From the Chicago Reader (September 14, 1990). — J.R.

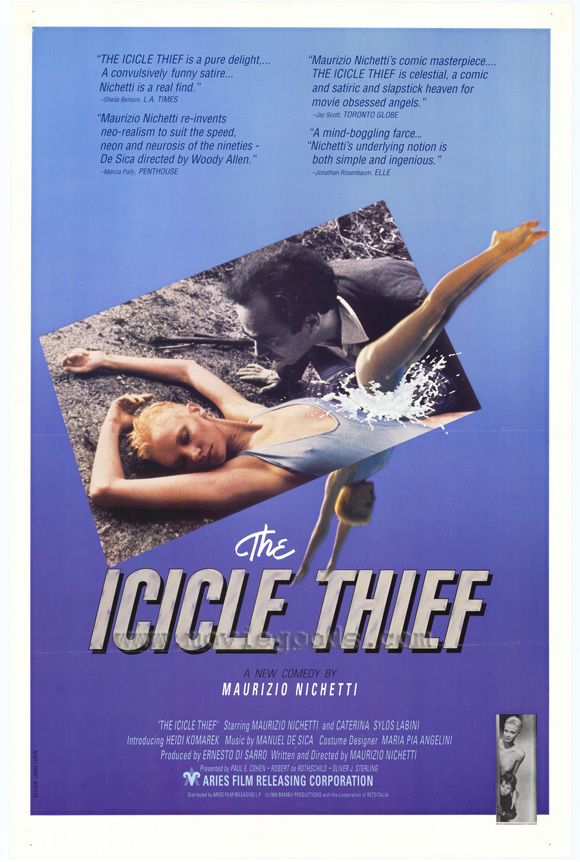

THE ICICLE THIEF

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Maurizio Nichetti

Written by Nichetti and Mauro Monti

With Nichetti, Caterina Sylos Labini, Federico Rizzo, Heidi Komarek, Renato Scarpa, Carlina Torta, Lella Costa, and Claudio G. Fava.

There is still so much we have to learn about TV! — Kurt Vonnegut, Hocus Pocus

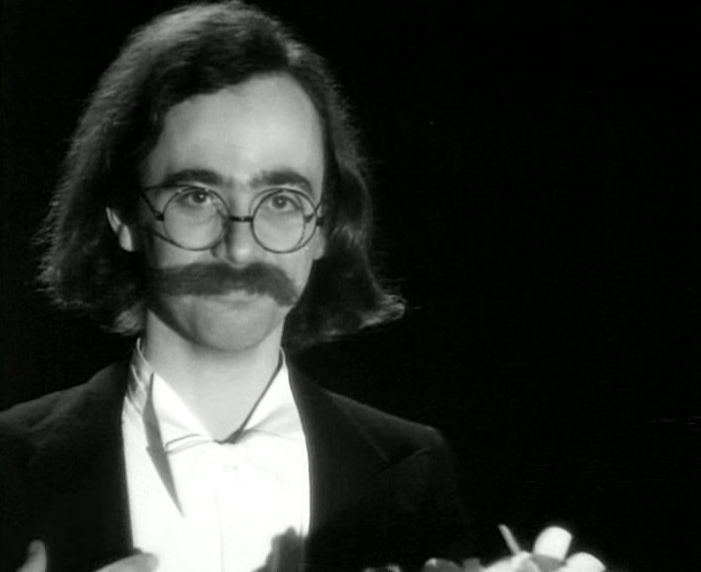

Some people have called Maurizio Nichetti the Italian Woody Allen, an unfortunate appellation in more ways than one. Not only does it not do him justice, it also attributes to him an urban snobbishness that couldn’t be further from his world and persona. In the New York Times, where Allen’s movies are ranked higher than the late works of Welles and Antonioni — apparently because Allen, unlike Welles and Antonioni, reflects the worldview of many New Yorkers — the label can only backfire. But take a look at both actors and ask yourself which of the two is funnier.

The first time I saw a Nichetti movie, all it took was the opening sequence to convince me that there was no contest.

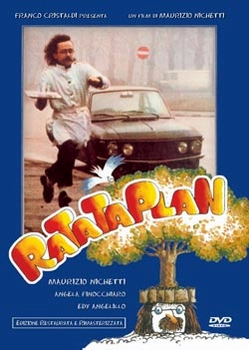

At an international conference in Milan, a distinguished participant suffers a stroke. A desperate call is made across the city to Colombo — a short nebbish with a mop of hair and a Groucho mustache, who operates a hilltop refreshment stand — for a glass of mineral water for the poor man. Colombo hurtles down the hill with his tray and sets off on a heroic journey across Milan, during which, among countless other mishaps, the glass of water is sprayed with exhaust fumes, covered by a policeman’s cap, and speckled with white paint before a bee ceremoniously drowns in it.

This is the opening sequence of a poetic, lunatic farce called Ratataplan (1979), the first feature of director- writer-actor Nichetti (who plays Colombo), the world premiere of which I happened to see quite by chance at the Venice film festival, where it won the Golden Lion, then went on to become a monster hit, running as long as six months in some Italian cities. I was there not for the festival but as a participant in a three-day international conference called “Cinema in the 80s” — a deep-dish Tower of Babel affair devoted to “language, industry, and audience,” where three dozen jet-lagged filmmakers and critics from six countries tried to converse in five languages with simultaneous earphone translations. No one had a stroke, but there were moments when we felt we were drowning in our own gibberish.

After that experience, Ratataplan, a comedy completely without dialogue, was an exhilarating revelation, brushing away all the cobwebs and confusion. Here was the cinema of the 80s–not just a fresh comic vision and film style, but a view of the modern world’s insanity that told me much more than three days of lectures. Some parts of the movie — a weird, absurdist collection of screwball skits — were more successful than others, but the whole thing was fresh and unpredictable. The striking uses of pantomime and sound effects occasionally suggested the influence of Jacques Tati (who, I later learned, adored the film), but the overall effect was original — a portrait of the anomalous present that could only have been conceived by a poet.

Born in 1948, Nichetti trained in architecture and theater before finding work as an acrobat and circus clown. He started out in movies scripting cartoons for animator Bruno Bozzetto, including Bozzetto’s Allegro non troppo (1976). He also appeared in that film, in the live-action linking sequences, as a beleaguered and befuddled animator. But his charming gifts as a clown give no warning of Ratataplan‘s shrewd and singular observations on the peculiarities of contemporary life: they are at once prescient and unpretentious, deceptively simple and provocative. For instance, there’s the scene in which the shy Colombo collects odds and ends from the city dump and puts together a robot replica of himself with a video camera inside the head. Guiding his suave, remote-control double out the door with a fixed steering wheel, like a puppeteer, and picking up its precise point of view on a TV monitor, he manages to make a date with his downstairs neighbor and take her out disco dancing without ever having to leave home.

After writing about Ratataplan for American Film, I was delighted to hear that a small independent U.S. distributor had picked it up. But the movie never opened. I heard that it had been previewed for a few New York critics — our cultural commissars when it comes to national releases of foreign films; they were not amused, so that was that. Four years later, it turned up briefly on cable, its onomatopoeic title (meant to suggest a drum cadence) shortened to Rataplan; but it wasn’t reviewed and it never came out on video.

Years passed. I heard reports of two more satirical Nichetti features — another commercial success in 1980 and then a relative flop in 1982 — after which Nichetti had been working exclusively in Italian TV, creating and appearing in a popular variety show called Quo Vadiz and a long-running kids’ show called Pista (roughly akin to Sesame Street, but done in his own invented language), and directing a good many commercials. I was beginning to wonder whether the humorlessness of a few Manhattan stiffs was going to keep Nichetti’s work off American screens indefinitely.

It took seven years for Nichetti to secure the creative control he wanted to make a fourth feature. The Icicle Thief won the grand prize at last year’s Moscow film festival, and soon after, I saw it in a packed house on the opening night of the 1989 Toronto film festival. It fully lives up to the promise of Ratataplan without any hint of repetition (pantomime and echoes of Tati are no longer apparent), and that joyful North American audience found it hilarious and wonderful. Seeing the movie a month later at the Music Box during the Chicago film festival with an equally rapturous audience, and subsequently learning that the film had been picked up by a small U.S. distributor, I figured it was only a matter of time before Nichetti was declared a comic genius and his other pictures were shown coast to coast, the New York commissars notwithstanding.

Scattered reviews started appearing around January — some enthusiastic, some not — after the movie was previewed in New York, but the film still didn’t open. Is history repeating itself? Knowing how treacherous it is to be a small independent distributor today — competing with a handful of multinational conglomerates that control everything from the MPAA ratings to what gets hyped on Entertainment Tonight — and considering how expensive it is to open any picture in New York, I fear The Icicle Thief may not be around for long. In any event, now that it’s finally playing in Chicago as well as New York, I suggest that you see it as soon as possible. If you wait too long, you risk missing what is probably the best and funniest Italian comedy of the past decade.

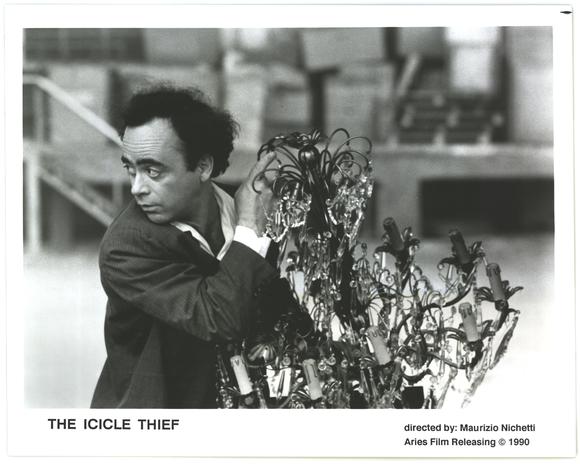

Part of the brilliance of The Icicle Thief — which charts the gradual interfacing of three separate plots — is that it’s much easier to watch than it is to describe. The three separate yet connected stories involve a real-life TV program that shows movies, the family in a movie showing on the program, and a family watching the program. Nichetti, this time playing himself, arrives at a TV studio in Milan where the movie program is about to present his latest film — The Icicle Thief, a black-and-white hommage to De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief (1948) about an impoverished family struggling to make ends meet in the postwar era. (In the movie within a movie, Nichetti, without a mustache, plays the out-of-work father, Antonio Piermattei.) Claudio G. Fava, a real-life film critic who hosts this real-life film show, is grumpy about having to present Nichetti’s film, which he hasn’t seen, rather than either of the two films he’s prepared spiels for: John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s L’armée des ombres (1969). This doesn’t prevent him, however, from rattling on about the beauty and sincerity of The Icicle Thief.

Meanwhile, a typical middle-class Italian family — father, pregnant mother, and two kids — finish up their dinner and start distractedly to watch the movie. The mother (Carlina Torta), who thinks she may have seen the film before, complains that Fava is giving away too much of the plot, and she spends time on the phone with her mother chatting mainly about pumpkin pasta; the father reads a magazine, and generally pays attention to the screen only when there’s a hint of sex; the little boy is busy with his Lego set; and the little girl is scarcely to be seen.

The movie begins, and it’s actually closer to an affectionate pastiche of Italian neorealism than a parody, and adequate rather than brilliant as such, though it does contain a few wry variations on its models. It gradually becomes apparent that one reason the family is so impoverished is that the parents are both fairly lazy: Maria (Caterina Sylos Labini), hoping to make it in show business, spends all her time rehearsing with a trio of singers in a nightclub, leaving her infant son playing on the floor with, among other things, loose electrical wiring. The father, Antonio, makes the rounds on his bicycle looking for a job, but it is their cherubic little boy Bruno (Federico Rizzo) — who works in a filling station and appears to do most of the cooking and house repairs — who seems to be the principal laborer; even the local priest (Renato Scarpa) hands him a mop and pail. Maria is hungry for luxuries — she dreams of having a crystal chandelier like one she saw in a movie, with pendants resembling icicles — and her frustration about their poverty leads to many quarrels with Antonio.

Eleven minutes into the movie, it screeches to a halt before the end of a scene (oddly, even the actors seem taken aback), breaking for a string of glitzy color commercials selling American-style images of the good life: candy bars called Big Big, an artichoke aperitif, an all-temperature detergent, and aerodynamic cars. In the studio Nichetti goes into a rage about these cuts and intrusions. We return to the family watching TV, and after the film within the film resumes, it gradually emerges that the one-way communication of TV is starting to become two- way, and that the apparent discontinuity between the film and the commercials is breaking down as well: the little boy, slowly building an elaborate Lego model of the Kremlin, is eating a Big Big candy bar, and Bruno, eating a dinner of cabbage, eyes it greedily from the TV; a bit later, Bruno starts to sing the Big Big jingle to himself, and Antonio and Maria wonder where he heard the song.

Antonio gets a job at a glass chandelier factory, and to please Maria, he steals one of the chandeliers with “icicles” for her. On his way home, there’s another break for commercials; just as a voluptuous model is diving into a swimming pool in the middle of the car commercial, the TV studio suffers a power failure — a power failure that also affects the family watching TV. When the power comes on again, the model, still in color, is drowning in the river, in black and white, that Antonio passes on his way home.

Things get progressively stranger and more intermingled; Maria winds up inside the detergent ad, and her disappearance combined with the strange appearance of the bathing beauty leads to Antonio’s arrest. Aghast at what’s happening to his movie, Nichetti leaves the studio and boards a train that takes him into the neorealist movie, where he tries to straighten things out. For the family distractedly watching all of this on TV, however, everything seems to be perfectly in order.

Superficially, Nichetti’s cockeyed construction resembles that of Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, as well as certain aspects of Gore Vidal’s novel Myron. Allen’s and Vidal’s conceits, which involve the interfacing of movies and audiences, are initially hilarious as well as suggestive, but they both gradually run out of energy and conviction, thanks in part to the increasingly apparent attitude in both works that the mass public is a pack of blithering idiots. Nichetti’s conceits prove to be stronger and more sustaining not only because they lack this condescension, but also because they’re grounded much more firmly in telling observations about movies, TV, and the contemporary audience; anchored in the present rather than the 30s (as in The Purple Rose) or the 40s (as in Myron), their social meanings cut much deeper.

In the last chapter of The Ticket That Exploded, William Burroughs proposes that “what we see is determined to a large extent by what we hear,” and suggests that if we turn off the sound on our TV and arbitrarily substitute any new sound track, the new sound track will not only match and seem “appropriate,” but will also determine our interpretation of the images. I think one could add that the reason his experiment works is the fundamental discontinuity of both TV itself and the way that we watch it. I’m thinking not just of commercials and other forms of program interruption but the interruptions that we commonly impose ourselves — whether we leave the room, engage in other activities, switch channels, adjust the controls, or simply let our attention drift. Sound tracks, story lines, familiar faces, and countless other conventions conspire to make the experience seem continuous, but only an act of massive repression on our part can sustain such an impression.

Family TV watching offers a particularly rich and varied model of how this discontinuity functions. One of Michael Arlen’s best TV columns for the New Yorker (“Good Morning,” collected in The View From Highway 1) simply charts the manner in which a typical middle-class family consumes with their breakfast one morning the news and The Flintstones — alternately and piecemeal, in random bites. Nichetti’s family of TV watchers is similar, and part of his comic point is not just how inattentive TV makes us, but how each of us imposes her or his own agendas and forms of continuity on what’s being intermittently watched.

It’s worth adding, however, that the pre-TV Piermattei family are every bit as distracted and divided in their concerns as the contemporary family watching them — the perpetually neglected baby and his unseen near-calamities are only one example of this — so the issue is not “TV or not TV,” but human nature in relation to fantasy. Indeed, an important part of Nichetti’s humor comes from the similarities between these two families in spite of their radically different circumstances. Consider the unremarked resourcefulness of the two little boys; significantly, Heidi (Heidi Komarek), the model from the car commercial, is the only one in the movie who truly appreciates Bruno, and his mother is the only one who truly appreciates the commercials, though they both live in worlds 30 years apart from the objects of their appreciation.

In a very real sense, of course, the material deprivations of people like the Piermattei family eventually helped to produce the gaudy commercials, and one could argue as well that the environmental and spiritual deprivations of the contemporary family give an exotic allure to the small-town, church-centered community in the movie on TV. In fact, our isolation and independence from other eras is as much of a consumerist myth — dictated by the needs of merchandising — as our assumption of continuity when we’re watching TV; both are convenient fictions that Nichetti’s mischief deliriously unravels.

Another convenient fiction promulgated by commerce that Nichetti playfully deconstructs is the cherished (and profitable) notion that a movie is “the same thing” whether we see it in a theater or on TV. Nichetti repeatedly cuts from the neorealist film as a film to its grainy, reduced definition on a TV screen, and while his character, who rails against the cuts and commercial breaks, never alludes to this degeneration of the image, the visual evidence is unmistakable. This doesn’t mean that he’s arguing for the virtues of one medium over another; as someone who has worked for years in both, he’s clearly attuned to their separate advantages and possibilities, and he’s not blind to their interdependence, either. Ironically, The Icicle Thief was financed by Italian TV and is already scheduled to appear on the same program that the neorealist pastiche appeared on in the film, with Claudio Fava as host.

It won’t be interrupted by any commercials, however — which is just as well, because Nichetti’s commercial pastiches are so convincing (much more so than his imitation of De Sica), who could tell which was which? Although the film’s address is universal, it’s worth delving for a moment into certain conditions that helped inspire it, and that may well have been affected by it in turn. Italy has had commercial TV for only a little more than a decade, and with it came both commercial breaks and a greater number of channels showing old movies. (Commercials hadn’t been absent from state TV, but they were usually shown in autonomous bunches between programs.) One form of commercial interruption was already a central condition of Italian filmgoing; traditionally movies in theaters are broken up into two parts in order to sell ice cream and candy, and Italian directors even structure their movies to accommodate this convention. But the sudden availability of vast numbers of old movies on the tube and the brutally chopped up manner in which they were served had a combined impact on Italian film lovers that continues to reverberate.

In fact, last November, several months after the release of The Icicle Thief, the appellate court in Rome upheld and broadened a lower court’s ruling that private TV networks couldn’t interrupt films with advertising. Stating that these interruptions “alter the identity” of films and therefore violate the rights of their makers, the court declared that “any pause for huckstering destroys the integrity of a film, be it a classic or something a few rungs down the ladder.” (Sadly, the late Otto Preminger failed to effect a similar ruling when he went to court in the mid-60s for the same reason. Today, when huckstering in this country is widely felt to constitute integrity on a legal level rather than violate it, he’d probably be laughed out of court.)

Last year I met Nichetti briefly in Chicago, and he told me about his second and third features, which are so far unavailable here:

Ho fatto splash (Splash, 1980) is also about Colombo, but this time he’s the only character who doesn’t speak. Colombo goes to sleep at the age of six, in 1955, and wakes up 25 years later, unchanged mentally but now played by Nichetti, in a room with his female cousin, who shares a flat with two other women. (One of these women is Carlina Torta, playing the same character as the pregnant mother in The Icicle Thief nine years earlier; in fact, there’s a line in the latter film where she recalls her former flat mates.)

Domani si balla (Tomorrow We Dance, 1982) is a low-budget SF comedy, done in the style of French film pioneer Georges Méliès, about a UFO that comes to earth bringing happiness, specifically music and dance. This proves to be vexing to the people who run TV, who can’t stand the notion of people providing their own amusement. Nichetti (who speaks this time) and costar Mariangela Melato play two rebellious TV reporters who support the aliens. (It sounds like a screwball Italian version of Pump Up the Volume.)

Nichetti’s recently completed The Will to Fly, due out in Europe late this year, combines animation with live action and concerns “a man whose hands take on a life of their own.” Whether you’ll get to see it or Ratataplan or the two other features described above depends, of course, on many arcane factors completely beyond the control of you or me. But if you go to see The Icicle Thief and like it and send your friends, at least you’ll be casting a vote.