This article began as a lecture delivered on April 1, 2001 at the conference “Women and Iranian Cinema,” held at the University of Virginia and organized by Richard Herskowitz and Farzaneh Milani. Two years later it appeared in French translation in Cinéma/06, then in a booklet accompanying Facets Video’s DVD release of The House is Black in 2005, and it has also appeared in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (University of Chicago Press, 2010). — J.R.

The Iranian New Wave is not one but many potential movements, each one with a somewhat different time frame and honor roll. Although I started hearing this term in the early 1990s, around the same time I first became acquainted with the films of Abbas Kiarostami, it only started kicking in for me as a genuine movement — that is, a discernible tendency in terms of social and political concern, poetics, and overall quality — towards the end of that decade.

Some commentators — including Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa — have plausibly cited Sohrab Shahid Saless’s A Simple Event (1973) (1) as a seminal work, and another key founding gesture, pointing to a quite different definition and history, would be Kiarostami’s Close-up (1990) (2). Other touchstones would include Ebrahim Golestan’s remarkable Brick and Mirror (1965), Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969), Massoud Kimiaï’s Gheyssar (1969), and Parviz Kimiavi’s The Mongols (1973). But I’d like to propose a lesser-known short film preceding all of these, Forugh Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (1962) — a 22-minute documentary about a leper colony outside Tabriz, the capital of Azerbaijan. For Mohsen Makhmalbaf, it is “the best Iranian film [to have] affected the contemporary Iranian cinema,” despite (or maybe because) of the fact that Farrokhzad “never went to a college to study cinema” (3). It is also, to the best of my knowledge, the first Iranian documentary made by a woman. It won a prize at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1963 and was also shown at the Pesaro Film Fesrival three years later. For me it is the greatest of all Iranian films, at least among the 60 or 70 that I’ve seen to date. More than any other Iranian film that comes to mind, it highlights the paradoxical and crucial fact that while Iranians continue to be among the most demonized people on the planet, Iranian cinema is becoming almost universally recognized as the most ethical, as well as the most humanist.

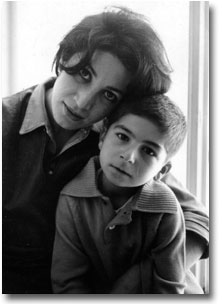

Farrokhzad (1935-67) — widely regarded as the greatest of all Iranian women poets and the greatest Iranian poet of the 20th century, who died in a car accident at 32 — made The House is Black, her only film, at 27, working over 12 days with a crew of three. The following year, in an interview, she “expressed deep personal satisfaction with the project insofar as she had been able to gain the lepers’ trust and become their friend while among them.” (4) I mainly want to consider it here for its anticipation of “the Iranian New Wave” as I know it. On a more personal level, Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and I worked with three others in subtitling The House is Black in English prior to its screening at the New York Film Festival in 1997, on the same program as Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry.

Though it was dismissed in a single sentence by the New York Times‘s reviewer, it clearly made a strong impression on many others who saw it there and in subsequent screenings at the annual Robert Flaherty Seminar and at Chicago’s Film Center, before the print was returned to the Swiss Cinémathèque. The same version is what is now being released by Facets Video, and though it doesn’t appear to be quite complete — one abrupt edit looks like a censor’s cut, and a few stray details visible in some other versions are missing — this is the best version of the film available in North America. (5)

A few relevant facts about the film: its producer, Ebrahim Golestan (born in 1922) — also a pioneering filmmaker in his own right, as I’ve already noted, as well as a novelist and translator (who translated, among other things, stories by Faulkner, Hemingway, and Chekhov into Persian) — was Farrokhzad’s friend and lover for the last eight years of her life, and she worked with him as a film editor before making her own film. (6) Her most notable editing job was on A Fire — an account of a 1958 oil well fire near Ahvaz that lasted over two months until an American fire-fighting crew managed to extinguish it. As Michael C. Hillmann accurately describes it, the film juxtaposes the fire with “the sun and moon, flocks of sheep, villagers eating, harvest time, and the like”.

Prior to working on A Fire in 1959, Farrokhzad studied film production as well as English during a visit to England. Shortly afterwards, she traveled to Khuzestan and worked on films there in several capacities — as actress, producer, assistant, and editor. (7)

According to Karim Emami, a writer and translator who worked for Golestan Films during this period, her first experience in handling a movie camera was shooting streets, oil wells, and petroleum pumps on a handheld super-8 camera in Agha-Jari, shooting from the interior of a touring car — an image that immediately calls to mind Kiarostami, Taste of Cherry in particular. She also appeared in the Iranian segments, filmed by Golestan, of an hour-long 1961 National Film Board of Canada TV production, Courtship — a discussion of the rites of betrothal in four separate countries — playing the sister of a working-class bridegroom in Tehran. She acted in another Golestan film that was never finished called The Sea, and another, in 1961, called Water and Heat or The View of Water and Fire. She also made one other film after The House is Black — “a short commercial for the classified ads page of Kayhan newspaper” which Emami regards as relatively inconsequential. (8) She is also said to have worked on still another Golestan film entitled Black and White, and plays an almost invisible cameo in his Brick and Mirror — the pivotal part of a young mother who abandons her infant.

In an interview last year, Kiarostami credited Golestan as the first Iranian filmmaker to use direct sound — a common attribution, I believe. But it’s worth noting that The House is Black, which clearly uses direct sound in spots, was made prior to Brick and Mirror, raising at least the possibility that Farrokhzad might have been a pioneer in this technique in Iranian cinema.

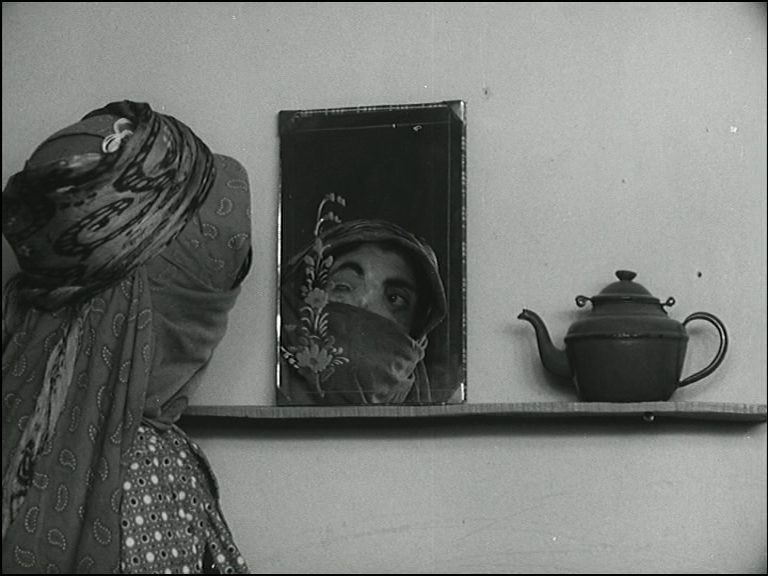

Defying the standard taboos and protocols concerning lepers — especially the injunction to avoid physical contact with them for her own safety — Forugh Farrokhzad wound up permanently adopting a boy in the colony named Hossein Mansouri, the son of two lepers, who appears in the film’s final classroom scene, taking him with her to Tehran to live at her mother’s house. Yet some of the film’s first viewers criticized it for exploiting the lepers — employing them as metaphors for Iranians under the shah, or more generally using them for her own purposes and interests rather than theirs.

When I first heard about the latter charge I was shocked, for much of the film’s primal force resides in what I would call its radical humanism, which goes beyond anything I can think of in western cinema. It would be fascinating as well as instructive to pair The House is Black with Tod Browning’s 1932 fiction feature Freaks — which oscillates between empathy and pity for its real-life cast of midgets, pinheads, Siamese twins, and a limbless “human worm,” among others, and feelings of disgust and horror that are no less pronounced. By contrast, Farrokhzad’s uncanny capacity to regard lepers without morbidity as both beautiful and ordinary, objects of love as well as intense identification, offers very different challenges, pointing to profoundly different spiritual and philosophical assumptions.

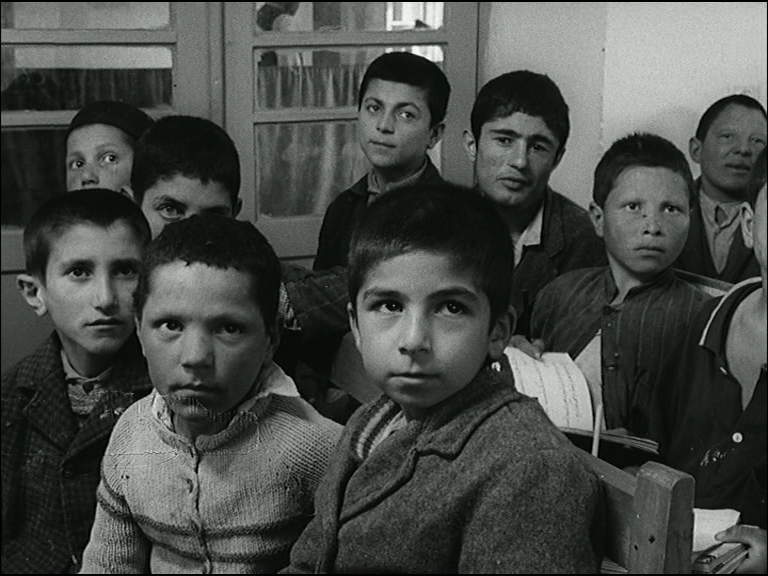

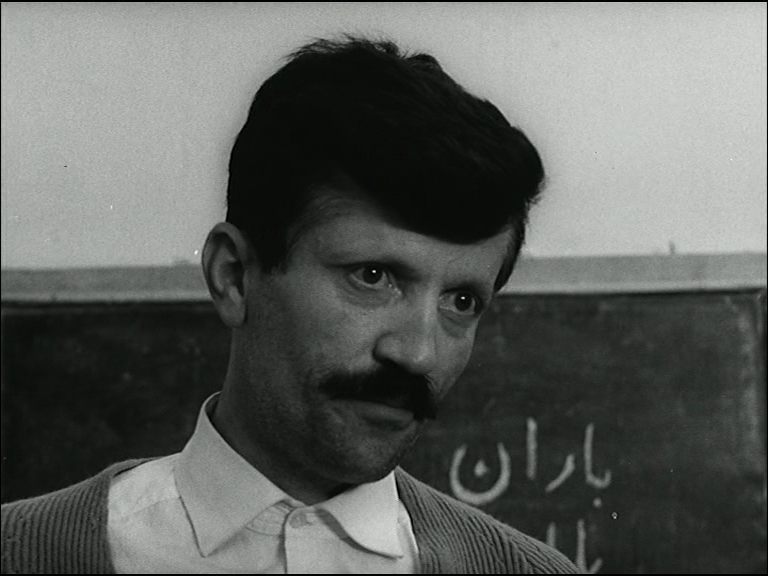

At the same time, any attentive reading of the film is obliged to conclude that certain parts of its “documentary realism” (perhaps most obviously, its closing scene in a classroom, as well as the powerful shot of the gates closing, which occurs just before the end)–working, like the subsequent films of the Iranian new wave, with nonprofessionals in relatively impoverished locations — must have been staged as well as scripted, created rather than simply found, conjuring up a potent blend of actuality and fiction that makes the two register as coterminous rather than as dialectical. (Much more dialectical, on the other hand, is the relation between the film’s two alternating narrators — an unidentified male voice, most likely Golestan’s, describing leprosy factually and relatively dispassionately, albeit with clear humanist assumptions, and Farrokhzad reciting her own poetry and passages from the Old Testament in a beautiful, dirgelike tone, halfway between multi-denominational prayer and blues lament.)

This kind of mixture is found equally throughout Kiarostami’s work, and raises comparable issues about the director’s manipulation of and control over his cast members. Yet without broaching the difficult question of authors’ intentions, it might also be maintained that the films of both Farrokhzad and Kiarostami propose inquiries into the ethics of middle-class artists filming poor people and are not simply or exclusively demonstrations of this practice. In Kiarostami’s case, it is often more obviously a critique of the filmmaker’s own distance and detachment from his subjects, but in Farrokhzad’s case, where the sense of personal commitment clearly runs deeper, the implication of an artist being unworthy of her subject is never entirely absent.

The most obvious parallel to The House is Black in Kiarostami’s career is his recent documentary feature ABC Africa (2001) about orphans of AIDS victims in Uganda — a film which goes even further than Farrokhzad in emphasizing the everyday joy of children at play in the midst of their apparent devastation, preferring to show us the victims’ pleasure over their suffering without in any way minimizing the gravity of their situation. (9) But it’s no less important to note that one of Farrokhzad’s poems is recited in toto during the most important sequence of Kiarostami’s most ambitious feature to date, whose title is the same as the poem’s, The Wind Will Carry Us (2000).

The importance of Farrokhzad in Iranian life and culture — where even today, and in spite of the continuing scandal that she embodies and represents, she’s commonly and affectionately referred to by her first name — points to the special status of poetry in Iran, which might even be said to compete with Islam. The House is Black is to my mind one of the very few successful fusions of literary poetry with film poetry — a blend that commonly invites the worst forms of self-consciousness and pretentiousness — and arguably this linkage of cinema with literature is a fundamental trait underlying much of the Iranian new wave.

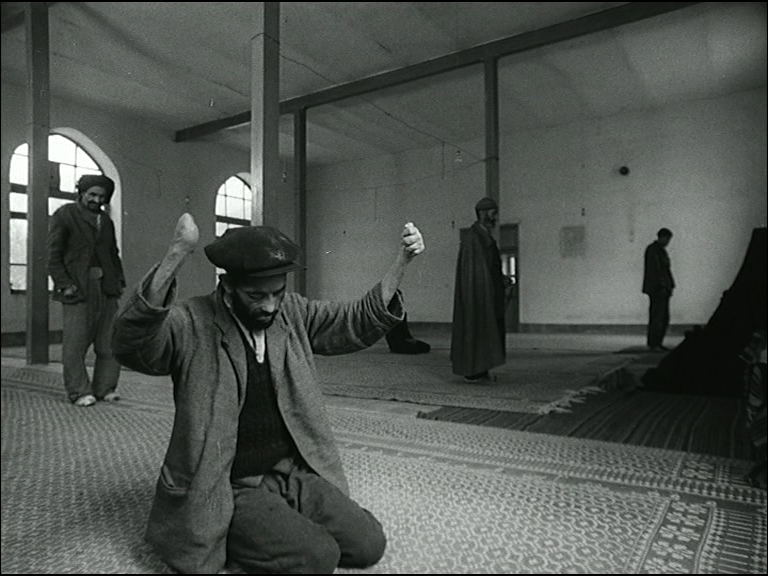

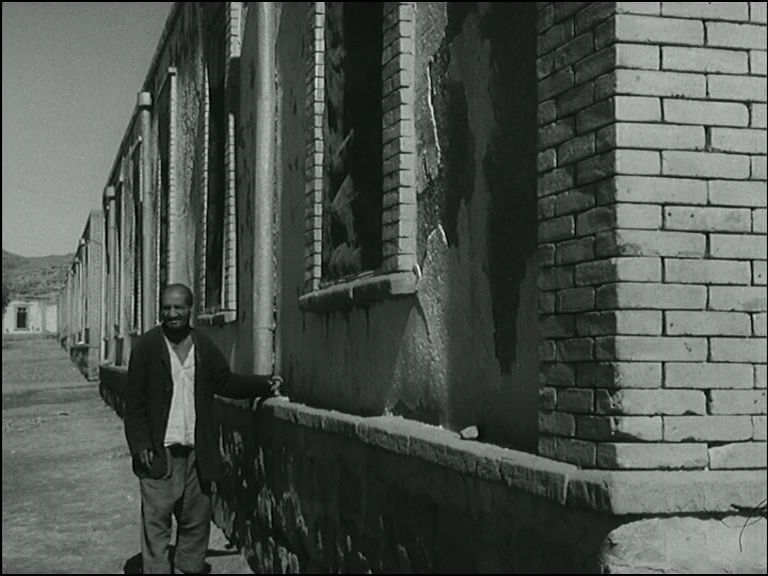

I hasten to add that “film poetry” is one of the most imprecise terms in film aesthetics, whether it’s used to describe Alexander Dovzhenko or Jacques Tati, so a few precisions are in order about why I’m using this term here. Much of what I have in mind is the suspension — or extension — of what we usually mean by “narrative” or “story” so that a certain kind of descriptive presence supersedes any conventional notion of an event. After a leper is seen walking outside beside a wall, pacing back and forth, intermittently hitting the wall lightly with his fingers, we hear Forugh very faintly offscreen reciting the days of the week over this image, the rhythm of her voice sounding a kind of duet with the man’s repeated gesture. Two notions of time are being superimposed here so that they become impossible to separate: an event lasting a few seconds and a duration stretching over days (and, by implication, weeks, months, and years).

Similarly, in the film’s penultimate sequence, while a one-legged man limps on crutches between two rows of trees towards the camera, we hear Forugh’s voice evoke a cluster of other images, some of them with very different time frames, over this single movement: “Alas, for the day is fading,/the evening shadows are stretching./Our being, like a cage full of birds,/is filled with moans of captivity./And none among us knows how long/he will last./The harvest season passed,/the summer season came to an end,/and we did not find deliverance./Like doves we cry for justice…/and there is none./We wait for light/and darkness reigns.” Again there is a kind of duet, ending this time in a kind of rhyme effect as her last two lines give way to the loud, clumping sound of the man’s footsteps in the foreground as his dark body directly approaches the camera, dramatically blotting out everything else.

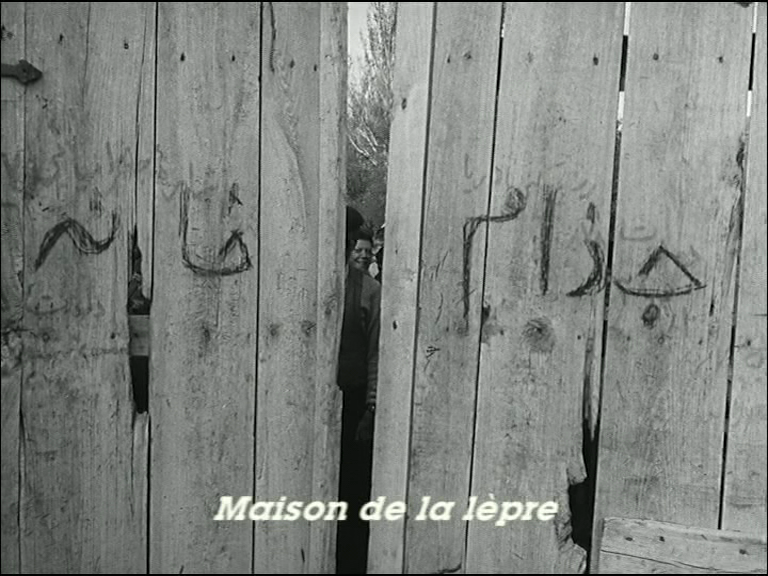

Although the film is mainly framed by two scenes in a classroom, the second of these is briefly interrupted by what can only be called a poetic intrusion — a shot I’ve already mentioned that is unrelated in narrative terms but enormously powerful in descriptive terms: a crowd of lepers is suddenly seen outdoors, approaching the camera, only to be blocked from us when a gate abruptly closes on them, bearing the words “leper colony” (or more precisely “leper house,” tied more directly to the film’s title). In narrative terms, this shot has no relation to what precedes and follows it apart from the most obvious thematic connection: lepers. Yet it functions almost exactly like a line in a poem –parenthetically yet dramatically introducing the brutality of our social definition of lepers and how it shuts them away from us — before returning us to the classroom.

That Farrokhzad was the first woman in Persian literature to write about her sexual desire, and that her own volatile and crisis-ridden life (including her sex life) was as central to her legend as her poetry, helps to explain her potency as a political figure who was reviled in the press as a whore and placed outside most official literary canons while still being worshipped as both a goddess and a martyr. Despite her enormous differences (above all, in gender and sexual orientation) from Pier Paolo Pasolini, it probably wouldn’t be too outlandish to see her as a somewhat comparable figure in staging heroic and dangerous shotgun marriages between eros and religion, poetry and politics, poverty and privilege — and a figure whose violent death has been the focus of comparable mythic speculations. She and her film remain crucial reference points because of their enormous value as limit cases, as well as artistic models. And as far as I’m concerned, if the Iranian New Wave begins with The House is Black, there’s no imagining where it can still lead us.

Notes

1. See “Sohrab Shahid Saless: A Cinema of Exile” by Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, in Life and Art: The New Iranian Cinema, edited by Rose Issa and Sheila Whitaker, London: National Film Theatre, 1999, pp. 135-144.

2. See “Confessions of a Sin-ephile: Close-Up” by Godfrey Cheshire, in Cinema Scope (Toronto), Winter 2000, issue 2, 3-8.

3. “Makhmalbaf Film House” by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, translated by Babak Mozaffari, in The Day I Became a Woman (bilingual edition of screenplay), Tehran: Rowzaneh Kar, 2000, 5.

4. Michael C. Hillmann, A Lonely Woman: Forugh Farrokhzad and Her Poetry, Washington, DC: Three Continents Press/Mage Publishers, 1987, 43.

5. A still better version — with French subtitles, taken mainly from the print shown in Oberhausen, and authorized by producer Ebrahim Golestan — was issued on DVD along with A Fire as part of the [then] biannual French magazine Cinéma (#07, printemps 2004) edited by Bernard Eisenschitz and published by Editions Léo Scheer. (This is the source of the frame reproductions used here with this essay.)

6. See also “Ebrahim Golestan: Treasure of Pre-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema” by Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, Rouge #11, 2007 (www.rouge.com.au/11/golestan.html).(2009)

7. Michael C Hillmann, op. cit., 42-43.

8. Karim Emami, “Recollections and Afterthoughts” (undated lecture delivered in Austin, Texas), quoted on Forugh Farrokhzad website, www.forughfarrokhzad.org (unfortunately no longer available at this address).

9. See also Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003, 37-40, 83-84, 119-123.

— Cinéma/06 (France), automne 2003; developed from a lecture delivered on April 1, 2001 at the conference “Women and Iranian Cinema,” held at the University of Virginia and organized by Richard Herskowitz and Farzaneh Milani; also published as essay in booklet accompanying DVD issued by Facets Video (U.S.) in 2005; see also www.jonathanrosenbaum.com/?p=8338.