From Video Movies (August 1984). -– J.R.

Out of the Blue

(1981), C. Director: Dennis Hopper. With Linda Manz, Dennis Hopper, Sharon Farrell, and Raymond Burr. 94 min. R. Media, $59.95.

When it was released, a friend wittily and succinctly described Out of the Blue as “Dennis Hopper’s Ordinary People.” Though this film didn’t start out as a Hopper movie (he signed on as an actor and took over direction after shooting started), it certainly has the Hopper flavor: relentlessly raunchy and downbeat, and informed throughout by the kind of generational anguish and sense of doom that characterizes both of his earlier films [Easy Rider and The Last Movie].

Hopper, one should recall, is a figure identified with the 1950s. He made his acting debut alongside James Dean in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Conceived as a kind of punk remake of Rebel set in a contemporary working-class environment, Out of the Blue centers around Cindy “CeBe” Barnes (Linda Manz), an alienated 15-year-old punk who perpetually mourns the deaths of Elvis Presley and Johnny Rotten. Her mother, Kathy (Sharon Farrell), is a junkie who works at a cheap restaurant; her father, Don (Hopper), is a former trucker and an alcoholic finishing off a five-year stint in prison when the film opens. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 15, 1989). — J.R.

TALES FROM THE GIMLI HOSPITAL

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Guy Maddin

With Kyle McCulloch, Michael Gottli, Angela Heck, Margaret-Anne MacLeod, Heather Neale, and Caroline Bonner.

Given the murky black-and-white photography, the fascination with repulsive medical details, the loony deadpan humor, the impoverished characters and settings, and the dreamlike drift of bizarre and affectless incidents, it’s difficult not to compare Tales From the Gimli Hospital with David Lynch’s Eraserhead. It’s also being distributed mainly (although not yet in Chicago) as a midnight attraction by Ben Barenholtz, the same man who launched Eraserhead on the midnight circuits a dozen years ago. Turning up here at the Film Center in Barbara Scharres’s “Films From the Lunatic Fringe” series, Tales From the Gimli Hospital isn’t an easy film to categorize, but invoking the name and weirdness of David Lynch gives you at least a rough idea of what to expect.

In many respects, Guy Maddin’s oddball independent Canadian production is distinctly different from Eraserhead. The sensibility at work here is neither painterly nor musical — the frames aren’t rigorously composed, and the eclectic editing rhythms are relatively stodgy and clunky — but steeped, rather, in the traditions of oral narrative and cinema of the late 20s and early 30s. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1990). — J.R.

This 1989 feature by Alejandro Jodorowsky is just as silly and pretentious as his previous El topo and The Holy Mountain, but it’s similarly watchable and fun in a campy, sub-Fellini sort of way — if only because of its dogged devotion to surrealist excess. (The Mel Brooks of vulgar surrealism, Jodorowsky’s basic principle is that if you throw 30 outrageous ideas at the audience, 2 or 3 are bound to make an impression.) It’s basically a sadomasochistic circus story about a crazed former magician (played at different ages by Jodorowsky’s sons Axel and Adan) whose father (Guy Stockwell) ran a circus and whose mother (Blanca Guerra) is a religious fanatic who worshiped an armless saint and lost her own arms. Many years after a traumatic (if, for Jodorowsky, characteristic) family incident that involves the mother’s mutilation and the father’s mutilation and suicide, the mother compels her son to become her lost hands, forcing him, among other things, to murder lots of women (Thelma Tixou, Zonia Rangel Mora, Gloriella). A deaf-mute the son loved as a child (Sabrina Dennison and Faviola Elenka Tapia) turns up later to redeem him. Scripted by Jodorowsky, Roberto Leoni, and Claudio Argento, and filmed in Mexico in English. Read more

From American Film (April 1982). — J.R.

The Film in History: Restaging the Past by Pierre Sorlin. Barnes & Noble, $21.50.

Feature Films as History edited by K.R.M. Short. University of Tennessee Press, $16.50.

Vietnam on Film: From “The Green Berets” to “Apocalypse Now” by Gilbert Adair. Proteus, $13.95.

What is a historical film? Sociologist and cultural historian Pierre Sorlin concludes a comparison between two French films about the French Revolution released during the mid-thirties — Abel Gance’ s Napoleon Bonaparte and Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise — with a succinct formula for his provocative working assumption in The Film in History. “A historical film,” he writes, “is a reconstruction of the social relationship which, using the pretext of the past, reorganizes the present.”

It’s an interesting notion to try out on all the films that we regard as historical. To get a proper fix on Reds, for instance, one has to consider not only the years 1915 to 1920, during which the portrayed events take place, but also the much more immediate past, during which the movie was being formulated and put together, and the present, during which it is being seen and understood. Thus the relatively short shrift paid in the film to class differences – a fundamental issue in John Reed’s life — can be ascribed in part to the basically middle-class orientation of the student revolts in the sixties, which have a lot to do with the way that we currently regard radical politics. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 22, 1990). — J.R.

One of the classiest and most experimental 3-D efforts from Hollywood — as well as one of the best MGM musicals of the 1950s that didn’t come from the Arthur Freed unit. Adapted by Dorothy Kingsley from the successful 1948 Cole Porter stage musical and directed by the underrated George Sidney, this 1953 feature does interesting things with mirrors, windows, and the relationship between stage and audience, playing on the differences between theatrical and film space and, paradoxically, exploiting 3-D as an artificial and antirealistic effect. Kathryn Grayson and Howard Keel play an estranged couple who uneasily join forces in a musical version of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, with much comic confusion between life and art. The cast (including Ann Miller, Tommy Rall, Bobby Van, Bob Fosse, and Carol Haney) and score are consistently pleasurable. 109 min. (JR)

Read more

Originally published in Moving Image Source (posted online as “Hidden Treasures”), July 17, 2008. — J.R.

Ever since I retired a few months ago from my 20-year stint as film reviewer for the Chicago Reader, perhaps the biggest perk of all has been freedom from the chore of having to keep up with new movies. In practice, this translates into more free time to keep up with old movies. So returning to one of my favorite annual pastimes, Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna — a festival that caters to people devoted to seeing old films in good prints — seemed only natural. Its 22nd edition, the fourth one I’ve attended, was especially rich.

Held in the oldest university town in Europe — hot and muggy this time of year, and full of labyrinthine back streets — the eight-day event mainly takes place at three air-conditioned cinemas during the day and at the Piazza Maggiore every evening, where the grand public shows up for outdoor screenings. (There’s also a jury that I’ve served on in previous years selecting the best restorations on DVD.) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). This is available on Blu-Ray from Twilight Time. — J.R.

Francois Truffaut’s free adaptation of Cornell Woolrich’s masochistically doom-ridden Waltz Into Darkness, in ‘Scope and color, yields an unsuccessful but sympathetic exploration of the filmmaker’s underrated darker side. A wealthy tobacco planter (Jean-Paul Belmondo) sends for a mail-order bride, and the mysterious lady who turns up is not the woman he was led to expect but Catherine Deneuve. Stately and languorous in its dreamy melancholy, though never entirely convincing, this 1969 picture is full of movie references — even the cabin at the end of Truffaut’s own Shoot the Piano Player figures centrally. But perhaps its ultimate justification is that of Truffaut’s other morbid films, such as The Bride Wore Black, The Story of Adele H, and The Green Room: a doomed romantic protagonist (in this case Belmondo) who goes the limit. In French with subtitles. 123 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1999). — J.R.

Not bad for a toy commercial, and the SF settings, however familiar, are even more impressive than the gadgets and beasties. The casualties are narrative momentum (at least compared to episode four) and the actors — Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman, Frank Oz, Samuel L. Jackson, Ray Park — who are stilted and humorless but can’t be blamed, since George Lucas’s mind was on the digital effects. (An overgrown Jamaican reptile of indeterminate gender named Jar Jar Binks has been created specifically to tell the audience when it’s OK to laugh.) At great expense, Lucas has finally succeeded in duplicating his low-budget models (mainly serials and westerns of the 50s) in emotional range as well as in action. The digital effects help him realize this sincere aim, but the campy whiffs of pseudoprofundity are strictly analogical and exclusively the writer-director’s, and in a way they’re every bit as charming as the simplicity. PG, 133 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43. No. 510). — J.R.

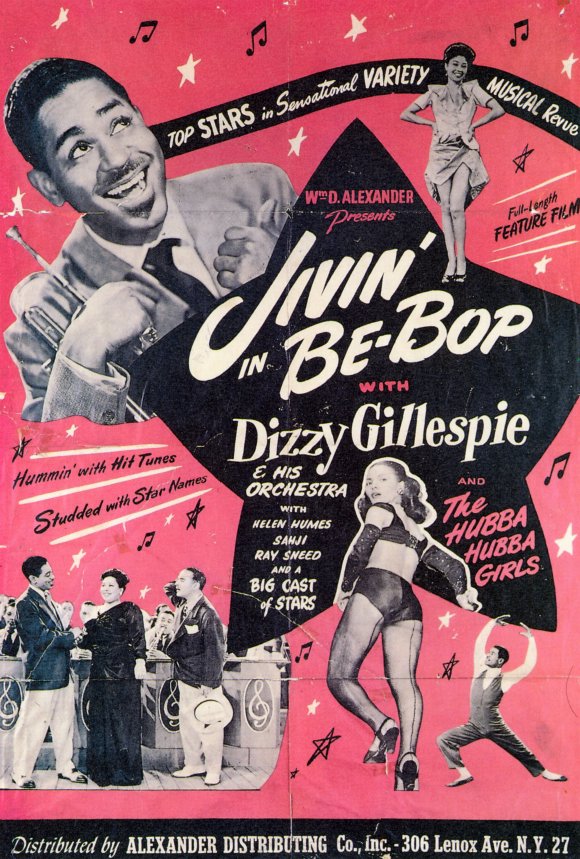

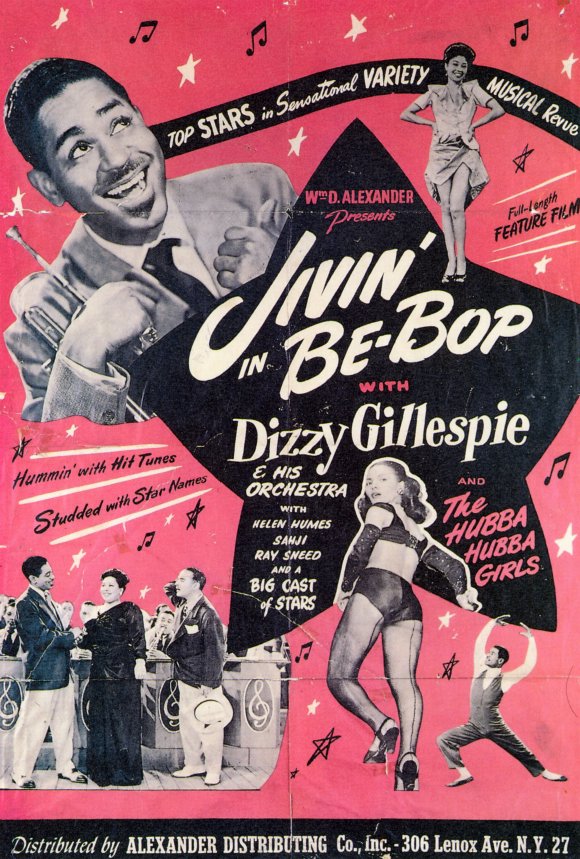

Jivin in Be-bop

U.S.A., 1947Director: Leonard Anderson

Dist—TCB. p.c—Alexander Productions. p—William D. Anderson. sc—Powell Lindsay. ph—Don Malkames. ed—Gladys Brothers. m/songs–(including) “Salt Peanuts”< “I Waited for You”, “Dizzy Atmosphere” by Dizzy Gillespie, “Bop-a-Lee-ba” by Dizzy Gillespie, John Brown, “Oop Bop Sh-‘Bam” by Gil Fuller, Dizzy Gillespie, Roberts, “Shaw ‘Nuff” by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, “A Night in Tunisia” by Dizzy Gillespie, Frank Paparelli, “One Bass Hit”, “Things to Come” by Dizzy Gillespie¸ Gil Fuller, “Ornithology” by Charlie Parker, Benny Harris,” “E Beeped When He ShouldaBopped” by Dizzy Gillespie, Gil Fuller, John Brown, “Crazy About a Man”, “Boogie in C”, “Boogie in D”, “Shoot Me a Little Dynamite Eight”, “Grosvenor Square”. sd—Nelson Minnerly. with—Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra, Sahji, Freddie Carter, Ralph Brown, Helen Humes, Ray Sneed. San Burley and Johnny Taylor, Phil and Audrey, Johnny and Henny, Daisy Richardson, Pancho and Dolores, Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Ray Brown, Kenny “Pancho” Hagood. 1,160 ft. 60 min. (16 mm.)

A continuous series of musical performances and dance routines shown on stage, without a visible audience, occasionally interspersed with comic repartee between Dizzy Gillespie and an emcee identified variously as “Peanut Head” Jackson and Burt. Read more

From Film Quarterly, Spring 1984. -– J.R.

AMERICAN DIRECTORS

Two volumes. Edited by Jean-Pierre Coursodon, with Pierre Sauvage. New York: McGraw Hill, 1983. $21.95 per volume cloth, $11.95 per volume paper.

On the whole, Jean-Pierre Coursodon’s 874-page, two-volume American Directors is closer in genre to Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary than it is to Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema. Like both predecessors, it is an encyclopedia of opinions first and facts second — although, to its credit, it has many more facts per entry (in filmographies and career summaries) than either of the earlier monoliths. Like the Roud and unlike the Sarris, it attempts exhaustive surveys rather than suggestive critical miniatures, and is authored by many hands. Coursodon wrote 66 of the 118 essays and co-editor Pierre Sauvage, who furnished all the filmographies, contributed 13; the remaining 39 are by 20 other writers.

Again like the Roud, the Coursodon stands or falls as a compendium more than as a book with a sustained viewpoint; consecutive or continuous reading is neither recommended nor viable. Overall, the criticism is homogeneous, perhaps too much so: the standard auteurist form of career survey — already a bit fossilized — as developed out of Coursodon and Bertrand Tavernier’s Trente ans de cinéma américain (1970) and The American Cinema (1968) is so predominant here that other critical persuasions of the past two decades might as well have never existed. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 24, 1989). — J.R.

LOOK WHO’S TALKING

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Amy Heckerling

With Kirstie Alley, John Travolta, George Segal, Olympia Dukakis, Abe Vigoda, and the voice of Bruce Willis.

The biggest surprise in the film industry this season has been the box office performance of what is generally known as “the talking-baby movie.” Last month, only a week after a Variety reviewer plausibly predicted that this “yuppie-targeted programmer is destined for a short life in theaters, and its video future seems likewise limited,” Look Who’s Talking leapt to the top of the national charts, where it has remained ever since.

Having only just caught up with Look Who’s Talking, I must confess that I found the voice-overs of the talking baby, delivered by Bruce Willis, to be the silliest and least engaging aspect of the picture, although the audience I was seeing it with seemed to feel otherwise. I was probably biased by unpleasant childhood memories of the “Speaking of Animals” shorts — a rather odious series made by Jerry Fairbanks for Paramount during the 40s, which consisted of live-action animals with animated mouths spewing out wisecracks, usually in response (if memory serves) to the gag setups of the offscreen narrator. Read more

A Chicago Reader capsule (1990). — J.R.

I saw the Living Theater’s legendary production of Jack Gelber’s play (directed by Judith Malina) three times during its initial run in the early 60s, and no film adaptation half as long could claim its raw confrontational power. Echoing The Lower Depths and The Iceman Cometh, it’s about junkies waiting for a fix (among them a performing jazz quartet with pianist-composer Freddie Redd and alto sax Jackie McLean), and spectators were even accosted in the lobby by one actor begging for money. Shirley Clarke’s imaginative if dated 1961 film uses most of the splendid original cast (Warren Finnerty is especially good), confining the action to the play’s single run-down flat. It’s presented as a pseudodocumentary; the square neophyte director, eventually persuaded to shoot heroin himself, winds up focusing his camera on a cockroach. The film retains the same beatnik wit that the play effectively distilled, as well as a few scary shocks, and the music is great,. With Carl Lee, Garry Goodrow, and Roscoe Lee Browne. 105 min. (JR)

Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 509). — J.R.

Hollywood Cowboy

U.S.A., 1975

Director: Howard Zieff

Cert–A. dist–ClC. p.c–MGM. A Bill/Zieff production. p–Tony Bill. p. manager–Clark L. Paylow. asst. d–Jack B. Bernstein, Alan Brimfleld. sc–Rob Thompson. ph–Mario Tosi. col–Metrocolor. ed–Edward Warschilka. a.d–Robert Luthardt. set dec–Charles R. Pierce. m-Ken Lauber. m. sup–Harry V. Lojewski. special musical artists–Nick Lucas, Roger Patterson, Merle Travis. cost–Patrick Cummings. choreo--Sylvia Lewis. Titles/opticals–MGM. sd–Jerry Jost, Harry W. Tetrick. sd. effects–John P. Riordan. l.p–Jeff Bridges (Lewis Tater), Blythe Danner (Miss Trout), Andy Griffith (Howard Pike), Donald Pleasence (A. I. Nietz), Alan Arkin (Kessler), Richard B. Shull (Stout Crook), Herbert Edelman (Polo), Alex Rocco (Earl), Frank Cady (Pa Tater), Anthony James (Lean Crook), Burton Gilliam (Lester), Matt Clark (Jackson), Candy Azzata (Waitress), Thayer David (Bank Manager), Marie Windsor (Woman at Nevada Hotel), Anthony Holland (Guest at Beach Party), Dub Taylor (Nevada Ticket Agent), Raymond Guth (Wally), Wayne Storm (Zyle), Herman Poppe (Lowell), William Christopher (Bank Teller), Jane Dulo (Mrs. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1996). — J.R.

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s major work (1990) consists of ten separate films, each running 50-odd minutes and set mainly around two high-rises in Warsaw. The films are built around a contemporary reflection on the Ten Commandments—specifically, an inquiry into what breaking each of them in today’s world might entail. Made as a miniseries for Polish TV before Kieslowski embarked on The Double Life of Veronique and the “Three Colors” trilogy, these concise dramas can be seen in any order or combination; they don’t depend on one another, though if you see them in batches you’ll notice that major characters in one story turn up as extras in another. One reason Kieslowski remains controversial is that in some ways he embodies the intellectual European filmmaking tradition of the 60s while commenting directly on how we live today. The first film, illustrating “Thou shalt have no other gods before me,” is about trust in computers; the often ironic and ambiguous connections between most subsequent commandments and their matching stories tend to be less obvious. (One of the 60s traditions Kieslowski embodies is that of the puzzle film, though he takes it on seriously rather than frivolously, as part of his ethical inquiry.) Read more

From the English magazine Creative Camera (No. 1, 1990). This is mainly derived from a catalog that was put together about Klein for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis the previous year, consisting of an essay and interview which will eventually be posted here separately. -– J.R.

One of the limitations of conventional film history, with its subdivisions of schools and movements, is that many interesting filmmakers who are unlucky enough to exist apart from neat categories tend to disappear between the cracks. The case of William Klein, whose film work has received negligible commentary (especially in English), can partially be explained by pointing to the things he is not — or at least not quite.

He is not quite “American” — although he was born in New York City in 1928, grew up near the intersection of 108th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, and has devoted a substantial part of his film work to American subjects. He is not quite “French” — although he moved to Paris in 1948 to study painting with Fernand Léger and has been based there ever since. He began making films in the 1950s, around the same time the French New Wave was gaining prominence, and he might provisionally be regarded as a member of the so-called Left Bank group, which included Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnes Varda. Read more