Published in Contrappasso, coedited by Matthew Asprey Gear and Noel King, in 2015. — J.R.

AN INTERVIEW WITH

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

Matthew Asprey Gear

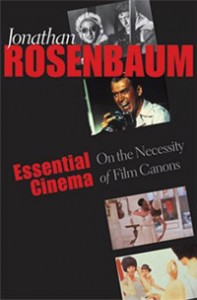

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM is one of the most respected film critics in the United States. His many books include Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980/1995), Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995), Movies as Politics (1997), Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films You See (2000), Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004), and Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinéphilia: Film Culture in Transition (2010).

Rosenbaum has also been a lifelong champion of Orson Welles. Many of his writings on Welles are collected in Discovering Orson Welles (2007). He also edited and annotated This Is Orson Welles (1992/1998), an assembly of the legendary Peter Bogdanovich-Orson Welles interviews.

This brief conversation for Contrappasso, an update on Rosenbaum’s recent activities, was conducted by email in early 2015.

ASPREY GEAR: Jonathan, you retired from your position as film critic at the Chicago Reader in 2008. You now teach, write as a freelancer, and republish your voluminous archive at www.jonathanrosenbaum.net. How have your priorities changed since 2008?

ROSENBAUM: I’m no longer a regular reviewer, and therefore I no longer have to keep up with current releases and see films that I don’t want to see (the majority of what I was seeing at the Reader). Read more

From Film Quarterly, Fall 2008 (Vol. 62, No. 1). I’ve more recently watched Curtis’s powerful and eye-opening Bitter Lake (2015) as well as his somewhat more paranoid HyperNormalisation (2016), also readily available for free on the Internet, which generally maintain the high level of the work discussed here. And I’m currently about halfway through Can’t Get You Out of My Head, which premiered on BBC last month. Some of my ambivalences about Curtis’ tendency to work both sides of the street — to criticize conspiracy theories and use them as seductive bait almost simultaneously; and to employ intellectual, non-intellectual, and even anti-intellectual means of persuasion in his storytelling with equivalent amounts of fervor — remain, but he’s too provocative to ignore.– J.R.

There’s been a steady improvement over the course of the three most recent BBC miniseries of Adam Curtis — The Century of the Self (2002, four hour-long episodes), The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear (2004, three hour-long episodes), and The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom (2007, three hour-long episodes) —- both in terms of their intellectual cogency and persuasiveness and in terms of the interest of Curtis’s developing, innovative style of filmmaking. Read more

Film Four Reasons Not to Trust Ten-Best Lists

One of the most cherished fantasies in the world of movies is that around this time every year we critics are all dying to think about the best films of the past 12 months — as if listmaking represented some particular populist need for consensus rather than the industry’s desire to resell goods that have already been sold to us again and again (or, in this neck of the woods, to presell goods that haven’t arrived yet).

I’ll admit that one list engenders another, and that once the game starts in earnest, every critic wants to be part of the discussion. But consider some of the drawbacks:

(1) Piles of movies getting released at the end of this year in such a manner that critics (and some audience members) don’t even have time to take them in, much less think about them. (Maybe that’s exactly what the studios want–snap judgment is another practice that serves the industry more than the audience.)

(2) Contortions by critics outside New York and Los Angeles who don’t want to come across as rubes and so vote for movies that most of their readers can’t see yet.

Read more

There seems to be a general agreement among cinephiles that Fritz Lang thought that Cinemascope was suitable only for filming snakes and funerals — despite the fact that Lang’s own Moonfleet (1955), shot in the related format of Metroscope, uses that rectangular shape quite effectively, as does the similarly anamorphic While the City Sleeps (1956).

But that wisecrack about snakes and funerals is more or less what Lang delivers while playing himself in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963), also shot in a ‘Scope format. Yet as Pierre Gabastan points out in the Autumn 2016 issue of the French quarterly journal Trafic (No. 99), this is a remark stolen from Orson Welles — specifically, from a French translation of an article by Welles (reprinted in the same issue of Trafic) that appeared in the weekly magazine Arts (no. 673, 4-10 juin 1958), one of the journalistic mainstays of Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette during this period, which stated that CinemaScope was ideal for funeral processions in long shot and snakes in close-up. As Gabastan plausibly argues, Godard must have remembered this line and asked Lang to deliver it as his own.

If so, there might have been a faint sense of getting even on Lang’s part. Read more

My summer 2020 column for Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Well before the coronavirus pandemic kicked in, I’d already started nurturing a hobby of creating my own viewing packages on my laptop. This mainly consists of finding unsubtitled movies I want to see, on YouTube or elsewhere, downloading them, tracking down English subtitles however and whenever I can find them, placing the films and subtitles into new folders, and then watching the results on my VLC player. The advantages of this process are obvious: not only free viewing, but another way of escaping the limitations of our cultural gatekeepers and commissars— e.g., critics and institutions associated with the New York Film Festival, the New York Times, diverse film magazines (including this one), not to mention the distributors and programmers who pretend to know exactly what we want to see by dictating all our choices in advance. (I hasten to add for the benefit of skeptics that my interest in subtitling unsubtitled movies has nothing to do with liking certain films because they’re neglected: I’ve been employing the same practice lately with some of the films of Carol Reed, largely because I like combining the pleasures of reading with those of film watching.)

Case in point: the great Ukrainian/Romanian/Russian/Soviet writer-director Kira Muratova (1934–2018), whose wild and amazing works have never reached the consciousness of most North Americans, can sometimes be joyfully accessed in this manner. Read more

Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards 2017

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Lucien Logette, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. Chaired by Paolo Mereghetti.

PERSONAL CHOICES

Lorenzo Codelli: Norman Foster’s Woman on the Run (1950, Flicker Alley, Blu-ray). A lost gem rescued by detective Eddie Muller’s indefatigable Film Noir Foundation

Alexander Horwath: Déja s’envolé la fleur maigre (Paul Meyer, 1960, Cinematek/Bruxelles, DVD) and Il Cinema di Pietro Marcello: Memoria dell’immagine (2007-2015, Cinema Libero/Cineteca di Bologna, DVD). Regarding the latter: with this cinematheque-style DVD, subtitled in English and French, one of the greatest contemporary filmmakers, whose work is still under-appreciated outside Italy, receives his rightful chance for global recognition.

Lucien Logette:

Tonka Šibenice (Karel Anton, 1930, Czech Republic, Národní filmový archiv/Filmexport Home Video, DVD)

One of the first Czech sound films. Like many great films of that era, it reflects several influences: expressionism, social realism, Kammerspielfilm, the art of Soviet photography, all used remarkably, without imitation. It contains all the great themes of the end of the silent period: the opposition between the city and the countryside, the misdeeds of modern society, frustrated loves ending in drama, themes served by an astonishing visual beauty.

Mark McElhatten: Kafka Goes to the Cinema (Munich, 4 DVD box set, Edition Filmmuseum). Read more

For Cineaste, Spring 2020. — J.R.

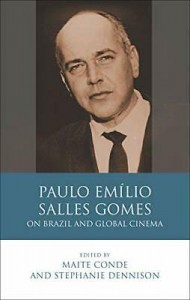

Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes

On Brazil and Global Cinema

Edited by Maite Conde and Stephanie Dennison.

Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018, 242 pp.,

Hardcover: $199.99, Kindle: $64.60, Paperback (from

University of Chicago Press): $68.00

Brazilian critic, film historian, and teacher Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes (1916-77) is principally known outside of Brazil as P.E. Salles Gomes, the author of the 1957 book Jean Vigo — not only a definitive biography, essential to Vigo’s posthumous rediscovery, first published in France (and translated from French to English in the early 1970s by the author), but also clearly one of the first major critical biographies of any filmmaker in any language. The editors of this volume, however, usually refer to him simply as Paulo Emílio, and picking up on their friendly Brazilian etiquette, I will follow suit.

$68.00 is an outrageous price for a paperback book less than 300 pages long, suggesting a volume intended only for well-funded libraries and professors with institutional perks to spare. But I’m also obliged to report that this first collection by a major and widely neglected figure in film studies redirects my thoughts about cinema like few other recent books. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 27, 2006). — J.R.

Death of a President **

Directed by Gabriel Range

Written by Simon Finch and Range

With Hend Ayoub, Brian Boland, Patricia Buckley, Jason Abustan, and Chavez Ravine

I dislike few buzzwords more than mockumentary, which even academics now use casually and uncritically. People often assume it’s a neutral descriptive term, but unlike pseudodocumentary — an honest and serviceable label — mockumentary leads many to conclude that the documentary form that’s being imitated is also being made fun of. Most of the works that get labeled mockumentaries are actually honoring the form, by using its techniques to make them seem more real.

According to Wikipedia, the term was first used by Rob Reiner while describing his own This Is Spinal Tap (1984), a popular spoof that led to many successors, including movies directed by Christopher Guest like Best in Show and A Mighty Wind. But these films weren’t so much mocking the documentary form as mocking documentary content. Of course there are films that mock documentary form much more directly, including Peter Watkins’s The Battle of Culloden, Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary, and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane and F for Fake. Read more

The longest chapter in my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Arden Press) — which only recently went out of print, though it’s still available from Amazon. I’m sorry that some of the illustrations aren’t of better quality. I’ve done a light edit on the text.

Considering that Benning by now probably has dozens of features to his credit rather than merely four, and that some of these are staggering achievements, I’m not at all sure if my judgments of three decades later would be the same. It’s also worth mentioning that I’ve written about a good many of his subsequent films, including (on this site) Landscape Suicide (1987), Used Innocence (1989), North on Evers (1992), Deseret (1995), Four Corners (1998), Utopia (1998), El Valley Centro (2000), his California Trilogy (2000-2004), Ten Skies (2004), One Way Boogie Woogie/27 Years Later (2005), and RR (2009), often at some length. It’s a pity that most of these films aren’t readily available, but I’m happy to report that the Austrian Film Museum (https://www.edition-filmmuseum.com/) , which published the first substantial book about James Benning in 2007, has launched the long-overdue project of restoring and releasing Benning’s work on DVDs — beginning with American Dreams (lost and found) (1984) and Landscape Suicide, in a two-disc set with a 20-page booklet, for 29,95 Euros, and followed by several more such packages. Read more

My column in Cinema Scope No. 82, Spring 2020. — J.R.

On “A Melody Composed by Chance…” — an excellent new audiovisual analysis of Jacques Demy’s Les demoiselles de Rochefort (1967) on the BFI’s Blu-ray of the film, written and narrated by Geoff Andrew and deftly edited by this disc’s producer Upekha Bandaranayake — I’m grateful to Andrew for correcting the gaffe in my booklet essay claiming that the film’s offscreen ax-murder victim is the Lola (Anouk Aimée) of Demy’s first feature, who subsequently turns up in Model Shop (1969); in fact, it’s the much older Lola-Lola of Josef von Sternberg’s first Marlene Dietrich feature. The other notable extras on this release include “feature-length” audio interviews with Demy (by Don Allen), Michel Legrand (by David Meeker), and Gene Kelly (by John Russell Taylor), Agnès Varda’s essential documentary Les demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993), and a fact-filled, critically acute audio commentary by Little White Lies’ David Jenkins — I especially like the way Jenkins cross-references this film with Varda’s underrated Le Bonheur (1965), another film that posits dark ironies behind the Hollywoodish dreams it celebrates.

***

I find it astonishing, really jaw-dropping, that Midge Costin’s mainly enjoyable Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound (2019), available on a UK DVD on the Dogwoof label, can seemingly base much of its film history around a ridiculous falsehood: the notion that stereophonic, multi-track cinema was invented in the 1970s by the Movie Brats — basically Walter Murch, in concert with his chums George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola — finally allowing the film industry to raise itself technically and aesthetically to the level already attained by The Beatles in music recording. Read more

Published by Santa Teresa Press (in Santa Barbara) in 1994 (twenty years later, this book is still available on Amazon) and reprinted in Discovering Orson Welles in 2007, along with the following introductory comments:

Critic Dave Kehr once said to me that encountering The Cradle Will Rock after The Big Brass Ring was a bit like encountering The Magnificent Ambersons after Citizen Kane. I appreciate what he meant — especially when it comes to this script’s nostalgia and its sharp autocritique compared to the more narcissistic and irreverent surface of its predecessor. But I hasten to add that this script, unlike The Big Brass Ring, is more interesting for its autobiographical elements than for its literary qualities. Perhaps for the same reason, writing an afterword about it was more difficult.

On the subject of Tim Robbins’s Cradle Will Rock,I’d like to quote excerpts from an article of mine that appeared in the Chicago Reader on December 24, 1999:

For the past seven months, ever since Robbins’s movie premiered in Cannes, friends and associates who saw it there have been warning me that I, as an Orson Welles specialist, would despise it. Writer-director Robbins does make the character of Welles (Angus MacFadyen) a silly boozer and pretentious loudmouth without a serious bone in his body — something closer to Jack Buchanan’s loose parody of Welles in the 1953 MGM musical The Band Wagon than a historically responsible depiction of Welles in 1937. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 2007). — J.R.

After the more complicated story lines of Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies, Hungarian master Bela Tarr boils a Georges Simenon novel down to a few primal essentials: a railway worker in a dank and decaying port town witnesses a crime while stationed on a tower and then stumbles into some of the resulting situations. It’s a film about looking and listening, with a suggestive minimalist soundtrack and ravishing black-and-white cinematography by German filmmaker Fred Kelemen. Tarr’s slow-as-molasses camera movements and endlessly protracted takes generate a trancelike sense of wonder, giving us time to think and always implying far more than they show. (As Tarr himself puts it, The camera is inside and outside at the same time.) The fine cast includes Tilda Swinton and Hungarian actress Erika Bok, who played in Satantango when she was 11 and is now in her early 20s. In Hungarian with subtitles. 135 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 2007). — J.R.

One of my all-time favorite films, this beautiful 12-minute short by Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep, The Glass Shield), made for French TV in 1995, is a jazz parable about locating common roots in contemporary Watts and one of those rare movies in which jazz forms directly influence film narrative. The slender plot involves a Good Samaritan and local griot (Ayuko Babu), who serves as poetic narrator, trying to raise money from his neighbors in the ghetto for a young mother who’s about to be evicted, and each person he goes to see registers like a separate solo in a 12-bar blues. (Eventually a John Handy album recorded in Monterey, a countercultural emblem of the 60s, becomes a crucial barter item.) This gem has been one of the most difficult of Burnett’s films to see. (JR) Read more

I devoted almost an entire page in my first book, a memoir, to this unsung obscurity, a low-budget comedy western that I saw in Florence, Alabama with my brother Alvin on November 14 or 15, 1951, when I was eight and he was six, on a double bill with Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Man from Planet X. I can very nearly classify this viewing as my first cinematic encounter with the avant-garde, by which I mean something akin to what J. Hoberman calls Vulgar Modernism — eight months after what might have been my first non-cinematic encounter with the avant-garde when I attended a Spike Jones concert one Sunday afternoon at the Sheffield Community Center. Bear in mind that I saw Skipalong Rosenbloom a full year before the first issue of Mad (the comic book) appeared and almost two years before I bought my first issue (no. 6, August-September 1953); this was also a full year before I saw Frank Tashlin’s Son of Paleface. It’s quite possible, of course, that I’d already seen one of Tex Avery’s cartoons by then, but if I had, this fact couldn’t be traced by the same methods of research that I employed in my memoir, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, which mainly involved combing back issues of the local Florence newspaper on microfilm for movie ads. Read more

Written at the request of Jae-cheol Lim, the editor of this Korean edition of Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (second edition, 2008), which was translated by Ahn Kearn Hyung and was published in late February 2016. Now that three copies of this hefty volume have just arrived in the mail (637 pages long, which is considerably more than the 449 pages of the original, apparently due in part to a different font size), this seems like a good time to repost the new Afterword. 2018 Postscript: I now regret including No Home Movie on my list, the only new selection I’ve changed my mind about. — J.R.

Afterword to the Korean Edition of ESSENTIAL CINEMA (January 2016):

The closer one comes to the present, the harder and more hazardous it becomes to compile a list of the best films. As I’ve recently pointed out elsewhere, one should consider the lengths of time between Jean Vigo’s death and the first appearances of Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante in the U.S. (thirteen years), or between the first screening of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and its recent appearances on Blu-Ray (forty-five years), and it becomes obvious that the popular custom of listing the best films of any given year is unavoidably a mythological undertaking derived more from faith than from any secure knowledge. Read more