JACQUES TOURNEUR, edited by Fernando Ganzo, Locarno Festival/Cinémathèque Suisse/Capricci,224 pages, 23 Euros.

Published to accompany the Jacques Tourneur retrospective at the Locarno Festival last August, this collection has been issued in separate English and French editions; Capricci has kindly sent me a review copy of the former, and although I’ve only just started to dig into its contents, I’m looking forward to many pleasurable and profitable times with the rest. Apart from translating a few important texts from the past — extended interviews with Tourneur in Cahiers du Cinéma and Présence du Cinéma (both in 1966), an essay by Petr Král from Caméra/Stylo in 1986 — this book mainly consists of new essays, most of them translated from over a dozen French writers (including Pierre Rissient, Patrice Rollet, and Jean-François Rauger) and two Americans (Chris Fujiwara and Haden Guest). There are also many illustrations in this slightly oversized volume, My only complaint is with the layout that prints about two dozen pages of the text on a shade of dark grey that makes them extremely (and needlessly) difficult to read. If Marc Lafon, the book’s design person, was trying to approximate some notion of Tourneur as the poet of shadows, I’m afraid this effort was misguided, because all that comes out of this exercise is murkiness, not poetry. Read more

From Sight and Sound, July 2017. — J.R.

WILLIAM FAULKNER AT TWENTIETH CENTURY-FOX

The Annotated Screenplays

Edited by Sarah Gleeson-White, Oxford University Press, 949 pp., ISBN 9780190274184

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

We know that Faulkner was no cinephile, but it’s less known that he referenced Eisenstein in The Wild Palms and cited Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons as two of his favourite films (along with High Noon) in a 1958 interview. One also can’t read the present-tense opening of Light in August without noting its cinematic immediacy, which suggests that consciously or not, Faulkner learned a lot from the movies.

Yet when it comes to his screenwriting, it’s closer to alienated, assembly -line labour than any significant form of self-expression. Editor Sarah Gleeson-White, a Sydney-based literary scholar, is well aware of this problem, beginning her Introduction with contradictory statements from Faulkner about how seriously he took this work (both of which, unsurprisingly, sound perfectly sincere) while noting that he wrote around fifty Hollywood screenplays between 1932 and 1954. That Faulkner was fully capable of working simultaneously on both his novel Absalom, Absalom and Hawks’ The Road to Glory is also duly noted. But Gleeson-White’s ambivalence about what actually constitutes screen authorship is reflected in the fact that several photographs in her commentaries are devoted to Faulkner’s Fox collaborators and none at all to Faulkner himself. Read more

From the Boston Phoenix (September 15, 1989). — J.R.

This enjoyable documentary about American comic books takes up a subject so fruitful and entertaining, it’s surprising no one has ever made such a film before. Canadian filmmaker Ron Mann — whose previous cultural investigations include feature-length documentaries about avant-garde jazz (Imagine the Sound) and North American poets who sing and chant their works (Poetry in Motion), and who is currently preparing a feature about the Twist — dives into his chosen turf with the zeal and affection of a voracious fan.

Starting out with the inception of comic books, in 1933, Mann gives us breezy surveys of the superheroes (such as Superman, Batman, and the Fantastic Four), EC Comics (which produced the best horror and sci-fi comics in the 50s and spawned the original version of Mad), the underground artists (such as Robert Crumb and Spain Rodrigues) who emerged in the 60s, and more recent figures such as Art Spiegelman, Sue Coe, and Lynda Barry, as well as the deliberations and operations of Raw, a contemporary publicatiin with a somewhat more self-conscious notion of the comic book as art.

Some of Mann’s funniest material is archival footage of anti-comic-book propaganda from the 50s, when Dr.

Read more

Written for the Chicago Reader (October 12, 2017). — J.R.

Golden Years

Nos Années Folles, the French title of this exquisitely upholstered and mysteriously provocative period drama, means “Our Crazy Years.” But as writer-director André Téchiné has suggested in such masterpieces as Wild Reeds and Thieves, being “crazy” simply means being human, alive, and horny. The protagonist (Pierre Deladonchamps), a passionately heterosexual soldier, disguises himself as a streetwalker to escape combat in World War I, then continues to wear drag in peacetime, yet his behavior seems no less rational (to him or to us) than that of little boys playing at war, or his adulterous wife (Céline Sallette) playing at marriage. For better and for worse, the mysteries remain unsolved and Téchiné’s elliptical tragic poetry prevails. —Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

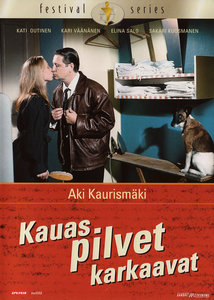

From the Chicago Reader (July 10, 1998). One thing that has recently led me to reconsider my estimation of Aki Kaurismaki is this superb, engaging appreciation of him by Girish Shambu.– J.R

Drifting Clouds

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Aki Kaurismaki

With Kati Outinen, Kari Vaananen, Elina Salo, Sakari Kuosmanen, Markku Peltola, and Matti Onnismaa.

It might be risky to generalize about national character after visiting a country for only a week, but the particular kind of self-deprecating humor in all six features I’ve seen by Aki Kaurismaki was equally apparent during my recent visits to both Helsinki and the Midnight Sun film festival in Sodankyla. Kaurismaki and his older brother Mika, also a filmmaker, are the founders and guiding spirits of this festival, and its artistic director is one of their best friends, so the humor I’m describing is probably a type that flourishes under their eccentric auspices.

Roughly speaking, this attitude derives in part from the belief that Finns are perceived as the Poles of Scandinavia. Their language shares more roots with Hungarian and Estonian than with Swedish, Danish, or Norwegian, and Helsinki, by virtue of being only a few hours from Saint Petersburg, may have more links with Russia than with its Nordic cousins. Read more

Commissioned by and written for the Italian web site 8 1/2, published in September 2017. — J.R.

When asked what I think about current American cinema, my first response is to ask another question: whose American cinema? Because given the splintering of both the audience and all the possible venues for what we now call American cinema, it’s no longer possible to describe it as a single homogeneous entity.

Perhaps it was always wrong to describe it as such, but when I was growing up in the 1950s, there was still an American cinema that appeared to belong to everyone. Today we have only a series of separate niche markets and venues that seem to exist independently of one another. For the sake of both clarity and candor, I should confess that from 1987 through 2007, I was the principal film critic for the principal alternative newspaper in Chicago, the Chicago Reader, which meant that I was professionally obliged to keep up with what was regarded, rightly or wrongly, as “current American cinema”. Since my voluntary retirement from that post, I’ve been a cinephile with no professional obligations, and my preferences in that capacity have been to systematically avoid films featuring superheroes, most horror films and war films, sports films, blockbusters, and most of the other releases mainly targeted for teenage and preteen boys. Read more

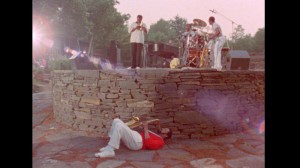

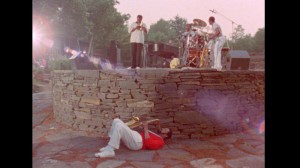

Most of what makes this 1986 Robert Mugge documentary, named after Rollins’ best early album and produced by his late wife Lucille (seen above), so special is Sonny Rollins himself — currently approaching his 87th birthday — as a performer and improviser and his irrepressible stamina and power, combined with his choreographic skill in standing, walking, leaping, and tilting every which way while he plays his tenor sax and pours out his endless inventions. I’ve often thought in the past that jazz vibes players are the most cinematic of performers, because they can only play vibes by dancing, but Rollins has the rare and paradoxical capacity of doing the same thing while looming before us like a veritable mountain. At one point we even see him breaking his heel after leaping from the stage but continuing to play while lying on his back.

The most memorable portions of Saxophone Colossus are two rollicking numbers, “G-Man” and (more abbreviated) “Don’t Stop the Carnival,” performed by Rollins with his quintet at Opus 40, the 6.5-acre environmental sculpture in Saugerties, N.Y. (see above) by the late Harvey Fite (1903-1976), who founded the fine arts program at my alma mater, Bard College. Less memorable to see and hear are portions of a concerto with a symphony orchestra performed at a premiere in Tokyo — not the sort of Third Stream monstrosity one might imagine, but still a composition that unavoidably reins Rollins in, both musically and gymnastically, at the same time that it inflates his cultural profile. Read more

Written for Criterion’s Blu-Ray release of Ozu’s Good Morning and I Was Born, But… in 2017. — J.R.

Structures and Strictures in Suburbia

Jonathan Rosenbaum

From its very opening, Good Morning is deeply and delightfully musical, both in its orchestrations of static visual elements in the first two shots (the juxtaposition of adjacent houses with fences and clotheslines, and all these horizontals with the verticality of electrical towers) and in its varying rhythmic patterns of human movement, which are no less orchestrated, as various figures cross the pathways between houses, between houses and hill, and on top of the hill itself—always, mysteriously, moving from right to left. And what could be more musical than the opening gag, occurring on the same sunny hilltop, of little boys farting for their own amusement, still another form of theme and variations?

All of which prompts me to disagree respectfully with the late Ozu specialist Donald Richie when he maintained, “Good Morning, in some ways Ozu’s most schematic film, certainly one of his least complicated formally, is an example of a film constructed around motifs.” Certainly the motifs are there, and these are vital; the two examined by Richie as sterling examples are the farting and the greeting embodied in the film’s title, and numerous variations are run on both. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 2007). — J.R.

If you were delighted by the euphoric cynicism about corruption in L.A. Confidential and Chicago (I wasn’t), you probably should make a beeline for Joel and Ethan Coen’s brittle farce about corruption in divorce proceedings, in which hotshot lawyer George Clooney and professional divorcee Catherine Zeta-Jones are too busy screwing each other in the courts to show much interest in actual sex. Buffing up a script they’d worked on eight years earlier with Robert Ramsey, Matthew Stone, and John Romano, the Coens do an efficient job of stamping their signature grotesquerie on sumptuous Beverly Hills and Las Vegas settings and ladling on gallows humor and malice, sometimes with the verve of early Robert Zemeckis. Geoffrey Rush, Cedric the Entertainer, Billy Bob Thornton, Edward Herrmann, and Richard Jenkins round out the gallery of cartoon fools. PG-13, 100 min. (JR)

Read more

Written for Il Cinema Ritrovato’s 2019 catalogue. — J.R.

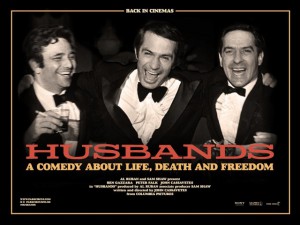

HUSBANDS

Subtitled “A Comedy about Life, Death and Freedom,” John Cassavetes’ most politically incorrect and machocentric movie (1970), made after the huge commercial success of his 1968 Faces and exercising both the creative control and the studio support it suddenly made possible, is arguably the most improvised and workshopped of his features. Inspired in part by the death of Cassavetes’ older brother Nick in 1957 at the age of 30, the film recounts what happens to a trio of 40ish east coast suburbanites (Cassavetes, Peter Falk, and Ben Gazzara) when their best friend dies and they decide to play hooky from their lives and families to recover their camaraderie and identities. But even though their collective flight seemingly has something to do with life, death, and freedom, there isn’t a Huck Finn in the bunch; they’re all Tom Sawyers, too desperate in their frantic fun and games to be as comic as they want to see themselves. Their fear of female assertiveness and their periodic brutality, as well as Cassavetes’ determination to follow the actors’ instincts and movements wherever they go without chalk marks are likely what inspired Elaine May to co-opt Cassavetes, Falk, and Husband’s cinematographer Victor J. Read more

These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the sixth dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

Too Early, Too Late

This 1981 color documentary by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, one of their few works in 16-millimeter, is almost certainly my favorite landscape film. There are no “characters” in this 105-minute feature about places, yet paradoxically it’s the most densely populated work in their oeuvre to date. The first part shows a series of locations in contemporary France, accompanied by Huillet reading part of a letter Friedrich Engels wrote to Karl Kautsky describing the impoverished state of French peasants, and excerpts from the “Notebooks of Grievances” compiled in 1789 by the village mayors of those same locales in response to plans for further taxation. The especially fine second section, roughly twice as long, does the same thing with a more recent Marxist text by Mahmoud Hussein about Egyptian peasants’ resistance to English occupation prior to the “petit-bourgeois” revolution of Neguib in 1952. Both sections suggest that the peasants revolted too soon and succeeded too late. One of the film’s formal inspirations is Beethoven’s late quartets, and its slow rhythm is central to the experience it yields; what’s remarkable about Straub and Huillet’s beautiful long takes is how their rigorous attention to both sound and image seems to open up an entire universe, whether in front of a large urban factory or out on a country road. Read more

The following is a chapter from my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983), a volume commissioned as the first in a projected annual series that would survey recent independent and experimental filmmaking. (A second volume, Film: The Front Line 1984, by David Ehrenstein, appeared the following year, but lamentably the series never continued after that, for a variety of reasons, even though both volumes remain in print.) I have followed the format used in both books.

It’s worth adding that De Landa abandoned filmmaking not long after this article appeared –- after planning, as I recall (but not shooting), a film starring his penis, to be entitled My Dick — and went on to pursue a distinguished academic career as a professor of art, architecture, and philosophy in New York, Pennsylvania, and Switzerland, with at least four books to his credit: War in the Age of Intelligent Machines (1991), A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (1997), Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (2002), and A New Philosophy of Society (2006). For this reason, I couldn’t originally illustrate this piece with any images from his films, as I did in Film: The Front Line 1983, until some frame enlargements were recently made from Incontinence,a month after this article was originally posted, by Georg Wasner of the Austrian Film Museum, to use in a catalogue for a retrospective that I programmed (see below).Most Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 2000). — J. R.

A chilling, mesmerizing, intense account of ethnic cleansing (in spirit if not in letter) from Hungarian master Bela Tarr (2000, 145 min.), set in virtually the same overcast, rural black-and-white world as his Damnation and Satantango (both also cowritten by Laszlo Krasznahorkai). As in Satantango, Krasznahorkai worked with Tarr in adapting his own novel — in this case the first to be translated into English, The Melancholy of Resistance, elaborately restructured here in terms of narrative sequence and viewpoint so that it’s mainly limited to the experience of a simpleminded messenger and artist figure. A decrepit circus (actually a huge truck) in an impoverished town displays the stuffed body of the largest whale in the world while spreading rumors about but failing to deliver a foreign prince. Eventually the unemployed male locals head for the local hospital like a lynch mob and proceed to devastate the premises. Krasznahorkai’s parallels with southern gothic fiction are as striking as those with other eastern European allegories, yielding cadenced prose as monotonously grim as Thomas Bernhard’s. The long takes following characters — the structural equivalent of the novel’s Faulknerian sentences, though the content recalls Beckett’s comedy of inertia — underline our easy complicity with these monsters, and the actors, including Hanna Schygulla in a welcome comeback, are riveting. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 20, 2002). And highly recommended reading: Giles Harvey’s excellent long review of Pawlikowski’s Cold War in the January 2019 issue of Harper’s. — J.R.

Pawel Pawlikowski (Last Resort) is clearly a filmmaker to watch, and he’ll appear at the festival to discuss these four English TV documentaries. From Moscow to Pietushki (1990, 45 min.), a portrait of writer Venedikt Yerofeyev, samples his work (especially the eponymous novel) in voice-over by Bernard Hill and shows how and why Yerefeyev became the patron saint of Russian alcoholics during the end of the Khrushchev era. A survivor of throat cancer, Yerefeyev needs mechanical assistance to speak, but his dry gallows humor survives intact. The hilarious Dostoevsky’s Travels (1991, 45 min.) trails the novelist’s great-grandson Dmitri, a tram driver from Saint Petersburg, as he travels around Germany hoping to find a Mercedes he can afford. He can’t speak or understand much German, and the people he encounters, though mostly friendly, seem as clueless about his ancestor as he is. (Explains one speaker at a meeting of the Dostoyevsky Society, Most people here are only familiar with Dostoyevsky through the film Anna Karenina.) Tripping With Zhirinovsky (1995, 40 min.) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1989). — J.R.

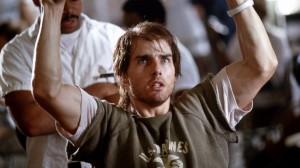

Ron Kovic’s autobiography, which recounts his conversion from patriotic enlisted marine to crippled demonstrator against the Vietnam war, isn’t a very literary book, although it uses some very literary devices (frequent time leaps, switches between first and third person) to approach the intensity of the traumas it deals with. Oliver Stone’s well-intentioned but faltering 1989 adaptation, scripted by Stone in collaboration with Kovic and starring Tom Cruise, eschews this approach for an episodic linear plot that doesn’t allow us to see Kovic’s conversion develop with any complexity. (As he showed in Platoon, Stone knows a lot about fighting in Vietnam, but he knows much less about being an antiwar activist, which is equally important to Kovic’s story; the movie’s demonstrations tend to be as blurry and as cliched as its nostalgic evocations of the American dream.) Stone’s unfortunate penchant for psychologizing leads to a number of murky suggestions here, such as the notion that Kovic’s warmongering instincts were somehow tied to the refusal of his mother (Caroline Kava) to let him read Playboy. Worst of all, the movie’s conventional showbiz finale, brimming with false uplift, implies that the traumas of other mutilated and disillusioned Vietnam veterans can easily be overcome if they write books and turn themselves into celebrities. Read more