The following was written for the Monthly Film Bulletin — a publication of the British Film Institute, where I was serving at the time as assistant editor — and it follows most of the format of that magazine by following credits (abbreviated here) with first a one-paragraph synopsis and then a one-paragraph review. (For his resourceful photo research, thanks once again to Ehsan Khoshbakht.)–J.R.

Black and Tan

U.S.A., 1929

Director: Dudley Murphy

Dist—TCB. p.c—RKO. p. sup—Dick Currier. sc—Dudley Murphy. ph—Dal Clawson. ed—Russell G. Shields. a.d—Ernest Feglé. m/songs—“Black and Tan Fantasy” by James “Bubber” Miley, Duke Ellington, “The Duke Steps Out”, “Black Beauty”, “Cotton Club Stomp”, “Hot Feet”, “Same Train” by Duke Ellington, performed by—Duke Ellington and His Cotton Club Orchestra: Arthur Whetsol, Freddy Jenkins, Cootie Williams (trumpets), Barney Bigard (clarinet), Johnny Hodges (alto sax), Harry Carney (baritone sax), Joe Nanton (trombone), Fred Guy (banjo), Wellman Braud (bass), Sonny Greer (drums), Duke Ellington (piano), (on “Same Train”, “Black and Tan Fantasy”) The Hall Johnson Choir. sd. rec—Carl Dreher. with—Duke Ellington and His Cotton Club Orchestra, Fredi Washington, The Hall Johnson Choir. 683 ft. 19 min. (19 mm).

Duke Ellington rehearses his “Black and Tan Fantasy” for a club date in his flat with trumpet Arthur Whetsol until interrupted by two men from the piano company, sent to remove the instrument because he has fallen behind in the payments. Dancer Fredi Washington bribes the movers with a bottle of gin into telling their boss that no one was home. Duke tells Fredi that they can’t take the job at the club because of her heart condition, but despite her faintness, which causes her to see multiple images, she insists on performing her dance and collapses at the end of her number. A chorus of other dancers is brought on, but Duke stops their band in the middle of their tune so that he and his men can stand by Fredi on her deathbed. There, at her request, they play the “Black and Tan Fantasy” as she loses consciousness.

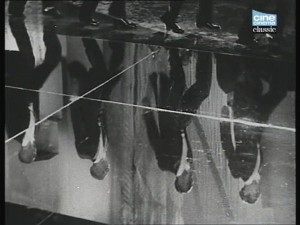

Dramatic films which use jazz organically (To Have and Have Not is a supreme example) are few and far between, while jazz films which feature the music dramatically are perhaps even rarer. The singularity of Black and Tan, which comprises the first appearance of Duke Ellington on film, is that it fuses both categories — developing a sort of poetic synthesis in less than twenty minutes that, while clearly awkward and dated in many of its ingredients, nevertheless demonstrates, at the very onset of the sound period, that the two new arts of the 20th century don’t necessarily have to trample on one another. Written and directed by Dudley Murphy, who made a short with Bessie Smith (St. Louis Blues) earlier the same year –- apparently with some of the same sets and uncredited bit players –- and previously executed Fernand Léger’s ideas in Ballet mécanique, Black and Tan uses arty trappings and a creaky plot, but has a sharp enough sense of form to turn both of these liabilities into assets. After the title tune is presented embryonically in rehearsal — unfortunately without the participation of Bubber Miley, the remarkable trumpeter who played a substantial role in Ellington’s early conceptions, but well-performed by Arthur Whetsol in the Miley manner — the action is temporarily pre-empted by some low comedy involving the piano movers, racist stereotypes with a surreal, inventive use of language (“Bro-ther, re-move yuh anatomy from that mahogany”, one announces to Ellington, remarking that he hasn’t paid anything on it since last “Octuary”; his jockey-sized sidekick is variously called “Action”, “Sarasparilla”, and “Eczema”). But this is quickly bypassed when the scene shifts to the club, where two eerie dances are performed by five men of ascending height in tuxedos, making strict linear formations on a mirror-like floor while the Ellington band plays behind them. Even more strangely, when the point of view shifts to Fredi Washington, the first number is repeated precisely, immediately upsetting one’s sense of linear time, while one’s visual bearings are confused by the splitting up of the musicians and already duplicated dancers into a myriad mosaic. By the time Washington has made her own entrance and gone into her wild shimmying number, the mood and music have both turned fairly demonic, and a sudden shot of her gyrations from beneath the glass floor, echoing L’entr’acte, increases the dislocation. Soon afterwards, the scene shifts once again to her death chamber, where the chiaroscuro effects, compression of space (the entire Ellington band and Hall Johnson Choir appear to be crowded around her bed, and silhouetted on the far wall), and powerful, relentless thumping of Wellman Braud’s bass heard against the ensemble on “Same Train” are so extreme that the effect is truly unsettling. When the assemblage goes into a “full-dress” version of the title tune at her dying request — complete with solos on trumpet, trombone, and Bigard’s piercing clarinet — the spare, growling blues with which the film began, which literally quotes the famous “Funeral March” from a Chopin piano sonata in the fifth and sixth bars, and again the eleventh and twelfth, has grown into a Dionysian lament. Assuming once again Washington’s viewpoint, the camera focuses on Ellington in an image that gradually blurs, like a guttering candle. Then she dies, and the camera cuts to the last and most disturbing image — another blurred shot of Ellington that is no longer justified by Washington’s viewpoint, thereby collapsing the film’s co-ordinates of space as well as time into the realm of pure idea, or pure music; and both slowly fade away in the same flickering breath.

— Monthly Film Bulletin, vol. 43, no. 510, July 1976