This book review appeared in the August 27, 1980 issue of The Soho News.

I was moved to repost this review some time ago by the generous recent reference to it made by Sam Jordison in the Guardian. –– J.R.

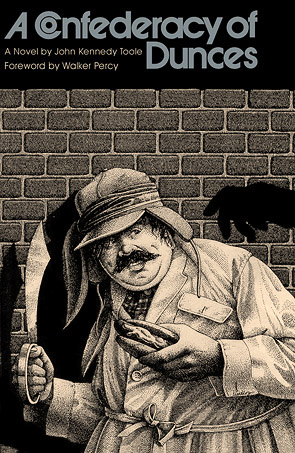

A Confederacy of Dunces

By John Kennedy Toole

Foreword by Walker Percy

Louisiana State University Press, $12.95

Is it by mere chance, or through some form of subtly earned tragic irony, that this brilliantly funny, reactionary novel is being published during a reactionary period, apparently about a decade and a half after it was written? God knows what it might have been like to read this in the mid-’60s. I suspect it would have been less warmly received — one reason, perhaps, why it wasn’t published way back then.

What I mean by Reactionary Humor is the boring literary schemes of Tom Sawyer, not the expedient escape tactics of Huck Finn. Broadly speaking, it’s what we learn to expect from the perennial antics of Blondie and Dagwood, Amos and Andy, Franny and Zooey, Laurel and Hardy (and Marie and Bruce, in Wallace Shawn’s recent play), not to mention W.C. Fields, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Archie Bunker, and Woody Allen.

One can even say that Reactionary Humor is what we get from Don Quixote — a figure mentioned twice by Walker Percy (along with Oliver Hardy and Thomas Aquinas) in the foreword to this remarkable, posthumous New Orleans novel, whose author killed himself at the age of 32. Or at least we get it until that terrible moment at the end of Cervantes’ novel, when the dying Don suddenly repudiates his delusions and finds himself.

The heroes and victims of Reactionary Satire are usually the same people. They live according to an improbable cosmic law that declares human personality to be an unalterable given, incapable of undergoing any development or improvement. Following this narrow philosophy — a familiar form of Southern comfort — one quickly arrives at the conclusion that one’s character, idiosyncratic warts and all, is as inescapable as one’s skeleton.

There’s an explicit economic reason for most Reactionary Humor. If neurosis (Woody Allen), corpulence (Oliver Hardy) and stupidity (Krazy Kat) continue to attract paying customers, who wants to see an Allen with his problems licked, a Hardy signed up with Weight Watchers, or a Krazy Kat enrolled in college? So, at the worst, one domesticates one’s problems by proxy, resigns oneself to their status as spoiled pets, and chuckles at their semi-permanence, rather than make any effort to solve them.

All of John Kennedy Toole’s preposterous characters seem mired in this condition — to the profit of nothing but the author’s despairing, affectionate scorn and slapstick. The diverse New Orleans inhabitants of a sleazy nightclub, city street, police station, factory office, and classy gay party vibrate with the same celestial ineptitude: a mainly unemployed fat slob with an MA who’s never gotten further away from home than Baton Rouge (the hero); his dimwitted mother and her dimwitted friends, including a pathetic cop named Patrolman Mancuso and an elderly suitor called Claude Robichaux who blames everything on “the comuniss”; and an assortment of other grotesques that what the hero calls Fortune keeps throwing in his bumbling path.

***

Learn how to think progressively in relation to a Fassbinder weepie or an Allen comedy — that is, speculate on what might happen if the characters could behave differently, were able to change and grow — and these artful entertainments no longer dispense their customary solace. Yet put the bars back on the cages surrounding these maladjusted freaks, and they regain their fascination, seem to become “fully rounded” figures again — possibly because they represent the sluggish, defeatist side of ourselves.

It’s hard to imagine anyone more fully rounded than Toole’s monstrous hero, Ignatius J. Reilly — a gargantuan, balloon-shaped medievalist and virgin who consumes many hot dogs, pastries, Dr. Nuts, and Doris Day movies. He has acute digestive problems involving his pyloric valve, wears absurd clothes (a green hunting cap, later a pirate suit), berates his arthritic and alcoholic mother (with whom he lives), writes in Big Chief tablets, and rails continuously against the modern world for its lack of “theology and geometry”. In other respects, Reilly is no more than a plump octave — the top and bottom notes in a silly scale of human frailty and disaster-prone pathos, conveyed through intricate plotting by all the other characters in Toole’s confederacy of dunces.

The novel’s title comes from Swift — “When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him” — but the measured loftiness of both the prose style and the elaborate plot construction intermittently suggests some of the finer tuning of an Alexander Pope. (A Dunciad of Confederates almost works as an alternate title.) The fact that Ignatius Reilly is a “true genius” and an obnoxious asshole at the same time, and to roughly equal degrees (with the asshole clearly having the upper edge), is an essential part of the overall comic vision.

***

It probably runs against the grain of the book’s calculated neoclassical “timelessness” to insist that the author has discernible political biases of his own. But run and insist we must, for the temporal setting of the novel — like the fact of Toole’s suicide in 1969 — becomes an unavoidable aspect of its meaning in 1980.

Based on some scant internal evidence — mainly the descriptions of a few movies seen by Ignatius — the action seems set around 1962, when the civil rights movement was already in full swing, but other fringe causes (like war resistance, feminism, and Gay Lib) had yet to receive much mass attention. It seems typical of the book’s defeatism, though, that all political activity in it be regarded as equally hopeless and misguided.

A fair amount of the author’s ridicule and venom is reserved for female liberals and liberationists — notably the horrendous wife of a jeans manufacturer, who insists on “rehabilitating” a senile office employee in order to torment her cynical husband, and Ignatius’ Bronx-based girlfriend and correspondent, Myra Minkoff (mainly a Woody Allen nightmare), whose Reichian projects seem similarly designed to provoke and infuriate the slob hero. Coincidentally or not, both these women are Jewish.

By contrast, Mancuso and Robichaux, the ostensible right-wingers in the book, are depicted as lovably harmless and ineffectual creatures — sweety-pie stooges. In separate episodes, Ignatius (another Catholic) improbably organizes black workers at the jeans factory and homosexuals in the French Quarter, for improbable anarchist reasons of his own; both schemes, partially designed to provoke Myna Minkoff in turn, predictably end in madcap disasters.

In his forword, Percy inadvertently comes on like an old-style Southerner when he celebrates a young porter named Burma Jones, a “black in whom Toole has achieved the near-impossible, a superb comic character of immense wit and resourcefulness without the least trace of Rastus minstrelsy.” Read that phrase in reverse, and you’ll see that Percy is implying that it’s nearly impossible to imagine “a superb comic (black) character of immense wit and resourcefulness” without some traces of Ole Rastus — a reactionary Southern bias that the funny but two-dimensional Jones partially reflects. Then there are the gay characters, whom Toole seems to fear even more than his female leftists — beer-can-crushing lesbians who threaten to beat Ignatius to a pulp, males who emit an “emasculated version of an Apache war cry” when he unplugs a phonograph playing Lena Horne.

I realize that I’ve been using “reactionary” here mainly as a dirty word. Yet perhaps because Toole committed suicide at some point after completing this novel, and because it’s virtually impossible to imagine an Ignatius free of his hangups, and because I’m writing this during an insufferable heat wave lacking both theology and geometry, when flesh seems heavier and weaker than ever, I can’t help but wonder if the unexpected triumph of liberalism at the novel’s conclusion is the right ending for this book to have. I can’t quite believe it.

The dreaded Myrna arrives in the nick of time to shuttle Ignatius out of the state in her car. The end that I’d anticipated was much more quixotic and bleak: Ignatius undergoing shock treatments (which is literally the fate that Myrna saves him from, after his mother, now engaged to Robichaux, is persuaded by a friend to phone the hospital). This would have been decidedly less Yankee-contemporary and more Southern-medieval in flavor, like submitting Quixote to the Spanish Inquisition. But A Confederacy of Dunces was written in more hopeful times than these. And Toole was moved to give Ignatius another improbable chance — a gesture he regrettably failed to make on his own behalf.

— The Soho News, August 27, 1980