Slightly tweaked from its original appearance in the Autumn 1975 issue of Sight and Sound. — J.R.

Nashville

‘A dialectic collage of unreality,’ remarked pop singer Brenda Lee, emerging from the Nashville premiere in August. After a summer full of humourless rhetoric in the American press about ‘the true lesson of ‘Watergate’, ‘the failure of our civilization,’ ‘the long nauseating terror of a fall through the existential void,’ and equally grave matters — most of it implying that a movie has to be about ‘everything’ (i.e., the State of the Union) before it can be about anything — it was refreshing to discover that someone, at long last, had finally got it right. Even if Lee’s comment was intended as a slam, it deserves to be resurrected as a tribute. For if Nashville is conceivably the most exciting commercial American movie in years, this is first of all because of what it constructs, not what it exposes.

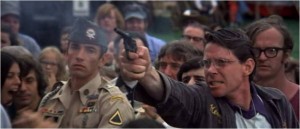

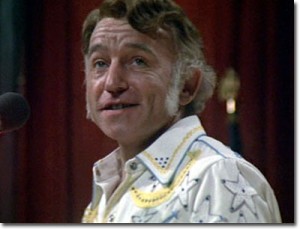

From the moment we begin with an ad for the film itself — a blaring overload of multi-media confusion — and pass to a political campaign van spouting banalities, then to a recording studio where country music star Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) is cutting a hilariously glib Bicentennial anthem, Nashville registers as a double-fisted satire of its chosen terrain, and it would be wrong to suggest that its targets of derision are beside the point, even if the angle of vision subsequently widens to take in more than just foolishness. But a rich ‘dialectic collage’ of contradictory attitudes and diverse realities is what brings the film so vibrantly to life, and to launch moralistic rockets on such a shifting base is to miss its achievement entirely. In point of fact, the film celebrates as much as it ridicules — often doing both at the same time — while giving both its brilliant cast and its audience too much elbow room to allow for any overriding thesis.

Robert Altman and his collaborators have built a narrative out of many superimposed parts, and it is worth looking at some of their procedures. Joan Tewkesbury wrote her blueprint-script after spending only five days in the Tennessee capital, apparently guided mainly by Altman’s request that its country music milieu be linked comparatively to politics, and, that an assassination figure at the end. Actors were given the choice of following her dialogue or substituting their own, and many were invited to compose their own songs (usually with Richard Baskin) under the (questionable) assumption that country music, like politics, is potentially anyone’s game. Similarly, Thomas Hal Phillips was given the job of launching a presidential primary campaign — the film is set in 1976, the year of the U.S. Bicentennial — for an invisible fictional candidate named Hal Phillips Walker, complete with local headquarters and a Replacement Party platform to be heard from a van, prowling the streets ignored like a ghostly proxy. Finally, the sound system inaugurated on California Split — a set-up using many on and off-screen microphones whose volume levels can be altered during the sound-mixing stage — enabled Altman to extend his principles of improvisation further, beyond the parameters of the camera’s range.

A great deal was shot — two hours of rushes were reportedly screened every day — and at one stage Altman considered releasing two mammoth films, each of which would cover the same time span while concentrating on twelve different characters. [Postscript: he also considered and planned — but unfortunately never followed through on — a TV miniseries.] That he settled on a more conventional solution, and concludes the film with a veritable surplus of Significance after over 150 minutes of open sailing, is of course commensurate with the querulous sociological responses. But prior to this capitulation he engenders his most adventurous structure to date, deftly juggling his cast of two dozen characters with the assurance of a master storyteller while simultaneously demanding (and rewarding) an unusual amount of alertness and participation from the spectator.

Quite simply because he has reinvented Nashville rather than discovered it, even the most spontaneous and wayward elements in his s-f fantasy remain firmly within his grasp. Starting with the campaign van, Hamilton with his mistress (Barbara Baxley) and son (Dave Peel) and musicians, an English groupie-interviewer named Opal (Geraldine Chaplin), a black gospel group with white lead- singer Linnea (Lily Tomlin) — and leaving it partially up to the viewer to decide on the relative importance of each, to discriminate between characters and extras (a task not unlike that faced by most of the film’s inhabitants) — Altman proceeds to shuffle these mini-plots while casually adding fourteen characters more, as everyone but Opal and Linnea appears or reappears at the airport; then deals them out in orderly succession as they leave the parking lot, finally assuming a recognizable narrative shape; and scrambles most of them again when they become caught in a freakish highway pile-up, to be joined by Linnea, Opal and others.

One proceeds through this constant play between organization and chaos as though in a mystery, picking out threads that may be either loose ends or clues to future events — an aspect that makes Nashville well worth repeated visits. Cutting between the fatuous affirmations of Hamilton’s song (‘We must be doin’ somethin’ right to last 200 years’) and the more unbridled ones of the gospel group establishes one kind of contrast, but when Opal starts prattling over the sound of the latter about ‘darkest Africa, and ‘naked frenzied bodies,’ our attention and response become further subdivided. Similarly, when she is holding forth about American violence during the traffic jam, what’s funny isn’t merely the delivery of her hysterical clichés in medium shot and screen center, but the relationship between that and the sheer irrelevancy of a little boy outside the car in left foreground, simultaneously consuming an ice-cream cone like a detail out of Tati or Brueghel.

With the recurring juxtapositions of performers with spectators, insiders (Timothy Brown, Allan Nicholls, Cristina Raines) with outsiders (Robert Doqui, David Hayward, Bert Remsen), contrasts between public and private behavior frequently come to the fore — epitomized by Connie White (Karen Black) trying on a variety of smiles while waiting to appear on the Opryland stage — and deceptions involving telephones become a minor leitmotif. If Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakley) is the only character who seems incapable or such duplicity, this may not be unrelated to her climactic ‘breakdown’ during a concert, which hinges on a lack of separation between private and public identities. Clearly the most professional of the singers, whose songs are least mediated by any sort of irony in their presentation, she is also the one who abandons herself most nakedly in her performances.

That she turns out to be the assassin’s target seems to square with Altman’s taste for cosmic injustice — formerly evidenced by the death of the hero in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, the Coke bottle victim in The Long Goodbye, and, equally present here in the sudden irrelevant speech of Pfc. Kelly (Scott Glenn) to Mr. Green (Keenan Wynn) just after the latter has learned of his wife’s death; cruelly twisting the screw, Altman cuts from his strangled sobs to the laughter of Opal and Triplette (Michael Murphy) in another scene, as if to underline the isolation of his grief. And to compound the sense of absurdity, it is Green’s angry departure from his wife’s funeral in search of his groupie niece (Shelley Duvall) that indirectly causes the assassination to take place.

Some characters — Duvall, David Arkin’s chauffeur, ]eff Goldblum’s magician –are static figures to be brought on like running gags; Opal and Tom (Keith Carradine) are more diversified versions of the same principle. But others are subject to development, elucidation and modification, either in their behavior or in the way they are presented. Linnea, whom we learn to identify with humane impulses, is briefly seen at Hamilton’s party describing the results of various traffic injuries with apparent relish; Hamilton’s son, bashful and courteous at the same party, becomes a drunken lout at the fund-raising campaign smoker where Sueleen (Gwen Welles) does a striptease, while Sueleen herself shifts during this scene from a comic character to a tragic one. And after driving Sueleen home, Linnea’s cuckolded husband (Ned Beatty) suddenly launches a clumsy seduction attempt of his own.

Alongside these uncertainties about characters are ambiguities involving events. The film offers evidence but no final proof about which of Tom’s four ladies he dedicates his new song to; and we may wonder whether Barbara Jean’s behavior at her concert actually constitutes a breakdown — or if it does, whether this is partially provoked by her husband (Allen Garfield) forcing her off the stage. We don’t know if she dies after being shot at the political rally or why, indeed, she is shot at all.

Does Opal work for the BBC? She repeatedly claims she does, and most reviewers have followed her lead, often going on to criticize the part in those terms. But if Opal’s scene with Triplette had included more of the original footage, in which she admits that she doesn’t work for the BBC, her character would have been assigned another label, and in each subsequent scene would have registered differently. Multiplying this detail by twenty-four, one easily sees why the film should have been much longer, and how extensively our chancy and partial experience of it is a response to work in progress, the unfolding of a narrative complex rather than its ultimate destination. Thus to stop the movie at a precise meaning — and worse yet, a sociopolitical one– is to rob it of its complexity and consign it to the same dustbin of platitudes that Opal and Hal Phillips Walker both specialize in accumulating.

Not that Altman is entirely blameless in eliciting such a misplaced impulse. Nashville begins with a crowd of actors-as-extras — inviting us to ramble like tourists over the busy landscape, picking our own points of entry, our mixtures and degrees of interest — and ends with a crowd of extras-as-documentary-subjects, obliging us to accept them as emblems of some higher order, with the Nashville Parthenon and three screen-filling shots of the American flag to point the way. The camera zooms back to take in the entire spectacle of crowd, edifice and flag, yet the effect is constricting rather than expansive — a world of diverse possibilities shrunk to the dimensions of a Statement and platitude. Then another, recorded version of ‘It Don’t Worry Me’, the emblematic theme song with which Barbara Harris’ aspiring singer has lulled the crowd and forged her own unexpected ascendancy to stardom, is heard over the final credits, neatly balancing the film’s hard-sell introduction, which also suggested the abstracting of a complex into a commodity. Acknowledging itself as a piece of merchandise, complete with packaging, price tag and succinct catalogue description, Nashville leaps from its exciting and individual state of grace — the open process of its initial making, and the better part of its unraveling — into the limited vocabulary and closed circuits of a public forum.*

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

* Much of the tenor and form of this piece undoubtedly stemmed from two factors that may be worth stressing: it was written in London, where I was witnessing other American responses from afar, and I was determined to mention all twenty-four actors in the review. [2002]