This is the first of all my Paris Journals for Film Comment, written for their Fall 1971 issue, and also the first piece I ever published in that magazine, when it was still a quarterly. This Journal is missing only its first section — a somewhat misinformed and misconstrued account of an ongoing feud at the time between Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif that I see little point in recycling now. (I’ve corrected a few errors here, but also left in a few others — such as the running time and title of OUT 1 — to preserve some period flavor.) I wound up writing this column for virtually every issue of the magazine, which soon afterwards became a bimonthly, for my remaining three years in Paris, then transformed it into a London Journal during my two and a half years in the U.K., and finally turned it into a column called “Moving” for a brief spell after I moved back to the United States in early 1977. (If memory serves, the last of the “Moving” columns became the prelude to my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, published by Harper & Row in 1980.) —J.R.

Paris Journal

Note for harassed filmographers and auteur critics: Now that many leading French directors are helping to make ends meet by directing publicité films – ads used in movie theaters and/or on television -– a list of who has made what might be useful, particularly since most of these works are unsigned. For the record, then, Georges Franju has worked for Aspro (a brand of aspirin), William Klein for Dim socks and stockings, Jacques Tati for Gervais ice cream, Jean-Luc Godard for Schick razors, and Robert Dhéry for something called Vapona. Unfortunately, my research hasn’t uncovered the products handled by Claude Lelouch or Louis Malle — or by Stanley Kubrick and John Schlesinger, who are shooting commercials abroad – but I can suggest one possible area for critical investigation: the use of primary colors in Klein’s ELDRIDGE CLEAVER and his ad for Dim, and how these relate to one another.

***

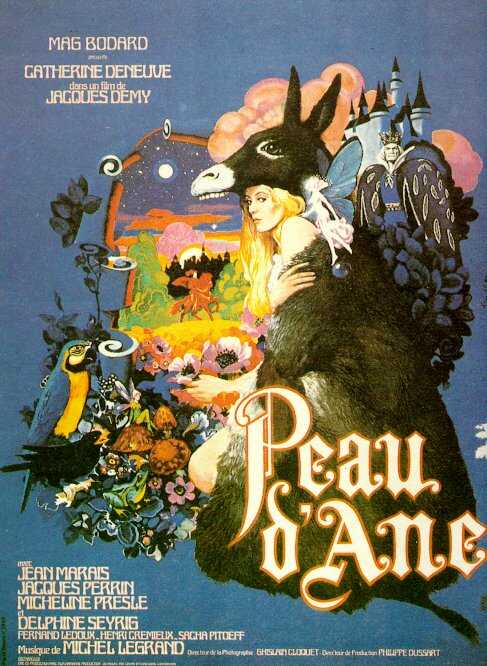

Jacques Demy’s PEAU D’ANE: If I may be forgiven some hyperbole, Jacques Demy’s newest movie resembles an unholy marriage between Cocteau’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST without the beast and Tashlin’s CINDERFELLA without Jerry Lewis. That is to say, all its childhood dreams are purged of everything which might be called marvelous or frightening or even cumbersome, and one is left with interior decoration — a mural of legends that no one can believe in. Taking a fairy tale from Charles Perrault that includes magic, incest, a seductive witch, and a frog-spitting crone, Demy has ironed out most of the potential anxiety with the help of such pacifiers as Catherine Deneuve (the princess), Jacques Perrin (the prince), and Michel Legrand (the score), all three of whom worked to similar effect in THE YOUNG GIRLS OF ROCHEFORT. As with Life Savers, the colors come in all fruity flavors — extras and odd parts of the décor are painted blue or red to match their corresponding kingdoms — but the aftertaste is bitter with melancholia. In a “specialty” number, Deneuve sings a recipe for a magic cake to her alter ego who prepares it, and the tried brown lump that comes out of the hearth is the sad equivalent to Demy’s achievement.

A host of invocations to the muse of Cocteau, which include everything from Jean Marais to direct quotation, creates at best the fantasy of a film, not a film of a fantasy. For the unassuming kid who doesn’t know or care who Jacques Demy is and wants an honest fairy tale, PEAU D’ANE is likely to come across as something of a cheat. For the rest of us, I suppose the film is something that one can brood over, in classic decadent fashion. PEAU D’ANE (“Donkey Skin”) aspires to a brand of romanticism that is no longer being manufactured because it is no longer believed in. Like Jim McBride’s GLEN AND RANDA, it is about the death of Wonder Woman, but unlike GLEN AND RANDA, it didn’t make me want to cry. It’s too stiff-necked and over-starched to look down into its own abysses, and when Demy coyly introduces a telephone, a hash pipe, and a helicopter into his “fairy kingdom,” it is no violation at all, for that kingdom has never begun to breathe on its own. Godard faced a comparable dilemma in UNE FEMME EST UNE FEMME when he tried to make a “neo-realist musical,” and viewers who find some emotional solace in that frigid film may want to crawl around in Demy’s refrigerator as well. They’ll find a number of wonderfully processed and packaged products inside: Deneuve-Perrin for the main course, Marais and Delphine Seyrig (the fairy-witch) as elegant side dishes, and a rich overlay of Legrand music for digestive purposes. But they might find it worthwhile to consider how much of the food ever gets cooked or eaten, and how much remains locked forever in cold, plastic-vegetable possibility.

***

A versatile, not easily classifiable young French director who deserves wider recognition, Jean-Daniel Pollet has already directed an unwieldy number of hard-to-see films in the past few years. Having seen only 3 shorts and 2 features, I cannot pretend to give a comprehensive account of his work, but the evidence of LE HORLA and L’AMOUR C’EST GAI, L’AMOUR C’EST TRISTE suggests that there is much to be discovered.

Within its tightly filled half-hour, LE HORLA (1966) offers some interesting strategies for adapting a literary work. Pollet has indicated in an interview that his interest in the project was not so much De Maupassant’s horror story itself but the problem of integrating the text into a cinematic structure. Part of his solution is to maintain a fluid continuity in the spoken first-person narration while locating this discourse through montage in three alternating “relative” tenses: past (the plot unfolding beneath the narration), present (the narrator recounting the action into a tape recorder), and future (the tape recorder playing his voice in an abandoned rowboat). Thus while the story’s chronology and continuity are respected, the montage enables the film to achieve a semi-autonomous achronological structure of its own, and the tensions between these coexisting forms produces some extraordinary effects — effects, moreover, which serve the original story admirably, enclosing its intimations of possession and madness in a rigid continuum of haunting finality. Equally striking is a bold thematic use of color, with the richest blues this side of PIERROT LE FOU.

If the above summary suggests that Pollet is something of a purist (a description borne out by his remarkable short feature MEDITERRANÉE), the broad, loose proletarian comedy of his third feature, L’AMOUR C’EST GAI, L’AMOUR C’EST TRISTE (made 1968, but released only this year), denotes a wholly different manner: the title perfectly describes the film’s mood and ambition. Substantially served by the morose, gentle ambience of Claude Melki, who may be recalled from Melki’s episode in PARIS VUS PAR…, the comedy is mainly restricted to the quiet agonies of a tailor too naïve to realize that his sister is a prostitute and too shy to declare his love for a girl from the provinces who shares his room. With virtually all of the action contained in a single two-room flat that is smoothly traversed by lateral tracking shots, this fragile material is kept afloat by sheer craftsmanship and a Molièresque rendering of social behavior. There’s a very touching cameo appearance by Marcel Dalio — a ubiquitous, irrepressible trouper now in his seventies — and a sweet, non-assuming sense throughout of staying within modest boundaries that firmly places the film in what Manny Farber calls the termite range.

***

Georges Franju’s LA FAUTE DE L’ABBÉ MOURET: After observing the cold brilliance of THOMAS L’IMPOSTEUR only recently, it is depressing to discover that Franju is capable of such flat, undistinguished work as his latest film. Without having read the Zola novel from which this was taken, I cannot give an adequate explanation of how or why the source has been betrayed. The anti-Catholicism of earlier Franju films is certainly not muted here, but its expression is trivialized by so many village-atheist conceits that one looks in vain for the subtlety and irony that underlines his previous efforts. The middle section of the film, chronicling a romantic idyll between an abbot suffering amnesia and a golden-haired ingenue, is every bit as restrained as ELVIRA MADIGAN crossed with Zeffirelli’s ROMEO AND JULIET. One brief, stunning Franjuvian moment occurs when the abbot is lifting a statue out of a crate, and the framing of the shot, by eliminating his hands, turns the movement into a magical ascension of the Virgin out of excelsior. The rest, unfortunately, is pretty heavy going.

***

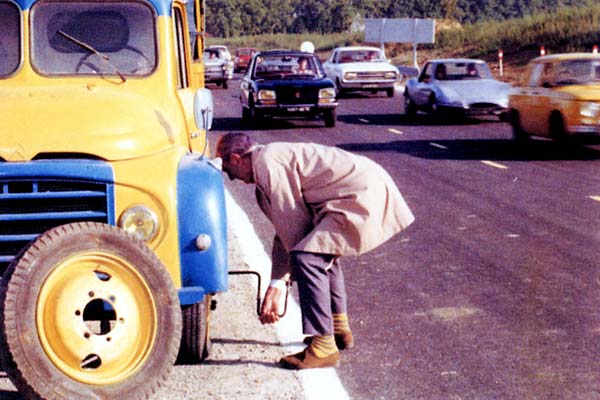

Jacques Tati’s TRAFIC: Being one of the few moviegoers in the Western Hemisphere who considers PLAYTIME (1967) a masterpiece — a truly innovative film whose continued absence in America creates a serious cultural gap — I approached his newest movie with fervid hopes and a fair amount of trepidation. Would the commercial disaster of the previous film goad Tati into a stylistic retreat, an attempt to regain the audience who flocked to MON ONCLE (1958)? Would the more modest budget of TRAFIC — only his fifth film in 24 years — result in a safer, more conventional vehicle for M. Hulot, the quaint middleclass bumbler? I’m afraid it did.

Obviously Tati is too accomplished and intransigent a filmmaker to be capable of selling himself down the river, and there is much in TRAFIC to be grateful for: a rigorously composed soundtrack of remarkable density, some wonderfully sustained and developed gags, and a sense of contemporary French manners and moods that few directors could equal. Following the frustrated progress of a car designer (Hulot) with his cohorts and display model from Paris to an auto exposition in Amsterdam, Tati shapes his plot around all the irritations of motorized travel — breakdowns, smashups, traffic jams, customs inspectors — as well as the rituals and gimmicks inherent in promoting cars. Despite a predictable amount of hackneyed material, there is an agreeable freshness in much of the execution, and certainly no one could accuse Tati of stretching a Pete Smith Specialty out to feature length. But after the extraordinary ambitiousness of his last film, the horizons of TRAFFIC seem pretty low, and one suspects that Tati is mainly biding his time.

PLAYTIME tended to alienate audiences by eschewing sex and violence, plodding along at a lifelike and undramatic pace, and cramming the 70mm screen with so many different things to watch at once that the average shot resembled a multiple choice question (where is the next gag likeliest to erupt?). The off-center timing of several gags compounded this alienation, particularly for those expecting the Pavlovian disciplines and guidelines of the Sennett-Keaton-Chaplin school. Much in TRAFIC seems to work consciously against these tendencies: there is “sex” (a simpering glamor doll in charge of public relations played by Maria Kimberly, who becomes more of a “star” in the traveling group than the car itself); there is “violence” (a multiple freak accident as extravagant as anything in WEEKEND); the pace is relatively clipped; and most of the gags are preselected and framed for immediate consumption. If TRAFIC works more successfully with audiences — and it seemed to, judging from the laughter both times I saw it — this is probably because it does most of the work for them. There is still enough of Tati’s quirky habits of selection to create some discomfort — how can one respond to a director who finds virtually everything funny, except to embrace this notion uncritically or run away from it in disgust? — but not enough to support a radical vision.

All the Kafkaesque ordeals of the spectators of PLAYTIME were precisely the same as those of the characters — tourists wandering aimlessly through interchangeable buildings of glass and steel — but when Tati brought all his characters together and made them friends, he infused the same landscapes with beauty and awe, making them rich with possibilities. By turning Hulot into another lost wanderer, exempted from his role of “leading” the audience, Tati compelled anyone willing to play his game to discover a new way of looking. TRAFIC — like MON ONCLE, minus its unconvincing upbeat ending — begins and concludes as a catalog of gripes, and teaches us essentially nothing that we don’t already know. Only a few stray moments (lunch with an easygoing Dutch mechanic near a peaceful canal, brief images of Apollo II glimpsed on TV) suggest any way out of the terrors the complaints imply, and little force is felt behind them. Most of the film is concerned with hurry, impatience, and indifference — a lot of angry vibes about very little — and even Hulot himself occasionally contributes to the bad feeling. The irony is how easily a bemused public will choose this simple pessimism –a prosaic string of bead-like gags — over the complex and poetic optimism that preceded it.

***

Postscript: Recent news that Jacques Rivette’s 14-hour film, OUT ONE, is now completed gives us a lot to look forward to in more ways than one. A partial adaptation of Balzac’s Histoire des treize trilogy in a contemporary setting, the film will be split up into episodes to compose a TV serial, while another 2-hour version will be put together for general release. Having just seen the 4-hour version of L’AMOUR FOU (1968) for the first time, I can only regret that OUT ONE will probably not be available to many audiences in its original form. The earlier film, which parallels and bypasses much of Warhol’s research (in FUCK/BLUE MOVIE and other films) in giving precise framings to random bug-like actions and lifelike durations, is also compelling for its dialectical use of 16 and 35mm footage, each of which approaches and contains the action in a different way, and its additional unforced dialectic between acting (continuing rehearsals for a production of Andromaque) and living (the fluctuating relationship between the play’s director and his mad, despairing wife). Although I haven’t seen the 2-hour version of L’AMOUR FOU, I find it hard to imagine that it could be half as rich or absorbing as the longer one. To spend 257 minutes watching the same people provokes an intimacy and involvement that is qualitatively different from the experience of most films; curiously enough, it is less exhausting.

—Film Comment, Fall 1971; partially corrected and slightly edited, September 2009