Researching Iranian cinema, even contemporary Iranian cinema, can sometimes be a dicey undertaking, in part because of the variant spellings of names and even a few film titles. I thought enough of Seyyed Reza Mir-Karimi ‘s first feature, The Child and the Soldier (2000), to include it on my list of my 1000 favorite films, included as an appendix in my 2004 collection Essential Cinema. And Fred Camper thought enough of his second feature, Under the Moonlight (2001), to begin his capsule review for the Chicago Reader by writing, “A refreshing version of Islam in which charity and justice are more important than rigid adherence to rules.” And now that I’ve seen his latest feature, which is Iran’s official entry for this year’s Academy Awards, Today — or Today!, as it appears to be written on the screen in Persian -– it’s clear that this director qualifies as a master. But now (today) his name is mainly given in Western sources as Reza Mirkarimi, without the Seyyed or the hyphen, so when I looked up this name on my own web site, I could find nothing. So it seems both ironic and ironically appropriate that the most ethical and humanist cinema we can find in the world today both engages directly with and is often confounded by our ignorance about the world we inhabit.

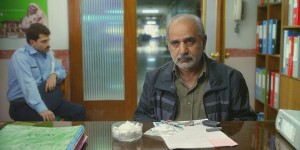

Part of Mirkarimi’s mastery, combined with his remarkable cast and his elegant mise en scène, is a matter of what he chooses not to show (or tell), as in the opening, precedits sequence, which provides us with a false lead — focusing on a male passenger in the back seat of a taxi, chattering on his mobile, en route to a courthouse — until the offscreen driver, who subsequently proves to be the film’s central character, announces that he won’t drive him any further. It doesn’t take us very long to figure out why (the guy is a glib asshole), but this driver is a taciturn character who often avoids conversation, even when he’s asked questions, as we subsequently discover when he picks up his next passenger (see above still), a desperate, pregnant woman who’s clearly undergoing a lot of pain and stress. And his involvement with this woman and her fate is what continues to occupy us for the remainder of the picture.

The title of the film seems both ironic and appropriate. Ironic because the surface of the film’s action — mainly the everyday events in a poorly equipped hospital — recalls the Italian neorealism of over half a century earlier. But appropriate because all the things that we don’t know about the driver, who’s immediately assumed by the staff to be the woman’s husband, and who says nothing to contradict this assumption, becomes almost as important to us as all of the things we observe about him and the hospital and the woman (none of which or whom we know much about either). Existentially, our ignorance forces us to be observant and to decide what’s important and unimportant.

In some respects, the plot’s departure as well as its conclusion may remind us of one of the masterpieces of the “first” Iranian New Wave, Ebrahim Golestan‘s powerful 1965 Brick and Mirror (also known as The Brick and the Mirror, to confound our indexes and Google searches, and woefully unavailable on DVD, though posted with English subtitles on YouTube), whose hero is a much younger cab driver whom we know much more about. Golestan’s title comes from the classical Persian poet Sa’adi, who wrote, “What the old can see in a mud brick, youth can see in a mirror,” and in a way this statement can be applied to Mirkarimi’s cab driver as well as Golestan’s — not to mention the young woman each driver picks up. But the beauty of Today — and, one could argue, the major ethical challenge of living in the world today — resides in how we’re asked to cope with our ignorance. [10/18/14]

Postscript [10/19/14]: A message from Parvis Jahed: Dear Jonathan, I’ve read your review of Reza Mirkarimi’s Today. I haven’t seen the film yet but I liked the way you compared the film with Golestan’s The Brick and the Mirror. By the way there is minor mistake about the Persian poem in your text. It’s attributed to Sa’adi by mistake in various sources but in my interview with Golestan, he clarified that the poet is unknown but it [might be] attributed to Attar. With all my respect, Parvis.