Originally written as the tenth chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000), this is also reprinted in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles. Because of the length of this essay, I’m posting it in two installments – J.R.

3. The taboo against financing one’s own work. I assume it’s deemed

acceptable for a low-budget experimental filmmaker to bankroll his or

her own work, but for a “commercial” director to do so is anathema

within the film industry, and Welles was never fully trusted or respected

by that industry for doing so from the mid-forties on. This pattern

started even before Othello, when he purchased the material he had

shot for It’s All True from RKO with the hopes of finishing the film

independently, a project he never succeeded in realizing. As an

overall principle, he did something similar in the thirties when he

acted in commercial radio in order to surreptitiously siphon money

into some of his otherwise government-financed theater productions

during the WPA period, a practice he discusses in This Is Orson

Welles. John Cassavetes, who also acted in commercial films in order

to pay for his own independent features, suffered similarly in terms of

overall commercial “credibility,” which helps to explain why he and

Welles admired each other. (In an early stage of his work on the

unrealized The Big Brass Ring, a late script and project, Welles

thought of casting Cassavetes and his wife Gena Rowlands as

presidential candidate Blake Pellarin, the hero, and his wife, Diana.)

In the case of features that were largely financed out of Welles’s own

pocket, such as Don Quixote and The Deep/Dead Reckoning,

Welles often insisted in interviews that when or if he finished and

released these features was nobody’s business but his own — an

attitude that often met with resentment and/or incomprehension

from his fans. This raises a good many intriguing and not easily

resolvable questions about the implied social contract that exists

between artist and audience, and one that is undoubtedly inflected

by the relative power of the industry to deliver films to theaters and

the relative powerlessness of most film artists to ensure that their

own films get distributed.

In Welles’s case, the poor critical receptions and poor business that

greeted most of his releases, at least in the United States, made him

understandably hesitant to risk whatever remained of his “bankability”

by releasing any of his films prematurely, or at the wrong time; he was

also handicapped throughout his career by being a terrible business-

man and often made wrong guesses about the commercial viability of

some of his projects. I’m told that he once turned down a relatively

generous offer from Joseph Levine to distribute F for Fake in the United

States, an offer Levine made even though he had nodded off during a

screening; convinced that his film would be a big moneymaker, Welles

turned him down flat, only to accept a less lucrative offer years later in

order to get any American distribution at all.

When I asked him about Don Quixote in the early seventies, he replied

that Man of La Mancha was currently being developed as a movie and

he didn’t want his own version to compete with it. This statement

astonished me at the time, but after I reflected on all the abuse he

received from the American press about the inferiority of his Macbeth

to Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet, I began to think his fears might have

been justified. (When I asked him about The Deep, he insisted that it

was the sort of melodrama that wouldn’t date, and that he was more

interested in releasing The Other Side of the Wind first — although

this eventually proved to be impossible for legal and financial reasons

that are documented in Barbara Leaming’s Welles biography.)

4. The unique forms of significant works. It surely isn’t accidental

that we have only one completed version of Citizen Kane to evaluate.

By contrast, we have at least two completed versions of Welles’s

Macbeth, three versions of his Othello, and at least four versions

apiece of his Mr. Arkadin and Touch of Evil, to provide only a

short list. (There’s also, for example, a separate version of The Lady

from Shanghai that has circulated in Germany containing some

takes as well as shots that are different from those in the U.S. release

version.)

The reasons for this confusing bounty are multiple, but all of them

ultimately stem from Welles’s unorthodox practices as a filmmaker.

When early audiences and critics complained about the Scottish

accents and the length of the first version of Macbeth (which is

incidentally the one principally available today), Welles obligingly

had the film redubbed and deleted two reels’ worth of material.

(Most critics assume mistakenly that the only Hollywood film on

which he had final cut was Kane; in fact, he also had final cut on

both versions of Macbeth, even if the second version was done at

the behest of Republic Pictures.)

Othello, on the other hand — Welles’s first completed independent

feature — was partially reedited and redubbed at Welles’s own initiative,

between the time of its Cannes premiere and its belated U.S. release

over three years later. Although you won’t find this information in any

of the “authoritative” books about Welles, French film scholar

François Thomas has recently discovered that Welles redubbed

Desdemona — played in the film by Suzanne Clothier, who shot her

sequences in 1949 and 1950 — with the voice of Gudrun Ure (later

known as Ann Gaudrun), the actress who played Desdemona in his

subsequent 1951 English stage production of the play, entailing a

different interpretation of the same part. Over forty years later, long

after Welles’s death, the sound track of this second version was

significantly altered — both sound effects and music were rerecorded

in stereo, in the latter case without consulting composer Francesco

Lavignino’s written score, and the speed of the dialogue delivery was

occasionally altered to improve the lip sync — in order to release the

results as a so-called “restoration.”(8)

____________________________________________

[8] In the cases of both Mr. Arkadin and Touch of Evil, Welles never had final cut on any version, so all of the existing versions represent different attempts to realize his intentions after the film slipped out of his control. (Arkadin was taken away from him at a relatively early stage in the editing, Touch of Evil at a relatively late stage.) For a more detailed critique of the third version of Othello — the only one readily available in the United States thanks to the pressures of Welles’s youngest daughter, Beatrice, who maintains legal control of this film — see “Othello Goes Hollywood” in my collection Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, pp. 124–132) and Michael Anderegg’s excellent Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, pp. 111–120).

Though it’s theoretically possible to assign different evaluations to

the separate versions of Macbeth and Othello, critics have rarely

bothered to carry out this work; in fact, most of them have been

unaware that these separate versions exist. The fact that both

versions of Macbeth and the first two versions of Othello were

all Welles’s own handiwork means that we can’t rank them in terms

of authenticity (except to note that the second Macbeth wasn’t

instigated by him). We can’t, for instance, argue that the

European Othello is “more Wellesian” or “truer to Welles’s

intentions” than the initial U.S. version, and consequently it

becomes impossible to speak of a “definitive” film version of

Welles’s Othello.

The same principle was carried out more publicly by Jean-Marie

Straub and Danièle Huillet — a European couple who make rigorous

and beautiful avant-garde films that, in recent years, have rarely been

screened in the United States — when they deliberately released four

separate versions of their 1986 feature The Death of Empedocles,

each employing separate takes of each shot, to correspond to the

separate languages of each version: unsubtitled German, English

subtitles, French subtitles, and Italian subtitles. Straub argued that

this was done in order to challenge the notion of uniqueness that we

habitually assign to individual films, and he certainly had a point,

but Welles made the same point more offhandedly and surreptitiously

three decades earlier when he refashioned his second Othello without

bothering to announce that he was doing so.

Why, one may ask, did Welles do this? Because he loved to work,

one might surmise, and because for him all work was work-in-

progress — both reasons helping to explain why he often wound up

having to finance much of the work himself. To love the process of

work to this degree evidently offends certain aspects of the Protestant

work ethic. Judging from the jibes about Welles’s obesity in his later

years that often cropped up in his American obituaries — but not in

most obituaries that appeared elsewhere in the world — Welles’s

reputation as a hedonist was often used against him to imply

irrationally that all his production money went to pay for expensive

meals; indeed, many people preferred to believe that the only reason

he didn’t make or finish or release more films was out of laziness and

moral turpitude. (This is more or less the thesis of biographers Charles

Higham, David Thomson, and, to a lesser extent, Simon Callow, none

of whom ever met the man.)

Obviously the fact that Welles loved to make films — and often sacrificed

his reputation as an actor by appearing in lots of TV commercials and

bad movies in order to keep doing so — doesn’t square with this

hypothesis, except to imply that to some degree he wound up

tarni0shing part of his public profile in order to subsidize his art. The

process by which a public figure became a private artist is obviously

fraught with contradictions, but one should never forget that it was

love of the art-making process itself that ultimately sabotaged

Welles’s commercial profile. And as the Chilean-French filmmaker

and devoted Welles fan Râùl Ruiz once said to me, in defense of

Welles’s reputation as a maker of unfinished films, “All films are

unfinished —except, possibly, those of Bresson.” Which leads us

logically to

5. Incompletion as an aesthetic factor. Critics confronting Franz

Kafka’s three novels have less of a problem with this — at least Kafka is

rarely castigated as an artist to the degree that Welles is. Could this be

because money is involved more centrally with making movies than

with writing novels? It’s also important to recognize that no two of

Welles’s unfinished films remain unfinished for the same reason. This

is the portion of Welles’s oeuvre that’s most notoriously difficult to

research, but on the basis of what I’ve been able to glean over the years,

Welles wanted and made repeated efforts to finish both It’s All True

and The Other Side of the Wind, came close to finishing Don

Quixote in at least one version in the late fifties (according to former

Welles secretary Audrey Stainton; see her article, “Don Quixote: Orson

Welles’s Secret” in the Autumn 1988 Sight and Sound), and eventually

abandoned The Deep for personal as well as commercial reasons.(9)

[9] One film commonly described as unfinished — Welles’s forty-minute condensation of The Merchant of Venice, his only Shakespeare film in color, designed in the late sixties to serve as the climax to a CBS TV special — was in fact fully edited, scored, and mixed, though most of it was spirited away by an Italian editor after a single private screening; one hopes that eventually the full version will see the light of day. Nine minutes of this film are currently held by the Munich Film Archive. Two other completed short films — Camille, the Naked Lady, and the Musketeers (1956) and Viva l’Italia! (aka Portrait of Gina, circa 1958) — are unsold, half-hour TV pilots; the first of these is lost, though the second resurfaced three decades later, and was recently shown in its entirety on German TV. Needless to say, the list goes on. . . .

So much for incomplete works — which doesn’t, of course, include

features wrestled away from Welles’s control and completed by others,

such as The Magnificent Ambersons and Mr. Arkadin. But what

about the incompleteness of Welles’s oeuvre as a whole, an even more

serious problem due to the unavailabilty of so many of his works,

finished and unfinished alike? Some of these, like the films he made as

integral parts of stage versions in the thirties or the portions of features

(The Magnificent Ambersons, The Stranger, The Lady from

Shanghai) deleted by studios, are almost certainly lost for good. Some

films, such as his first and best TV pilot (The Fountain of Youth,

1956) and Filming “Othello” (1979), remain unavailable simply

because of “business reasons” (i.e., the indifference of the copyright

holder or legal obstacles, which often amount to the same thing),

with the result that most American viewers are scarcely aware of

their existence. Three extended TV series made by Welles in Europe

— Orson Welles Sketch Book (six 15-minute episodes, 1955),

Around the World with Orson Welles (five completed half-hour

episodes and one unfinished episode, 1955), and In the Land of

Don Quixote (nine half-hour episodes, 1964) — survive but remain

unavailable in the United States. [2014 postscript: The second of these

is now available on DVD.] And most of the unfinished work has wound

up in film archives—the Fortaleza footage of It’s All True at UCLA

(although the footage that survives from that feature continues to be

in peril until funds are found to preserve it), Don Quixote and In the

Land of Don Quixote at the Filmoteca Española in Madrid,

and, most recently, a varied collection of unfinished work (including

The Deep, Orson’s Bag, The Magic Show, and The Dreamers)

at the Munich Film Archive, which is still seeking ways of restoring and

presenting it.

Without implying that all this material is equally important or interesting

— I regard most of In the Land of Don Quixote as amiable hackwork

at best — I would argue that a significant part of it, judging from the

portions that I’ve seen or sampled, substantially alters one’s sense of

Welles’s oeuvre as a whole, extending its range and diversity while

illuminating certain work that one already knows. This ultimately

means that, fifteen years after his death, we are still years away from

being able to grasp the breadth of Welles’s film work, much less

evaluate it.

6. A confounding of the notion of art as commodity. We’re finally left

with the problem of how to evaluate Welles’s still-ungraspable

oeuvre in relation to the international film market — an issue that is

currently preoccupying a good many film executives as well as

archivists considering the possibility of completing and/or

releasing films by Welles that haven’t yet been seen. Prior to the

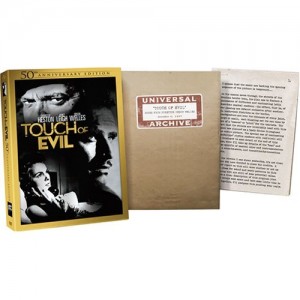

very successful commercial release of the reconfigured Touch

of Evil, the prospects of getting any of these films out on the

world market was beginning to look rather dim. (To date,

Jesus Franco’s lamentable version of Welles’s Don Quixote

— hastily edited in order to premiere in a Spanish-language

version at Spain’s Expo 92, and subsequently completed in an

English-language version as well — has failed to find a

U.S. distributor; to the best of my knowledge, it has only

received a few scattered screenings in North America,

most notably at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.)

Now that the commercial prospects are looking

somewhat more favorable, numerous questions

still remain — including how these “new” (or “old”)

works are to be represented.

“Welles’s Lost Masterpiece” was the phrase used in ads for the

significantly altered version of Welles’s 1952 Othello released

in 1992 — although the film had never been lost at all; it had

simply been out of distribution in the United States for many

years. The new version, moreover, was billed as a “restoration,”

and this was how it was labeled by a good ninety-five-percent

of the reviews in the press; in The New York Times, for

instance, Vincent Canby called it “an expertly restored print that

should help to rewrite cinema history.” But as Michael Anderegg

has pointed out,

To term the project authorized by Beatrice Welles-Smith as a ‘restoration’ is to make nonsense of the word. One cannot restore something by altering it in such a way that its final state is something new. To restore means, if it means anything, to bring back to some originary point — itself, of course, an extremely dubious concept. . . .

If you find a Greek statue with a left arm missing, you might be able to restore it if, (a) you can demonstrate, through internal and external evidence, that it once had a left arm and (b) you can discover some evidence of what the left arm looked like when it was still attached. If, however, the statue was meant to have no left arm (a statue, perhaps, of a one-armed man), or if the statue was never completed by the sculptor, or if, assuming the arm did once exist and had broken off, you have no evidence of what the missing arm had originally looked like, then adding an arm of your own design is not an act of restoration. You are, instead, making something new.(10)

___________________________________________

[10] Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture, op. cit., p. 112.

According to Anderegg’s subsequent analysis, the version of Welles’s

Othello described as a “restoration” alters not only Welles’s original

sound design and Francesco Lavignino’s score, but also reloops some of

the dialogue with new actors, eliminates some words “so that a lip-synch

could be achieved,” and reedits one sequence entirely. But of course the

use of the term “restoration” in relation to movies has become so loose

and imprecise in recent years that it characteristically gets employed

every time a studio decides to strike a new print, add footage without

consulting the original director, or, on a few rare occasions, rework an

old movie with the original director’s input (as in the rereleased

Blade Runner, which proved to be partly a restoration of Ridley

Scott’s original cut and partly a revision — including the insertion of a

shot of a unicorn taken from Scott’s Legend, a film made three years

after Blade Runner). Typically, the summer before Universal Pictures

released the reedited version of Touch of Evil, it reissued on video the

preview version of the film that had already been available since the

seventies and mislabeled it not only a “restoration” but the “director’s

cut,” which was even more ridiculous — adding insult to injury insofar

as Universal had never allowed Welles to complete a final cut of his own

in the first place, which in fact is what occasioned his fifty-eight-page

memo to Universal studio head Edward Muhl.

Significantly, in the early nineties, when I originally tried to get an

American film magazine interested in publishing roughly two-thirds

of this memo, a document drafted in 1957, Premiere and Film

Comment both turned me down flat; if memory serves, the former

considered the document far too esoteric and the editor of the latter,

who wasn’t even interested in reading the text, felt that Film

Comment had lately been concentrating too much on Welles.(11)

______________________________________

| [11] More recently, Film Comment reviewed two dubious Welles-related films, Cradle Will Rock and RKO 281, but refused to consider running any reports on restorations of unseen Welles films in Munich. |

For me, the document was fascinating and revealing because it delved

so deeply into Welles’s artistic motivations — something that he was

rarely willing to comment about elsewhere, even in his book-length

interview with Peter Bogdanovich — but this consideration cut no ice

with either magazine. Then, seven years later, as soon as Universal

Pictures had a version of Touch of Evil based on following the

instructions of the memo, the same text suddenly became a hot item,

and Premiere even wound up commissioning me to write a short

article about the new version of the film. (The quarterly Grand Street

also expressed a strong interest in printing excerpts from the memo

until it discovered belatedly — not having grasped the fact earlier,

through a misunderstanding — that excerpts were about to appear in

the second edition of This Is Orson Welles.) The difference in attitudes

was clear: in the early nineties, the text had no “currency” because it

wasn’t tied to any currently marketable item; by the late nineties, it had

suddenly taken on a promotional value in relation to one of Universal’s

upcoming releases.

For more or less the same reason, a lengthy production report in

the Los Angeles Times in 1998 on the upcoming release of George

Hickenlooper’s The Big Brass Ring, based on a much-revised version

of Welles’s 1982 script that had been revamped by film critic F. X.

Feeney and Hickenlooper, went out of its way to disparage Welles’s

original script as something that needed to be updated and reworked

in order to be relevant to a 1999 audience. The reporter gave no

indication of having read the Welles script in order to test this premise;

the article was content to quote actor Nigel Hawthorne reading aloud

from David Thomson’s attack on the script in Rosebud in order to

demonstrate that Welles’s work clearly needed a polish. However

ludicrous this assumption seemed to me at the time, I also realized it

was typical of entertainment journalism. The fact that Hickenlooper’s

movie was shortly to become an item on the marketplace — while the

limited edition of Welles’s screenplay, which had sold out its print run

of one thousand copies shortly after its publication in 1987, was no

longer an item on the marketplace — was the only thing that mattered,

and pre-emptive comparative evaluations of the two were relevant only

insofar as they helped to promote the Hickenlooper feature. (In fact,

Hickenlooper’s film revised the original script so extensively that few

traces of the original remained.)

***

The half-dozen forms of ideological challenge discussed above are by

no means exhaustive when it comes to outlining the continuing

provocation and interest of Welles’s work. But I hope they adequately

suggest the degree to which his work and the various problems it raises

throw into relief many of the issues I’ve been discussing throughout

this book. For generations to come, I suspect, Welles will remain the

great example of the talented filmmaker whose work and practices

deconstruct what academics, taking a cue from the late French theorist

Christian Metz, are fond of calling “the cinematic apparatus.” This is not

necessarily because he wanted to carry out this particular project, but

more precisely because his sense of being an artist as well as an

entertainer was frequently tied to throwing monkey wrenches into our

expectations — something that the best art and entertainment often do.