This essay originally appeared in The Soho News on December 3, 1980. I’ve taken the liberty of revising it slightly.–J.R.

Michael Powell and

Powell & Preesburger

Museum of Modern Art, Nov. 20—Jan. 5

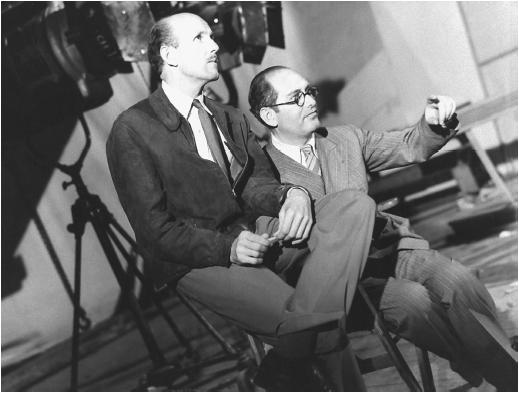

By and large, the Englishman Michael Powell directs, while his longtime Hungarian collaborator, Emeric Pressburger, writes screenplays. But when they started their own English production company, The Archers, in 1942 — an institution that lasted almost 15 years — the credits of their joint efforts usually read, “Written, directed and produced by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger”.

A testimony to the rare capacity for collaborative work that helps to distinguish English life and culture from American individualism, the team of P & P offers the working assumptions of auteur criticism a number of interesting challenges. On the one hand many aspects of Powell’s style, temperament and preoccupations can be traced through films that Pressburger didn’t work on. At the same time it would be too simplistic to pretend that one could separate individual contributions to their joint ventures with anything like total assurance.

Indeed, as Ian Christie reminds us in the introduction to his very helpful collection Powell, Pressburger and Others (British Film Institute, 1978), auteur criticism is more a method of reading films than a means of establishing how they were put together. There’s a concept of duality, in any case, that the Museum of Modern Art’s long-awaited and extensive (if not exhaustive) retrospective has wisely adhered to, even in its title.

Supported by detailed, informative, and affectionate program notes from film historian William K. Everson, this fascinating season has already been running for three weeks. But there are more than two dozen features to come, with lots of treats still in store.

***

Why is it that I find these films so difficult to write about? English to the core, there’s something elusive yet unavoidable in most of them that strikes my Continental temperament as anti-aesthetic — a curious kind of safety mechanism, activated somehow by their delirious imaginative qualities and their consummate craftsmanship, that prevents them from becoming too serious or purely conceptual or aesthetically/ethically ordered as art. (Their capacities to entertain, on the other hand, are rarely in question.)

Powell himself may have best pinpointed this tendency when he remarked, in an interview with Kevin Gough-Yates 10 years ago: “I have a very childlike view of life and art rather like Bonnard, a consciousness of art and common sense, but not terribly interested in it. Matisse, on the other hand, is a very cultured painter, where Bonnard is not cultured at all: he is just happy and having a lovely time, if you don’t mind the comparison with painters.” Laid-back syntax and all, that’s Powell in a nutshell.

Made two decades apart, The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and Peeping Tom (1960) may provide the best open-sesames into the expanses and limits of Powell’s fairy-tale cinema. They are not only his best movies, one could argue, but also the most revealing (auteurist) testaments -– even if one acknowledges that no fewer than five other directors worked on portions of the earlier film. And these films are possibly the most useful lenses through which to consider the rest of Powell’s work, each lens focusing the gaze of a romantically inner-directed, misogynistic child.

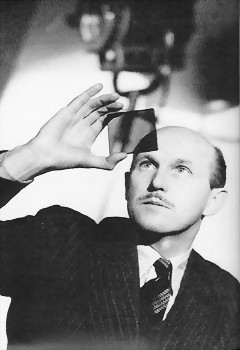

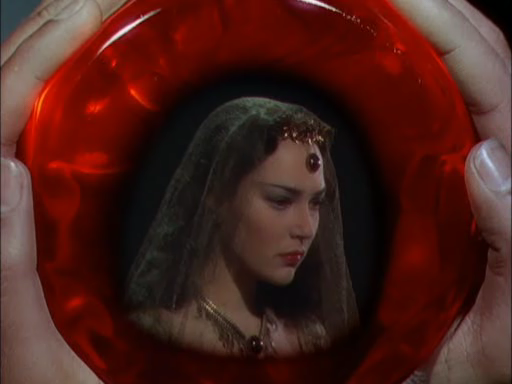

Start with an eye, looking either out or in, and you already have the most characteristic Powell motif. Among other instances there’s the painted eye on the prow of a ship and the magical all-seeing ruby of The Thief of Bagdad — both of them emphatically narrative eyes, leading one straight into male adventures (apparently the outward journey).

Peeping Tom, by contrast,juxtaposes two stationary, surrogate “eyes” focused on a more confined and static spectacle — the voyeuristic camera and the self-regarding mirror. These are grotesquely combined in a unique parody of sex and murder anticipating the concept of snuff movies, in a kind of killing photography whereby the demented hero’s camera shows his female victims their own horrified looks in a mirror, while a blade attached to the camera tripod pierces their throats.

These very different yet complementary masterpieces serve as persuasive evidence for the argument that the pleasure of moviegoing is essentially perverse, dangerous play. Thanks in part to their ingenious scripts — by Lajos Biro and Leo Marks, respectively — which serve as admirable vehicles for the free-floating energy of the mise en scène, they carry us a lot further into the asocial, narcissistic realms of film-watching than most movies are willing or able to go. Like the boat (with Powell himself as yachtsman) arriving at the spectacular, deserted island of Foula at the beginning of The Edge of the World (1937), or the underwater visions of a painter (James Mason) involving the young Helen Mirren in the Australian Age of Consent (1968), these forays always have something implicitly or explicitly dreamlike about them.

***

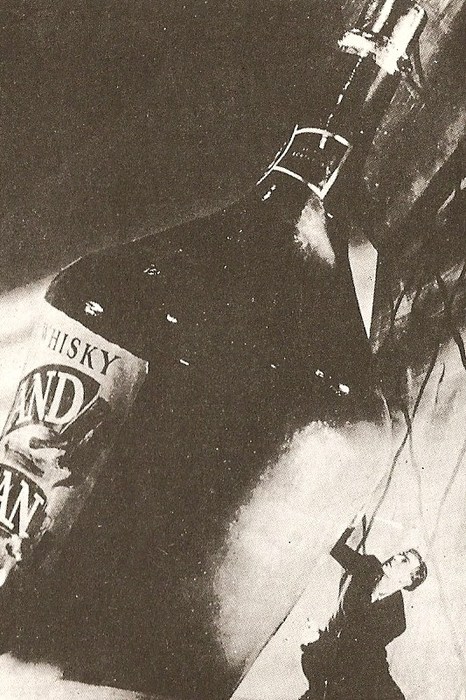

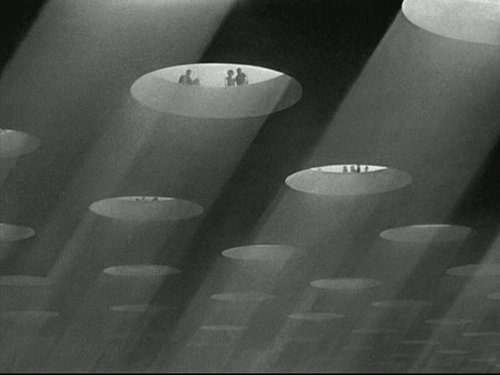

To be sure, comparable moments and images appear in Powell films with Pressburger scripts –ranging from the lovely special effects (involving animated flak and models) in One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942) to the gigantic, hallucinated whisky bottle in The Small Back Room (1949) to the Fantasia-like drifts of The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffman (1951). Significantly, Powell has described Walt Disney as “the greatest genius of us all”; and the Kitsch Master of Color is certainly evoked in the pictorial climax of P & P’s gorgeously loony 1947 feature, Black Narcissus, aided by the sets of Alfred Junge.

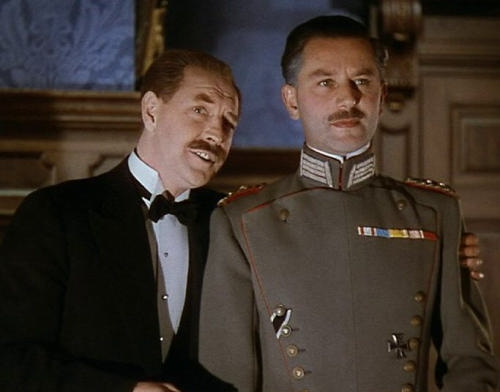

Yet despite these and other auteurist continuties with Powell’s other work, a more level-headed and perhaps more socially grounded sensibility seems to emerge in the films with Pressburger. One is tempted, in fact, to find some vestiges of their dialectical working relationship in the lifelong friendship between the Prussian (Anton Walbrook) and Englishman (Roger Livesey) in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), the first of their Archer productions that they wrote and directed.

In his notes on the full version of Blimp, Everson evokes the re-editing woes of Greed and the flashback structure of Citizen Kane. The other films I was reminded of, though, were both made in 1961 — Jules and Jim and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, each of which tries to tell history through a contrasting male duo.

More appealing (to me) are the mutual accords gradually arrived at in the courses of A Canterbury Tale (1944) and I Know Where I’m Going (1945). Both films are nearly plotless explorations of characters and locales, whose leisurely yet satisfying symmetries recall those of Hitchcock’s underrated The Trouble with Harry. (A principal difference between Powell and Hitchcock as artists relates to class — Hitchcock’s Cockney origins versus Powell’s more comfortable upbringing.)

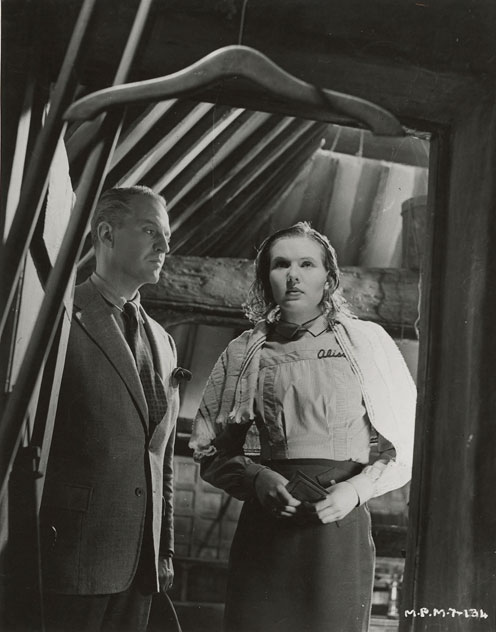

A Canterbury Tale winds up as an oddball defense of an antiquarian in Kent (Eric Portman) who pours glue in women’s hair as an indirect way of persuading servicemen to attend his lectures. Eventually, this Peeping Tom precursor, one of his victims, a cinema organist and an American officer all achieve a mystical wartime communion together in the Canterbury cathedral. The resolution of I Know Where I’m Going, by contrast, is strictly a romantic one in the Scottish highlands between a reformed golddigger (the fabulous Wendy Hiller) and an earthy Roger Livesey (P & P’s John Wayne, in more ways than one).

Indeed, it’s largely the sense of English wartime unity that invigorates a fantasy like A Matter of Life and Death (1946) — even if, as critic Raymond Durgnat argues, the movie can easily be read as a Tory critique of socialism, with its heaven parodying the bureaucracy of a welfare state. Without the complex truces between the social and asocial self that make up the English character, P & P movies often threaten to go flat — Gone to Earth (1950) is a fairly juiceless example — and it appears that World War II provided them with the best occasions to explore this tension.

—The Soho News, December 3, 1980