Posted by DVD Beaver in October 2007; I’ve updated many of the links. — J.R.

As with science fiction, the focus of my previous article in this series, the definition of what constitutes a fantasy film is to some extent arbitrary. Not every account of The Tiger of Eschnapur would situate it within the realm of fantasy, though I’d argue that a sequence involving a spider’s web that’s woven in the entrance to a cave, and perhaps other details as well, warrant such a description. The some goes for Confessions of an Opium Eater and its sudden shifts into slow-motion; these are nominally justified as opium-induced perceptions, but when the hero suddenly falls from a building and does several rapid cartwheels in midair, it’s impossible to tell at which point the logic of dreams takes over. In other respects, accepting Eyes Wide Shut as a fantasy is more a matter of interpretation than a matter of pointing at any obvious genre elements. And of course the realm of horror, which overlaps with fantasy without necessarily becoming fantasy (as in the cases of The Seventh Victim, Psycho, and Peeping Tom, for instance), accounts for at least four of my selections—Vampyr, Night of the Demon, The Masque of the Red Death, and Martin.

Being a fantasy isn’t in itself a badge of honor. To my taste, Jesus Franco’s Count Dracula (1970), a clear fantasy, is literally unwatchable, and Pere Portabella’s experimental documentary about the shooting of this film, Cuadecuc–Vampir, made the same year, is not even remotely a fantasy, yet it’s far richer with a poetic, beautiful, and creepy sense of the uncanny.

Although I’ve managed to include something from every decade except the present one, starting with the 1930s, I’ve reluctantly bypassed silent cinema here, from the fantasies of Georges Méliès (countless examples) to those of F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu and Faust — though not the recently released Phantom, which isn’t a fantasy despite its seductive title). These examples are certainly worthy, but my (arbitrary) definition of a fantasy film on this occasion entails the creation of an imaginary aural world as well as the creation of an imaginary visual one. (Partly because of this, there’s a strong erotic element in my list — especially in the first half, not to mention Martin and Eyes Wide Shut.) And I’ve omitted some other sterling examples, including the 1940 Thief of Bagdad, the best Disney animated features, and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953), either because they aren’t neglected or because I’ve already dealt with them in other categories (such as when I classified The 5,000 Fingers as an eccentric musical). As for Babe: Pig in the City (George Miller, 1998), I’ve held back from selecting this overlooked gem, superior to the anything-but-neglected Babe (Chris Noonan, 1995), only because I don’t remember it better. And the same goes for Hayao Miyazaki’s exquisite Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), which I haven’t yet gotten around to seeing in a subtitled version.

Vampyr (Carl Dreyer, 1932). It’s central to Dreyer’s greatness that he had to reinvent cinema and film language on his own terms, as if they had never existed before his own features. This was never more true than on his first sound film, which defines the uncanny in terms of film style as well as its characters and settings, developing the already transgressive styles of editing and camera movement in The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer’s last silent picture) into something even more spatially disorienting.

For many years, prior to the advent of videos and DVDs, most of Dreyer’s oeuvre was achingly out of reach, especially in prints that did justice to the carnal assault of his sounds and images. Now that this situation has radically improved, the most conspicuous gap in our appreciation of his work is a decent version of Vampyr — in some respects his creepiest and most erotic film (as well as his only foray into fantasy and horror). What we now have on DVD is invariably something cobbled together out of the separate English, French, and German versions of the film that he prepared in Berlin (after shooting the film silently in France), so that the same characters sometimes shift languages without warning, and the visual quality is often equally inconsistent. By all accounts, the best surviving version of the film is Martin Koerber’s restoration of the German version, done for ARTE Television in 1999, which reportedly runs a reel longer than all other surviving versions, but this has yet to appear anywhere on DVD. Let’s hope someone at Criterion and/or Masters of Cinema is scheming to make this available. [2015: This is now available on a two-disc DVD box set from Criterion.]

The Man Who Could Work Miracles (Lothar Mendes, 1937). It seems that the H.G. Wells film that almost everyone has heard about is Things to Come (1936), a rather grandiose SF effort directed by William Cameron Menzies. But back in the 50s when there were still double features on a regular basis at some theaters, I caught Things to Come playing with another British movie adapted by Wells from his own work, made the following year —- a piece of very English whimsy that’s also a serious fable about the tyranny of desire, at once more modest and more cosmic than its predecessor. A mousy young haberdashery clerk named George McWhirter Fotheringay (Roland Young, better known as Topper) gets picked at random by some quarreling gods in the starry sky and, as an experiment, is given the capacity to perform miracles, with offering him any explanation why. (He can do just about anything in the physical world, but he can’t alter how people think and feel.) Much of what ensues is pretty funny, and made all the more appealing by a fine supporting cast that includes Ralph Richardson as blustery Colonel Winstanley, Joan Gardner as the hero’s coworker Ada (whom he can’t induce to fall in love with him), and even George Sanders in a bit part as one of the quarreling gods.

I Married a Witch (René Clair, 1942). After a prissy 17th century puritan (Fredric March) fingers Jennifer (Veronica Lake), a leggy blond witch who enticed him into a hayloft, she and her father (Cecil Kellaway) get burnt at the stake, vowing in revenge that all his descendents will have unhappy marriages. And so they do, until the present — when their smoky essences are freed from an oak tree and, once she’s back in human form, she sets about winning prissy gubernatorial candidate Wally Wooley (March again) away from his shrewish fiancée (Susan Hayward), contriving for him to rescue her own naked body from a burning hotel.

This is a grand entertainment that first won me over when I caught a revival at age six. For my money it has more of Clair’s wit and poetry than any of his other Hollywood pictures; and the fact that Preston Sturges served as Clair’s (uncredited) coproducer on this comedy and acquired Lake for it (fresh out of Sullivan’s Travels) seems telling, because it has a few noticeable Sturges touches. It was adapted by many hands from The Passionate Witch — a novel left unfinished by Thorne Smith (of Topper fame) when he died, and completed by Norman Matson. The same novel served as the basis for the popular TV series Bewitched and its less popular Nicole Kidman spin-off, but for me this much earlier version of the story comes a lot closer to getting it right. And there’s something audacious as well as magical about having Lake and Kellaway converse while they’re smoke inside adjacent bottles; thanks to her deep, husky offscreen voice, she contrives to conjure up a seductive feminine aura of water, vapor, air, smoke, and flesh, making me fantasize even as a first-grader about taking a dip in the Lake of Lady Veronica.

Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (Albert Lewin, 1951). Reading various reviews of Lee Server’s recent biography of Ava Gardner, I was shocked to find the movie that defined her apotheosis — surpassing even George Cukor’s neglected 1956 Bhowani Junction in its erotic splendor — dismissed without a second thought. (It’s her first film in color, and lusciously shot by Jack Cardiff — the cinematographer on The Red Shoes, Under Capricorn, and The Barefoot Contessa, a film clearly indebted to this one.) This dismissal could never have happened in France, where this masterpiece is available on DVD and rightly revered as a summit for producer-turned-auteur Albert Lewin (a kind of Val Lewton on his six singular features he made, but with the benefit of big budgets) and James Mason as well as Gardner. (To commemorate what it meant to him as an adolescent, Jean Eustache featured a lengthy clip from it in Mes Petits Amoureuses.)

In Susan Felleman’s lovely auteurist study of Lewin, Botticelli in Hollywood, she charts in detail the film’s Surrealist sources, ranging from Man Ray (a friend of Lewin’s) to Giorgio de Chirico, and I think it could even be argued that this movie is the supreme encounter between Surrealism and Hollywood. (By contrast, the dream sequence designed by Dali in Hitchcock’s Spellbound is fairly drab and pedestrian.) So maybe part of the discrepancy between continental and American responses to this film is simply a matter of having a cultural context for the film’s delirious and deliberate romantic excesses. The story is centered on two mythical archetypes–Pandora (Gardner), an American chanteuse in a small colony of expatriates in Esperanza, a village on Spain’s Costa Brava circa 1930, who lures men to their doom, and the Flying Dutchman (Mason), a mysterious and taciturn sea captain who arrives one day. Condemned many centuries ago for the murder of his innocent bride and for blasphemy, he’s obliged to sail alone in his ship for all eternity unless he finds a woman willing to die for him. (This film is almost precisely contemporary with Orson Welles’ Othello, and there’s an uncanny echo of a shot in which Othello approaches Desdemona in her bed, when we see Mason in a flashback approaching his own bride.)

Mademoiselle (Vincente Minnelli, 1953). People tend to forget nowadays that MGM was capable of making glossy art movies in the early 50s. A prime example is the star-studded The Story of Three Loves, containing three loosely connected 40-minute sketches —- each one a bittersweet parable about love and art, a compromise between American fantasies about Europe and continental émigré fantasies about the U.S., in which pop existentialism serves as the main bill of fare. (If you consider that 1953 was the year Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness came out in English, this was being pretty up to date.) The first and last episodes, both directed by Gottfried Reinhardt (son of legendary German stage director Max Reinhardt), are tales about a ballerina (Moira Shearer) with a heart condition dancing herself to death for a genius director (James Mason) and about two guilt-ridden victim-heroes (Kirk Douglas and Pier Angeli) in Paris who become a trapeze-artist couple suspensefully gambling on each other.

Mademoiselle, directed by Minnelli, is the inspired centerpiece and only fantasy. An 11-year-old American boy (Ricky Nelson) in Rome who seems modeled on Daisy Miller’s bratty kid brother hates his literary French governess (Leslie Caron), but then he falls in love with her after an obliging American witch in the same hotel (Ethel Barrymore) enables him to turn into Farley Granger for one enchanted, Cinderella-tense evening. Miklós Rósza wrote the lush music, and Minnelli’s magical feeling for dreamlike drifts is fully in place.

The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb (Fritz Lang, 1959). Lang’s return to his German roots —- belatedly filming a fairy-tale-like script that he and Thea von Harbou had written during the silent era (and that had been filmed, to his consternation, by Joe May rather than himself) —- never had much of a chance to register in the English-speaking world after the two features got dubbed, drastically reduced in length, and cut together into a single feature called Journey to the Lost City that was critically greeted with scorn. These opulent color films fared better with the public in Europe, though Lang himself, perhaps embarrassed by their unabashed directness, (in the lushness of their décor, the eroticism of Debra Paget’s dancing with a cobra, and the artificiality of certain effects (such as the cobra being moved about with wires), became somewhat dismissive of them. To accept their deliberately childlike and somewhat kitschy innocence may require a certain tolerance and trust on the part of the viewer, but this luscious celebration and exploration of Lang’s favorite tropes and themes fully repays the effort.

To the best of my knowledge, these movies premiered in North America in their original form only in 1981, when I programmed them as part of a “Buried Treasures” series at the Toronto Festival of Festivals, and outside of New York, they never had a proper commercial run anywhere. The ironic theme of my series was “bad movies” — by which I mainly meant great, beautiful, and awesome movies that had been misunderstood and thus considered bad at one time or another. (Other examples ranged from Leo McCarey’s An Affair to Remember to Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge to James B. Harris’s Some Call it Loving to Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky.) But sadly, the only film I considered truly bad, Edward D. Wood’s Glen or Glenda?, was the biggest hit of my series —- which seemed to suggest that beauty and greatness weren’t what people wanted most from movies. But if it’s what you’re looking for now, there are glorious versions available on DVD.

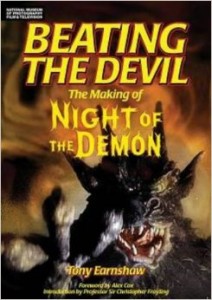

Night of the Demon (Jacques Tourneur, 1957). Shot in England, this is the best horror film Jacques Tourneur made after his stint in the 40s with Val Lewton which yielded Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Leopard Man. And since none of these films with the possible exception of the first really function as horror films, apart from their ads, Night of the Demon might well be his greatest horror film of all; it’s almost certainly the scariest. Neither Tourneur nor screenwriter Charles Bennett wanted the title demon to be seen, however, and bitterly complained when producer Hal E. Chester insisted on inserting a few glimpses of this beast. Like Clair above and Joe Dante below, among others, Tourneur considered the audience’s imagination one of his key artistic tools, and not allowing it to function as fully as it might was actually depriving him of something, not making any significant addition to his bag of tricks. (A good example of Tourneur using our imaginations is the sequence near the end where an unidentified hand in the foreground appears on a stair banister and is never explained or accounted for. This hand, incidentally, belonged to Tourneur himself.)

A fascinating, well-researched recent book about the making of this film (Tony Earnshaw’s Beating the Devil: The Making of Night of the Demon, Sheffield, England: Tomahawk Press, 2005) suggests that Chester, who brought in an old crony, blacklisted writer-director Cy Endfield, to do additional, uncredited work on the script, may have also gotten Endfield to direct the added shots of the demon, although the evidence supporting this is ambiguous. (For whatever it’s worth, Endfield —- whose masterpiece Zulu is the focus of an even more detailed and definitive book by the same publisher, also brought out last year — once told me he did a rewrite of the script that wasn’t used and thought he could have done a better job directing the script that was used than Tourneur, but said nothing about directing any part of it.)

Confessions of an Opium Eater (Albert Zugsmith, 1962). Is it excessive to include two Vincent Price opuses here? (See The Masque of the Red Death, below.) Maybe, but this truly bizarre Z-film, also known as Souls for Sale and Evils of Chinatown, is so off the map that it scarcely qualifies as an alternate version of anything — including the famous Thomas DeQuincey book, Confessions of an English Opium Eater, that this movie half-heartedly claims to be based on. As producer and/or director, Albert Zugsmith was responsible for some of the best and worst things to come out of Hollywood. (Among the best were The Incredible Shrinking Man, Touch of Evil, The Tarnished Angels, and this curiosity; among the worst were The Beat Generation and The Private Lives of Adam and Eve.) So it’s hard to know who or what to credit for the strangeness of this low-budget effort, which starts off like a tacky outdoor action thriller and becomes progressively more dreamlike and inscrutable as it proceeds into cramped interiors with its philosophizing dialogue, its hidden rooms and secret passageways, and its nearly all-Asian cast. The spirits of Louis Feuillade and Fritz Lang? Screenwriter and associate producer Robert Hill, whose other credits look pretty undistinguished? Art director Eugène Lourié, whose other films range from Rules of the Game to Shock Corridor? The eerie original, theremin-laden score by Albert Glasser (Teenage Cave Man)? The striking cinematography by Joseph F. Biroc (Forty Guns)? Or some happy chemistry arising from the encounter of some or all of these people with Zugsmith?

DeQuincey’s memoir was first published in 1822, then reappeared in an expanded edition in 1856. Price plays an obscurely motivated Gilbert DeQuincey, who may or may not be a descendent, explaining offscreen that about a hundred years after Thomas DeQuincey came to London in 1802, he came to San Francisco’s Chinatown during a Tong war. Kidnapped Chinese picture brides are about to be auctioned off, some of whom he befriends, but where he stands in relation to the warring factions is never entirely clear.

8. The Masque of the Red Death (Roger Corman, 1964). “If Poe had lived today he would probably have been a filmmaker,” writes Diane Johnson at the end of her Introduction to Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales. This is persuasive — even though it’s debatable whether Poe himself would have made this adaptation (by Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell) of his lushest apocalyptic tale. (Poe’s “Hop-Frog,” written seven years later, is also woven in as a subplot — an understandable addition, because the original “Masque” story consists of little more than seven pages of moody description, and most of the movie’s storyline doesn’t come from Poe at all.)

Nevertheless, this remains the most opulent and haunting of Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations, shot in Pathécolor and ‘Scope by Nicolas Roeg on some of the sets left over from Becket while creating a grimly coherent world of its own, albeit with a few glancing nods to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). We learn from Corman on the DVD that John F. Kennedy was assassinated and the Beatles had their first London premiere while this movie was being shot (lead actress Jane Asher was dating Paul McCartney at the time), and it’s a tribute to the film’s atmosphere that the 60s ambience isn’t always front and center, as it is with most Corman efforts of this period. (For a hippie version of the Middle Ages, check out John Huston’s neglected A Walk with Love and Death if you can find it, made five years later.) Vincent Price plays evil and decadent Prince Prospero, Asher the rebellious peasant he takes hostage, and Patrick Magee is also on hand for some lively pre-Kubrick mugging.

Martin (George A. Romero, 1977). Romeo’s second midnight-movie success after Night of the Living Dead was his fifth feature. It appeared around the same time as David Lynch’s much better-known Eraserhead, which may have muted its impact, and it lacks the stripped-down action and cascading gore of Romero’s other horror films. Yet as a kind of genial shotgun marriage between James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and Dracula, set in a Pittsburgh suburb called Braddock, it has a sweetness about being a lonely teenager that for me gives it a special place in Romero’s oeuvre. In our 1983 book Midnight Movies, J. Hoberman and I concluded, “it is the most technically proficient of all his hits and arguably his best film to date.” So it’s a pity that his fascinating and more obviously satirical quartet of Dead films has tended to overshadow this quieter chamber piece, a kind of low-key comedy.

John Amplas plays the eponymous hero, and whether he’s an actual vampire or a horny kid who imagines he’s one is a question the movie repeatedly raises without ever resolving. The continuity throughout between humdrum reality and fantasy us especially apparent whenever we hear Martin chatting as The Count on a late-night radio talkshow.

Innerspace (Joe Dante, 1987). Dante has on occasion cited this as his personal favorite, but many of his fans, myself included, have a tendency to overlook it, maybe because it lacks the sociopolitical edge that gives most of his best efforts a lot of their bite (Gremlins, Matinee, The Second Civil War, Small Soldiers, and Homecoming, for instance). It also takes a little while for this goofy comedy to get started —- that is, just over 26 minutes to arrive at the point where the central premise clicks into place. But then, for the remaining 94 minutes, it’s pretty clear sailing.

Much as the conceit of Veronica Lake and Cecil Kellaway in I Married a Witch (see above) being represented by smoke in a couple of bottles is a triumph of sound transforming image through the medium of our imaginations, Innerspace uses intercutting to convince us that a brash, miniaturized Navy pilot (Dennis Quaid) driving a sort of rocket ship accidentally gets injected into the bloodstream of a hypochondriac supermarket clerk (Martin Short) instead of a laboratory animal. Apart from some Oscar-winning visual effects which underline this curious state of affairs, this is basically a matter of showing us Short and Quaid in separate shots and asking our imaginations to fill in the rest, so that fantasy is essentially created in the mind of the beholder. This takes on more flavor and narrative complications once Quaid and Short find they can address one another and influence each other’s behavior and actions (such as when they romantically compete, after a fashion, for Meg Ryan). By the time various villains also get miniaturized or semi-miniaturized (including Kevin McCarthy and Fiona Lewis), the characters have essentially taken over the movie.

Eyes Wide Shut (Stanley Kubrick, 1999). I persist in regarding Arthur Schnitzler’s extraordinary Traumnovelle better than Kubrick’s long-contemplated adaptation, perhaps to the same degree that I prefer Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita to Kubrick’s. And I differ with Kubrick’s widow in considering Eyes Wide Shut the apotheosis of Kubrick’s career, even if he virtually completed it just before his death, insofar as I actually prefer Steven Spielberg’s realization of A.I. Artificial Intelligence. But none of this prevents me from cherishing Kubrick’s final feature -— regarding it as the most misunderstood masterpiece in his career, and therefore still awaiting a measured and reasonable assessment from much of the public.

To call the film a fantasy is only to half-understand it —- and to complain that its studio-built New York is “unconvincing” or that Sydney Pollack’s lengthy speech near the end “explains” too much is not to understand it at all. As the title itself suggests, this is fundamentally a film about fantasy — and not only the individual kind we entertain as individuals, but also the more collective kind we share with our relatives, friends, spouses, and significant others. From this point of view, virtually every scene and moment can be read in more than one way, because by design the precise divisions between reality and imagination in this picture are never precise. So we’re being asked to navigate our way through the story’s ambiguities to the same degree that the couple played by Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise is, and this is something we, like them, have to do both by ourselves and with others, comparing our own impressions as we proceed. As Gilles Deleuze once put it, most of Kubrick’s films are about brains breaking down. This happens in Eyes Wide Shut as well, but it might be said that here, for once, the brain is shared by two people —- and manages somehow to heal itself in the nick of time.