My column for the March 2020 issue of Caimán Cuadernoas de Cine… — J.R.

Greasing the wheels of commerce is usually the chief reason for end-of-the-year movie polls, which, like the Academy Awards, only intensifies our ongoing cultural confusion of film criticism with advertising. This helps to explain why (and how) Harvey Weinstein became Janet Maslin’s favourite film critic in her 1999 Cannes coverage for the New York Times, devoting far more space to his (negative) opinions about the prizes than anyone else’s, including the jury’s. (The fact that his own films in the festival hadn’t won prizes was of course crucial.) Perhaps because the head of that jury was David Cronenberg, an intellectual, the need for anti-intellectual cultural arbiters to drown out such controversial choices was as pressing two decades ago as it is today. We all need to be told not once, but repeatedly, why Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is more important to the state of our civilization, our lives, our senses, and even our ethics than Vitalina Varela, and whereas this sort of gatekeeping function was once reserved for the Times and its consumerist equivalents, today its counterparts have included, among others, Sight and Sound, Film Comment, the New York Review of Books, the London Review of Books, Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, and, alas, even Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 9, 1987). 2018: Criterion has a delightful digital edition of this.– J.R.

The nice thing about Rob Reiner’s friendly fairy tale adventure, with a script by William Goldman adapting his own novel, is how delicately it works in irony about its brand of make-believe without ever undermining the effectiveness of the fantasy. The framing device is a grandfather (Peter Falk) reading a favorite book aloud to his skeptical grandson (Fred Savage), and it’s the latter’s initial recalcitrance that the movie uses both as a challenge and as a safety net. In the imaginary kingdom of Florin, the beautiful Buttercup (Robin Wright) gets separated from the farmhand whom she loves (Cary Elwes) and betrothed to the evil Prince Humperdinck (Chris Sarandon), until the nefarious Vizzini (Wallace Shawn) sprints her away. The colorful characters and adventures that ensue are, at their best, like live-action equivalents to some of the Disney animated features, with lots of other fond Hollywood memories thrown in: Andre the Giant is like a cross between Andy Devine and Lumpjaw the Bear, while Mandy Patinkin’s engaging Inigo Montoya conjures up Gene Kelly in The Pirate. Every character, in fact, is something of a goofball, and while the film is inexplicably saddled with a PG rating, it delightfully cuts across age barriers to keep everyone charmed. Read more

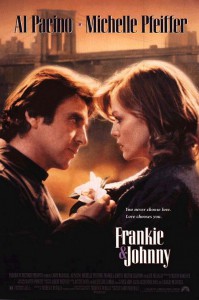

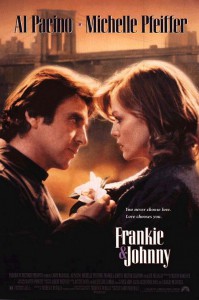

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1991). — J.R.

Terrence McNally’s two-character play Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune is about an embittered coffee shop waitress, the victim of rape by her father, who reluctantly succumbs to the advances of a much younger short-order cook fresh out of prison. Leave it to producer-director Garry Marshall, who brought us Pretty Woman, to Hollywoodize this grim scenario to the point of incoherence (with a script by McNally himself), casting Michelle Pfeiffer as the waitress and Al Pacino as the (now older) short-order cook, and substituting wife-beating for incestuous rape. To their credit, the filmmakers do a fair job of depicting the workings of a Manhattan coffee shop (despite some unnecessary cruelty involving one of the other waitresses), but not even the usually resourceful leads can overcome the missing or muddled motivations when it comes to the romance. Marshall only makes things worse by socking us with protracted, meaningful close-ups and punchy Marvin Hamlisch music meant to paper over the gaps. With Hector Elizondo (quite effective) and Kate Nelligan (painfully miscast) (1991). (JR) Read more