From Sight and Sound (June 2011). Portabella continues to be the most flagrantly unseen and overlooked of major contemporary filmmakers, for reasons suggested in this sketch. — J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum voyages into the elusive and intriguing worlds created by Spanish filmmaker Pere Portabella

Among the lost continents of cinema — major films and artists that have perpetually eluded our grasp because they fall outside the usual institutional frameworks that we depend upon to ‘keep up’ with cinema — there are few contemporary figures more neglected than Catalan filmmaker Pere Portabella.

Born into a family of industrialists in Barcelona in 1929, Portabella has remained closely tied to that city’s art scene for most of his life, especially as a patron and friend of other Catalan artists. One of these was Joan Miró, the focus of a major retrospective at the Tate Modern this summer and the subject of five of Portabella’s shorter fiIms from the late 1960s and early 70s. (The two I’m most familiar with are Miró L’Altre, chronicling the artist’s painting and subsequent erasing of a mural at the Colegio de Arquitectos de Catalunya, and Miró 37/Aidez L’Espagne, which similarly explores a ‘making’ and ‘unmaking’, this time of Spain itself during the mid-1930s, via newsreel footage.)

Portabella’s relation to cinema has taken many different shapes. It started during the long reign of Francisco Franco, with Portabella producing Carlos Saura’s first feature in 1959, Los Golfos, swiftly followed by an early Marco Ferreri effort, El Cochecito. As one of the two Spanish producers of Viridiana (1961) — Luis Buñuel’s first Spanish feature, made towards the end of his extended career as a Mexican exile — he had the satisfaction of seeing the highly provocative feature win the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and then the frustration of having his passport confiscated as punishment for his involvement.

Meanwhile, Portabella was one of three credited co-writers on Francesco Rosi’s feature about bullfighting, The Moment of Truth (1965). He started making unclassifiable films of his own, often with surreal aspects, beginning in 1967 with the short Don’t Count on Your Fingers, followed a year later by a feature, Nocturno 29, whose ’29’ stood for the number of years Franco had by then held power. In keeping with that impertinent title, these films and those immediately following them, such as the even more radical Vampir Cuadecuc (1971), and Umbracle (1972), were originally shown in Spain only clandestinely. (The latter film included Catalan dialogue, a language then forbidden in the country.)

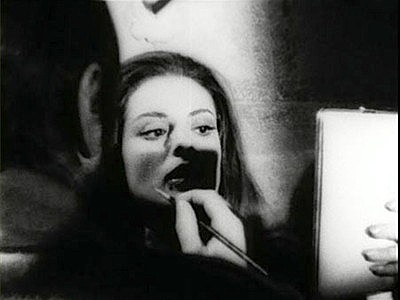

These were the first two Portabella films I saw and I’ve been a devoted fan ever since. Vampir Cuadecuc — still in some respects my favorite – sees Portabella very unconventionally filming in black and white the shooting of Jesús Franco’s very conventional color movie Count Dracula (1970), starring Christopher Lee. The material is submitted to a great deal of processing in visual textures and accompanied by a kind of musique concrète by Carles Santos, consisting of such elements as jet planes, drills, operatic arias, kitschy muzak and sinister electronic drones.

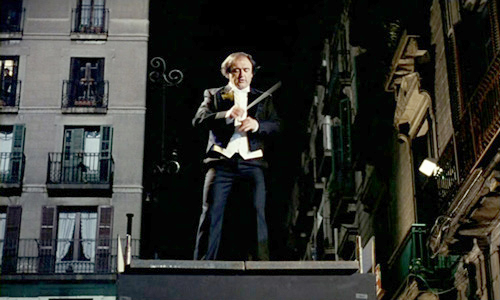

Often encompassing both the fictional vampire story and diverse non-fictional details involving props, actors and settings within the same camera movements, Vampir Cuadecuc maintains a kind of wit and lyricism that are carried over into the more varied materials of Umbracle, which might be regarded as Portabella’s own L’Age d’or (Buñuel’s 1930 film). These include a clown act, a statement about censorship, more Christopher Lee, found footage ranging from silent American slapstick to a 1948 Spanish propaganda feature, documentary tours of a shoe store and an assembly line of plucked chickens, and diverse narrative interludes subjected to aggressive editing.

Given Portabella’s tendency to elude most of the usual generic and commercial classifications, often while letting extended periods elapse between projects, it was hard to keep track of his work after that, at least until recently. (A long-awaited DVD box-set, including most or all of his films to date, is slated to surface soon.) Portabella’s most important films since 1972 have been Informe General (1976), a nearly three-hour political inventory of Spain filmed shortly after Franco’s death, and two ambitious features, Warsaw Bridge (1990) and The Silence Before Bach (2007). It’s important to add that (given the interval between Informe General and Warsaw Bridge) in 1977 Portabella was elected state senator in Spain’s first democratic election, which led to his participation in drafting the new Spanish constitution and assisting Spain’s entry into the European Common Market. (A complete account of his career and films can be found at his excellent website, pereportabella.com.)

Portabella’s profile as a political figure, as well as a filmmaker, has also entailed a widening array of interests in his last two features. Some of the major elements in Warsaw Bridge include: operas and concerts, a biology lecture, a novel, a swanky party, cooking, a forest fire and sex. All of these deftly interface into something resembling -– though never quite arriving at — a single narrative. And The Silence Before Bach, while featuring stunning performances of music by the composer, traverses several centuries and countries while exploring many interfacing topics.

The Pere Portabella season runs at London’s Tate Museum from 13 May to 31 July.