From the Chicago Reader (August 31, 1990). — J. R.

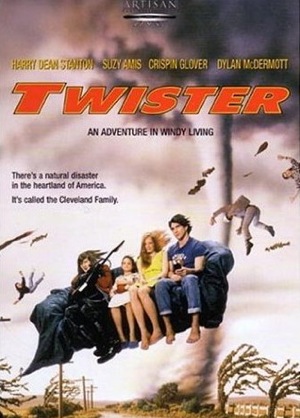

TWISTER

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Michael Almereyda

With Suzy Amis, Dylan McDermott, Crispin Glover, Harry Dean Stanton, Lindsay Christman, Charlaine Woodard, Lois Chiles, and Jenny Wright.

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The second part of the opening sentence of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina applies pretty well to the eccentric Kansas family in Michael Almereyda’s oddball comedy Twister, but in a way that’s only half the story. Not only is the family as a whole unhappy in its own particular way, most of its members are out of whack with themselves, each other, and everybody else too.

The father is Eugene Cleveland (Harry Dean Stanton), a distracted, long-divorced retired multimillionaire who made his fortune in soda pop and miniature-golf courses. His main distraction is courting Virginia (Lois Chiles), the born-again hostess of “Wonderbox,” a local Sunday-morning TV kiddie show that teaches toddlers about “the weather, animals, and God.” Maureen, or Mo (Suzy Amis), his 24-year-old chain-smoking alcoholic daughter, is a crabby recluse who hasn’t quite grown up or broken away from home; she occasionally camps out in the backyard of the family mansion, which borders a golf course. Violet (Lindsay Christman), her illegitimate eight-year-old daughter, seems relatively sane — as does Violet’s father Chris (Dylan McDermott), who has been in Canada for six months but returns as the film opens. Apart from the attention of Lola (Charlaine Woodard), a resourceful black maid who attends the local college, the child is somewhat neglected. The weirdest Cleveland of all is Mo’s kid brother Howdy or Howard (Crispin Glover), a highly affected 21-year-old dandy in leather who composes strange pieces on the guitar and considers himself engaged to Stephanie (Jenny Wright), the daughter of the family’s gardener.

Following rather closely Mary Robison’s Oh!, the nine-year-old novel on which it’s based, Twister, like the family it depicts, takes a bit of getting used to — both its characters and its circumspect way of acquainting us with them — but it grows in depth and flavor as it proceeds. Mo despises Chris, and doesn’t want to let him back in the house when he shows up, but the movie makes a point of never giving us any explanation for either why he left or why she doesn’t want him back — apart from suggesting a bit of paranoia on Mo’s part. (She thinks he’s somehow responsible, for instance, for the helicopter that wakes her up in her sleeping bag the morning he arrives.) Howdy can be pretty impenetrable as well, and the movie is constructed so that most of the story is over before we get certain relevant details of family history — in particular, some crucial facts about the missing mother.

This kind of indirection, which may seem at first like a kind of narrative dawdling, is actually central to Almereyda’s strategies. Every unhappy family also has a peculiar language all its own, and most of Twister is devoted to familiarizing us with the Clevelands’ particular language. In order to do so, it has to let go of the world outside the Cleveland household, which we catch only through oblique glimpses. Even the title tornado, which sweeps through the town at one point, is basically an offscreen affair that we’re made aware of through TV reports and the twister’s visible aftermath. (Incidentally, the relation of a Kansas tornado to The Wizard of Oz isn’t lost on Almereyda, but unlike David Lynch’s evocations of the same movie in Wild at Heart, Almereyda’s references to the film — such as Virginia’s Dorothy-like costume on Wonderbox — are charmingly suggestive.) For a good deal of time, we’re carried along by offhand details and glancing moments: Violet vacuuming the bottom of a swimming pool; Virginia’s cheerful remark about the “major food groups”; the silent presence, at different points, of a huge inflated dragon and a real-life pony in the Cleveland living room; a striking monologue in a bar about the low divorce rate in Japan (delivered in a cameo by Ron Vawter of sex, lies, and videotape).

It’s an indirect form of story telling that eventually pays off, because by the end of the movie we’re no longer estranged from these people. When, for instance, Chris finally regains Mo’s love and trust by committing a mad act all his own, and Mo rationalizes it by declaring “It’s a symbol,” it’s pretty clear what she means, even if it’s hard to explain, because by now we’re acquainted with the Clevelands’ language, their behavior and style of thinking. (Large-screen TVs play an important role in the Cleveland household, and part of Almereyda’s offbeat inventiveness can be seen in the way that he stages several important scenes in front of images on the tube. The juxtapositions are always odd and never obvious; at one point, the material that’s used is from video artist Bill Viola.)

Though Twister was completed last year, its distributor, Vestron, went out of business shortly after it was finished and only a few weeks before it was scheduled to open. While it has subsequently come out on video, the elephants’ graveyard of homeless movies, it also got a second lease on life when New York’s Anthology Film Archives gave it an extended run earlier this year, earning it favorable responses from both the Village Voice and the New York Times and now a limited run at the Film Center.

For nearly a decade Michael Almereyda has made his living — in the distinguished Hollywood tradition — writing mainly unproduced scripts. The first of these, about inventor Nikola Tesla, was never sold, although at one point Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski had plans to direct it; the second, an adaptation of the comic strip Mandrake the Magician, was commissioned but got no further; another script, with a time-travel theme, attracted the interest of stage director Peter Sellars but never got off the ground. Almereyda is also one of the many people who worked on various early versions of Total Recall (for Bruce Beresford, the director of Driving Miss Daisy), and he also wrote a draft of Wim Wenders’s feature in progress, Until the End of the World. In all this time — about a decade in all — only two of Almereyda’s projects reached the screen, both in 1987: Hero of Our Time, a striking 35-millimeter black-and-white short starring Dennis Hopper, which Almereyda produced and directed and which hasn’t yet made it to Chicago, and Cherry 2000, a fitfully interesting SF picture with Melanie Griffith, directed and partially rewritten by Steve DeJarnatt, which is available in this neck of the woods only on video.

In Twister, his first feature, Almereyda is only just getting started as a director, and not all of his offbeat ideas work. (When an eccentric German doctor turns up briefly in the plot, he may be one oddball too many.) The totally inappropriate score, by Hans Zimmer, has the bad taste to give us a hymnlike organ theme for the appearances of the born-again Virginia (unbalancing Chiles’s hilarious and superbly underplayed performance) and mushy romantic stuff to accompany Chris and Mo. But Almereyda is on the whole beautifully served by his cast, with even McDermott, in his relatively straight part of Chris, grabbing out attention, interest, and sympathy, and Amis and Woodard providing a steady stream of little surprises. (Only Stanton seems a mite uncomfortable in these unorthodox surroundings; it’s possible that comedy of this oblique sort isn’t really his forte.)

Crispin Glover’s Howdy, on the other hand — an acting job that might be said to go beyond mannerism, in the spirit of Dennis Weaver’s night porter in Touch of Evil — is the movie’s real centerpiece; it’s a performance that may drive you up the wall before you catch on to its goofy rhythms and stresses, but it’s as singular and as unforgettable as his wobbly guitar music and vocals (which Glover composed). So much of it is a matter of delivery that it’s not worth quoting in print, but I can’t resist revealing one speech that Almereyda manages to shoehorn into the plot, concerning a very minor offscreen character named Jim and delivered in a barn by William S. Burroughs: “Jim? Jim got kicked in the head by a horse back in February. Went around killing horses for a while, then he ate the insides of a clock and he died.” Hearing Burroughs say it may alone be worth the price of admission.