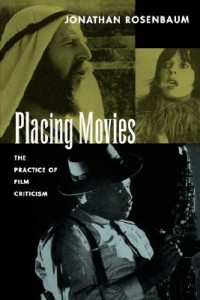

This is the Introduction to the fourth section of my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (University of California Press, 1993).– J.R.

This is the most rebellious and contentious section of the book, and because of this, some readers will regard it as the least practical or viable. Before you make up your own mind about this, however, I’d like to ask you to examine precisely what you mean by “practical” and “viable.” Do you mean most likely to change the world, or do you mean most likely to affect the majority? If in fact you believe that the likeliest way to change the world is invariably to affect the majority, then it might be beneficial to look at that premise a little more closely and see if it always holds up.

Speaking from my own experience, the times when I’ve reached the greatest number of readers at once — writing features in the pages of magazines like Elle and Omni — are the times when my point of view has had the least amount of effect. How do I know this? I can’t exactly prove it, but a writer’s sense of his or her impact comes from feedback, and I’ve had virtually no feedback at all on the pieces I’ve written for mass-market magazines.

It might be argued that my contributions to Elle and Omni have been too brief and occasional to carry much significance. What, then, of my regular stints on Oui (1974–1975) and American Film (1979–1980), my principal means of self-support the year before I moved from Paris to London and during the last stages of my work on Moving Places, respectively? In both cases, where I was often accorded more leeway than I had at Elle and Omni, the discernible impact of my pieces was again almost nil. This is not to say that I necessarily regarded my assignments for these magazines as hackwork. (Truthfully, sometimes I did and other times I didn’t.) Either way, whether the editorial changes made in my copy were negligible or substantial, the published results, in my opinion, never carried much weight — which is why none of these pieces is included in this collection. (Theoretically, this could have turned out differently. My piece on Barthes in the first section, for instance, was originally commissioned by American Film and wound up in Sight and Sound only because the American Film editor decided against running it.)

As the result of such experiences, I usually feel that it’s better to affect a few people very strongly than to affect a lot of people superficially. This is fundamentally at odds with the numbers game that permeates much of American thought — the assumption that not only can everyone be President, but anyone who doesn’t try to become one is a damned fool. A few friends and relatives, for instance, believe that my job as a film critic for the Chicago Reader is “good” only in the sense that some day it might lead to something really “good,” like being film critic for The New Yorker, when my response to this is that many of the pieces I’ve written for the Reader — which are fundamentally the pieces I’ve wanted to write — could never have been written for The New Yorker. In fact, when it comes to prestigious and powerful institutions like The New York Times, I wonder how much individuality really counts in the long run: Vincent Canby may be less square than Bosley Crowther, his long-term predecessor, but the Times is so much stronger than either of them that whoever gets the job of film critic there is likely to wind up writing with the same values and in the same way for the same audience, in the long run.

Admittedly, sometimes a fact or opinion can have weight and influence only after it becomes mass-market. I’m happy to report that a direct consequence of “OTHELLO Goes Hollywood” — written for the Chicago Reader and reprinted in part 2 — is that the monks’ chants that were removed from the film’s opening scene in the so-called “restored” version were themselves restored to this version on video and laserdisc. I suspect, however, that this happened largely because my observation was picked up by a few national writers, such as Todd McCarthy in Daily Variety; if it had remained only in the Reader, it may have had no lasting effect.

To greater or lesser extents, the pieces in this section argue on behalf of minority positions that I don’t expect most readers to share or adopt. This may sound defeatist to some, but only if consensus criticism of the sort that is commonly practiced is viewed as the ideal. In the case of my defense of HARDLY WORKING, it’s worth noting that Jerry Lewis himself has called it his worst film — an opinion I disagree with — and that the movie has been eliminated from some retrospectives of his work, perhaps at his own request.

Speaking for myself, the critics who generally affect me the most aren’t necessarily the ones I most agree with or with whom I most identify. Contrary to the rising popularity of both tribalism and “targeting” on a worldwide level — which would dictate, if I were to go along with it, that I assiduously search out middle-aged heterosexual southern Jewish film critics to read and befriend — I can’t see much profit in looking exclusively for duplications of one’s own positions, however comforting and validating it may be at times to find them. Although some compatibility of opinions obviously helps one to form a feeling of trust for some reviewers, it’s rare that a feeling of total accord on a given subject will stimulate any further thought; more often its effect is to stop a line of thinking dead in its tracks.

***

It probably isn’t coincidental that this section is the one containing most Soho News pieces, because the year and a half when I was writing regularly for this small-time alternative to the Village Voice — starting in May 1980 and concluding in November 1981 — is the period when my writing was most contentious as well as combative. Apart from serving as film reviewer for that weekly (most often, alternating with Veronica Geng as the first-string critic), I had my only regular stint to date as a book reviewer — a kind of work I regret I haven’t had subsequent opportunities to do except sporadically. It’s a period that overlapped with the publication of Moving Places in fall 1980 — a formative experience that undoubtedly made me more assertive, especially once it became clear to me that the attention I had hoped the book would get was not forthcoming.

The premium placed on physical space in Manhattan has always seemed to me to have a lot to do with the way that people treat one another on that island. In fact, every stage of my stint at the Soho News seemed to reflect that fact. I was initially brought in as a writer at the suggestion of Richard Corliss — the paper’s former first-string film critic, who had just left for Time — and the first suggestion of the arts editor, Tracy Young, was that I be used to cover experimental films as a way of forcing out another critic, who had been covering that beat on the paper for some time. During that same period, I should add, instances of what I considered to be that critic’s arrogance and intolerance had already prompted two sarcastic letters from me that had both been published. But even though this critic struck me as embodying, along with some more valuable qualities, the epitome of provincial New York turf mentality, I made it clear to Tracy at the outset that I didn’t see how it was necessary to force her out of the paper —surely there was room for both of us. So she stayed on; but when Tracy offered her the same invitation in reverse a year and a half later — reviewing experimental films as a way of forcing me out — she took it without blinking. (The turning point came when Tracy insisted that this critic would be perfectly capable of writing an “unbiased” review of a feature by her former husband, which I incidentally liked more than she did; I still recall my bitter amusement over the resulting piece, which failed to mention the film’s lead actress — the director’s current wife — even once.)

In between those two events, I must confess that Tracy granted me more freedom than any other editor has before or since, with the possible exception of Corliss at Film Comment. She wound up publishing nearly all of the seventy or so pieces I wrote for her, usually with minimal editing, and the one portion of a piece she rejected (after provisionally approving it in principle) — in praise of a film that at that point had failed to receive any public showings in New York, Straub/Huillet’s FROM THE CLOUD TO THE RESISTANCE — was understandable given the consumerist nature of the paper’s art section.*

_____________________________________________________________

*The piece as a whole, entitled “Transcendental Cuisine,” made its polemical point by interrupting my reviews of the usual weekly trash to talk about a movie that my readers couldn’t see, which I had just shown in a course I was teaching at NYU. Tracy kept the trash reviews and discarded the rest, although over a year afterward, at the suggestion of Straub himself, I included the original piece, complete with the trash reviews, in an extensive monograph I edited to accompany a Straub/Huillet retrospective at the Public Theater. When I tried to reprint this piece in my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Arden Press, 1983), my editor, Fred Rainey, refused to let me reprint the trash reviews in the middle of the piece, with the result that my comments in the book proved to be as truncated as those in Soho News — once again because of the dictates of consumerism.

An even more sobering lesson in consumerism and rigid formats came when I discovered that both The New Yorker and the Village Voice were unwilling even to acknowledge in their listings that the Stranb/Huillet retrospective included eleven important films by other filmmakers selected by Straub and Huillet — one of them, incidentally, a feature that was receiving its U.S. premiere (Luc Moullet’s A GIRL IS A GUN). Typically, a letter of complaint about this to the Voice went unprinted, which shouldn’t have surprised me: few New York publications will print any letters criticizing their editorial positions.

Why Tracy eventually changed her mind about me and forced me out of the paper is not a matter that has ever been explained to me — nor was it a matter I felt I could ever ask her about. Indeed, the way I learned that I was no longer working for the paper—practically my only means of support at the time — was discovering that I could no longer reach her on the phone at her office. When I finally called her at home — she had given me her unlisted number months before — her only clarification was to tell me I was fired and to ask me not to call that number again.

Despite the lack of any explanation, I can think of at least two factors that probably played some role in my dismissal. One was the fact that the paper itself was in the process of going under and didn’t last very long after I left. And another, I strongly suspect, was the cumulative effects of my combativeness in print. This included some sarcasm about South African gold mines being involved in the sponsoring of a festival of British films (which may have been especially imprudent given the Afrikaner ownership of the Soho News at the time); an attack on the New York Film Festival for refusing to invite me to any of its parties for three years in a row — particularly galling after I had sacrificed most of a holiday in order to oblige Corliss by writing a piece for Film Comment about their opening night film (A WEDDING ) — which prompted an angry letter from Richard in the following issue, accusing me of both paranoia and ingratitude; and, what may have been the coup de grace, a prominently featured article, “Playing Oneself,” which was essentially an argument for the ethical superiority of LIGHTNING OVER WATER over MY DINNER WITH ANDRÉ — and which contained a key sentence about the writer and costar of the latter film, Wallace Shawn, which later was quoted in Esquire: “I’ve known Wally Shawn intermittently over a 22-year period, and he’s just about as nice as anyone can possibly be to someone he regards as a social inferior.”

When Wally and I had been classmates at boarding school, he had been the only other student there who had asked to read my first novel. But when it came to getting his responses, I had to go around to his family apartment to see if he was there rather than phone him, because he refused to give me his phone number — a privilege he accorded then only to classmates he regarded as his social equals. Knowing that Tracy worshiped at the shrine of The New Yorker, whose editor in those days was Wally’s father (an immensely kind and courteous man, I should add, who’d never shown to me any of Wally’s cruelty) — and that Wally himself, who had reluctantly agreed to let me interview him (but only if he brought along André Gregory, his costar), had tried in vain afterward to get the paper to run another piece about his film —leads me to reflect on how blatantly I was playing with fire. For whatever it’s worth, I still don’t think that anything I wrote in the piece was unfair or unethical — my personal biases in the matter were established at the outset, and part of my motivation was defending Wim Wenders against some unfair charges that had been lodged against LIGHTNING OVER WATER elsewhere. But the fact that I was broaching at all the matter of Wally’s privileged status at The New York Times — which had mercilessly trashed Wenders’ film, as it would later trash his subsequent THE STATE OF THINGS even more unfairly — was clearly violating a sacrosanct taboo.

It’s hard for me to evaluate this fearlessness and recklessness a dozen years later, since I’m no longer temperamentally disposed to wage such battles on the same terms today, but the ugliness of the social climate I was swimming through at the time certainly played a part in my rage. As one indication of this climate, I can recall a phone conversation I had with an editor at American Film in 1980, over a year before I left Soho News, which he opened by saying that he was sorry to hear I’d been fired. After I revealed to him that he was mistaken, he wouldn’t tell me who his source for this misinformation was, but after a bit of detective work, I was able to uncover both the source and the basis for the story. The source was another critic whom I had regarded up to that point as one of my closest and most loyal friends. The basis was that still another critic, a protégé of Pauline Kael’s who was eager to have my job, had heard that Pauline was having lunch with Tracy, and had let his eagerness and imagination run amok — telling another Kael protégé I’d already been fired and he’d already been hired, or words to that effect. I never learned the full extent of this chain reaction, but the “news” of the second protégé eventually reached my friend, who then informed not me but a magazine editor we both knew in Washington, D.C., about it. I should add that everyone involved in this little intrigue with the exception of myself — the editor, my friend, both protégés, and my informant — are today nationally known figures who write for highly respected publications with many millions of readers.

To me, the whole story represents the world of New York film critics in a nutshell and may help to account for the less measured tone adopted in some of my writing from this period. It also helps to explain why I don’t harbor many regrets about no longer working in New York. By the time I moved to the west coast in 1983, I virtually felt I’d been run out of town on a rail. Many colleagues were even refusing to say hello to me on the street, though it’s hard for me to see even today how my gadfly instincts had done their careers any appreciable harm. Fortunately, I still had a good many friends in the city; in fact, I continue to have more friends in New York than anywhere else in the world — but not the sort of professional contacts that would make me readily employable there.

Reflecting back on all the critical things I’ve had to say in this book about the New York film world, I should stress that many of the same problems may be even more prevalent in relation to theater. Ultimately these problems should be viewed as sociological rather than as the personal failings of individuals. The pertinent question is not why people who wish to get ahead in New York are obliged to flatter and whitewash those in positions in power, because clearly this situation exists everywhere else to some extent. What needs to be asked is why this is so much more the case in New York than it is elsewhere, with the result that intellectual candor in some areas becomes virtually impossible without unpleasant social consequences. I suspect that some critics would differ with me on this point, but I believe it is so much a fact of life that most New York critics have internalized it, and the few who haven’t will know exactly what I’m talking about. If Georgia Brown in the Village Voice dares to question some of the bloc-voting of the New York Film Critics Circle or make fun of David Denby for declaring that even God would be frightened by JFK, she can undoubtedly expect to be treated like a pariah in some quarters for such unthinkable impertinence and rudeness — which is perfectly okay to display toward out-of-towners and filmmakers, but not toward one’s more prominent colleagues (which can include programmers as well as critics). All things considered, it would be far easier to dismiss the entire European left in the pages of an alternative weekly — no one will penalize you for the presumption (and it’s been done before) — than it would be to make fun of the silly notions of a single local media honcho.

In my introduction to part 1, I noted my initial surprise that individuals a lot more powerful than myself could be so unforgiving about any criticisms made of their work. Perhaps New York’s peculiar restraints and self-censorships offer a partial explanation. If any intellectual challenge to those in power is deemed inadmissible to the “free” exchange of ideas, this surely can’t help the confidence of these people in the long run, because they know their safety from such challenge is achieved only through an atmosphere of repression. No wonder they’re so touchy.