This essay — commissioned originally in the mid-1990s by Alexander Horwath for a collection in German published by the Viennale, and later published in 2004 by the Amsterdam University Press as The Last Great American Picture Show: New Hollywood Cinema of the 1970s, coedited by Thomas Elsaesser, Alexander Horwath, and Noel King — overlaps with various other pieces of mine, and is obviously out of date in some of its details, but it seems worth reprinting for some of the arguments it draws together. And it’s been fun hunting up illustrations for it on the Internet. — J.R.

“New Hollywood” and the 60s Melting Pot

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Let me begin with a few printed artifacts, all of them from New York in the early 60s: two successive issues of the NY Film Bulletin published in early 1962, special numbers devoted to Last Year at Marienbad and François Truffaut; and three successive issues of Film Culture, dated winter 1962, winter 1962-63, and spring 1963. Cheaply printed but copiously illustrated, the two special numbers of the NY Film Bulletin are the 43rd and 44th issues of a monthly, respectively twenty and twenty-eight pages in length. The Last Year at Marienbad issue consists exclusively of interviews with Alain Resnais, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and editor Henri Colpi, all translated from French magazines, and a briefly annotated Resnais filmography. The Truffaut issue — apart from a translation of Truffaut’s André Bazin obituary from Cahiers du Cinéma, brief script extracts from Shoot the Piano Player and Jules and Jim, and a Truffaut filmography — contains all new material: articles on Shoot the Piano Player by the magazine’s editors Marshall Lewis and Andrew Sarris and its publisher R.M. Franchi, and a ten-page interview with Truffaut by Franchi and Lewis. In Film Culture no. 26, eighty pages long, articles on Preston Sturges (by Manny Farber and others), Frank Tashlin, and Vincente Minnelli’s Two Weeks in Another Town (the latter two by Peter Bogdanovich) rub shoulders with with a translation of the “scenario” (i.e., treatment) of Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa Vie, P. Adams Sitney writing about Stan Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night and Prelude, two statements by experimental animator Robert Breer, an interview with Soviet director Grigori Chukhrai, and an article about L’Avventura, La Dolce Vita, and Breathless, among other pieces; on the cover is a reproduction of the opening title of Orson Welles’s Mr. Arkadin. No. 27, in addition to featuring Farber again (this time on “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art”), includes Sarris’s “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Pauline Kael on Shoot the Piano Player, Jack Smith on “The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez,” Gregory Markopoulos on Ron Rice, more material on Breer, and a special section on Welles’s celebrated 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast. And sixty-seven of the ninety-six pages of No. 28 are devoted to Sarris’s soon-to-be-notorious and highly influential “The American Cinema,” later to be expanded into a book.

The point of these summaries is to give some notion of the kind of heady mix that was integral to American film culture during this period — a period when, for better and for worse, there was still only one film culture, however charged with controversy and disagreements that culture might have been. The rapid growth of academic film studies was still not to come for about another decade, and the even more dizzying changes brought about by the distribution of movies on videotape and the quantum leaps in promotion for big-studio product were even further away. At this stage, there were only a vast number of movies of different kinds being made, written about, and debated, often in the pages of the same magazines.

Though something resembling the same mix was evident in England around the same time, in the pages of such alternative film journals as Motion and Movie — without the American avant-garde, one might add, but with a similar kind of interfacing between Hollywood and continental art films — the most salient difference was that in the United States, at least, a multifaceted redefinition of the American cinema was fully in progress that involved not only a reconsideration of what it had been, but also a great deal of thought about what it might be.

Unlike the relatively staid pluralism of more established Anglo-American film journals during this period, such as Film Quarterly and Sight and Sound — which were also reflecting some of the changes that were taking place in film culture, but without celebrating them all in quite so partisan a fashion — these magazines were basically giving vent to minority positions, and a central aspect of those positions was a broadening of the usual definitions of what constituted art in movies. Within the mainstream press of both England and the U.S., Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks were still regarded as frivolous entertainers and nothing more while the models of respectable American art films generally entailed solemn treatments of weighty subjects without the “intrusions” of personal, directorial styles (Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg might stand as the locus classicus of this position). Meanwhile, the American underground — despite the recent splashes made by the first features of John Cassavetes (Shadows) and Shirley Clarke (The Connection) —- was mainly regarded as marginal and parochial; Dwight Macdonald wrote sympathetically about both of these films in Esquire, a national mainstream publication, but was hostile to most other manifestations of the movement, such as Jonas Mekas’s Guns of the Trees, and he completely (and characteristically) ignored such figures as Brakhage, Markopoulos, Breer, and Rice.

Among the key revelations to be found in these magazines were Resnais’s enthusiasm for such Hollywood pictures as Singin’ in the Rain and Suspicion and Truffaut’s buried references to Hitchcock, William Saroyan, Rossellini, Lola Montez, and the Marx Brothers in Shoot the Piano Player (as signaled by Sarris). But it also was quickly becoming apparent that the multiple references to Hollywood in so-called New Wave pictures from France — the recreated sequence from Gilda and the life-size cutout of Hitchcock in Marienbad, the references to Bogart and Boetticher and Samuel Fuller’s Forty Guns in Breathless — were beginning to be matched by evocations of European art films in certain Hollywood movies as well: the parodic nods to both La Dolce Vita and Marienbad in the party scenes of Two Weeks in Another Town, for instance, or the disorienting shifts between genres in The Manchurian Candidate, which created much the same sort of critical confusion and controversy as the comparable shifts in Shoot the Piano Player — though, to the best of my knowledge, critics showed little if any awareness of this latter similarity at the time, including such rare champions of both films as Pauline Kael. For Kael, “the closest an American movie has come to the constantly surprising mixture in Shoot the Piano Player” was Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H, released eight years later.

It’s important to stress that the readership of such magazines as the NY Film Bulletin and Film Culture were extremely limited and, with few exceptions, local; copies could be found in a few specialised bookshops in Manhattan, but seldom anywhere else. Moreover, the foreign and experimental films that were written about in such magazines often had a circulation that was just as limited; foreign films that fared poorly at the box office in New York were unlikely to turn up in other cities, and apart from a handful of outposts in the rest of the country, most experimental films had limited screenings even in New York, and were likely to turn up elsewhere, if at all, only several months or even years later. Consequently, though some Hollywood directors would have been able to see some of the better known French New Wave movies of this period — e.g., Last Year at Marienbad and Jules and Jim, but not Paris Nous Appartient or Les bonnes femmes — the odds of them seeing films by Stan Brakhage or Robert Breer were relatively slim.

Consequently, in order to discuss the formal and stylistic influence of European art films and American experimental films on Hollywood filmmakers of the 60s and early 70s, it is difficult to postulate any direct lineages in any but a few exceptional cases. We know, for example, that Dennis Hopper, partially as a result of his connections with the world of contemporary painting, sculpture, and photography, was familiar with some of the experimental works of Bruce Connor and Andy Warhol (among others) when he was making Easy Rider (1969) and The Last Movie (1971), and that he even made one or more (undocumented) experimental shorts himself prior to these features. Similarly, we can be fairly confident that when Martin Scorsese was directing Taxi Driver several years later, he had seen Michael Snow’s Wavelength and Back and Forth and Godard’s 2 ou 3 Choses que je sais d’elle — though it is crucial to bear in mind that Taxi Driver was made in New York and that Scorsese routinely sees many films that most of his Hollywood colleagues would never have even heard of.

But in order to speak of European or American avant-garde filmmaking making a dent on Hollywood — even during one of the few periods of this century when the U.S. was relatively open to outside cultural influences — it becomes necessary to postulate many intervening forces and way stations, and to acknowledge that any comprehensive account of such influences would have to draw on a detailed exhibition history that has never been written and almost certainly never will be. Indeed, before one even attempts to sketch such an account, four methodological obstacles should be cited at the outset:

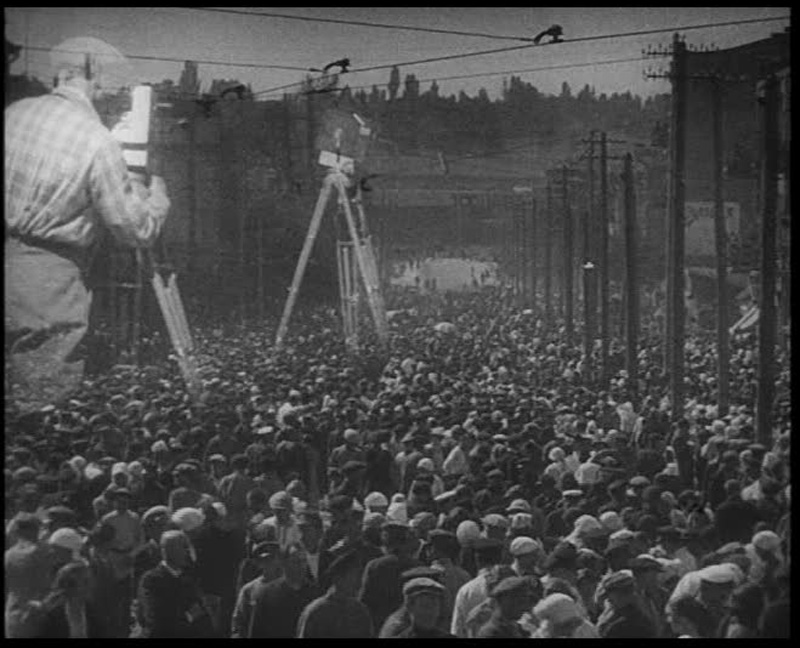

(1) The issue of direct or indirect influence is often much more complex than many critics prefer to believe. Direct imitation or citation tends to be acknowledged much more readily than any less obvious assimilation or application of influence, which generally shows more thoughtfulness and creativity on the part of the filmmaker. One case in point might be the example of Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock (1970), arguably the greatest of all American documentaries made during the 60s and early 70s. On the face of it, Woodstock bears no trace of any direct influence from either vanguard European or American underground filmmaking of the same period. Yet because the French New Wave inspired an international generation of filmmakers to draw more freely and widely from the pool of techniques available from film history, including the silent film — as evidenced by, say, the use of the iris in Breathless and the uses of masking in Shoot the Piano Player and Jules and Jim — it is certainly possible that Wadleigh could have been inspired by their example to draw liberally from the techniques of the great city films of the 20s, works such as King Vidor’s The Crowd, Paul Fejos’s Lonesome, F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise, Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a Great City, and Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera. (Significantly, Vidor himself expressed admiration for the drama and spectacle of Woodstock’s rainstorm sequence; and if Wadleigh’s own “city” consisted of some 400,000 young people camped out in a New York pasture, it seems entirely possible that his superimpositions, split-screen framings, and diverse forms of associative and rhythmic editing all stemmed directly or indirectly from the strategies of late silent films in dealing with the multiplicity and energy of urban crowds.)

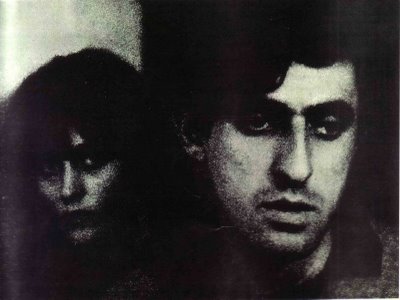

(2) An astonishing number of influential and/or pertinent American independent films of the early 60s have been virtually forgotten and lost to history, at least if one relies on most “standard” written accounts. To an alarming extent, contemporary academic studies of this subject in the U.S. essentially recycle the titles already found in a small number of books and journals and make little effort to move beyond them. Thus in order to be aware of the major contemporary impact made by Peter Emanuel Goldman’s New York independent feature Echoes of Silence (1965) [see below] or the fact that future Hollywood filmmakers John Milius and George Lucas made experimental short films as students at the University of Southern California during the 60s, it virtually becomes necessary to refer to personal experiences rather than printed sources. In the case of Goldman’s film, I can refer to my own experiences, having seen Echoes of Silence in New York during the mid-60s and read about it in many New York publications at the time; in the case of Milius’s and Lucas’s early work — or the early experimental work of Hopper mentioned above — I have to depend on the memories of a west coast colleague and filmmaker, Thom Andersen, who was a film student at the University of Southern California at the same time as Milius and Lucas, and saw some of Hopper’s early work in Los Angeles during the same period. Characteristically, neither Goldman’s name nor this information about Hopper, Milius, and Lucas can be found in such supposedly “definitive” reference works as P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde 1943–1978 or David E. James’s more recent Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties, and these are only four examples of routine omissions that could undoubtedly be counted in the hundreds.

(3) By and large, the cultural and geographical distances separating New York from Hollywood are too vast to allow one to consider either as a single cultural capital in the same way that Paris, London, Rome, or Vienna are, and appearances in Europe to the contrary, there are almost as many factors separating the east and west coasts of the U.S. as there are factors separating, say, New York from Paris or London.

(4) The exhibition histories of films, both commercial and independent, in the U.S. and in Europe, are often quite separate and at variance with one another. Thus the dates most commonly assigned to European films in most U.S. print sources are not when they were made but when they were first released in the States, and the same problem often crops up with the dates assigned in Europe to many American films. To cite one salient example, Monte Hellman’s The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind, two westerns that he shot back to back in the mid-60s, were widely known in European film magazines of that period as examples of the “new American cinema,” but not in many American film magazines because the films never received any theatrical release in the U.S.; their “discovery” by film-conscious filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino came only decades later. Similarly, Peter Emanuel Goldman’s Wheel of Ashes, shot in Europe with Pierre Clementi circa the late 60s, was to the best of my knowledge seen only in Europe.

Based on the limited information that we do have, the principal examples of American “underground” and experimental films that were widely seen in the 60s were mainly shown in contexts that associated them with the burgeoning counterculture of that period: carnivalesque screenings, many of them held at midnight, that were popular precisely because they tended to defy the sexual, sociopolitical, and aesthetic taboos of more conventional filmgoing, and often attracted attention because of police raids and other censorship problems that resulted from this defiance. Screenings of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, and Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour all led on many occasions to arrests of exhibitors who showed them, and if one considers that Warhol’s early films and Gregory Markopoulos’s Twice a Man were first being shown during the same period (1963-64), it becomes clear that explicit homoerotic content had a great deal to do with what made these films popular as well as controversial. And although Warhol continued to direct (and later, produce or at least lend his name to) several homoerotic features during the 60s, this emphasis in popular underground filmmaking largely became supplanted by an emphasis on other factors relating more to hallucinogenic drugs and various visual patterns associated with them.

Both the homoerotic and the hallucinogenic waves in experimental film were directly influential on commercial filmmaking in a number of ways, highlighting the degree to which their wider public impact generally had more to do with their subject matter and with some of the visual styles arising from that subject matter than with their experimental aspects. The Warhol Superstar party attended by the heroes (Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman) in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969) and some of the op art images in Roger Corman’s The Trip are two obvious examples of how quickly certain elements in underground film could find their way to the surface of mainstream productions.

The point at which major experimental films ceased to have this kind of public forum coincided with the advent of the so-called “structural” film as exemplified by such works as Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), Back and Forth (1969), and La région centrale (1971), Ken Jacobs’s Tom Tom the Piper’s Son (1969/1971), and Hollis Frampton’s Nostalgia (1971) — films associated with neither sexuality nor drugs in the minds of most viewers (though an intellectual minority continued to associate Snow’s films with “trips,” in part because of his own interest in drugs). This turning point, moreover, corresponded closely in terms of both period and attitude to the institutionalizing of the American underground film via museums, archives, and academic film studies, which tended to remove experimental films from the social spaces of ordinary or makeshift movie theaters and relegate them to the “safer” confines of various institutional venues (mainly classrooms).

Prior to this change, the experimental film that was probably seen most widely and frequently was Scorpio Rising, and the cultural impact it had, as suggested above, was not closely tied to its experimental aspects, having more to do with its iconography and sexuality and its use of pop records than to its unorthodox cutting and its relatively esoteric symbology. (Indeed, the important roles played in the film by clips of Marlon Brando from The Wild One, a photograph of James Dean, panels from such comic strips as Dick Tracy and Li’l Abner, and a wind-up motorcycle toy all gave the film a much wider address than the mythical references of Anger’s previous and subsequent films.) And the same could be said of the underground films that had the strongest commercial impact a few years later: Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls (1966), Robert Downey’s satirical Chafed Elbows (1967), and, perhaps most significant of all, a traveling program of shorts packaged on the west coast by Mike Getz (an exhibitor who had previously been brought to trial for showing Scorpio Rising) that played in weekend midnight slots at a circuit of theatres owned by Getz’s uncle, Louis Sher. The first such program, which went out in early 1967 under the label “Psychedelic Film Trips #1,”included George Kuchar’s Hold Me While I’m Naked, Storm De Hirsch’s Peyote Queen, and Stan Vanderbeek’s Breathdeath, and according to J. Hoberman — whose chapter on “The Underground” in our co-authored book Midnight Movies is the chief source of this survey — this very successful enterprise peaked in 1969, when it reached twenty-two cities in the U.S., though it continued until the mid-70s.

Though some of these underground movies exerted an effect on 60s Hollywood by helping to loosen up the general public’s sense of what was acceptable in commercial movies — in terms of subject matter, style, and even certain technical standards — their influence was considerably less pronounced than the impact of vanguard European filmmaking during the same years. But to examine more closely the effects of both strains on Hollywood during the 60s and early 70s, it would help to turn to a few individual cases. In some, I’ll be focusing more on the films themselves, and in others I’ll be discussing mainly their critical receptions. As is suggested by my examples, I think it can be argued that, with few exceptions, many of the biggest commercial successes in Hollywood can be attributed more to their popularizing of elements from European films than to their popularizing of elements from the American underground.

Exhibit #A: The Graduate. Released toward the end of 1967, Mike Nichols’s second feature went on to become the top Hollywood money maker of 1968, and its enormous success was — and still is — widely ascribed to the rebellious youth culture of the period. This may seem curious if one considers that Benjamin, the title hero (Dustin Hoffman in his first movie role), wears a coat and tie throughout the picture, unlike his hippie contemporaries, and that his rebellion relates exclusively to personal rather than social or political issues — his determination to marry the daughter (Katharine Ross) of his father’s law partner after having an adulterous affair with her mother, Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft). Indeed, one of the film’s running gags in its latter section is the erroneous impression of a rooming-house landlord in Berkeley that Benjamin is some sort of campus radical when he doesn’t even remotely resemble one.

In order to contextualize this anomaly, it becomes helpful to look at the other top moneymaking pictures of the 60s that had some relationship with “rebellious” youth culture: Splendor in the Grass (1961, set mainly in the late 1920s), Bye Bye Birdie (1962, an adaptation of a stage musical about the impact of a rock-and-roll singer on a small town), A Hard Day’s Night (1964, a film about and starring the Beatles), The Wild Angels (1966, an exploitation feature about a motorcycle gang), Blow-up (1967, Michelangelo Antonioni’s art film about “swinging London,” the only foreign film in this category), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Easy Rider (1969). None of these pictures with the possible exception of the last can be accurately described as an expression or even representation of 60s counterculture apart from a few passing elements; as with the Vietnam war, there was an evident lag time between what was happening in American culture and what the most commercially successful Hollywood pictures were prepared and willing to show. Significantly, when Antonioni himself dealt directly with American counterculture in Zabriskie Point (1970), the film was a resounding flop with audiences and critics alike, and the same could be said of Otto Preminger’s Skidoo the previous year; perhaps only Woodstock (1970) succeeded both in dealing directly with the counterculture and in reaching a wide mainstream audience.

In the case of The Graduate, coming during the middle of this period, the sense of “newness” undoubtedly came less from the film’s subject matter than from its offscreen songs by Simon & Garfunkel — most of them already recorded and released before the film was made — and, above all, from the eclectic, free-wheeling, and attention-grabbing visual style. (Its comic verbal style, by contrast, could be traced in many ways back to Mike Nichols’s own satiric routines with Elaine May, which began in the mid-50s.) And much of that style had clear antecedents in some of the better-known art films of the early 60s — work by such filmmakers as Truffaut, Godard, Antonioni, Fellini, and even, to a more debatable extent, Cassavetes.

The film’s first extended sequence, for instance, is a party given for Benjamin by his well-to-do parents in Los Angeles, attended exclusively by the parents’ friends, and this sequence is filmed almost exclusively in claustrophobic close-ups and hand-held camera movements. The style has a great deal in common with the style of party sequences in Cassavetes’s Shadows (1959) as well as in his subsequent Hollywood feature Too Late Blues (1962) — the release of his better-known Faces was not to come until 1968 — although Andrew Sarris, in his contemporary review of The Graduate, noted that these “bobbing, tracking, lurching heads in nightmarishly mobile close-ups looks like an ‘homage’ to Fellini’s 8½,” which indeed could be a likelier source. Either way, it is a sequence that looks nothing like standard Hollywood filmmaking of the 60s and a great deal like what was then being identified with certain alternative filmmaking practices. (Pointedly, in his same review of The Graduate, Sarris plausibly noted that “A rain-drenched Anne Bancroft splattered against a starkly white wall evokes images in [Antonioni’s] La notte,” and he also cited possible derivations in the film from Agnès Varda’s Le Bonheur and the “landscape work” of American independent John Korty — both reference points of that period that are less likely to be cited or remembered today.)

An even more striking example of this tendency comes at the end of the protracted comic seduction of Benjamin by Mrs. Robinson, his future girlfriend’s mother, who has already ordered him to drive her home from the aforementioned party and has subsequently issued a series of further commands to him when they are alone in her house — to have a drink, to accompany her upstairs, and so on — as she proceeds to remove part of her clothing. This climaxes in a brief scene in which Benjamin, alone in Mrs. Robinson’s daughter’s room, sees reflected in a framed portrait of the daughter the nude figure of Mrs. Robinson (the only name he or the dialogue ever assigns her) entering the room and closing the door behind her. When Benjamin spins around to face her, this single gesture is broken up by the editing into four separate dovetailing shots, each filmed from a different angle, all but the last of which is so brief that the effect is mainly subliminal. (The successive lengths of the four shots are fifteen frames, thirteen frames, one single frame, and then, as Benjamin says “Oh, God!”, seventy frames.) Insofar as the early features of Godard and Truffaut can be said to have visual tropes, this is clearly one of them, though the use of it here is more pointedly and exclusively tied to the viewer’s identification with the subjectivity of a single character than it would have been in the French originals.

This is followed by other shots of Benjamin’s frantic responses to Mrs. Robinson, punctuated by other near-subliminal shots of her nude body — ten frames of her midriff, four frames of one of her breasts, and five frames of her navel — which effectively suggest the sources of his panic without spelling them out. In this case, it is more difficult to point to precise New Wave counterparts and more likely that the pressures of studio censorship led to some of the subliminal abridgements of shots. (The Graduate, one should note, came out after the far-ranging revision of the Production Code in 1966 and prior to the launching of the rating system in 1968 — an in-between period in more ways than one.) Still, the titillating effect of these brief inserts and their stylistic eclecticism both point to the recent inroads made by New Wave films on Hollywood thinking and practices. And the same could be said for many of the other stylistic flourishes of The Graduate, ranging from sound overlaps (such as the beginning of a subsequent scene’s dialogue over the end of the previous sequence) to fancy camera setups (e.g., Mrs. Robinson appearing at a hotel bar rendezvous with Benjamin as a reflection on a glass table) to extended uses of first-person camera (such as the sequence featuring Benjamin inside a deep-sea diving suit, nearly all of it seen from his vantage point).

The most significant differences between the uses of such techniques in New Wave pictures and their uses in Hollywood usually have a great deal to do with the mechanics of storytelling and the identification of the viewer. If the stylistic play of Breathless and Shoot the Piano Player generally had the effect of making the viewer identify with the filmmakers, the stylistic play of The Graduate and many comparable Hollywood movies was more generally motivated by a desire to make the viewer identify with the screen characters, and even if a greater awareness of the director’s role ensued from this process, this was mainly a surplus factor rather than the central one. (By the same token, if the editing of Breathless or Shoot the Piano Player brought the viewer “closer” to the characters in those films, this was also largely a surplus factor.) In The Manchurian Candidate, on the other hand, intermittent audience identification with Laurence Harvey’s assassin and other brainwashed American soldiers in the plot might be said to bring the viewer somewhat closer to an awareness of his or her position as passive, manipulated spectator — an experience roughly comparable to the state of metaphysical free fall afforded by identifying with Delphine Seyrig’s character in Last Year at Marienbad.

Exhibit #B: Bonnie and Clyde. During the same year that The Graduate was released, one could cite a good many other Hollywood features that showed the direct influence of the French New Wave. Even Howard Hawks’s relatively “classic” and conventional El Dorado included a verbal reference to Shoot the Piano Player, which was interpreted by some contemporary critics as Hawks’s acknowledgement of the critical appreciation for his work shown by several New Wave directors (and Sarris, for one, went even further and argued that the citation of Poe in El Dorado also alluded to French criticism). But a more direct and consequential lineage could be traced through such Hollywood pictures as John Boorman’s Point Blank and Stanley Donen’s Two For the Road (two very different pictures that featured Resnais-like editing and a fractured treatment of chronology), Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re a Big Boy Now (which might be regarded as an alternative version of The Graduate that failed to enjoy the same success), and, most influentially of all, Bonnie and Clyde, a script and project that was actually offered to both Godard and Truffaut at separate stages before Arthur Penn took it over.

In terms of its impact, Bonnie and Clyde — though it wasn’t commercially successful enough at first to become one of the top twenty money makers of 1967, and only subsequently was tabulated as the fifteenth top money maker of the 60s (in contrast to The Graduate, which came in second) — probably had a stronger influence on subsequent Hollywood pictures than any of the titles cited above, including The Graduate. The pattern of relatively “unsuccessful” pictures exerting more lasting influence than certified hits is not, of course, restricted to Hollywood; Shoot the Piano Player and Band of Outsiders, the two French films that probably had the strongest influence on Bonnie and Clyde, weren’t commercial successes in either France or the U.S. And it was probably Bonnie and Clyde, out of all the Hollywood pictures released in 1967, that most decisively converted certain attitudes and stylistic devices of the French New Wave into a lasting part of the American mainstream. Along with the early Sergio Leone westerns that preceded it and The Wild Bunch, which appeared two years later, this tragicomic period thriller about the 30s exploits of an outlaw couple was the film that made extravagant bloodletting aesthetically acceptable in the commercial cinema at large.

Interestingly enough, for Pauline Kael, who was in some ways Bonnie and Clyde’s biggest and most significant American champion, the French sources were not altogether a good thing, at least in the way that Penn applied them. One paragraph in her famous, extended defence of the film deserves quoting in full: “If this way of holding more than one attitude toward life is already familiar to us — if we recognize the make-believe robbers whose toy guns produce real blood, and the Keystone cops who shoot them dead, from Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player and Godard’s gangster pictures, Breathless and Band of Outsiders — it’s because the young French directors discovered the poetry of crime in American life (from our movies) and showed the Americans how to put it on the screen in a new, ‘existential’ way. Melodramas and gangster movies and comedies were always more our speed than ‘prestigious,’ ‘distinguished’ pictures; the French directors who grew up on American pictures found poetry in our fast action, laconic speech, plain gestures. And because they understood that you don’t express your love of life by denying the comedy or the horror of it, they brought out the poetry in our tawdry subjects. Now Arthur Penn, working with a script [by Robert Benton and David Newman] heavily influenced — one might almost say inspired — by Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player, unfortunately imitates Truffaut’s artistry instead of going back to its tough American sources. The French may tenderize their American material, but we shouldn’t. That turns into another way of making ‘prestigious,’ ‘distinguished’ pictures.”

Ideologically speaking, one might argue that the most pivotal words in this polemic are all first-person plural pronouns: “us” and “our” in the first sentence, “our” (used twice) in the second, and “we” in the fourth. They all imply a fundamental cleavage between French and American sensibilities, French and American audiences, and even what might be called French and American property in terms of both life and history, including film history. Thus both French cinephiles who might have regarded certain American crime pictures as “our movies” — not necessarily to the exclusion of Americans, but in concert with them — and Americans who might have felt the same way about certain New Wave pictures become automatically and irrevocably excluded from Kael’s line of reasoning; the very notion of a shared tradition is deemed inadmissible by definition. In more ways than one, the xenophobic underpinnings of Cold War rhetoric are faintly echoed in this kind of critical discourse, and these strains were to become more rather than less pronounced — and not only in Kael’s prose — in the years to come. Though one has to acknowledge that Kael was offering here a sharp social critique of the American snobbery that during this period was often valuing continental filmmaking over its American sources — a form of snobbery that has subsequently all but vanished from the American mainstream — the fact remains that this passage reeks with intimations of property rights. Nor should it be overlooked that Kael herself is far from being entirely exempt from the cultural snobbery she assigns to other Americans; a phrase such as “the poetry in our tawdry subjects” indirectly implies that French crime — and the whole strain of French filmmaking devoted to it, which she strategically ignores — is not so tawdry.

Significantly, Kael virtually began her defence of Bonnie and Clyde by calling it “the most excitingly American American movie since The Manchurian Candidate.” This meant factoring out any recognition of the fact that, quite apart from the possibility that The Manchurian Candidate may have been influenced by the French New Wave, it could — and perhaps should — also be seen as an American movie that paralleled much of what was going on in the more adventurous strains of French filmmaking at the time by mixing various genres and traditions, to the consternation and confusion of many filmgoers on both sides of the Atlantic. The degree to which Americans and Europeans shared many traditions and assumptions during the early 60s shouldn’t be overlooked, however much this complicates the usual scenarios of influence and appropriation. This is not to argue that the same pictures were always understood in the same ways wherever they showed, only that to some extent Americans and Europeans were swimming in the same waters. If some Americans (as well as some Europeans) tended to miss many of the comic and parodic aspects of Marienbad, released the same year (1962), it seems likely that some European (as well as some American) viewers missed many of the equivalent elements in John Frankenheimer and George Axelrod’s film.

It’s also worth stressing that neither Marienbad nor The Manchurian Candidate were films that could be assimilated to the same degree that Breathless, Shoot the Piano Player, or Band of Outsiders were when they first appeared. As Axelrod noted in 1968 of The Manchurian Candidate, “it went from failure to classic without ever passing through success,” and it probably wasn’t until the film’s re-release in 1988 that most critics were finally able to come to terms with it. By then, of course, the critical climate for what was acceptable in Hollywood cinema was considerably different.

But in the case of Marienbad, which enjoyed some success and notorièty as a foreign arthouse film in 1962, the film can’t be said to have “survived” at all, critically or otherwise: today the film is available in the U.S. in 16-millimeter and on video only in a “scanned” version that eliminates about a third of the image, and in recent years it has never been re-released or revived in theatres in any form at all; very few filmgoers under the age of twenty-five have heard of it, and few of Resnais’s recent features have been released in the U.S. [2003 postscript: I can no longer remember the precise date when I wrote this—ten years ago would be a safe approximate guess—but it’s delightful to report that it’s now an anachronism; a letterboxed DVD of Marienbad is readily available in the U.S.] Properly speaking, the license extended to experimentation in American commercial moviegoing in the 80s and 90s goes no further than Hollywood; it can embrace a Natural Born Killers — which might be regarded as the bastard great-grandson of Bonnie and Clyde, if not a movie with any comprehensible relationship to the American avant-garde — but not any foreign counterparts.

Exhibit #C: Easy Rider (1969). For all its own — and more sophisticated — derivations from the American avant-garde, Dennis Hopper’s first feature surely owed most of its commercial success to elements that had relatively little to do with this relationship. Perhaps the most important of these elements was Jack

Nicholson’s performance as an alcoholic, small-town southern lawyer who briefly joins the two heroes, Billy (Hopper) and Captain America (Peter Fonda, the film’s producer), on their cross-country motorcycle trek to New Orleans — a fresh and multi-faceted character that benefited from Terry Southern’s dialogue and was undoubtedly the major factor in turning Nicholson into a star. Another such element may have been the film’s striking and unconventional handling of violent deaths, which critic Manny Farber wrote about perceptively at the time.

In his Allegories of Cinema, David E. James interestingly argues how Hopper’s appropriation of “alternative” film practices in Easy Rider “lit the way for a new Hollywood” at the same time — and perhaps for the same reason — that it deradicalized those practices. Some of his specific examples of appropriation, however, seem rather contestable: “[Several] visual motifs — flash cutting between shots, an extended interlude of subjective psychedelic vision, and an overall looseness in scene construction, for instance… [all] derive from previous alternative film: the basic motif of the journey from west to east and the overall ethical structure derive from Bruce Baillie’s Quixote; flash frames which signify subjectivity or anticipation, or which diffuse transitions between scenes, derive from Stan Brakhage; the hand-held camera and the use of anamorphic lenses in the trip sequence are the staple motifs of countless underground films; the caressing attention to the technological sensuousness of the motorcycles derives from Kenneth Anger’s Kustom Kar Kommandos, as the use of rock music structurally and as ironic counterpoint derives from his Scorpio Rising; the occasional ‘real life’ confrontations, such as that with the young man in the street in New Orleans, are borrowed from cinéma verité; and the documentation of the counterculture and its more or less scandalous rituals — drugs, nudity, communal habitation — is the defining function of underground film as a whole, originating in the various documentations of beatnik life in the late fifties. But since Hopper fails to assimilate the film practices of various dissenting and countercultural groups into a coherent style,” James goes on to say, “the film remains a pastiche, an essentially orthodox industrial product, decorated with unamalgamated infractions.”

But these appropriations, which James goes so far as to label as plagiarisms, are in some cases arguably much less specific and localized than he implies. The “caressing attention” to “technological sensuousness” — i.e, the worshipful pans across the motorcycles of Billy and Captain America — seem to have at least as much to do with the motorcycles in Scorpio Rising as they do with the custom-made hot rods in Kustom Kar Kommandos, and Hopper’s frequent use of pop records, which includes more than just rock music, has virtually none of the wit or irony of Anger’s uses of “Fools Rush In,” “Blue Velvet,” “Look Like an Angel,” and “Point of No Return” (among other songs) in Scorpio Rising. It’s also questionable whether the so-called “flash frames” in Easy Rider (virtually all of which last longer than single frames) are directly attributable to the more radical and relatively non-narrative editing strategies of Brakhage, or whether a journey from the west coast to the east coast necessarily entails any “plagiarism” of Baillie’s Quixote. In short, unlike the so-called “hommages” to well-known film sequences that pepper the postmodernist Hollywood pictures of such 70s filmmakers as Woody Allen, Peter Bogdanovich, Brian De Palma, and Martin Scorsese, Hopper’s uses of elements from “alternative” American filmmaking practices are generally not so much plagiarisms or appropriations as popularized applications, and the same could be said for most other crossovers from underground to mainstream.

Exhibits #D, #E and #F: The Last Movie, Glen and Randa, and Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). The second feature of Dennis Hopper, The Last Movie, marks both the beginning and the end of another, albeit related kind of experimentation — the radical American “underground” film that aimed for mainstream or at least art film status and was fed by the American (as well as European) avant-garde, while Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop and Jim McBride’s Glen and Randa represent related efforts that exist in the same, rather specialized no-man’s-land. One could, of course, cite a good many other productions that exhibited a few of the same superficial characteristics: Hopper’s own previous Easy Rider (1969) and James William Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue (1973), both of which showed the marked influence of Scorpio Rising; Roger Corman’s The Trip (1967), which was partially inspired by the “psychedelic” imagery of other American experimental films, by Anger and others. Even some of Paul Mazursky’s wholesale borrowings and appropriations of Fellini and Truffaut and his evocations of hippie culture in his 70s pictures — stretching from Alex in Wonderland (1970), which included both Frederico Fellini and Jeanne Moreau in its cast (along with the latter’s song from Jules and Jim) to the no less feeble Willie and Phil (1980), an American “remake” of Jules and Jim — retrospectively belong to the same overall zeitgeist, in spite of their more middle -class inflections.

But The Last Movie, as its very title suggests, is substantially more radical in form as well as content than any of these, and David E. James rightly shows how Hopper’s multifaceted critique and analysis of Hollywood imperialism in a third world context (a western being shot in a remote Peruvian village) logically led to the film’s commercial failure: “In the context of an exploitative cinema of pleasure, its own constitution as analysis amounted to its constitution as negation that could be legitimized only by the absoluteness of its rejection by the degraded public.” Featuring such Hollywood icons as Hopper himself and Samuel Fuller, and benefiting from a substantial budget, the film’s bold oscillation between various uncompleted plots and its numerous self-referential devices — such as the incorporation of unedited rushes, successive takes of the same shots, and even animated, handwritten titles announcing “Scene Missing” — staged a kind of ultimate shotgun marriage between Hollywood and the avant-garde that could only confound and alienate the expectations of both constituencies. Characteristically, the most common form of critical rejection that greeted the film was seeing it as a failed commercial effort rather than as a calculated provocation with a logic and form of its own. (Pauline Kael: “Hopper may have the makings of a movie [perhaps more than one], but he blew it in the editing room. If he was deliberate in not involving the audience, the audience that is not involved doesn’t care whether he was deliberate or not. That there’s method in the madness doesn’t help. The editing supplies so little in the way of pace or rhythm that this movie performs the astounding feat of dying on the screen in the first few minutes, before the credits come on.”) By the same token, the Hollywood budget accorded to Hopper seemed to guarantee a disinclination on the part of critics associated with experimental films and art films to deal with the film seriously on any level at all, and in the final analysis, the film was effectively disenfranchised by the mainstream, the underground, and the art film intelligentsia alike, with equal vehemence.

Virtually the same thing would happen with both Glen and Randa and Two-Lane Blacktop, both released during the same year, and both offering complex and considered (albeit implicit rather than explicit) critiques of Hollywood in form as well as content. Viewed with some hindsight, the fate of all three features was more or less determined by the absence of any media machinery that could accommodate a film that wasn’t protected or claimed by any predefined social constituency. Concise packaging labels were in effect necessary before a film could qualify for membership in any of the existing canons: if it wasn’t a Hollywood film or an art film or an experimental film in any obvious way, and if it didn’t adequately conform to a clear genre classification within or outside any of these categories, in certain respects it didn’t — and couldn’t — exist critically at all, because influential critics at the time usually weren’t disposed to create new categories in order to account for them. Thus it wasn’t enough to classify Glen and Randa as a science fiction film (although its story unfolded in the future, in a clearly post-apocalyptic and post-nuclear era) or Two-Lane Blacktop as a car-racing movie (although most of its own story consisted of a race between two cars) because, in each case, and wholly in keeping with the implicit critique of Hollywood genre propounded in each picture, the genre expectations set up by each of these classifications were deliberately thwarted.

Although he didn’t write the original story in either case, the contributions of avant-garde novelist Rudolph Wurlitzer to the scripts of both these films seems emblematic of a certain literary sensibility, both existentialist and absurdist, that helped to confound these genre expectations. At this point in his career, Wurlitzer had published two Beckett-influenced modernist novels with certain countercultural trappings, Nog (1969) and Flats (1970), both of which had attained some literary prestige; perhaps for this reason, the script of Two-Lane Blacktop was published in its entirety in a single issue of Esquire prior to the film’s release. But the literary audience that supported Wurlitzer seemed to have negligible crossover with the film audience, and the persistence of Wurlitzer’s themes in these two pictures — much more pronounced in the case of Two-Lane Blacktop — had scant effect on their critical or popular receptions. This points to a striking contrast with the more symbiotic and interactive literary and film worlds of France, where the contributions of Marguerite Duras and Alain Robbe-Grillet to the first two features of Alain Resnais played a more noticeable role in enhancing the reputations of these films. (Similarly, the art world strategies employed by Hopper in The Last Movie couldn’t be recognized as such within the critical mainstream of either art criticism or film criticism — with the result that they were often written off as the drug-induced ravings of a maverick who had finally lost all perspective on his work.)

For all their aforementioned parallels, including Wurlitzer’s participation, Glen and Randa and Two-Lane Blacktop were quite different in other respects. The former was the first relatively large-budget feature of a director, Jim McBride, who had previously worked only in the New York underground, in David Holzman’s Diary (1967) and My Girlfriend’s Wedding (1969) — two films that were highly influenced by the French New Wave, especially in their Godardian ambiguities regarding documentary and fiction. (The first was a pseudo-documentary fiction, the second a genuine documentary that played with various attributes of fiction.) Based on a story by Lorenzo Mans, an actor in David Holzman’s Diary, Glen and Randa was a playful fantasy and a cultural satire couched in the form of a science-fiction parable and shot in a pseudo-ethnographic style, charting the progress on foot of an illiterate hippie couple across the American northwest wilderness, after a nuclear holocaust, as the hero searches for the city of Metropolis, which he has “learned” about from a Wonder Woman comic book. In terms of genre expectations, the only way an audience of science-fiction fans could have been satisfied would have been if Glen and Randa had actually reached this mythical city, a possibility that both the film’s pseudo-documentary style and its satirical vantage point precluded. (To underline this refusal to play by the Hollywood rules, the film’s original, pre-release title was Glen and Randa Go to the City, despite the fact that the film ends quixotically with the couple and their newborn child sailing off in the Pacific Ocean, still in search of Metropolis.)

Two-Lane Blacktop, on the other hand, came from a director, Monte Hellman, who already had some background in low-budget, Hollywood genre filmmaking — The Beast from Haunted Cave (1959), Back Door to Hell and Flight to Fury (1965), and The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind (1966) — even though the latter two westerns, undoubtedly because of their own confounding of genre expectations, had never opened in the U.S. And the putative plot of Two-Lane Blacktop, involving a cross-country race between two cars, seemed to promise action and adventure to an audience that might well have tolerated picaresque digressions in relation to this simple framework, particularly after the huge success of a film like Easy Rider. But at least two strategies worked fairly systematically to undermine these expectations: (1) At least two of the leading roles were played by non-professionals, James Taylor and Laurie Bird, while the leading actor with the most visible skills, Warren Oates, played a character so deliberately mutable and unfixable — like the hero and narrator of Wurlitzer’s Nog — that he was identified in the credits only by the name of his car, GTO. Taylor and Bird were identified in the same credits only as “the driver” and “the girl,” and the film’s overall treatment of personal identity was sufficiently abstract and “empty” to confound most conventional notions of psychological motivation and continuity. (2) The “picaresque digressions” so steadily undermine the premise of the race itself in diverse ways that the narrative itself progressively begins to dissolve and disperse, rather like the character of Tyrone Slothrop in the final sections of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow — finally achieving something close to total incoherence after “the girl” arbitrarily exits the film — and the race’s conclusion is never reached; during a final digression, the film itself appears to burn up in the projector instead.

In short, the refusals of narrative and genre closure in all three of these features, despite the setting up of narrative and genre expectations in each case, wound up excluding these films from any sort of mainstream acceptance, while the setting up of those expectations wound up excluding them from any consideration as art films or experimental films. (Only within a few limited European circles were these films ever accepted as art films.) Within the canons of American film culture itself, it could even be argued that these films have virtually been written out of film history a quarter of a century later, simply because most mainstream and academic critics have still found no place or space for them in their surveys. To survive in such arenas, affiliation with “commercial” or “alternative” branches of cinema usually becomes necessary; to exist between these branches means in most cases not to exist at all.

Exhibit #G: Taxi Driver (1976). A film that clearly shows the influence of both American experimental filmmaking and vanguard European narrative filmmaking of the 60s, Taxi Driver can be said to have at least three central auteurs — director Martin Scorsese, screenwriter Paul Schrader, and lead actor Robert De Niro — the first two of whom were deeply marked by both kinds of filmmaking. In what is still undoubtedly the best critical study of the film, “The Power & the Gory” (Film Comment, May-June 1976), Patricia Patterson and Manny Farber do a good job of showing how such influences and others coexist with blatantly commercial Hollywood elements:

“Taxi Driver is always asserting the power of playing both sides of the box-office dollar: obeisance to the box-office provens, such as concluding on a ten-minute massacre, a sex motive, good-guys vs. bad-guys violence, and casting the obviously charismatic De Niro to play a psychotic, racist nobody…. On the other coin side, it’s ravishing the auteur box of Sixties best scenes, from Hitchcock’s reverse track down a staircase from the Frenzy brutality, though Godard’s handwriting gig flashed across the entire screen, to several Mike Snow inventions (the slow Wavelength zoom into a close look at the graphics pinned on a beaten plaster wall, and the reprise of double and triple exposures that ends Back and Forth …. Taxi Driver is actually a Tale of Two Cities: the old Hollywood and the new Paris of Bresson-Rivette-Godard.”

Early in the same essay, Patterson and Farber note “the jamming of styles: Fritz Lang expressionism, Bresson’s distanced realism, and [Roger] Corman’s low-budget horrifics,” before going on to note specific echoes of scenes from other sources: “De Niro’s cab almost collides with the two child-whores — just as Janet Leigh’s fearful Psycho thief nearly overruns the man from whom she’s stolen a bundle …. When De Niro stares at his Alka Seltzer glass, there is a tiny sneak zoom into the bubbling water, which adds one more shot to Godard’s rapidly-spoken philosophizing [2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle] in which the camera frames the coffee cup from above.” And Kael has separately described a scene where the camera moves away from the hero on a pay phone to an empty hallway as “an Antonioni pirouette”.

These are of course only a few sources of the film among many. Schrader has noted in interviews how some lines in De Niro’s narration are taken directly from Bresson’s Le Journal d’un curé de campagne and that the film’s very title was suggested by Pickpocket. He has also said, “Before I sat down to write Taxi Driver, I reread Sartre’s Nausea, because I saw the script as an attempt to take the European existential hero, that is, the man from The Stranger, Notes from the Underground, Pickpocket, Le feu follet, and A Man Escaped, and put him in an American context. In so doing, you find that he becomes more ignorant, ignorant of the nature of his problem.” He has also described in some detail how certain aspects of the plot were suggested by Ford’s The Searchers.

The apparent incompatibility of these various influences — Bresson, Ford, Antonioni, Godard, Hitchcock, Snow, Lang, Sartre, Camus, Dostoevsky, Malle — tend to be overcome by an overall process that seems analagous to the process noted earlier in assimilating the New Wave influences into strict identification with the central character in The Graduate. The relatively socialized contexts of most of these influences become privatized into the alienation of a single individual (though in the case of Snow, it might be argued that the source was already relatively privatized and antisocial to begin with; as noted earlier, it was the “structural” films of Snow, Jacobs, Frampton, and others that largely removed experimental film from a carnivalesque social setting and into classrooms.) Perhaps the most pertinent difference in this case is that the character being identified with in Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle, is not a mildly rebellious middle-class youth, as in The Graduate, but a working-class Vietnam veteran who is virtually a psychopath and winds up committing mass murder.

The degree to which Scorsese, Schrader, and De Niro identify with Bickle is moreover even more consequential than the degree to which the filmmakers of The Graduate can be said to identify with Benjamin. And significantly, if one turns to Schrader’s own accounts of his artistic intentions in interviews, the degree of moral conflict and confusion — no doubt stemming in part from Schrader’s strict Calvinist upbringing — seems to border at times on the pathological, at least in relation to the film’s actual impact on most audiences: “The controversial nature of the film will stem, I think, from the fact that Travis cannot be tolerated. The film tries to make a hard distinction for many people to perceive: the difference between understanding someone and tolerating him. He is to be understood, but not tolerated. I believe in capital punishment: he should be killed.” (“Screenwriter: Taxi Driver’s Paul Schrader interviewed by Richard Thompson,” Film Comment, March-April 1976.)

“At the time I wrote [the script] I was very enamoured of guns, I was very suicidal, I was drinking heavily, I was obsessed with pornography in the way a lonely person is, and all those elements are upfront in the script. Obviously some aspects are heightened — the racism of the character, the sexism …. In fact, in the draft of the script that I sold, at the end all the people he kills are black. [Scorsese and the producers] and everyone said, no, we just can’t do this, it’s an incitement to riot; but it was true to the character.” (Schrader on Schrader, edited by Kevin Jackson, London/Boston: Faber and Faber, 1990).

Indeed, Patterson and Farber persuasively argue that the final film is itself racist, sexist, and worshipful of guns while Bickle himself is romanticized and largely excused: “The fact is that, unlike the unrelentingly presented worm in Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, this handsome hackie is set up as lean and independent, an appealing innocent. The extent of his sexism and racism is hedged. While Travis stares at a night world of black pimps and whores, all the racial slurs come from fellow whites.”

In short, thanks to what might be termed the Hollywoodizing of Taxi Driver’s experimental and European elements — a process involving such elements as Bernard Herrmann’s effectively romantic/bombastic score, the charisma of De Niro, and the slickness of Michael Chapman’s cinematography, as well as the displacements noted above by Patterson and Farber — the audience is invited to identify with a violently Calvinist, racist, sexist, and apocalyptic wish-fulfilment fantasy, complete with an extended bloodbath, that is given all the allure of expressionist art and involves very few moral consequences for most members of the audience. (At the film’s end, Bickle is declared a hero and even wins the admiration of the heroine, Cybil Shepherd, who previously spurned him — a Hollywood conclusion in more ways than one.) Because the whole thing is taking place inside one glamorous individual’s head, the social ramifications are effectively rationalized to the point of non-existence. In more ways than one, this is the overall direction that Hollywood at its most triumphant will follow for the next two decades in processing and refining its various transgressive legacies; even a film like Schindler’s List will follow essentially the same tactics, arguably with many of the same results.

————————————————————————————–

Major references:

————————————————————————————–

Farber, Manny and Patricia Patterson, “The Power and the Gory,” in Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies, expanded edition, New York: Da Capo, 1998.

Film Culture nos. 26 and 27, 1962.

Hoberman, J. and Jonathan Rosenbaum, “The Underground,” in Midnight Movies, expanded edition, New York: Da Capo, 1991.

James, David E., “Considering the Alternatives” (Chapter 1), in Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties, Princeton,NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Kael, Pauline, “Bonnie and Clyde,” in For Keeps, New York: Dutton, 1994.

New York Film Bulletin nos. 43 and 44, 1962.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan, “The Manchurian Candidate,” in Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism, Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995.

Sarris, Andrew, “The Graduate,” in Confessions of a Cultist: On the Cinema, 1955/1969, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971.