Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. — J.R.

June 7, 1994

Dear Jonathan,

Sorry to have been so long replying. As you say, much has happened since you wrote your letter. We both started out years ago in a series of polemical articles to correct received ideas of Welles, and we seem to be making progress. This Is Orson Welles and It’s All True will be more widely read and seen than those articles ever were. Already Richard Combs, writing about f for fake in the January–February 1994 Film Comment, acknowledges the thesis of Welles the independent filmmaker advanced by you in “The Invisible Orson Welles” as a corrective to the idea of Welles the great failure, then proceeds to propose a new theory of the work, with failure of another kind inscribed in it from the start. That article would have been unthinkable a few years ago, when what might be called the vulgar theory of failure was still dominant.

The work on the Welles legacy is going well: Oja is set to co-direct a documentary that will include several of the important fragments; The Deep and The Other Side of the Wind may be finished in the next couple of years, and hope springs eternal where The Merchant of Venice is concerned. I don’t rule out the possibility that someday we’ll see Don Quixote finished properly, when all the pieces of the negative are finally assembled in one place and scholarship and craft replace the rush to release that resulted in the embarrassing version that was shown at Cannes in 1992. And, hopefully the “restored” Chimes at Midnight won’t repeat the mistakes of the “restored” Othello — in large part because of the campaign for fidelity to Welles that you started in the pages of the Chicago Reader and Todd McCarthy carried on in Variety.

I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but we seem to be in an era of salvagers. As the future of cinema looks dimmer, the makers of laserdiscs are scrambling to rescue “directors’ cuts” of mutilated films and other lost work from the past to recycle them into our home viewing spaces. Some of this is bogus, motivated by capitalism’s “new and improved,” or worse: by the video equivalent of the wave of technomania that swept the country when stereo record players were the new fad, and the words “woofer” and “tweeter” were on every hobbyist’s lips. On a recent visit to a big video store in L.A. with Marco Müller, I suddenly felt sad at seeing everything from Cliffhanger in letterbox format to the director’s cut of The Fearless Vampire Killers, neatly ranged on shelves in packages where they will be joined shortly by It’s All True and inevitably by the other Welles “phantoms.” The museums are replacing theatres. The Centenary looms.

Which is not to say that It’s All True didn’t need to be finished. So does The Big Red One, which promises to be a masterpiece if Sam Fuller is ever allowed to do his four-hour cut. I’m quite sure Susan Ray will find a way to finish We Can’t Go Home Again, which has so many affinities with The Other Side of the Wind. And the work on Welles must go on. But how these things are written about is as important as the work of reconstruction, restoration, and “finishing” itself, and that’s

where the issues you raise are still important.

I’m grateful that this interrupted correspondence of ours gives me a chance to look back at Welles’s first great unfinished work and draw some conclusions. Very little has appeared in the press yet about It’s All True, the film. For the most part, as I expected and rather hoped, reviewers have retold the story we told in the documentary, which is essentially the Richard Wilson–Catherine Benamou version of what happened to Welles in Brazil, the reasons for the film not being finished,

and so forth. That serves the first purpose: getting our version of these events out, to counteract the self-serving myth created by the RKO publicity department and recycled by the likes of Charles Higham. Now what about the film Welles was making down there, and the part of it that has survived? As with This Is Orson Welles, where reviewers mostly wrote about the preface rather than the book, the film is being swallowed up by the tale of its long finishing, which at least has a happy ending. But the film is much more subversive than its preface.

“Four Men on a Raft,” the only part of It’s All True that could be finished, is still a political film — or at least it will be when it opens in Brazil tomorrow, where the descendants of the jangadeiros Welles filmed are worse off than their ancestors fifty years ago. Then, they were poor; today, pushed off the beach into favelas by real estate developers and faced with industrial fishing and worse — new forms called predatory fishing that are exhausting their traditional fishing grounds — they see their very way of life threatened with extinction. Yet, when four men very much like the ones you see in the film sailed on a jangada from a village near Fortaleza to Rio in April–May–June of 1993, while we were working on the editing of the film, the President of Brazil wouldn’t even meet with them to hear their grievances. When I spoke to him, Welles was very concerned about how films date; he would be happy to know that “Four Men on a Raft” is one of the few militant films that escapes Daney’s Law: that good militant films only arrive when they are no longer needed. This one seems to have arrived just in the nick of time.

“Four Men on a Raft,” the only part of It’s All True that could be finished, is still a political film — or at least it will be when it opens in Brazil tomorrow, where the descendants of the jangadeiros Welles filmed are worse off than their ancestors fifty years ago. Then, they were poor; today, pushed off the beach into favelas by real estate developers and faced with industrial fishing and worse — new forms called predatory fishing that are exhausting their traditional fishing grounds — they see their very way of life threatened with extinction. Yet, when four men very much like the ones you see in the film sailed on a jangada from a village near Fortaleza to Rio in April–May–June of 1993, while we were working on the editing of the film, the President of Brazil wouldn’t even meet with them to hear their grievances. When I spoke to him, Welles was very concerned about how films date; he would be happy to know that “Four Men on a Raft” is one of the few militant films that escapes Daney’s Law: that good militant films only arrive when they are no longer needed. This one seems to have arrived just in the nick of time.

I hope there will be a debate in Brazil, and that we will be allowed to add our two cents to the jangadeiros’ side. An American journalist working on the story of the 1993 voyage told me the attitude of the Brazilian right: that these people, and their way of fishing, are anachronisms and that Brazil has enough problems without trying to preserve a way of life 400 years old. They’re not wrong about their facts, and the facts are worth remembering. Actually, we interviewed the descendants of the jangadeiros in Fortaleza (with the help of a simultrans system bricolé by our wonderful sound man, Jean-Pierre Duret) without realizing who they really were. And yet all the pieces of the puzzle were in plain view: an invisible people living within the boundaries of a large city, linked by ties of blood and craft, eking out a living as maids or construction workers, but still apart from the larger society, in danger of forgetting their cultural traditions. It was only when Catherine Benamou and I sat down to a surprisingly tasty dinner in a Rio McDonald’s with Aloysio

Pinto, brother of Fernando Pinto, the businessman who financed the 1941 voyage, that the pieces came together.

“The people you interviewed in the Northeast are Indians,” said Aloysio, an ethnomusicologist who has spent a lifetime recording their songs and dances. “The raft they sailed on, the hammock in which the boy is buried, are Indian inventions, which existed in the same form before the Portuguese arrived in Brazil.” In fact, the jangadeiros are examples of the caboclo culture that sprang from the intermingling of the indigenous tribes with black slaves, although the aridity of the Northeast, as Aloysio explained to us, kept the Indian bloodlines purer, because the colonists there were too poor to be able to afford many slaves. The crew of the raft that sailed in 1941 were two black men, Tatá and Manuel Preto (“The Black”), led by two men who look to me like fullblooded Indians, Jeronimo and Jacaré — the São Pedro symbolizes caboclo culture, for anyone who is attentive to the images of Welles’s film. But everything about that raft was already a symbol.

What we have said to the Brazilian journalists we’ve met here is that the jangadeiros of Fortaleza were anachronisms when Welles met them in 1942, and that was certainly the reason he filmed them. He had just filmed Ambersons, the story of a world that disappeared before he was born, and he was in the midst of filming the people’s Carnival in Praça Onze, a public square that had been demolished by the government to make way for Getulio Vargas Boulevard, which he was therefore

obliged to reconstruct in a studio for the filming of “The Story of the Samba.” Welles was not a radical, even though there were radical writers around him in Brazil; he was a man of many nostalgias, whose greatest film, made a quarter of a century later, is a film of nostalgia and regret at the passing of the “merry old England” of Falstaff. Don Quixote, he told me, had taken so long to finish that it could not be finished as a film about the Eternal Spain, but only as a meditation on its disappearance. Maybe that’s what he was really waiting for.

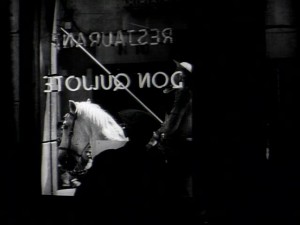

Today, we were told by our friends in Fortaleza that the Castelo Encantado favela where many of the jangadeiros live is slated for demolition to make way for the Avenue of the Jangadeiros, a name which will have a certain allure for tourists coming to this city where every imaginable adjunct of their leisure activities, from the beach towels at our hotel to the annual beer festival, is decorated by the triangular sail of the jangada. Welles would certainly have appreciated the irony of real heroes still living, invisible and in danger of annihilation because of their invisibility, in a town where their rafts have become the totem of tourism, like his Don Quixote and Sancho Panza riding past a shop window displaying Don Quixote knick-knacks and even beer bottles bearing their likenesses.

Today, we were told by our friends in Fortaleza that the Castelo Encantado favela where many of the jangadeiros live is slated for demolition to make way for the Avenue of the Jangadeiros, a name which will have a certain allure for tourists coming to this city where every imaginable adjunct of their leisure activities, from the beach towels at our hotel to the annual beer festival, is decorated by the triangular sail of the jangada. Welles would certainly have appreciated the irony of real heroes still living, invisible and in danger of annihilation because of their invisibility, in a town where their rafts have become the totem of tourism, like his Don Quixote and Sancho Panza riding past a shop window displaying Don Quixote knick-knacks and even beer bottles bearing their likenesses.

What his film makes visible is the jangadeiros themselves, and their way of life. What his film says, and what we have said every time we’ve spoken to the Brazilian press, is that that way of life has value precisely because it is an anachronism, founded on a harmonious relationship with the natural world that we have lost. Today, the jangadeiros and their allies, like the late Chico Mendes and his allies, use ecological arguments: whereas the predatory fishermen who dive for lobsters

(drugged on marijuana because their employers don’t give them wetsuits to protect them against the cold) take everything including the young, the jangadeiros have always known what to take and what to leave so that the species can continue to propagate. Harmonious relations of man with Nature, and, I might add, of man with man. The marginal or artisanal fishermen of every stripe along the Atlantic Coast have in their heads a complex webwork dividing up the sea into territories where each fisherman has the right to fish. The industrial fishing boats and the predators ignore this web, which is invisible because it is woven of oral traditions, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist.

Of course, Welles doesn’t show that. His way of expressing the idea of the collectivity is through what our editor Ed Marx calls “convergence”: the community converging in the cove where the drowned boy has washed up, or at the top of the hill where he is buried; the “orchestra with a moving conductor” (Ed’s expression again) of the political debate, where the camera hops around from one speaker to another as

each in turn becomes the center of a little group of listeners, who are scattered among the drying sails until a larger group coalesces, first around Jacaré’s double, then around Tatá, Jeronimo and Manuel Preto as they decide abruptly to sail to Rio and set off to Francisca’s hut to tell her, followed by the entire community; and in the last scene, the fleet of vessels converging on the lone jangada sailing into Rio Harbor. A symphonic conception of montage, based on the idea of the whole rather than the fragment — the terms Welles used, Catherine tells me, in an article from the 1940s that I haven’t read, to describe the difference between his conception of cinema and Eisenstein’s.

Welles also doesn’t show the other network of social relations that bound the jangadeiros to the bourgeoisie of Fortaleza. Not only did Fernando Pinto raise money to finance the expedition; when the raft set sail, both communities turned out to watch, and choirs from the local seminary sang hymns on two platforms erected for the occasion; a fleet of jangadas saw them out to sea, and planes sent out by the harbor authorities followed their voyage, while journalists, led by a radical of jangadeiro origins, Edmar Morel, pumped up enthusiasm for their exploit through newspaper and radio coverage, until a fleet of modern vessels came out to greet them in Guanabara Bay. Welles leaves all that out, and when he films the jangadeiro colony on Mucuripe Beach, he finds angles that erase the flourishing modern city around them, except for one shot, which we used, which shows the returning fishermen on the beach at sunset with a silhouetted battleship in the background. Those omissions add up to a strong misreading of the Flaherty tradition, with

which he is aligning himself against Eisenstein — Eisenstein, whose influence is visible in every shot, and especially in those close-ups you think we overused, on the evidence of Welles’s other films. But I don’t think there is another Welles film quite like this one.

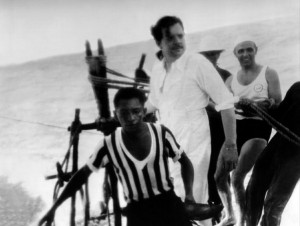

We chose the same approach, in a way, in our documentary preface, which focuses on Welles and tells the story from his point of view. There is another documentary to be made about the jangadeiros themselves, who continued making voyages after Welles left, and even planned to build a big raft to sail to Hollywood to see him one more time before they died and ask him why the film was never finished. Maybe we’ll make that one some day, but in this one we chose to tell the story of an invisible people being filmed by a filmmaker who was himself on the way to becoming, as you say, invisible: here is the result. Through the images of his film we can still read the other text, the one written by the jangadeiros in the breathtaking trajectory of their voyage, which symbolized their desire to become part of the Brazilian nation. They were using the only means of communication available to them; so was he, when he filmed in Fortaleza with a silent Mitchell and the whole improvised apparatus you see in the documentary, and the experience transformed his cinema.

I’m happy with our choices, which I assure you were made after trying just about all the possibilities. One which I never liked enough to really explore it was to play games with the title — I always felt that the title would play games with us without our making any special effort, and it did. For political reasons, we chose to give a false date for when the negative was found (in fact, I’m not sure myself of the real one), but it was a sheer mistake to identify the newsreel images of the Kane premiere at the beginning as Hollywood, when they are really Times Square. So the narrator’s first and last words — “Hollywood, 1941” and “Then, in 1985 . . .” — are false, a symmetry which pleases me no end.

I’m happy with our choices, which I assure you were made after trying just about all the possibilities. One which I never liked enough to really explore it was to play games with the title — I always felt that the title would play games with us without our making any special effort, and it did. For political reasons, we chose to give a false date for when the negative was found (in fact, I’m not sure myself of the real one), but it was a sheer mistake to identify the newsreel images of the Kane premiere at the beginning as Hollywood, when they are really Times Square. So the narrator’s first and last words — “Hollywood, 1941” and “Then, in 1985 . . .” — are false, a symmetry which pleases me no end.

If we made a big mistake, it’s one that I think you and I may also have made in our long polemic, which any good polemicist risks incurring. I mean special pleading, of course — we’ve discussed this. I’ve told you about the sudden doubt that seized me when I saw Montparnasse 19 for the first time last fall: Becker’s portrait of Modigliani made me wonder if we — you and I — haven’t been blinded in our own way to the reality of the man we’ve been writing about all these years by the necessity of making a defense of him that will satisfy, or at least refute his accusers, when an artist’s acts are to be judged in another court altogether, by laws which we only dimly understand.

And I’ve tried to convey to you the vertigo that sometimes seized me when we were plowing through the mass of documents on the making of It’s All True, the difficulty of knowing what happened and why, particularly when we were in Brazil. No one we interviewed in Fortaleza, even Welles’s friends in the local bourgeoisie, could tell us what was in his head while he was shooting “Four Men,” clearly because he had never confided in them, but at least in Fortaleza you didn’t feel as if the ground was about to open under your feet every time you took a step. In Rio, perhaps because of something about the place itself, you did.

And I’ve tried to convey to you the vertigo that sometimes seized me when we were plowing through the mass of documents on the making of It’s All True, the difficulty of knowing what happened and why, particularly when we were in Brazil. No one we interviewed in Fortaleza, even Welles’s friends in the local bourgeoisie, could tell us what was in his head while he was shooting “Four Men,” clearly because he had never confided in them, but at least in Fortaleza you didn’t feel as if the ground was about to open under your feet every time you took a step. In Rio, perhaps because of something about the place itself, you did.

Take the famous furniture-throwing incident, which isn’t in the documentary for good reasons. We know that before leaving Rio to film in Fortaleza, after RKO had publicly disowned him in the Brazilian press, Welles threw some furniture out of the window of a room he had been living in, attracting a crowd and bad notices in the local press. We have two eyewitness accounts: Betty Wilson, who was outside, looking up at the window as a sofa poked out and, after a moment of hesitation, was

withdrawn, and a waiter who walked in while the thing was going on. And we have George Fanto’s recollection of Welles telling the story in the plane on the way to Fortaleza, laughing so hard that the plane shook and the three surviving raftsmen took off their shoes in preparation for a crash at sea. But none of our research was able to establish whether the incident took place at the Copacabana Palace Hotel or at a nearby apartment which Welles was also renting, or even, supposing that it

was the hotel, which room: we were shown one overlooking the street, but we were also shown one overlooking the pool, which is where the more colorful accounts say the furniture landed, with a great splash.

It was like that all the time in Rio. Not only were we shown two hotel rooms; we were shown two apartments, and two houses where Herivelto Martins entertained Welles and Grande Otelo till the wee hours of the morning while they planned the next day’s shooting, not to mention two bars near the Casino Urca where Welles went in protest to join his non-white friends when they weren’t allowed to attend his birthday broadcast at the casino in honor of Vargas’s birthday. Then there’s the story Catherine heard in Bahia about a furniture-throwing incident that allegedly happened there. How many times did it happen? I’m not sure, and I certainly couldn’t tell you why it happened, although I’ve heard as many explanations as I’ve heard reasons for Jacaré’s death, which occurred in broad daylight in front of witnesses. We can assume that the New York Times story that he was eaten by a shark, at least, is untrue, although Welles himself repeated it to Peter, so that you had to cut it out of the book.

My powers of description are simply inadequate to convey the experience of walking around Rio with the Brazilian filmmaker Rogerio Sganzerla, the first person to research this subject, who can show you all the places where everything happened, including the lovely canal (today reeking with sewage) where the government supposedly dumped the Macumba footage that Dick said was never shot. The nonstop vertigo is partly caused, I’m absolutely sure, by something about Rio itself, and partly by the fact that Rogerio and I have to communicate in French, which he doesn’t speak very well — not to mention the brilliant associative patterns of Rogerio’s mind, which I only began to appreciate when we played back our interview with him, accompanied by Catherine’s voice-over translation.

That’s why I recommend, if you want another version of the making of It’s All True, that you look at Rogerio’s two films about it, Nem Tudo e Verdade and Linguagem de Orson Welles. We all know Nem Tudo’s faults, but at least Rogerio tried — for example, in his dramatization of the furniture-throwing incident — to give a well-rounded portrait of the artist as Dionysus, one that supplies a needed corrective to our filmed brief for the defense. And I’m very eager for people to see Linguagem de Orson Welles, Rogerio’s short sequel to Nem Tudo, which as far as I know has never been shown anywhere.

Not having access, as we did, to Welles’s own images and his voice, which we got from Peter’s tapes and the BBC archives, Rogerio used what was ready to hand in his short: mainly the Brazilian newsreels, which he was the first to unearth; and a color film made in the 1960s about the jangadeiros; and for the voice, statements by and about Welles read by Grande Otelo and sound-bites from the films and radio plays.

Unnarrated, the stew of sound and picture Rogerio concocted gives off a powerful aroma of paranoia, with Welles as the sacrificial victim. He even manages to insinuate, as an impression spun off a series of aural and visual associations, the conspiracy theory of Jacaré’s death, which he shares with angrier members of the family of the deceased. And indeed, is it just a coincidence that when the drowning occurred, the press was elsewhere, covering a photo opportunity thoughtfully supplied by President Vargas? I couldn’t say.

Like any essay film worthy of the name, Linguagem de Orson Welles is really a lyric poem, one which concludes with a trouvaille that is breathtaking in its simplicity and efficacy: over images of jangadeiros fishing and of one big fish, in particular, being hauled in and killed, Rogerio plays in its entirety John Huston’s emotional statement to the press on the day of Welles’s death, which recounts Welles’s difficulties in Hollywood and his greatness of spirit in confronting them, accompanied by Dori Cayimi’s “The Jangada Came Home Alone,” one of the songs Welles was thinking of using in “Four Men.” The concluding montage of Welles and Brazil (which ends mysteriously on a shot of the Empire State Building) is accompanied by “Auld Lang Syne,” in Brazilian. Ave atque vale: all the phantoms — so many phantoms — exorcised and laid to rest. I hope I’ll have a chance to write at greater length about this perfect little film in the catalogue of the Locarno festival, where Marco and I plan to show it on a double bill with It’s All True this summer.

Like any essay film worthy of the name, Linguagem de Orson Welles is really a lyric poem, one which concludes with a trouvaille that is breathtaking in its simplicity and efficacy: over images of jangadeiros fishing and of one big fish, in particular, being hauled in and killed, Rogerio plays in its entirety John Huston’s emotional statement to the press on the day of Welles’s death, which recounts Welles’s difficulties in Hollywood and his greatness of spirit in confronting them, accompanied by Dori Cayimi’s “The Jangada Came Home Alone,” one of the songs Welles was thinking of using in “Four Men.” The concluding montage of Welles and Brazil (which ends mysteriously on a shot of the Empire State Building) is accompanied by “Auld Lang Syne,” in Brazilian. Ave atque vale: all the phantoms — so many phantoms — exorcised and laid to rest. I hope I’ll have a chance to write at greater length about this perfect little film in the catalogue of the Locarno festival, where Marco and I plan to show it on a double bill with It’s All True this summer.

Which brings me to my other pet project, one that we’ve discussed many times: The Orson Welles Oral History Project. I think few would dispute that Welles is a large enough and important enough subject to merit his own oral history project, if an institution can be found to house it and money to fund it — it wouldn’t take that much. A first step would be to assemble all the films, tapes, and recordings of interviews that have already been done, by Leaming, Brady, Higham, Bogdanovich,

the authors of that two-volume book about Welles in Spain that you got in the mail, and anyone else who has written about Welles, or made a documentary: certainly Gary Graver’s hilarious Working with Orson Welles, which conveys, as only Gary could, what it was like making The Other Side of the Wind, and Ciro Giorgini’s Rosabella, about Welles in Italy, with all their outtakes — not to mention ours. After that it would be time to fill in the gaps, by sending out an underpaid army of students with tape recorders to interview the surviving witnesses in Yugoslavia, Ireland, England, Argentina, etc. etc., before what happens to all the witnesses in Mr. Arkadin happens to them.

Then, at least, when a real biography of Welles is finally written, the author will have something besides newspaper accounts to base it on, and it will all be in one place. You know who I think should write that one — despite your avowed distaste for biography as a genre. In any case, we both agree that the job remains to be done, and that whoever does it is going to need all the help he can get.

As always,

Bill