Published by Santa Teresa Press (in Santa Barbara) in 1994 (twenty years later, this book is still available on Amazon) and reprinted in Discovering Orson Welles in 2007, along with the following introductory comments:

Critic Dave Kehr once said to me that encountering The Cradle Will Rock after The Big Brass Ring was a bit like encountering The Magnificent Ambersons after Citizen Kane. I appreciate what he meant — especially when it comes to this script’s nostalgia and its sharp autocritique compared to the more narcissistic and irreverent surface of its predecessor. But I hasten to add that this script, unlike The Big Brass Ring, is more interesting for its autobiographical elements than for its literary qualities. Perhaps for the same reason, writing an afterword about it was more difficult.

On the subject of Tim Robbins’s Cradle Will Rock,I’d like to quote excerpts from an article of mine that appeared in the Chicago Reader on December 24, 1999:

For the past seven months, ever since Robbins’s movie premiered in Cannes, friends and associates who saw it there have been warning me that I, as an Orson Welles specialist, would despise it. Writer-director Robbins does make the character of Welles (Angus MacFadyen) a silly boozer and pretentious loudmouth without a serious bone in his body — something closer to Jack Buchanan’s loose parody of Welles in the 1953 MGM musical The Band Wagon than a historically responsible depiction of Welles in 1937. Yet Welles is a marginal character in Cradle Will Rock, and he had little to do with its subject, the short-lived glory of American socialist art. Furthermore, the film’s depiction of that subject is both historically defensible and rather gutsy.

The heroes of Robbins’s movie are Hallie Flanagan (Cherry Jones), head of the WPA’s Federal Theater, who defended state-funded art against the stupid (and very 90s-like) attacks of Martin Dies and his House committee; and Aldo Silvano (John Turturro), a populist everyman and somewhat fictionalized Italian-American cast member of Marc Blitzstein’s Marxist opera, The Cradle Will Rock, perhaps suggested by Howard da Silva, who opposed the sliding of his home country toward fascism. Welles, rightly, isn’t much more than an irritating speck in relation to these two noble presences. (More questionable is Robbins’s letting Dies be a more coherent and dignified character than Welles, though this suits his ultimate strategy.)

In 1937 Welles was a 22-year-old radio actor who was extremely well paid but usually unbilled; he was just starting to make a name for himself as an innovative theater director who sometimes acted in his own productions, but he hadn’t yet become a radio or film director. No matter how highly one ranks Welles as an artist — or as a “premature antifascist,” who spoke at a Communist bookshop, wrote for the Daily Worker, and emceed a benefit concert for New Masses in 1938 — his importance in the history of socialist art is marginal at best. The same could be said of Welles’s producer John Houseman (played by Cary Elwes as an improbable blend of Tom Wolfe and William Buckley). Robbins is generally more respectful of Diego Rivera as a leftist artist of this period, but even Rivera, as played by Ruben Blades, comes across like a cartoon radical; Hank Azaria’s Blitzstein registers somewhat like an effete version of John Waters or Billy De Wolfe, a light comic actor in 50s musicals.

Only Rivera’s and Blitzstein’s art are accorded any real integrity; the artists themselves are not, perhaps because Robbins hates elitism and star politics — one reason he may distrust Welles. If Robbins had more imagination and more capacity for nuance he might have appreciated the irony of Welles’s hefty salary as an anonymous radio actor being fed directly — albeit secretly and illegally — into his Federal Theater productions, making those productions, like all of his movies, unclassifiable hybrids of public art and private enterprise. But then Robbins already had a pretty complex story about art, politics, and patronage — one that doesn’t betray the significance of the spontaneous populist premiere of Blitzstein’s opera after the government shut it down. This premiere was essentially without a director or sets, and it brought more fame to Welles (who’d directed the production that was shut down) than Welles brought to it.

Welles fully recognized this paradox in his [screenplay] . . . — a script Robbins says he deliberately didn’t read before writing his own. . . . Perhaps because [this] script, unlike Robbins’s, is built on personal recollections, its nostalgia for the period registers quite differently: it’s the reverse of [Robbins’s] in its warm treatment of individuals and its relative indifference to collective expression. Robbins gives the dated Blitzstein opera much more attention, plainly seeing it as the last hurrah of American collectivist art, and to build his case he takes a few pretty dubious historical shortcuts — such as making Nelson Rockefeller the godfather of American abstract painting. Yet regardless of his movie’s faults, Robbins’s real point is to show us what we lost when we abandoned socialist art rather than what we gained, and that’s an affecting and meaningful story. If Welles gets lost in the shuffle, you can’t have everything.

P.S. There’s an interesting and thoughtful critique of both the Welles screenplay and the Robbins film in an article by Joseph McBride published in Reel (March/April 2000) — unfortunately not available online, although some elements from it reappear in his subsequent book, What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career. — J.R.

It somehow seems fitting that in order to piece together Orson Welles’s autobiography, we have to turn to his creative work. The unceasing desire and energy to produce that coursed through the seventy years of his life, and literally kept him occupied until his final moments, crowded out the opportunity to recount his life in tranquility, at least in any complete form, yielding only a series of tantalizing fragments. There’s a moving account in F for Fake (1973) of how, in Dublin at the age of sixteen, he launched his professional career as an actor, and Filming Othello (1979) describes how, in Morocco in his mid-thirties, he launched his career as an independent — as opposed to studio — filmmaker. A series of extended interviews with Peter Bogdanovich in the late 60s and early 70s — This Is Orson Welles (HarperCollins, 1992) — fill in some other parts of his life story, and a film project he worked on intermittently over the last decade in his life, Orson Welles Solo — a sort of scrapbook self-portrait for which he filmed conversations with his old friends Roger and Hortense Hill in 1978, and wrote two brief autobiographical fragments about his parents, “My Father Wore Black Spats” and “A Brief Career as a Musical Prodigy” (both published in the Christmas 1982 issue of the French Vogue) — fill in a few more. Very shortly before his death, he began writingan autobiography in earnest, but never got beyond a few pages.

Perhaps the most extended and complete of his autobiographical ventures was written in 1984, the year before his death, and it came about quite by chance. If, as Welles often pointed out, a film director is someone who “presides over accidents,” the “accident” that brought about this protracted exercise in self-scrutiny — an original screenplay called The Cradle Will Rock — is no less striking than the series of chance occurrences charted in the script itself.

Producer Michael Fitzgerald, whose features at this point included two John Huston pictures, Wise Blood and Under the Volcano, had commissioned a first-draft screenplay from Ring Lardner, Jr., Rocking the Cradle, which dealt with the events surrounding Welles’s 1937 stage production of Marc Blitzstein’s “play with music,” The Cradle Will Rock. Fitzgerald then showed this script to Welles in June 1984 for his approval, and over the course of their ensuing discussions, invited Welles to direct the film himself. After showing some initial reluctance about the project (see Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles for details), Welles wound up not only agreeing, but completely discarding Lardner’s script and writing a new one himself — turning the film in the process into an autobiographical account of his life during the first half of 1937, just before and after he turned twenty-two. (In Lardner’s script, Welles was a less central figure — certainly a less developed one — and the emphasis was placed more squarely and exclusively on the production of the Blitzstein play.)

Insofar as this period constituted the time just before Welles achieved his biggest fame — he appeared on the cover of Time magazine on May 6, 1938, less than a year after The Cradle Will Rock opened — the script can be said to describe an existential point in his career that may have been even more decisive than any of his subsequent adventures in Hollywood, Latin America, or Europe. Indeed, precisely because this pivotal moment is virtually lost today to those who assume that Welles’s career “began” with Caesar on the stage (November 11, 1937), The War of the Worlds on radio (October 30, 1938), and/or Citizen Kane in film (May 1, 1941),

Welles’s focusing on it here carries the force of a resurrection — the summoning up of a forgotten past that implicitly affects our sense of everything that came afterward. Following on the heels of another original screenplay by Welles, The Big Brass Ring — written in 1981–82, and published posthumously by Santa Teresa Press in 1987 — The Cradle Will Rock might be said to bear some of the same relationship to its predecessor as The Magnificent Ambersons has to Citizen Kane: after a flamboyant and fearless speculation about corruption, a modest and highly self- critical reflection on the brashness of innocence, tinged with sweetness and nostalgia.

Significantly, The Cradle Will Rock was by far the most “directorless” of Welles’s stage productions, and in order to ferret out the overall meaning it had in a career that is known mainly for its individuality, it becomes necessary to arrive at an understanding of the overall political and social context in which Welles flourished during the late Depression. As Michael Denning has argued in an essay that has direct bearing on this issue, “If the Mercury project is representative of the popular front, their productions may be read as allegories of their contradictory populism, a populism worth reexamining in the midst of our own debates over the politics of that contemporary embrace of the popular which has been called postmodernism.” (1)

For Denning, the premiere of The Cradle Will Rock constituted the first of two events “that prevented the Mercury from becoming merely an avant-garde theater group, from being a radicalism of special effects” — the other event being “the panic caused by the radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds” the following year. “The evening [of the Cradle premiere] marked the end of Welles’s and Houseman’s connection to the Federal Theatre; and its notoriety launched the Mercury Theatre that fall. And it served as an emblem of what Houseman and Welles meant as a people’s theater, which was less an ideological theater — though despite Houseman’s latter-day disclaimers, they shared what Gramsci would call the ‘common sense’ of the popular front—than a theater marked by a new and wider audience.” As Blitzstein himself noted at the time, in a piece written for the Daily Worker, “ The Cradle Will Rock is about unions, but only incidentally about unions. What I really wanted to talk about was the middle class.” For all its trappings as a proletarian labor opera, The Cradle, which Blitzstein dedicated to Bertolt Brecht, was specifically conceived as a Marxist work that addressed itself to the bourgeoisie.

Furthermore, if we agree with Denning that ultimately, the “Mercury went from an experiment in people’s theater to a trademark for a star,” the brief period covered in the Cradle screenplay might be said to be the period when the ambiguities of that contradictory evolution were most apparent — ambiguities that, judging from the screenplay, weren’t entirely lost on Welles himself. One thing, for example, that clearly distinguished the Welles-Houseman projects for the Federal Theater — and which serves to account for the fact that they succeeded in forging more productions through the WPA bureaucracy than all the other theater groups — was the fact that they illegally drew funds from Welles’s lucrative career during this period as an anonymous radio actor. (It could be argued, indeed, that part of the scandal of Welles’s iconoclasm throughout much of his career — encompassing not only the period covered in Cradle, but such later maverick film productions as Othello, Don Quixote, and The Deep — was his willingness to subsidize substantial portions of his own work.) Such details as the political ambivalences of Orson and Virginia about their upper-class habits and attitudes [see still below], Orson’s reference to his uncollected WPA salary (which was actually $23.86), and his changing an effect in Dr. Faustus with the use of a mirror in order to make room for Blitzstein’s rehearsal piano, should all be seen in light of the particular conflicts and negotiations provoked by The Cradle between Welles’s political and entrepreneurial drives.

For conceptual insights into what sort of film Welles wanted to make from his script, Welles’s young friend Jim Steinmeyer — a magician he met in the early 80s, saw on the average of once a week and discussed The Cradle Will Rock with at length — has been especially helpful. About a year and a half prior to the Cradle script, Welles had already discussed with Steinmeyer a possible film project about magic shows at the turn of the century, and their common interest in magic proved to have more relevance to certain aspects of Cradle than might first seem apparent. As Steinmeyer put it to me, Welles wanted to present himself in the film as a magician on Broadway.

Take, for instance, the backstage and behind-the-scenes basement glimpses of Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus that are witnessed by Marc Blitzstein towards the beginning. Welles recalled Dr. Faustus to Steinmeyer as an “all black-art show,” a production whose magical effects were centered on lights and curtains. Discussing with Steinmeyer the relationship between events on the stage and events under the stage, Welles wanted to convey the impression that the under the-stage operations “explained” the onstage magic without its actually doing so. He didn’t feel, moreover, that he had to represent the original Faustus production faithfully. In the original, there was a scene featuring “The Seven Deadly Sins” that consisted of Bil Baird’s puppets and floating objects, including a pig, that were moved around invisibly by stagehands dressed in black. Although a pig played a minor role in this scene, it wasn’t a pig that was big enough for an actor to ride. For the very elaborate, “borderline impossible” floating pig trick in the movie — which Welles wanted to shoot in Rome for economic reasons, and which was designed and built by John Gaughan — a number of shifting principles were involved. Steinmeyer declined to go into further details about this (too many of the principles are currently in use by other magicians), but stressed that “black art” wasn’t involved: the trick would have been performed in bright light.

Steinmeyer recalls Welles saying that the script remained the most important aspect of the film to him; theoretically it could have been directed by someone else. The most important thing about the casting for him was getting actors who looked like the original people. (Some of the actors he contemplated using at various points were David Steinberg as Marc Blitzstein, Amy Irving as Virginia, Jackie Mason as Moishe the cab driver, and David Ogden Stiers as John Houseman; Stiers having studied with Houseman and observed him first-hand was a particular incentive.)

Entertaining some doubts about how Blitzstein’s Cradle might play for a contemporary audience, Welles lent an audiocassette of the opera to Steinmeyer; when his friend reported back that he didn’t like it much, Welles sadly agreed that the play was dated and said that he would endeavor (in Steinmeyer’s words) “to write circles around it.”

***

In the August 30 issue of Variety, Todd McCarthy reported that production manager Tom Shaw was “lining up locations and crew for a moderately budgeted production” that would require ten weeks of shooting, with nine weeks in Los Angeles for interiors and another week of second unit work in New York. John Landis and George Folsey, Jr. were slated as executive producers and Michael and Kathy Fitzgerald, assisted by Prince Alessandro Tasca di Cuto, were announced as “line” producers. Ted Pedas’s Circle Theaters — an eight-screen movie theater chain in the Washington, D.C. area — were cited as the source of financing, and McCarthy added that English actor Rupert Everett was cast in the part of the young Welles.

According to Tasca, the initial budget was $6 million, and the shooting locations and facilities that had been pre-figured by the fall — while Welles worked on revising his script in October and November — included a still wider range of possibilities: one theater south of Long Beach and two theater interiors in Rome, Italy (one of them a cinema called the Olympico); exterior locations in Staten Island and Hoboken as well as downtown Los Angeles; possible studio work in Los Angeles (without union crews) and/or Utah; and studio work for the film’s country house interiors in Rome. The film would be shot on color negative (as a commercial safeguard) but processed in black and white.

But by the end of the year, the expected financing failed to materialize; and what began as a hopeful postponement eventually became a regretful cancellation a few months before Welles’s death on October 10, 1985 — even after the budget had been reduced to $3 million and various European investors had been sought. (Another story in Variety dated May 31, 1985, and filed from Munich reported that the film, now allegedly called Let the Cradle Rock, “may begin within a year’s time,” with Hans Brockmann of Anthea Films co-producing with Michael Fitzgerald, and shooting to take place entirely in Europe.)

When Welles, in one of his last-ditch efforts to save the project, invited Steven Spielberg and his then-wife Amy Irving (tentatively cast as Virginia Nicolson Welles) to lunch at Ma Maison, there might have still been some cause for hope. Spielberg, after all, had recently spent $55,000 at an auction for the Rosebud sled in Citizen Kane, and according to Welles biographer Frank Brady, Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom had even more recently grossed nearly $10 million in a single day. Perhaps Welles assumed that even if Spielberg didn’t want to invest in The Cradle Will Rock himself, he could lend a helping hand in other ways simply by picking up a phone; surely he had the clout to get someone to invest $5 or $6 million in what would have been the first Hollywood studio film by Welles in a quarter of a century, ever since Touch of Evil. But as Welles discovered to his regret, Spielberg didn’t even offer to pay for the lunch. (This story, incidentally, has been confirmed by Welles’s daughter Beatrice, to whom Welles recounted it later the same evening, in Las Vegas.)

Other friends or acquaintances in the industry were scarcely any more helpful. When Warren Beatty invited Welles to lunch at the same restaurant, asking him to bring the Cradle script with him, he insisted on reading the script straight through at the table while Welles sat waiting for him, then offered the suggestion that Welles shoot present-day interviews with surviving real-life participants in the original events — in short, imitate Beatty’s own procedure in Reds . . . . A couple of studio reports that I’ve read on the Cradle script seem characteristic: both readers complain that the script assumes an interest in Welles’s early life that they didn’t happen to share.

***

Far from anything like a settling of old accounts — a frequent motivation for showbiz autobiographies — Welles’s look back at his own youth is full of generosity towards others and more than a few skeptical notions about his earlier self, including his marital infidelities and his sexual double standard. Significantly, Virginia Nicolson both read and approved the screenplay during the preproduction, and even Welles’s old enemy John Houseman — who read it after Welles’s death and not long before his own — commented favorably on its overall fairness and accuracy.

It should be stressed, however, that Welles felt free to adopt a certain poetic license when it came to handling a few specific historical events, as well as some personal ones. A more precise chronology reveals some of the alterations:

Spring 1936: Blitzstein writes The Cradle Will Rock.

Fall 1936: Blitzstein meets Welles backstage during the run of the latter’s production of Horse Eats Hat to discuss Welles directing The Cradle for the Actor’s Repertory Company. (Soon afterwards, the project is put aside due to lack of funds.)

January 8, 1937: Dr. Faustus opens.

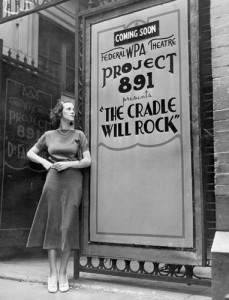

March 1937: Houseman and Welles decide to produce The Cradle at the Maxine Elliott Theater for Project #891 and rehearsals begin.

May 9, 1937: Dr. Faustus closes.

May 23, 1937: John D. Rockefeller dies.

May 30, 1937: Ten Republic Steel strikers are killed by the Chicago police.

June 1937: Technical rehearsals on The Cradle begin, despite massive budget cuts in the New York Theatre Project.

June 12, 1937: The production of The Cradle is prohibited by government order.

June 14, 1937: Final dress rehearsal for hundreds of invited guests.

June 15, 1937: A dozen uniformed guards take over the Maxine Elliott Theatre.

June 16, 1937: The play is performed at the Venice Theatre.

December 1938: Texas Representative Martin Dies asks Hallie Flanagan, head of the Federal Theatre, if “this Marlowe” is “a Communist.”

Not all of Welles’s characters in the script can be verified by other accounts of the period, so it seems possible that a few of them — including Solly Pruett, Moishe the cab driver, and Mayzie Katz, among others — are either fictionalized composites or pure inventions. (We have it on good authority, however, that Mrs. J. Sargeant Cram “really existed,” as Welles’s narration insists.) There’s also a likely telescoping of some of Welles’s future interests in Hollywood and presidential politics in the final dialogue with Virginia.

Perhaps the most telling calculated departure from history in the script is the name of the theater where the Cradle premiered, which was actually called the Venice rather than the Seville. (Subsequently, the same theater was renamed the New Century, then the 57th Street.) In fact, Welles gravitated between calling the theater the Venice and the Seville in separate drafts of the script; Tasca has a script dated November 1984 which calls the theater the Venice, but his call-sheet for the production lists it as the Seville. Like the question of whether Blake Pellerin or Kim Meneker murdered the blind beggar at the end of The Big Brass Ring, Welles’s uncertainty about this matter, probably based on his autobiographical associations with both cities, evidently carried some potency for him; as his companion and collaborator Oja Kodar pointed out to me when I brought this matter up, “Orson sometimes liked to invent his own superstitions.” (A line from movie director Jake Hannaford in the script of Welles’s still-unreleased The Other Side of the Wind : “Seville. That’s one of the great places. Venice, Ankorvat, the God-damned Pyramids — they’re all so many used-up movie sets.”)

Negotiating the complex truces between fiction and nonfiction is a daunting task throughout Welles’s work, largely because the Cradle screenplay is far from being the first time that he works with a fictional or non-fictional character named Orson Welles. Throughout his radio career, for instance, one finds him sharing the same narrative space as his fictional characters. In his radio version of Huckleberry Finn (broadcast on March 17, 1940), there are extended dialogues between “Huck Finn” (Jackie Cooper) and “Mr. Welles”; in his own controversial radio play His Honor the Mayor (broadcast on April 6, 1941), where he functions as narrator, he remarks at one point of his hero Bill Knaggs (Ray Collins), the mayor of a town near the Mexican border, “Believe me, I’m not campaigning for Knaggs’s re-election. He’s a friend of mine, but I don’t want to get mixed up in municipal politics, particularly in a town that’s almost 2,000 miles away from my own.” In 1944, on the variety show Orson Welles Almanac, there are even many times when he converses at length with the Disney character Jiminy Cricket.

After the triumphant premiere of Blitzstein’s Cradle, the show reopened at the Venice in the same impromptu form two days later, where it played through July 1st. During the same period, it was given an extra Sunday performance at an amusement park in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania and a performance in Uncasville, New York, before touring the steel districts of Pennsylvania and Ohio. On June 27, New York radio station WEVD — named after the socialist hero Eugene V. Debs — broadcast it. On December 5, the show was revived in a new “oratorio version” at the Mercury Theatre (formerly the Comedy Theatre, on 110 West 41st Street) on Sunday nights, utilizing the Caesar set, two rows of chairs, a reduced chorus of twelve, and Blitzstein himself resuming his original role at the piano. When Random House published the text of the play the following year, Welles began his Preface by saying, “I started producing Marc Blitzstein’s music drama the minute it was written almost two years ago, and I have been producing it almost incessantly ever since.”

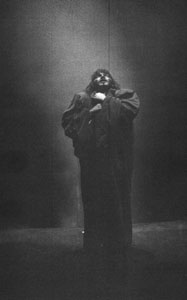

Welles and Blitzstein collaborated on many subsequent occasions over the next two decades, especially during the late 30s. Five months after the Cradle opened, Welles’s next stage production, Caesar [see above photo], featured music by Blitzstein; the composer performed the same role on Welles’s production of Danton’s Death a year later, and also did the music for the Mercury Text Records of Julius Caesar and Twelfth Night released in 1939. On February 8, 1938, Welles hosted a benefit concert for New Masses, during which Blitzstein’s half-hour “song play” I’ve Got the Tune, dedicated to Welles, received its stage premiere (with Count Basie performing in one section), and Welles arranged for the piece to be performed at the Mercury on two Sundays later the same month. In mid-July, Blitzstein played the part of a French barber in the film shot by Welles for his production of the stage farce Too Much Johnson [see still below]. Eight years later, when Blitzstein’s Airborne Symphony, a cantata for male voices, premiered at the New York City Center, Welles served as the narrator. And ten years after that, in 1956, again at the New York City Center, Blitzstein was in charge of the music for Welles’s last American stage production, King Lear, and played the harpsichord during its run. (2)

Indeed, considering the symbiotic and reciprocal nature of this friendship over the years, it might not be too fanciful to consider Blitzstein’s character as a sort of alter-ego of Welles in the script. (In this respect, Welles as scriptwriter may have been only returning the compliment. Welles was originally cast by Blitzstein as the composer, Mr. Musiker, in the autobiographical I’ve Got the Tune for its CBS radio premiere in October 1937, and Blitzstein wound up taking over the part himself only after Welles proved to be too busy rehearsing Caesar. ) For all the political differences between these characters, one could argue that Blitzstein not only influenced Welles, but eventually, in certain respects, came to stand for a significant part of his artistic persona — his political conscience and consciousness — over the remainder of his career.

In “The Director as Actor,” a paper delivered by James Naremore at a Welles conference in Venice, Italy in October 1991, there is a passage that pinpoints precisely the dual artistic persona that I have in mind:

. . . I would argue that Welles’s major accomplishment as both an actor and director was his ability to synthesize two apparently contradictory forms of theatricality: On the one hand, he was a brilliant practitioner of what John Houseman called “magical effect,” and he was clearly indebted to a romantic or gothic tradition of Shakespearian drama, grand opera, and stage illusionism; on the other hand, he was also a didactic, somewhat Brechtian storyteller whose cultural politics were shaped during the period of the Popular Front, and whose technique was visibly rhetorical, strongly dependent on direct address. The tension between these extremes — in other words, the tension between Welles as conjurer and Welles as narrator— accounts for many of the special qualities of his films in general.

Naremore goes on to cite F for Fake — where Welles “appears as a narrator-magician, and where he behaves like a cross between a pedagogue and a con man”—as a prime example of this duality. Very much the same duality is present at the first meeting between Blitzstein and Welles — a Brechtian pedagogue and a magician on Broadway — in The Cradle Will Rock, defining a kind of friendly ideological tension that continues throughout the script. A similar friendship of symbiotic opposites is defined between Welles and Jack Carter, and it’s worth adding that Welles actually did replace Carter in black face in the voodoo Macbeth during at least part of its run in Indianapolis in 1936. But if Carter literally played Mephistophilis to Welles’s Faust, and if, according to Houseman, Welles himself was also Mephistophilis to his own Faust, it’s less certain in the friendship between Welles and Blitzstein precisely who was Faust and who was Mephistophilis. Each clearly inspired the other to do things he never would have undertaken otherwise, and this screenplay shines with the fond memory of what happened when their mutual inspiration took the world by storm.

Notes

1. “Towards a People’s Theater: The Cultural Politics of the Mercury Theatre,” Persistence of Vision no. 7, 1989.

2. See Eric A. Gordon’s biography Mark the Music: The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), for a comprehensive account of Blitzstein’s career.