From Cineaste, Summer 2007. — J.R.

Walt Disney:

The Triumph of the American Imagination

by Neal Gabler. New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. 851 pp.,

illus. Hardcover: $35.00.

This is the first book by Neal Gabler since his magisterial and eye-opening An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (1988) that hasn’t seriously disappointed me, though I didn’t warm to its virtues right away. His 1994 biography of Walter Winchell (Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity) had less of an impact on me than the 1971 journeyman’s effort of Bob Thomas (which I also preferred to Michael Herr’s 1990 musings on the subject), while Life, The Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality (1998), which I barely remember now, felt at the time like all windup and no delivery. And one clear limitation of this hefty volume from the outset, in spite of its strengths, is that Gabler can’t function very effectively as either a critic of Disney’s films or as a historian of Hollywood animation; his talent lies elsewhere.

Given Gabler’s privileged access to Disney files and papers, this may be the closest thing to an authorized biography that we can expect to get, but it doesn’t exactly add up to an apologia — even though it refutes charges of Disney being anti-Semitic, and, apart from occasionally conceding that he was mainly a passionately anti-union Goldwater Republican, tends to depoliticize him. (Gabler seems eager to come up with a few nuggets to counter the usual profile, such as Disney’s reported remark to an employee about his studio around the time of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), “This whole place runs on a kind of Jesus Christ communism” —- “doubtless,” adds Gabler, “without realizing that he was the Christ” —- or Disney’s even more unexpected friendly correspondence with Paul Robeson in the early 40s about casting him as Uncle Remus in Song of the South.)

For better and for worse, this book is far more satisfying as a probe into the mysteries of Disney’s personality than as an examination of his art. But then again, practically every book about Disney ultimately falters on issues about art, regardless of who the author is, because the cultural issues tend to overpower the issues involving taste. And on matters of both taste and film, Gabler has less to offer on the subject of Disney than Leonard Maltin. Apart from deferring to Michael Barrier’s web site for a list of Gabler’s factual errors regarding animation, I would add that if Gabler were more of a film historian, he would have identified William de Mille as a director (and a significant one, with 53 films between 1914 and 1932) and not simply as a “writer and producer”. He also probably wouldn’t have recounted Disney’s extensive good-will tours of South America courtesy of Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney without noting that they’d previously sent Orson Welles on the same mission, and he might have recognized that Disney’s passing interest in casting Cary Grant and Cantinflas as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza was also —- and must have somehow been related to —- a project of Howard Hawks.

Still, given the massive amounts of factual material Gabler has to plow through, it’s perhaps understandable that he sometimes seems to be nodding at the switch. When he reports that Disney’s father-in-law “had become the government blacksmith,” he doesn’t pause long enough to explain what that job consisted of, and when he breezes past the U.S. publication of Felix Salten’s Bambi in 1928, he doesn’t mention —- and maybe doesn’t know —- that the translation from the German was carried out by Whittiker Chambers. Seemingly protecting himself against such distractions, he also manages to leapfrog past the startling yet parenthetical revelation that “Walt made it a point never to preview with children because he always insisted that his films were not made for children,” which I wish he’d elaborated on.

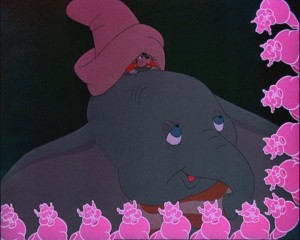

So it shouldn’t be too surprising that whenever Gabler broaches issues of artistic evaluation, he seems more interested in downgrading other positions than in defending his own. Typically, he suggests that Disney’s notorious remark about a sequence in Fantasia, “I think this thing will make Beethoven,” is a sign of his “alleged philistinism and sense of cultural imperialism” (my italics), without bothering to offer any alternative reading. And he seems strangely upset that Dumbo “received extravagant reviews, even though it had cost considerably less than its three feature predecessors and even though the animation was less painterly and realistic than on the previous features.”

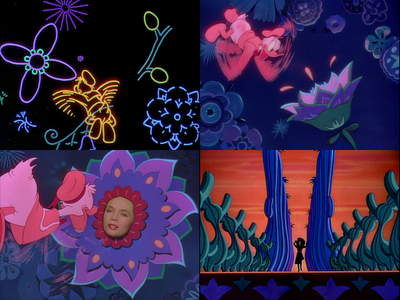

Gabler’s aesthetic orientation is already evident here, as it is in a sentence on the book’s jacket flap that accurately paraphrases his default position: “It was Disney, first with Mickey Mouse and then with his feature films —- most notably Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi —- who transformed animation from a novelty based on movement to an art form that presented an illusion of life.” In other words, speaking figuratively, goodbye Sergei Eisenstein, hello Jack Valenti. Even though the former gets three nods in the index while the latter gets none, it’s the middlebrow perspective of Valenti-speak that prevails —- the perspective of someone (i.e., Gabler) who could recently lament in the Los Angeles Times that “a Pauline Kael review in the New Yorker could once ignite an intellectual firestorm.” For my own taste, “a novelty based on movement” —- as exemplified by the Dance of the Pink Elephants in Dumbo, or the second half of The Three Caballeros —- comes closer to establishing Disney animation as an art form than any amount of lifelike illusion.

What I find valuable about this biography is its overall depiction of Disney as a frustrated artist — a facet that comes to the fore around the time of Fantasia (1940), his first sizable commercial flop — which proves to have almost as many ancillary implications as the portrait of Jews in flight from their ethnicity in An Empire of Their Own. One could of course make far too much out of the fact that Adolf Hitler was also a frustrated artist. But I still feel that Gabler offers a fresh insight into Disney’s character that explains all sorts of things —- even such posthumous Disney products as the recent Meet the Robinsons, which postulates a happy totalitarian city of the future conjured up by its young inventor-hero, called “Todayland” by its contemporary inhabitants, making it a kind of displaced artwork like Disneyland — a utopia conceived by and for soured individuals like Disney himself. Even in a dehumanized digital cartoon where all the characters look like flesh-colored vegetables, such a wistful vision all but replicates the melancholy, solipsistic highs of Disney’s career.

If indeed Disneyland qualifies as its namesake’s masterpiece — more than, say, Snow White (the Disney feature that appears to have more of his auteurist fingerprints than any other) —- this is supported by Gabler’s overall thesis: “It had always been about control, about crafting a better reality than the one outside the studio, and about demonstrating that one had the capacity to do so. That was what Walt Disney provided to America —- not escape, as so many analysts would surmise, but control and the vicarious empowerment that accompanied it.” Or, as he puts it later, “It was not the control of wonder that made Disneyland so overwhelming to its visitors; like so much else in Walt Disney’s career, it was the wonder of control.”

And interestingly enough, this often went beyond a desire to make money, especially in the early stages of Disney’s career. Even by the time of Snow White, “The tension between creativity and commerce, between doing the work well and making sure it was done profitably, was constant.” A hundred pages later, Gabler reports that “In just five years the [Disney] studio had swelled from three hundred employees to twelve hundred.” And then, 25 pages after that: “In effect, the studio was no longer Walt Disney’s fiefdom. He was now under the control of the businessmen.”

Thus, on the one hand, Disneyland could be described as a genuine labor of love that paid off spectacularly, exceeding “the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone Park, and Yosemite Park as a tourist attraction” less than two and a half years after it opened with its ten million visitors, and thereby confounding all the other amusement park operators, who were convinced it would fail. But the TV show that bore the same name, Disneyland, was strictly “a commercial,” designed to promote the theme park “and publicize the new [Disney] features.” (I’ve always harbored the conviction that certain aspects of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy empire and its capacity to turn part of its own operations into ads for other parts can be traced back to Disney in general and to his 1951 Alice in Wonderland in particular, multiple rabbit-head logos and all.) And once the labor of love and the commercials for it became difficult to distinguish from one another, Disney became as much a victim of the merger as anyone else, as if he’d been picking his own pocket.

The same childish sensibility that could wonder “How would a piano feel if Mickey bangs on it too hard?” (as Disney is reported asking at an early story session) or could insist “that Mickey and Minnie were married in real life, though they played boyfriend and girlfriend on screen,” could amuse himself, in his declining years prior to Disneyland, by building and operating a full-scale choo-choo train that circled his house. All of which suggests that Disney, as his own best customer — and contrary to Gabler’s forced and unnecessary opposition — ultimately regarded control as a form of escape, and vice versa. Put the two things together and the dollars keep pouring in, even if the boy inventor who started it all seemed to remain lonely and unhappy. Despite Gabler’s subtitle, it’s the sadness of the man and his personality that lingers in this book, conveying a perpetual sense of bereavement that curiously reminds me of doleful William Faulkner —- another frustrated artist in his own way, though a better one. -– Jonathan Rosenbaum