A post on the Chicago Reader‘s blog, Bleader. — J.R.

Adolescent sex in Oberhausen

I’ve just returned from the 53rd International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen, Germany, where I was invited to serve on the jury of FIPRESCI, the international film critics organization. My work, apart from participating in a panel about the privatization of film experience, consisted of seeing the 64 short films in the international competition and, along with two other jurors (Oliver Baumgarten from Cologne and Alexis Tioseco from Manila), awarding one of them a prize. We picked Amit Dutta’s 22-minute Kramasha from India — a dazzling, virtuoso piece of mise en scene in 35-millimeter, full of uncanny imagery about the way the narrator imagines the past of his village and his family.

The Festival had 14 prizes in all, gave a total of 30,000 Euros to many of the winning filmmakers, and concluded with a ceremony that lasted well over two and a half hours. Part of what made the event interesting was the same default position that sustained me through the 64 shorts I saw: the notion that at a festival as genuinely international as this one, a certain education was possible, however limited, in how people in other parts of the world were living and thinking — all of which provides a potential context for better understanding some of the choices involved, conscious or otherwise, in how Americans live and think.

Read more

The following essay was commissioned by Toronto filmmaker Ron Mann in 1992 for the book-spinoff of his documentary Grass. I wrote this around the same time that I reviewed Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai for the Chicago Reader, which helped to focus my conclusion; for more aspects of this argument, see “International Sampler”.—J.R.

What Dope Does to Movies

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

To the memory of Paul Schmidt

Consider how the camera cuts from Richie Havens’s face, guitar, and upper torso during his second number in Woodstock (1970) to a widening vista of thousands of clapping spectators, then to a much less populated view of the back of the bandstand, where there’s no clapping, watching, or listening — just a few figures milling about near the stage or on the hill behind it. What’s going on? This radical shift in orientation and perspective—a sudden movement from total concentration to Zenlike disassociation — is immediately recognizable as part of being stoned, and Michael Wadleigh’s epic concert film, which significantly has about the same duration as a marijuana high, is one of the first studio releases to incorporate this experience into its style and vision.

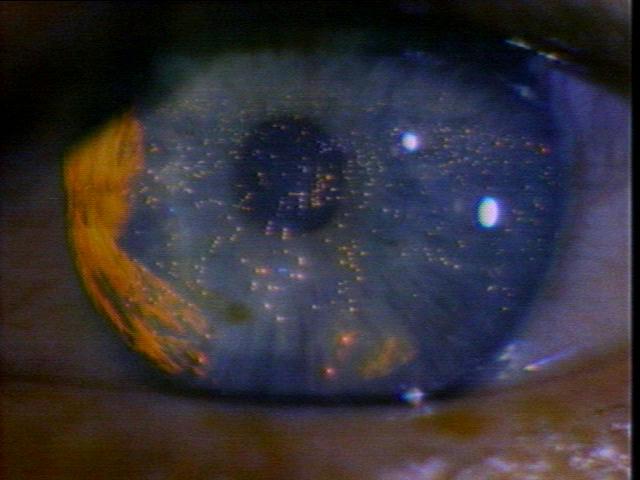

Or think of the way that Blade Runner (1982) starts: a long, lingering aerial view of Los Angeles in the year 2019, , punctuated by dragon-like spurts of noxious yellow flames, with enormous close-ups of a blue eye whose iris reflects those sinister, muffled explosions. Read more

Written for the Jeonju International Film Festival in March 2009. I can happily report that, according to Portabella, his DVD box set containing all or most of his films to date will finally be released later this year. — J.R.

My first problem in coming to terms with No Compteu Amb Els Dits (1967, 26 minutes), Pere Portabella’s first film, is my inability to distinguish between every one of what he himself identifies as its 28 separate fragments, each one reportedly lasting between 15 seconds and two minutes. Counting the segments myself — not with my fingers, but with a pen, a piece of paper, and a VCR — I come up with only 24, not 28 But then again, the only obvious ways of distinguishing one sequence from another are (a) changes in themes, characters, and/or settings, (b) changes in the music, (c) other changes in the soundtrack involving sound effects, dialogue, or narration, (d) switches between black and white and color (or vice versa), and (e) graphic transitions that are apparently similar to those used in Spanish commercials shown in cinemas during this period. And at one point or another, Portabella seems to defy most of these conventions by eliminating or obfuscating such markers. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1988). — J.R.

Originally entitled The Story of Asya Klachina, Who Loved a Man but Did Not Marry Him Because She Was Proud, Andrei Konchalovsky’s remarkable 1967 depiction of life on a collective farm, one of his best films, was shelved by Soviet authorities for 20 years, apparently because its crippled heroine is pregnant but unengaged and because the overall depiction of Soviet rural life is decidedly less than glamorous. (The farm chairman, for instance, played by an actual farm chairman, is a hunchback.) Working with beautiful black-and-white photography and a cast consisting mainly of local nonprofessionals (apart from the wonderful Iya Savina as Asya and a couple others), Konchalovsky offers one of the richest and most realistic portrayals of the Russian peasantry ever filmed, working in an unpretentious style that occasionally suggests a Soviet rural counterpart to the early John Cassavetes. Many of the men in the cast relate anecdotes about war and postwar experiences that are gripping and authentic, the interworkings of the community are lovingly detailed, and the handling of the heroine and her boyfriends is refreshingly candid without ever being didactic or sensationalist. Episodic in structure and leisurely paced, the film is never less than compelling. Read more

Published in Sight and Sound, January/February 2019. Alas, this list was put together before I saw A Bread Factory, playing in Chicago at the Gene Siskel Film Center this coming weekend. I’ll be introducing the Saturday screening at 2 pm and interviewing Patrick Wang afterwards. — J.R.

In alphabetical order:

Cold War (Pawel Pawlikowski)

Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun? (Travis Wilkerson)

The Other Side of the Wind (Orson Welles)

Ray Meets Helen (Alan Rudolph)

Roma (Alfonso Cuarón)

If ties are permitted, I would add The Image Book(best experimental film, Jean-Luc Godard) and First Reformed (best love story, Paul Schrader).

Read more

Read more

Just posted on the website Con Los Ojos Abiertos (which literally means With the Eyes Open), Christmas 2018. (https://www.conlosojosabiertos.com/la-internacional-cinefila-2018-las-mejores-peliculas-del-ano/)

If I’d sent this in a bit later, I would have somehow managed to include A Bread Factory (Patrick Wang). — J.R.

Best Films:

The Other Side of the Wind (Orson Welles)

The Image Book/Le Livre d’image (Jean-Luc Godard)

Do You Wonder Who Fired the Gun? (Travis Wilkerson)

Roma (Alfonso Cuarón)

The eye was in the tomb and stared at Daney/L’oeil était dans la tombe et regardait Daney (Chloé Galibert-Laîné)

To varying degrees and in different ways, all 0f

of these films or videos are experimental,

which is also true of the two films found below.

Best debut feature: The Chaotic Life of

Nada Kadić (Marta Hernaiz Pidal, Mexico)

Best commercial film from the U.S.: A Simple

Favor (Paul Feig)

Read more

Read more

From the Spring 1972 issue of Film Comment; this is also reprinted, with a lot of contextual material, in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles (where I’ve also retained my original title — not used by Film Comment, who ran it as an untitled review). I’m still hugely embarrassed by the assertion early in this piece that “[Kael’s] basic contention, that the script of KANE is almost solely the work of Herman J. Mankiewicz, seems well-supported and convincing” — a howler if there ever was one. I’m not sure if this would qualify as a valid excuse, but this was the first lengthy essay about film that I ever published. My joint audio commentary with Jim Naremore on Criterion’s new KANE box set addresses some of Kael’s more dubious factual and critical assumptions.

Recently I‘ve been reading Brian Kellow’s biography of Pauline Kael, and I’m very pleased that he’s up front about the serious flaws of “Raising KANE,” factual and otherwise — but also disappointed that Kellow is unaware that “The Kane Mutiny” — signed by Peter Bogdanovich, and the best riposte to Kael’s essay ever published by anyone — was mainly written by Welles himself. (See This is Orson Welles and Discovering Orson Welles for more about this extraordinary act of impersonation.) Read more

Written for a booklet distributed at the 2018 Venice International Film Festival. — J.R.

Most people reading these words have likely heard about the Iranian New Wave, which conjures up such names as Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf, and Panahi. But until recently, Westerners who have heard about the first Iranian New Wave, whose names include Farrokhzad, Golestan, Kimiavi, and Saless, have been few and far between. Apart from the belated availability in the West of Forough Farrokhzad’s 1962 short film The House is Black, this watershed prerevolution movement in Iranian cinema has almost been lost to history due to the abrupt European exiles of many of its other major artists — Ebrahim Golestan to England, Parviz Kimiavi to France, and Sohrab Shahid Saless to Germany. (Bahram Beizai, Dariush Mehrjui, and Amir Naderi are among the few filmmakers who might be stylistically associated with both waves, but given how seldom their own prerevolution films are seen nowadays, apart from Mehrjui’s The Cow, it’s difficult to say much about them.) Arguably even more innovative as well as more modernist than the second New Wave, and virtually contemporaneous with the French New Wave, Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (1962), Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (1963-64), Kimiavi’s The Mongols (1973), and Saless’ A Simple Event (1974) are masterworks that continue to speak to the present like few other films. Read more

Written for the Savannah-based, online Cine-Files in May 2014, posted circa early June, and reprinted here, with their permission (and some added illustrations). — J.R.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: For me, a key part of your argument in Acting in the Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988) occurs in your fourth chapter, “Expressive Coherence and Performance within Performance,” when you argue that even a sincere expression of one’s feelings is an actorly performance, “because the expression of ‘true’ feeling is itself a socially conditioned behavior.” Which then leads you to quote from Brecht:

“One easily forgets that human education proceeds along theatrical lines. In a quite theatrical manner a child is taught how to behave; logical arguments only come later. When such-and-such occurs, it is told (or sees), one must laugh….In the same way it joins in shedding tears, not only weeping because the grow-ups do so but also feeling genuine sorrow. This can be seen at funerals, whose meaning escapes children entirely. These are theatrical events which form the character. The human being copies gesture, miming, tones of voice. And weeping arises from sorrow, but sorrow also arises from weeping.” (69)

It seems to me that one reason why acting tends to be neglected in film criticism is that we can too easily confuse it with other elements — writing, directing, the ‘auras” of certain personalities, even certain casting decisions — in much the same way that we’re often confused or misguided about the sources of our own behavior (such as, are we weeping to express sorrow or to produce sorrow?) Read more

From Film Comment (January-February 1973). — J.R.

JEAN RENOIR: THE WORLD OF HIS FILMS by Leo Braudy. Doubleday & Co., New York, 1972; hardcover $8.95; 286 pages; illustrations, index.

I’ve often wondered why a disproportionate amount of bad film criticism comes from English teachers. One would suppose that anyone devoted to narrative, lyric and dramatic structures would have some sensitivity for and interest in movies, but look at the recent issues of literary magazines like Modern Occasions, Partisan Review and The New York Review of Books and see what they usually have to offer in their “movie chronicles”: bilious, solipsistic professors who waste their time at EASY RIDER and THE GRADUATE (or DEATH IN VENICE and THE GO-BETWEEN) and then conclude that film is a “low art” or an overrated medium because these works don’t live up to the claims of their publicists. Even a critic like Stanley Kauffmann — who should know better — will complain (in a recent Film Comment) that “a list of memorable foreign films” for 1970 would only run to three or four titles, implicitly making the assumption that he’s seen all the likely candidates: a standard literary procedure, at least in America.

Fortunately, Leo Braudy, an English teacher, shares none of the false snobbery and little of the myopia about film that tends to plague his profession. Read more

From Film Comment, September-October 1984. — J.R.

Rear Window, The Leopard Man [see first two photos above], Phantom Lady, The Window, The Bride Wore Black, Mississippi Mermaid. Considering that almost 30 features have been Cornell Woolrich adaptations, it seems a genuine anomaly that he should remain so shadowy a figure. He is as central to the thriller as Olaf Stapledon is to science fiction, and has been comparably eclipsed by a singularity that exceeds and surpasses some genre expectations while grievously falling short of certain others. Despite all the purple prose, tired rewrites, and preposterous plots that crop up in his fiction, perhaps no other writer handles suspense better, or gives it the same degree of obsessional intensity. More soft-boiled than hard-boiled in the depiction of his heroes and heroines, Woolrich nonetheless seems central to the overall pessimism of film noir in the violent contrasts of his moods and the dark tempers of his villains.

Webster’s New Collegiate gives three definitions of dreadful: “(1) (adjective) inspiring fear or awe, (2) (adjective) distressing, shocking; very distasteful, (3) (noun) a morbidly sensational story or periodical; as, a penny dreadful.” Woolrich assumes all these meanings and invents a few more of his own. Read more

Although I couldn’t bring myself to watch all of Trump’s rally speech in Tulsa last night, I did tune into the Fox channel enough times to catch the gist of most of it. I wanted to solve the mystery about what was attractive enough to the 6200 or so mostly unmasked individuals to risk their lives and those of their friends and families in order to see and hear him rant and strut and thank everybody in person. And I think I came away with a provisional answer. (For those who missed all of it, or even some of it, I’m pasting the transcript of his endless dribble below in bold, all 28 pages of it.)

As usual, his spiel was all about grievance. The fact that he seemed to spend an eternity complaining about the media treatment of his walk down a ramp after his West Point graduation speech and his use of two hands while sipping water during the speech — what seemed like at least 15 minutes (or about four of the 28 pages) seeking to justify his behavior over just a few seconds — only proved that his inferiority complex was still the most discernible aspect of his ego, and clearly an aspect that many or most of his 6200 or so fans shared. Read more

An essay written for Toronto’s Cinematheque Ontario program guide (February 2007). –- J.R.

For better and for worse, and principally the latter, Jacques Rivette has been singled out as the former Cahiers du Cinema film critic who makes the least commercial films, as well as the longest ones. But for the record, the films of the always-neglected Luc Moullet [screened in Cinematheque Ontario’s Spring 2006 season –- ed.] are generally less commercial than those of Rivette. And even what we mean when we say “longest films” is open to some debate. (After all, the over twelve-hour OUT 1: NOLI ME TANGERE was conceived as a TV serial, and Jean-Luc Godard’s own first TV series, made a few years later, was just as long.)

The problem with such caricatures is they generally function as excuses for why some spectators won’t deal with Rivette’s films rather than as viable descriptions of what they offer. Yes, his features tend to be long and they work with duration. Furthermore, when two versions have been made of some of them –- unauthorized in the case of L’AMOUR FOU, authorized in the cases of L’AMOUR PAR TERRE and LA BELLE NOISEUSE/ DIVERTIMENTO – the longer version is almost always superior. Read more

My column for the March 2020 issue of Caimán Cuadernoas de Cine… — J.R.

Greasing the wheels of commerce is usually the chief reason for end-of-the-year movie polls, which, like the Academy Awards, only intensifies our ongoing cultural confusion of film criticism with advertising. This helps to explain why (and how) Harvey Weinstein became Janet Maslin’s favourite film critic in her 1999 Cannes coverage for the New York Times, devoting far more space to his (negative) opinions about the prizes than anyone else’s, including the jury’s. (The fact that his own films in the festival hadn’t won prizes was of course crucial.) Perhaps because the head of that jury was David Cronenberg, an intellectual, the need for anti-intellectual cultural arbiters to drown out such controversial choices was as pressing two decades ago as it is today. We all need to be told not once, but repeatedly, why Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is more important to the state of our civilization, our lives, our senses, and even our ethics than Vitalina Varela, and whereas this sort of gatekeeping function was once reserved for the Times and its consumerist equivalents, today its counterparts have included, among others, Sight and Sound, Film Comment, the New York Review of Books, the London Review of Books, Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, and, alas, even Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 9, 1987). 2018: Criterion has a delightful digital edition of this.– J.R.

The nice thing about Rob Reiner’s friendly fairy tale adventure, with a script by William Goldman adapting his own novel, is how delicately it works in irony about its brand of make-believe without ever undermining the effectiveness of the fantasy. The framing device is a grandfather (Peter Falk) reading a favorite book aloud to his skeptical grandson (Fred Savage), and it’s the latter’s initial recalcitrance that the movie uses both as a challenge and as a safety net. In the imaginary kingdom of Florin, the beautiful Buttercup (Robin Wright) gets separated from the farmhand whom she loves (Cary Elwes) and betrothed to the evil Prince Humperdinck (Chris Sarandon), until the nefarious Vizzini (Wallace Shawn) sprints her away. The colorful characters and adventures that ensue are, at their best, like live-action equivalents to some of the Disney animated features, with lots of other fond Hollywood memories thrown in: Andre the Giant is like a cross between Andy Devine and Lumpjaw the Bear, while Mandy Patinkin’s engaging Inigo Montoya conjures up Gene Kelly in The Pirate. Every character, in fact, is something of a goofball, and while the film is inexplicably saddled with a PG rating, it delightfully cuts across age barriers to keep everyone charmed. Read more