learned to steal from movies).

But The Second Coming — Percy’s fifth novel, after The Moviegoer, The Last Gentleman, Love in the Ruins and Lancelot — happily makes hash of this conceit by offering both pleasures in succession, the night before and the morning after, without so much as a hangover. How does Percy do it? Partially, I think, by splitting himself in two, like any self-respecting Gemini, and then making music out of his intertwining, alternating voices that ultimately merge: an old-fashioned love story, and one with a happy ending. Plotting out his narrative trajectory by crosscutting between Will Barrett and Allie Huger, who eventually compose his couple, he shrewdly fuses his existential and semiotic concerns with his style and story, to the point where you can’t even tell them apart.

Faulkner worked with narrative counterpoint, too, but differently — in Light in August (split between Lena Grove and Joe Christmas) and The Wild Palms (split between two separate, nonconverging narratives about love). Cinematic crosscutting principles are already quite evident — The Wild Palms even contains a passing reference to Eisenstein — but the calculated avoidance of any synthesis of these parallel lines is clearly a romantic’s solution.

Walker Percy, a classicist and a Catholic, obviously has different fish to fry, and a different range to fry them on. His meanest small-town targets, like Flannery O’Connor’s, are always genuine Dixie mediocrities (check out Ewell McBee here, with his “Jarmar Sansabelt slacks and shirt-sleeve white shirt,” or Barrett’s born-again daughter Leslie, or all his characters who say “There you go”), while Faulkner’s Snopses are mainly too mythic or awful to qualify. As far as existential dread, metaphysical decor and class behavior are concerned, The Second Coming is actually closer to Sontag’s Death Kit than to anything by the author of As I Lay Dying. (If Percy were less modest, he could have called this book Life Kit.)

Like Faulkner, though, he’s smart enough to realize that what we bring to movies may turn out to be even more complex than what movies bring to us. “Who is he,” he asks in his beautiful 1956 essay “The Man on the Train” (included in The Message in the Bottle), “this Gary Cooper person who manages so well to betray nothing of himself whatsoever, who is he but I myself, the locus of pure possibility?”

***

Will Barrett — a fiftyish, multimillionaire widower and golfer in Linwood, N.C., roughly twice as old as he was when he last encountered him, as the title hero of The Last Gentleman (Percy’s remake of The Idiot) — gradually loses his mind, and escapes from home and country club. Meanwhile, Allison Huger — troubled daughter of Barrett’s onetime girlfriend Kitty Vaught, in her late teens or early 20s — escapes from Valleyhead Sanitarium, sets up house in an abandoned greenhouse she has inherited, and gradually schools herself in sanity.

The alternation of chapters between these characters is a kind of conceptual counterpoint, and the formal symmetries that they make together are intricately worked out. Will gets blackouts and keeps falling down, Allie brightly keeps hoisting him (and other things) up. Her greenhouse, into which he literally falls from a cave, is a fairy-tale cottage; his cave — where he goes in search of a sign from God — summons up Plato’s parable.

Following both of these klutzy, lovable eccentrics, Percy’s temperate style passes repeatedly over the same incidents and ideas in their heads like an endlessly rotating, scanning searchlight, each time teasing out and illuminating fresh aspects of their minds. And the most film-derived part of this method is to juxtapose their complementary natures via crosscutting long before they compose an actual couple. There’s even what filmmakers call a “match cut” between the end of Chapter 3 (“He remembered everything”) to the beginning of Chapter 4 (“She remembered nothing”).

What he remembers includes his father’s first attempt at violent suicide, while what she forgets includes recent electroshock at the hospital. Both of these facts gradually expand, like film sequences in repeated Proustian playback, as concepts that are central in molding the identity of each. To engineer her escape from Valleyhead before she knows she’s getting electroshock, she writes herself a letter to read afterward –“Instructions from Myself to Myself” — splitting herself in two. To engineer his own retreat into a cave, he writes two letters, one to an uncle of Allie’s named Sutter Vaught — something of a straw man, as it turns out, for the character never gets the outrageous letter or puts in a single appearance.

Part of Percy’s devious strategy has always been to scatter red herrings like daisies wherever he goes. In The Last Gentleman, Sutter was the book’s Seymour Glass/Mr. Natural figure, both guru and spokesman; intriguing as he was, waiting for his next journal entry to appear was a little bit like getting ready for another Chinese fortune cookie. Here he’s half-promised and never delivered, and his failure to show up unexpectedly proves to be very satisfying. It’s nice to discover that Percy and Barrett no longer need him.

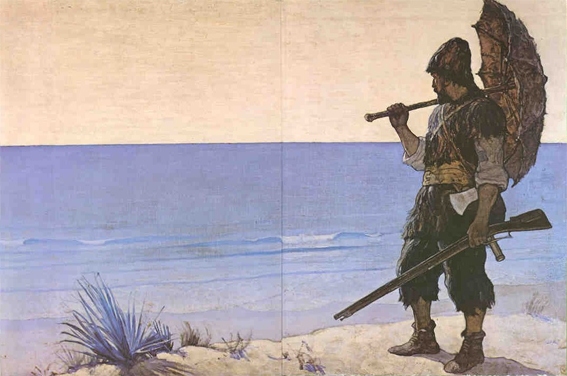

While the identity of Will appears to be dissolving like an Alka-Seltzer, the identity of Allie — who has to put together a workable self in order to live in the world — is going through a process of accumulation and growth. Much of the deepest pleasure afforded by The Second Coming is the pleasure of watching this slow accretion of existential anchors — spelled out by Percy in wise and generous detail that charmingly evokes Robinson Crusoe. While Will becomes increasingly convinced that the world is coming to an end because all the Jews in North Carolina are fleeing for Israel, Allie doggedly and patiently figures out what she needs to transport a stove into her greenhouse (rope, blocks and creepers), what they’re called, and how to get them.

“Imagine being born with gold-tinted corneas,” Allie thinks at one point, “and undertaking a lifelong search for gold. You’d never find it.” But silvery Will and golden Allie find one another because language-happy Percy lets them. There has often been a certain tension in his writing between his poetic instincts and the relative inelegance of philosophy and language theory, which commonly aims at correctness rather than grace. This may help to account for the rhythmic quirkiness of his prose, which genuinely appears to be composed sentence by sentence rather than paragraph by paragraph.

What makes The Second Coming seem like a decisive step forward is the degree to which questions about style and language become indistinguishable from questions about the characters and their spiritual health. Everything gets worked into the act of storytelling, coming out as naturally as breath. If the novel, as stated above, curiously combines the benefits of the night before and the morning after, this isn’t because either of Percy’s romantic leads “cures” the other. More precisely, it’s because Allie/Will does the job on Will/Allie, and vice versa.

Compare the fancy Faulknerian prose that is uncharacteristically occasioned at separate junctures by each character. Then notice how, in the scenes between them, Percy lets their verbal mannerisms — his recitation of dry bone facts, her taste for puns and rhymes — cross over and intertwine in tuneful duets.

Here’s Barrett recalling his father’s final attempt at suicide: “And what samurai self-love of death, let alone the death of everyday fuck-you love, can match the double Winchester come of taking oneself into oneself, the cold-steel extension of oneself into mouth, yes, for you, for me, for us, the logical and ultimate act of fuck-you love and fuck-off world, the penetration and union of perfect cold gunmetal into warm quailing mortal flesh, the coming to end all coming, brain cells which together faltered and fell short, now flowered and flew apart, flung like stars around the whole dark world.”

And here’s Huger settling down in her greenhouse: “One way to escape the longeurs of clock time marching out into the future ahead of her was to curl away from it, going round and down into her dog-star Sirius self so there she was curled up under, not on, the potting table….She lit a candle and the soft yellow light made a room in the dark and time went singing along with cicada music and not even the screech owl was sad except that just at dusk there rose in her throat not quite panic but something rising nevertheless. She’s swallowed it, all but the aftertaste of wondering: tomorrow will it be worse, even a curse?”

***

Even the proverbial end of the world and the death of the soul can be fun if it’s Walker Percy who comes to the last-minute rescue. Appearing in the midst of a cinematically barren summer, it is no great shakes to say that The Second Coming tops every new movie in sight. Perhaps it’s more to the point to say that, unlike most movies, Percy doesn’t leave us alienated afterward. Writing further about Gary Cooper in “The Man on the Train,” he notes that “Everything depends on his gestural perfection — an aesthetic standard which is appropriated by the moviegoer at a terrific cost in anxiety.” The Second Coming gives not a hoot for anybody’s gestural perfection. It is only concerned with mundane Southern matters — how to live, act and write, gracefully, responsibly and well.

— The Soho News, July 9, 1980