This book review appeared in the July 7, 1991 issue of Newsday. More recently (Christmas eve, 2014), I’ve read Susan L. Mizruchi’s instructive Brando’s Smile: His Life, Thought, and Work (Norton), which finds far more coherence in Brando’s career than Schickel did. — J.R.

BRANDO: A Life in Our Times, by Richard Schickel. Atheneum, 271 pp., $21.95

“Of the many illusions celebrity foists upon us the illusion of coherence, the senses that these are privileged people in the world who somehow know what they are doing in ways that we do not, is the largest, and possibly the most dangerous. But Marlon Brando has kept faith with his incoherence.”

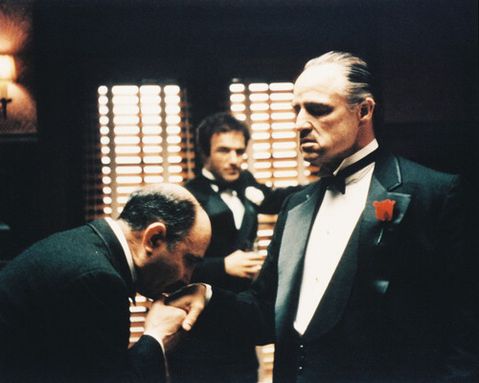

Arriving at this judgment toward the end of a head-scratching appraisal of the logic and meaning of Marlon Brando’s career, critic Richard Schickel seems to be breathing a sigh of relief, and some readers may feel like joining him. It’s an honorable and instructive admission of defeat, and while one may disagree by finding some coherence where Schickel does not — I happen to relish Brando’s modest and earthy performance in The Freshman as a refreshing autocritique of his posturing role in The Godfather (which Schickel considers his last “real” performance) — it’s still a premise that one can hang an exploratory book on.

Informing his critical biography with a personal, generational statement about what Brando has meant to him, as someone who entered adolescence in the mid-40s, Schickel’s study tends to get better as it proceeds, at least in the sense that it gradually abandons any pretense of coming up with a skeleton key to unlock all the mysteries it probes. Before it reaches this plateau of enlightenment, many theories are brought forth, ranging from the psychological (the consequence of Brando having alcoholic parents) to the aesthetic (the deleterious effects of CinemaScope on Brando’s career during the 50s). Most of these have some validity, but none can fully account for the dismaying dips, rises and detours that Brando’s acting career has taken from the 40s to the present.

One major roadblock along the way is a resistance on Schickel’s part to taking Brando’s political interests seriously. Dubious about the power of the 60s to radicalize anything but sex for his generation (“The idea that the middle-class Sixties college kids…were serious revolutionaries was preposterous”), Schickel can only balk at Brando’s rejection of his 1973 Oscar for Last Tango in Paris, and his use of that occasion to make an impassioned plea for the American Indian Movement (which he helped to found), followed by three years of related political activity.

“Perhaps as a result of his recent professional successes, perhaps because of the economic security it provided him, perhaps because he felt a need to justify his Oscar-night gesture, he took positions that were much more overtly radical than they had been in the past,” Schickel speculates, sidestepping the possible explanation that the plight of American Indians might have had something to do with Brando’s behavior. Faced elsewhere with the possibility (raised by Brando) that Gillo Pontecorvo, the Marxist director of Burn!, may have been hypocritically “exploiting and mistreating his native cast,” Schickel finds this notion not distressing but “delicious,” perhaps because it only confirms his scorn for the project.

This isn’t to say that Schickel necessarily dislikes political messages; he praises the anti-Stalinism of Viva Zapata! and singles out the more politically ambiguous On the Waterfront as his favorite, even though he admits that by the end of the latter “one really didn’t give a damn what the film was saying” (a point he later repeats about The Young Lions). The problem, rather, is that Schickel has more respect for the film industry and the acting profession than Brando does, and can’t understand why the actor has conducted his career accordingly.

At worst, this leads to some sloppy scholarship. “Search though one may, it is impossible to find any detailed comments about his work [in On the Waterfront] from Brando. This possibly betokens, of all things, satisfaction with it.” (It’s an interesting hypothesis, but only if one ignores Brando’s detailed and fascinating comments about the taxicab scene in Waterfront in Truman Capote’s “The Duke in His Domain” and Brando’s 1979 Playboy interview, neither of which suggests any satisfaction on Brando’s part.)

On the other hand, Schickel does an intriguing job of reading into A Streetcar Named Desire “a symbolic representation of the basic family drama that was crucial in forming [Brando],” and quotes some winning lines from a review by Stephen Sondheim of the underrated Guys and Dolls, taken from “an obscure and sober-sided film journal” that I wish Schickel had bothered to name.

It could be that Brando has never found a project since A Streetcar Named Desire that has been equally worthy of his talents, perhaps because this was the only time he played a full-fledged character whom he detested. Given Schickel’s partiality toward Brando as a sexual outlaw, beyond the pale of ethics, this isn’t a hypothesis that the author seems inclined to entertain, but it suggests a possible alternative route that puts his moral concerns and his gifts as a performer within the same arena. Maybe Schickel and I are both off the mark, but when Brando’s eagerly awaited autobiography appears, we’ll at least have some basis for an answer,

— Newsday, July 7, 1991 (slightly revised, December 2009)