From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976. — J.R.

Prividenie, Kotoroe ne Vozvrashchaetsya

(The Ghost that Never Returns)

U.S.S.R., 1929

Director: Abram Room

In an unidentified South American country, José Real is serving a life sentence for having led an oilfield workers’ strike ten years earlier. After another prisoner breaks away from guards to tell him that the prison governor has a letter from his wife, and then leaps to his death, Real leads a revolt among the prisoners. The governor orders that they be sprayed with hoses; the revolt subsides, and Real is locked into a narrow cupboard. Conferring with the chief of the secret service, the governor recalls the regulation whereby a prisoner who has served ten years is entitled to one day’s liberty and decides to grant this to Real, with the understanding that he will be killed at the day’s end for trying to ‘escape’. After being shown his wife’s letter and hearing from a newly arrived prisoner that a new strike is planned at Hillside Well, Real agrees to go. Five days later – after news of his imminent arrival has reached his family, their neighbors and the oilfield workers — he sets out, warned that no one who has taken this leave has ever made it back alive. On the train, he converses with and is offered food by a man who later proves to be an agent; falling asleep, he misses his stop and his wife searches for him in vain. Waking in the morning, he leaps from the train and the agent follows him through the desert as he enjoys his freedom; after he falls asleep again on a boulder, the agent wakes him to announce that he has only two hours left. With the agent still at his heels, he rushes to his house, which he initially finds empty. His father and his son appear, along with a friend who brings him to Hillside Inn to help organize a strike. When the agent and police arrive and Real declares that he won’t return, a fight between police and workers breaks out. Real rushes home to procure a gun from his wife and hurries out again. When sixty-five strikers are brought to the prison, the other prisoners learn that Real is leading the strike.

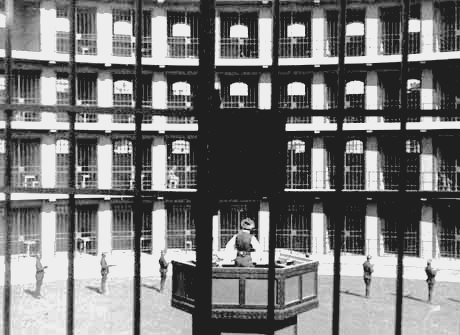

Considering the fact that it appeared in the same year as L’Argent, Blackmail, Un Chien Andalou, Hallelujah, Lonesome, Pandora’s Box, The River, Arsenal, The General Line, Man with a Movie Camera and The New Babylon –– the last four in the U.S.S.R. alone — The Ghost that Never Returns cannot be seriously regarded as a major film of its time. Clearly this was the opinion of the anonymous Bioscope reviewer who wrote of an allegedly re-cut version that surfaced in England in 1931: “Dreary story of man’s imprisonment . . . Incredibly slow development and poor continuity”. ln 1976, one’s verdict is likely to be much less severe, and with reason; but it must be acknowledged that the film was made during a period when silent film language was achieving its richest palette of possibilities, and even minor works could draw upon a common fund of expressive options. Benefiting as well as suffering from this opportunity, Room’s film runs through a virtual panoply of styles as if to anthologize the work of his masters. It begins as rather stodgy and heavy-handed propaganda: in an unnamed South American oil republic, a modern prison is laid out to resemble a cross between a futurist dream and a garish political cartoon, with four tiers of cells towering over a rotating observation post like a set left over from Metropolis. The governor is a grotesque apelike creature, dwarfed by his own chair and palatial office, whose suppression of a revolt with water-hoses occasions a battery of fancy montage effects, mechanically executed. The world outside is a rather cockeyed blend of oilfield, wilderness, suburban neighborhood and Wild West saloon, all set in confusing proximity to one another. Yet once the essential ingredients of this terrain are established, and psychological shadings begin to emerge from the depersonalized agit-prop, the film takes on a rather affecting life of its own. There is a world of difference between the minuscule figures glimpsed scurrying beneath outsized towers and vats at the beginning and the subsequent view of José Real in extreme long shot, as he emerges from the prison into a courtyard and breaks into a festive dance. When images of his wife and father previously appear in his shadowy cell — specters which he alternately acknowledges and ignores — fluctuating intensities of light gracefully outline the flux of his thoughts in relation to them; and the progression of rapid cuts which follows — first between Real’s head and details in the cell (initially static, then contained in pans), finally between his head and his wrist, before a shot of him running to his cell door is repeated several times in succession — beautifully sketches the experience of his last hours of confinement in a form of ‘notation’ anticipating Resnais. And once outside the prison, the plot itself proceeds to bend into a more human shape, as though the fiImmakers were offering themselves (like Real) a stretch of ‘irresponsible’ freedom within the confines of their commitments. The touching facts that Real falls asleep on the train and misses his stop (an extraordinary shot reveals his mute proflle beside the window through which his wife can be glimpsed frantically searching for him on the crowded platform), and that even the villainous agent is shown gathering flowers in the desert, begin to open the film up, allowing it to breathe more naturally. (The ambivalent treatment of the agent recurs at Hillside Inn, where Room indulges in huge and protracted close-ups of the back of his fat neck after he has shown him rather sheepishly and pathetically gathering up a plateful of leftovers from the saloon customers to fill his bourgeois belly.)

Consequently, the film’s reversion to propaganda at the end is much more persuasive and stirring than at the beginning, if only because the characters have been allowed some semblance of life in between. But unfortunately, as Jay Leyda has implied, the film’s end is needlessly ambiguous and elliptical about the struggle Real enlists in and its consequences: the titles indicate a strike, the acquiring of guns suggests an armed revolt, while the event itself is kept resolutely off-screen; with generalized titles filling in the gaps, the overall effect is awkwardly truncated and abrupt. And elliptical passages elsewhere (when, for instance, ReaI falls asleep in the desert, and is subsequently wakened by the agent) leave one in much the same uncertain position as that of the Bioscope reviewer over whether these lapses are attributable to the print under review or to Room himself.

Published on 12 Apr 2013 in Notes, by jrosenbaum