From Tikkun, November/December 1990, Vol. 5, No. 6. This was my second and (to date) final contribution to this magazine. As I recall, I wasn’t too happy with the way I was edited on this one (although the published version — which they called “Out to Lynch,” and is only slightly altered here — is the only one I have now); I was much happier working with Peter Cole on my previous article for Tikkun, “Notes Towards the Devaluation of Woody Allen“. -– J.R.

“All I know for sure is there’s already more’n a few bad ideas runnin’ around loose out there.” — Sailor to Lula in Barry Gifford’s Wild at Heart: The Story of Sailor and Lula

I couldn’t care less about changing the conventions of mainstream television. — David Lynch, November 1989

From The Birth of a Nation to Fatal Attraction, puritanism and political naïveté have frequently turned out be a winning combination in American movies. The recent popularity of David Lynch, however, puts a new spin on this formula. Sailor’s line — repeated in Lynch’s new movie based on Gifford’s novel — in a way summarizes Lynch’s work to date: an oeuvre that has recently expanded from paintings, movies, and a weekly comic strip to include two new TV series (Twin Peaks and American Chronicles, both coproduced by Mark Frost), an opera, a pop record album, commercials for Calvin Klein, a coffee-table book due out next fall, and undoubtedly other enterprises as well. Like his puritanical predecessors Walt Disney and Hugh Hefner, with their endless capacity for generating mutually promoting spinoffs, Lynch seems well on his way to becoming one of those multinational entertainment conglomerates that are currently clogging the cultural scene. What seems to set him apart most strikingly from other puritanical political naifs, multinational and otherwise — individuals obsessed with “dirty secrets,” who regard “dirt” as a matter of sexual propriety rather than sexual ethics — is that he is perceived and celebrated in some quarters not as an integral part of this country’s present ideological mainstream but as a serious artist subverting the American soul from within.

There’s certainly no question that Lynch is an original talent, and that Twin Peaks, whatever its built-in limitations regarding format and overall coherence, represents something both fresh and slightly transgressive in prime-time TV. It also can be argued that a progressive coarsening in Lynch’s work since the1970s has corresponded fairly closely to a rise in his popularity and overall critical reputation. (This coarsening was exacerbated by his parting of ways with Alan Splet, the brilliant sound designer who worked on all his films up through Blue Velvet, whose subtle and delicate grasp of aural textures added much density and complexity to Lynch’s conception.) Significantly, when the New York Times belatedly reviewed his first and most accomplished feature, Eraserhead (1976), two years after the film’s release, its reviewer found it ” murkily pretentious,” ” interminable,” and ““sophomoric,” with no redeeming virtues at all; roughly a decade later, a Lynch cover story in the Sunday Times Magazine called the same movie “an astonishing feature debut.” Even the most cursory comparison of Eraserhead with Wild at Heart reveals an artistic decline so precipitous that it is hard to imagine the same person making both films; but it is the latter movie that won the Cannes Film Festival’s Golden Palm.

It’s clearly too early to reach any final conclusions about Lynch’s work, but not too early to consider the particular allure and cachet that it currently has. Sailor’s line can be said to summarize Lynch’s works, not only because they contain more than a few “bad ideas” running around loose, but also because that is paradoxically their most seductive aspect. It’s a statement based on disavowal: “out there” rather than “in here” is the operative phrase, the open sesame that makes everything else possible. Disavowing any responsibility for bad ideas becomes the prerequisite for Lynch’s having and entertaining them and for the audience’s sharing them. As long as they’re “out there,” running around loose and free, they can be enjoyed voyeuristically as a purely external spectacle, without any conscious capitulation to ideological meaning. A notion of internalized holiness and propriety combined with externalized evil and degradation adds up to a form of unquestioning xenophobia that fetishizes “the other” without wishing to understand it, much less cope with it.

Strategic absences in works of art often function like mirrors, reflecting the desire of the audience, and the absence of any social analysis in Lynch effectively becomes a form of invitation. Leftists who want to see the ugliness and depravity of middle America laid bare in Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, and Wild at Heart are amply rewarded. What they fail to realize is that some middle Americans are titillated and delighted by the same guiltless Lynchian spectacle. These Americans don’t see their own image, but another vision produced by the xenophobia and paranoia that liberals see when looking at them: white trash, perverts, criminals, lunatics -– a lot of “bad ideas” running around loose out there, waiting to be both savored and ridiculed.

There no doubt that a certain amount of subversion of film form exists in Lynch’s work, at least if one places it alongside the mainstream models it deliberately evokes. Peyton Place in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks, The Wizard of Oz and Elvis Presley movies in Wild at Heart. (On the other hand, the attempt by some critics to link this formal subversion with Luis Buñuel’s surrealism is a different matter entirely; indeed, it can only be done by disregarding Buñuel’s radical politics.) Part of this simply stems from the fact that Lynch, who is fundamentally a painter in orientation, uses the narrative come-ons of his mainstream models without having their strengths in storytelling — the ” dirty” small-town secrets depicted by Peyton Place, the magical adventures on the road promised by The Wizard of Oz, and the anticipation of violence and rebellion elicited by Elvis movies — and without worrying too much about motivations, loose ends, or solutions to the other mysteries posed by his characters and plots. It might be added, moreover, that camp and postmodernism had altered his narrative models long before Lynch ever got to them, by cutting them loose from their original contexts and setting them adrift as part of a stock repertory of pop icons.

***

But Lynch’s conscious uses of camp — -which, even more than his surrealist imagination, seem the key to his recent success — are a different matter entirely. It’s debatable whether any of the kitschier conceits of Blue Velvet — such as the double-edged notion of robins as harbingers of love and/or as nasty predators — qualify as conscious camp. It seems much likelier that Lynch was dead serious about motifs like the robin but, after discovering that his fans hooted appreciatively at the naïveté such notions, realized that they constituted a bankable asset, and started employing them more deliberately in Twin Peaks, and then more extensively in Wild at Heart. In the latter, Oz and Elvis are evoked periodically, not to enhance or comment upon the two leads, Lula (Laura Dern) and Sailor (Nicolas Cage), but literally to supplant them whenever Lynch’s invention and involvement flags.

Lynch’s camp entails another disavowal: it simultaneously offers an “homage” to a cherished icon and ridicules that icon. It proclaims that the icon still has affective power and that it no longer has or deserves its original affective power. The same adolescent mixture of worship and derision, piety and irreverence can be found in its most distilled form in many rock videos, and it might be argued that it resembles in some ways the jaundiced attitudes of many younger Americans about contemporary politics. (Reagan and Bush may be jokes, but they are jokes that one votes for, or at least tacitly supports.) It grants to every position and attitude a built-in escape clause: accuse it of being cynical and corrupt, and it flaunts its innocence; accuse it of being innocent and naïve, and it smirks or jeers.

On the surface, there appears to be no one around at the moment in American movies who is more “wicked” and transgressive than Lynch. But consider how much his work’s apparent refusal of politics fits right in with the etiquette of the contemporary pop mainstream. (By contrast, Alan Moyle’s formally unadventurous but bracingly collectivist, activist, and uncynical Pump up the Volume [see above], which seems to be dividing audiences as much as Wild at Heart, is the real taboo-breaker–so much so, in fact, that even many mainstream reviewers who have been supporting the film have been going to great lengths to avoid and conceal its political thrust.) Yet placed within a puritanical rather than a political context, the sheer irresponsibility of Lynch’s vision gives an undeniable lift to some viewers. There’s something thrilling about the wild amorality of a dark, surrealist imagination producing little shocks by unleashing its bad ideas inside“wholesome” dream images of middle America. And according to certain liberal arguments that are being made on behalf of these kicks, there’s something intrinsically liberating, perhaps even progressive — and at the very least kinky – about these rude challenges to mainstream complacency. But the leap that’s implicitly being made between “liberating” and “kinky” on the one hand and “progressive” or “subversive” on the other is a leap that can only be taken with one’s eyes closed — the way, alas, that many people prefer it.

A little further down the same page in Gifford’s novel where Sailor expounds upon “bad ideas,” he has something else to say that is not included in Lynch’s movie: “My experience, the more people get to know each other, the less they get along….It’s best to keep people to bein’ strangers. That way they don’t get disappointed.” The social defeatism expressed in these words lies at the heart of the Lynchian world, although the surface expositions of The Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, and Wild at Heart (the movie), with their campy or at best half-hearted displays of piety, hope, love, and innocence, periodically seek to deny it.

Gifford sees the social meaning implicit in Sailor’s first statement and labels it as such by adding Sailor’s defeatist coda. Lynch leaves this second statement out because it might interfere with the movie’s apparent freedom from ideological meaning – a notion of aesthetic bliss that might be called the Lynch-pin fallacy. And some liberals who are drawn to this apparent aesthetic freedom, but who feel obliged for puritanical reasons to grant a higher purpose to their pleasure, wind up calling it subversive.

Lynch’s work should be contested, if at all, not for puritanical reasons but political ones. Yet puritanism is buried so deeply within American political thought, infusing so many attitudes on the Left as well as the Right, that this is easier said than done. As George Orwell noted in the course of recording his distaste for Salvador Dali, “Obscenity is a very difficult question to discuss honestly. People are too frightened either of seeming to be shocked or of seeming not to be shocked, to be able to define the relationship between art and morals.” And this difficulty becomes compounded when people partially praise shocking work not because of its effect on themselves but because of its projected or imagined effect on others, a process which enables liberals to think that this film will have a progressive effect on middle America. Moreover, Lynch’s puritanism, like Hugh Hefner’s, is difficult to attack unpuritanically because its defiance of certain taboos means that criticizing it can seem to be an assault on freedom of expression. Theoretically, one can support that freedom while criticizing the uses that are made of it. But in practice, at a time when widespread impatience with the Bill of Rights is already jeopardizing free expression, it is often difficult to make such fine distinctions without being misunderstoood.

***

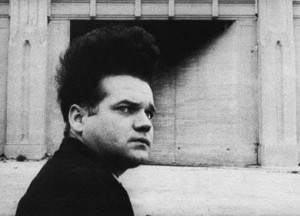

One hears that there are plans afoot to rerelease Eraserhead sometime next year. This black and white film — painstakingly crafted as a low budget independent venture over five years of patient effort — has been available on video for a few years, and prior to that had an extended life as a midnight movie staple, but many of Lynch’s recent fans still haven’t seen it. Conceivably the most original first feature by an American filmmaker to have appeared during the seventies, and certainly one of the most remarkable, it is inevitably handicapped commercially by its lack of any secure genre affiliation. Nor does its difficult story line offer any camp or postmodernist escape clauses. While its grim fatalism and its biological determinism (a sense of “dirty secrets” that is more cosmological and philosophical than social) make it every bit as conservative in its implicit social philosophy as the studio productions by Lynch which follow it– a subject that J. Hoberman and I have already explored at some length in our book Midnight Movies — its meditative style is such a radical departure from Hollyvood narrative norms that it can’t be accused of pandering to anyone.

Ignored by most critics of experimental films, art films, and exploitation films –despite (or maybe because of) the fact that it has certain traits in common with all three categories — and treated dismissively by most mainstream reviewers at the time, Eraserhead found its limited audience only through the patience and dedication of its distributor, who kept the movie playing as a midnight attraction for many weeks long before it developed anything resembling a cult. Today, given both the demise of most midnight movie venues and the pressures on commercial pictures to perform at the box office immediately, a film as singular as this one without any obvious marketing handle (such as Lynch’s name) would hare almost no chances for success at all.

Lacking any conventional sense of plot or character, Eraserhead revolves around a dreamy and sappy young man named Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) living with an undernourished, twig-like plant in a dark, squalid furnished room in an urban industrial wasteland. Invited to a grotesque family dinner by his former girlfriend Mary, he discovers that he’s fathered an illegitimate monster that resembles a wormlike fetus; Mary and their yowling, premature offspring move into Henry’s room. The creature becomes sick and its persistent cries eventually cause Mary to flee in the middle of a rainy night. Henry unsuccessfully tries to nurse it back to health, and when he fails, eventually destroys his progeny and, by implication, himself and the entire universe in the process.

A bleak tale, to be sure, but most of the movie unfolds less like a story than like a sardonic metaphysical meditation on the contents of Henry’s mind: a landscape of fantasy textures, mysterious processes, and industrial noises held together by dovetailing obsessions about sex, machinery, biology, botany, astronomy, and theology, all of them expressed nonverbally. And insofar as the movie has a story, it is nearer to nightmarish absurdist comedy than to angst-ridden tragedy. The closest European art-movie equivalents are not Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni, but Orson Welles’s The Trial, the black and white sequences in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker or (for its musically timed and comically abstract uses of silence and sound) Jacques Tati’s Mr. Hulot’s Holiday. Informed by a mesmerizing formal beauty and a highly distinctive form of black humor, with meditative rhythms that turn its slender plot into a perpetual series of discoveries and revelations, Eraserhead is a sui generis masterpiece that most spectators and critics never quite know how to take.

***

The same thing can’t be said for any of Lynch’s subsequent movies, whether he’s worked as a hired hand (The Elephant Man and Dune), generated his own material (Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks), or adapted someone else’s material for his own purposes (Wild at Heart). It could be argued, moreover, that Lynch’s increasing visibility and popularity is largely a function of the fresh contexts in which his work has appeared. Compared to Eraserhead, Blue Velvet is like TV soap opera, and compared to Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks seems formally unadventurous and fairly tame in terms of subject matter; but compared with other TV serials, Twin Peaks looks like a bolt from the blue.

Still, we live in a culture where it’s important for watered-down work to reach a mass audience: twenty million households watched Lynch’s initial two-hour Twin Peaks when it first aired. In Twin Peaks, this watering down entails, among other things, obligatory (if lame) narrative justifications for most of the bizarre visual and rhythmic patterning. If a fluorescent light sputters over a corpse in a morgue, there’s a line of dialogue that tells us this is due to a faulty transformer; if a gigantic elk’s head inexplicably covers the table in a small room, we’re eventually told that it fell down from the wall.

Reportedly, a wild Eraserhead-like dream sequence in the third episode (also directed by Lynch) — involving a dancing dwarf and dialogue recorded backwards — was used as a twenty-years-later epilogue to the pilot when the latter was released on video in Europe. This sense of arbitrarily placed parts is even more pronounced in the various lunatic cameos and walk-ons that punctuate the narrative of Wild at Heart: how much would be lost or gained if Jack Nance and his demented speech about dogs turned up in New Orleans instead of Big Tuna? It might be said that many of the eccentric minor characters in Eraserhead are indistinguishable from the film’s mood and atmosphere and that those in Blue Velvet are used to establish mood and atmosphere. But in Wild at Heart they’re like guest-star appearances in an ongoing surrealist vaudeville. It’s close to the camp tactics of John Waters at his most linear and primitive, who simply piles on the shocks at random to pull back an audience’s drifting attention. For a mainstream audience whose pleasure at the movies appears to be becoming increasingly dependent on the quantity and degree of such shocks, Lynch’s scattershot cornucopia of lurid bits can be interpreted as a simple business move: giving the audience what it seems to want.

***

Lynch has never shown even the slightest interest in social realism. He blurs the line between the fifties and the present in all his films since Blue Velvet and makes a botch of all the Southern accents and class distinctions in his adaptation of Gifford’s novel; but one can reasonably argue that his only true subjects are inner landscapes. Yet insofar as inner landscapes are.at least partially dependent on external realities, one should note that Lynch’s moral universe is made up of mutually exclusive categories: holy fools and scumbags, Madonnas and whores. The shared empty-headed bliss of Lula and an elderly black man in overalls at a filling station nodding to an old-fashioned big band tune, is a kind of communion founded on innocence. Similarly, the sleazy side of Lula (who is half Madonna, half whore)achieves another kind of communion with scumbag Bobby Peru (Willem Dafoe) when she finds herself succumbing to his crude advances.

The ideological consequences of these divisions are fully apparent in the opening scene. While Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood ” plays, Sailor and Lula are accosted by a black man named Bob Ray Lemon, who leers at Lula and refers to her as a “cunt,’ baits Sailor, adds some cumbersome and naturalistically implausible exposition about why he is doing this, and draws a knife. Sailor very promptly and graphically bashes the man’s brains out on a banister and the marble floor, then melodramatically lights a cigarette and makes an Elvis-like gesture: he points accusingly at Lula’s mother (Diane Ladd), who instigated the incident.

The fact that Sailor kills someone named Bob Ray Lemon is alluded to in the novel, but the circumstances and details are omitted; given both the name and the Southern setting, it seems perfectly reasonable to assume that Gifford’s Bob Ray Lemon is white. Why, then, does Lynch make him black? Presumably, because a black man leering at a Madonna-like Lula and then getting brutally murdered by the hero adds drama and, for some spectators, additional pleasure to the scene. And why does Lynch end the scene with two separate camp gestures that succeed in drawing laughs? Presumably, to release any guilty tension set up by the preceding drama and pleasure. The separate escape clauses disavowing both seriousness and social content work hand in glove, or better yet, hand over fist; pandering to racism becomes aesthetic boldness, an appeal to “pure” sensation, and –- if one subscribes tothe unlikely hypothesis that a political innocent like Lynch is hoping to outrage liberal sensibilities –- a form of subversion.

“In dreams begin responsibilities,” Yeats wrote, but not, it would seem, in the dreams that Lynch asks us to share. In a puritanical culture heavy with guilt and fear there is something irresistible about the danger and bravado of taboo-breaking that is unbounded by conscience or analysis — a roller-coaster ride into the notions of depravity that a repressed adolescent might have. Seen without irony, Blue Velvet resembles the lurid, confused imaginings of a sheltered twelve-year-old boy wondering what sex between his parents might be like; seen with irony, it can be taken as something more grown-up — the cynical scoffing of an adult about his own childish notions. By concentrating rigorously on his childish notions of biology, Lynch’s formalism in Eraserhead can be said to analyze the ideological superstructure of the hero’s adolescent viewpoint. But when he exercises more shock-ridden aesthetic tactics on what purports to be a real world in Wild at Heart, he’s playing into the hands of our worst racist fantasies.

Perhaps the most painterly thing about Lynch is his interest in iconic figures rather than characters. Indeed, the closest things to fleshed-out characters in his work –Henry (Jack Nance) in Eraserhead, the amateur detective (Kyle MacLachlan) in Blue Velvet, and the FBI agent (MacLachlan again) in Twin Peaks — also happen to be the three clearest self-portraits, all of them satirical and comical but just as clearly appreciative and affectionate. The evolution from hapless, unemployed Henry to faltering college boy Jeffrey Beaumont taking a walk on the wild side, to superhero federal agent Cooper, an all-American genius and mystic sleuth, offers plenty of food for thought about where Lynch thinks he’s heading. To claim that he’s ideologically innocent and naïve about his xenophobic fantasies seems reasonable enough; so are many of us, much of the time. But to claim that he’s ideologically neutral — or even worse, progressive — is to succumb to that same innocence and naïveté.