From the Chicago Reader (January 8, 1993). — J.R.

A few years ago, world cinema received a shot in the arm from so-called glasnost movies from the former Soviet Union — pictures that had been shelved due to various forms of censorship, mostly political, and were finally seeing the light of day thanks to the relaxation or near dissolution of state pressures. The thought of an American glasnost may seem a little farfetched. But if we start to look at the awesome control exerted by multinational corporations over what we see, particularly in mainstream movies, the definition of what is and isn’t permissible — or, in business terms, what is “viable,” which in this country often comes to the same thing — may seem comparably restricted.

The best movies of 1992 weren’t exactly censored; but given the profound lack of media attention they received they would have achieved much more reality in most people’s minds if they had been. And nothing short of an American-style glasnost would give these films the cultural centrality they deserve. Only three of them received extended theatrical runs in Chicago, and perhaps only one or two got so much as a mention on Entertainment Tonight or in Time, Newsweek, or Entertainment Weekly. Read more

Written as a column for the May-June 1977 Film Comment. Some of the details here are dated, I think, in an interesting manner — especially the discussion of “Disco-Vision”. I should add that the only version of MIKEY AND NICKY that had been released in the mid-70s was an unfinished edit by Elaine May that the studio had taken away from her and put out without her consent. -– J.R.

***

The world had gone crazy, said the crazy man in his cell. What was nutty was that the movie folk were trafficking in illusions in the real world but the real world thought that its reality could only be found in the illusions. Two sets of maniacs.

– Walker Percy, Lancelot

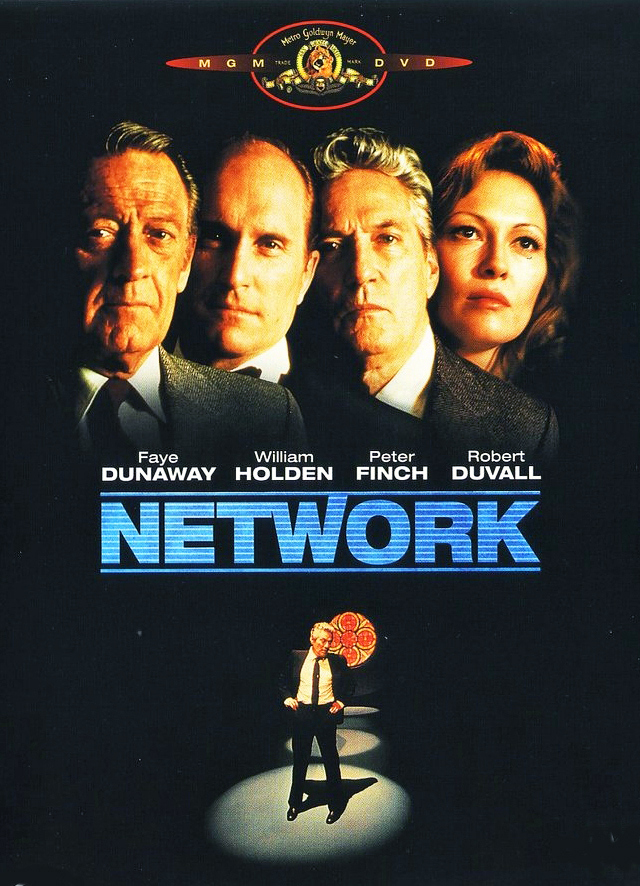

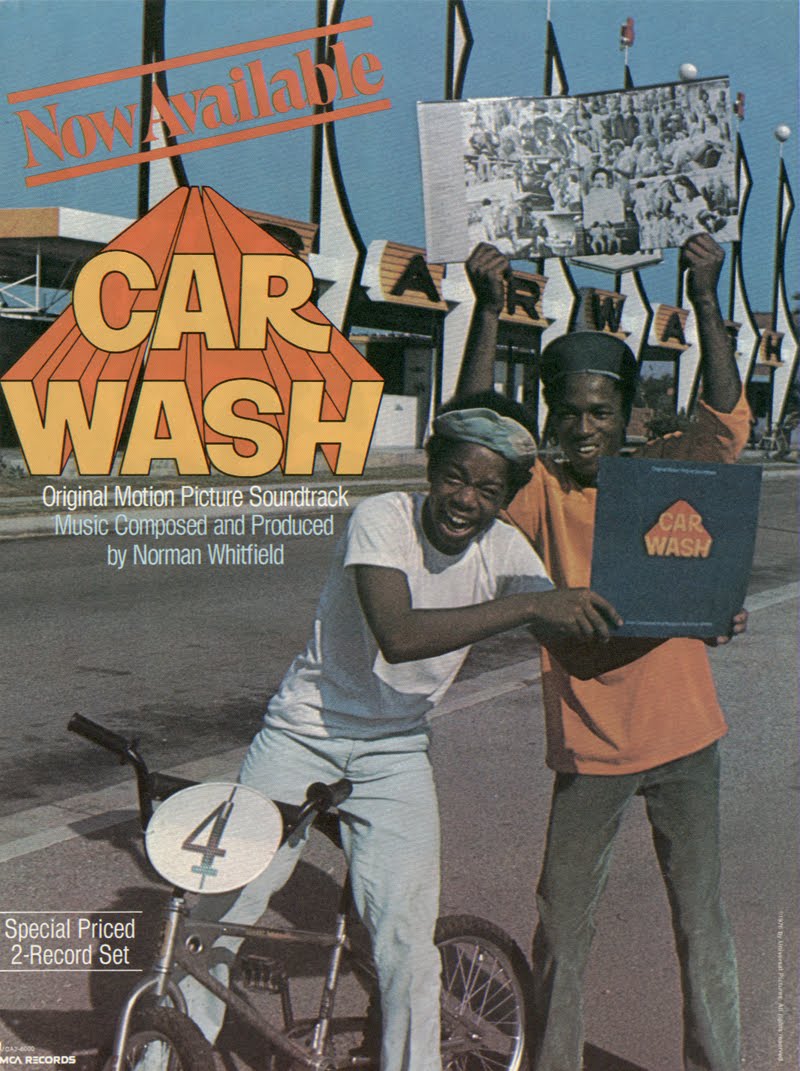

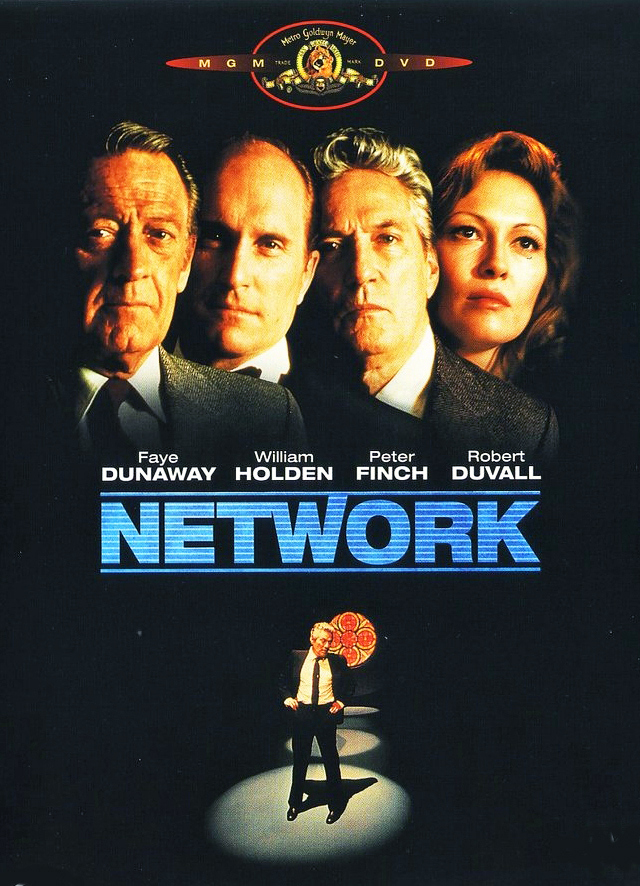

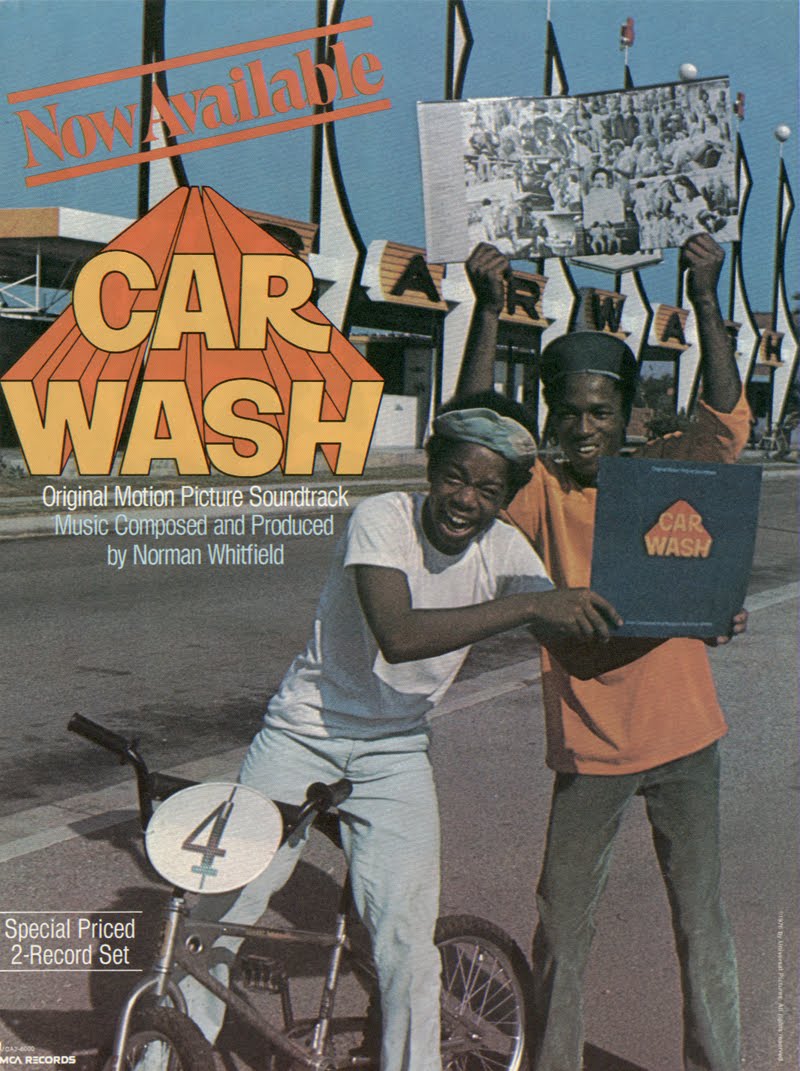

Compare the ads for NETWORK and CARWASH. The former conjures up a hot exposé, a “real” behind-the-scenes glimpse of What Goes On behind the moneyed façade of big-time broadcasting; the latter suggests a frivolous, “irresponsible” fantasy to be seen for fun, not edification. Moving back to the U.S. after over seven years abroad — a sudden shift from reflective Paris chrome and ashen London gray to La Jolla baby-blue, from cinema to some medieval state of pre-cinema or post-Cinema — the foreignness and familiarity of the country both seem epitomized by the absurdity of that cockeyed distinction, which virtually gets it all backwards. Read more

Written in late November 2013 for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

En movimiento: The Season of Critical Inflation

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Am I turning into a 70-year-old grouch? Writing during the last weeks of 2013 — specifically a period of receiving screeners in the mail and rushing off to various catch-up screenings, a time when most of the ten-best lists are being compiled — I repeatedly have the sensation that many of my most sophisticated colleagues are inflating the value of several recent releases. And my problem isn’t coming up with ten films that I support but trying to figure out why so many of the high-profile favorites of others seem so overrated to me. All of these films have their virtues, but I still doubt that they can survive many of the exaggerated claims being made on their behalf.

Such as:

Gravity, hailed by both David Bordwell and J. Hoberman as a rare and groundbreaking fusion of Hollywood and experimental filmmaking, and not merely an extremely well-tooled amusement-park ride, is now being touted as a natural descendent of both Michael Snow’s La région central as well as 2001: A Space Odyssey, as if its metaphysical and philosophical dimensions were somehow comparable. Read more

This profile was published without title in the December 1983 issue of Omni, in a section simply called “The Arts”. -– J.R.

It makes perfect sense that Manuel De Landa, a thirty-year-old Mexican anarchist filmmaker who specializes in the aesthetics of outrage, inhabits a midtown Manhattan apartment so tidy and upstanding that it could almost belong to a divinity student. The point seems to be that if you want to shake the civilized world at its foundations, it helps your credibility if you wear a jacket and tie — especially if you speak with an accent that makes you sound like Father Guido Sarducci. For a talented artist who has an asocial image to sell and a highly social way of putting it across, it isn’t surprising that De Landa makes wild, aggressive films that leap all over the place while standing absolutely still. In The Itch Scratch Itch Cycle (1977) and Incontinence: A Diarrhetic Flow of Mismatches (1978),quarreling couples in tacky settings are subjected to all kinds of optical violence:The camera moves around them in the shape of a figure eight, or De Landa crazily cuts back and forth between two static shots of the principals screaming at each other — as if he were a mad scientist, controlling their shrieks with the twist of a knob. Read more

For me the most interesting “ten best” list included in the January-February 2009 issue of Film Comment is the dozen titles offered by my favorite Japanese film critic, Shigehiko Hasumi. And what’s especially interesting about his list is the inclusion of Leos Carax’s Merde — the middle episode in the three-part feature Tokyo! (2008), flanked by contributions from Michel Gondry and Joon-ho Bong. Decidedly over-the-top in both theme and style as well as execution, and starring former circus acrobat Denis Lavant, who also plays the lead role in Carax’s first three features — an actor who’s surely even more important to this filmmaker’s work than Jean-Pierre Léaud was to the early features of Truffaut — Merde is a provocation and something of an anomaly, even for someone as eclectic as Carax. (It’s also his first film of any length since his 1999 Pola X, his only major film without Lavant.)

Clearly inspired, at least in its opening stretches, by Jean-Louis Barrault in Jean Renoir’s odd Jekyll-and-Hyde adaptation, Le Testament du docteur Cordelier (1961) [see below], Lavant plays a monster who emerges from the Tokyo sewers to wreak random and violent havoc on Tokyo pedestrians until he gets brought to trial, where he gets defended by an equally strident French lawyer (Jean-François Balmer, in a performance that’s almost as extravagant as Lavant’s). Read more

This article began as a lecture delivered on April 1, 2001 at the conference “Women and Iranian Cinema,” held at the University of Virginia and organized by Richard Herskowitz and Farzaneh Milani. Two years later it appeared in French translation in Cinéma/06, then in a booklet accompanying Facets Video’s DVD release of The House is Black in 2005, and it has also appeared in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (University of Chicago Press, 2010). — J.R.

The Iranian New Wave is not one but many potential movements, each one with a somewhat different time frame and honor roll. Although I started hearing this term in the early 1990s, around the same time I first became acquainted with the films of Abbas Kiarostami, it only started kicking in for me as a genuine movement — that is, a discernible tendency in terms of social and political concern, poetics, and overall quality — towards the end of that decade.

Some commentators — including Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa — have plausibly cited Sohrab Shahid Saless’s A Simple Event (1973) (1) as a seminal work, and another key founding gesture, pointing to a quite different definition and history, would be Kiarostami’s Close-up (1990) (2). Read more

Written circa June 2010 and previously unpublished. — J.R.

I can still recall the amusement of Penelope Houston — my boss, during the mid-1970s, when I was working for British Film Institute’s Editorial Department, on the staffs of Sight and Sound and Monthly Film Bulletin — whenever she came across routine references to directors Samuel Fuller and Douglas Sirk as “neglected” figures. Even though very few Anglo-American cinephiles could have even identified Fuller and Sirk during the 1950s, when most of their major films were coming out, Penelope certainly had a point when it came to questioning how “neglected” they still were among contemporary cinephiles in the U.K., especially after the Edinburgh film festival had extensive retrospectives devoted to each of them in 1969 and 1972, respectively. By the mid-70s, at least three books about Fuller and two about Sirk were available in the U.K — none of which appeared to have the slightest effect on their status as “neglected” filmmakers, according to the usual sound-bites.

Penelope indeed had a point. But then again, so did the various teachers and journalists who described Fuller and Sirk as “neglected,” because even though one book about each figure was published in the British Film Institute’s Cinema One series (a joint effort of the BFI’s Editorial and Education Departments in which Peter Wollen had a voice as well as Penelope), these directors remained relatively shadowy figures in Sight and Sound, a quarterly in that period which had a guaranteed subscription list based on BFI membership and therefore an unparalleled degree of clout over other film magazines in the U.K. Read more

This appeared in the June 18, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

Bitter Victory

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Nicholas Ray

Written by Rene Hardy, Ray, and Gavin Lambert

With Richard Burton, Curt Jurgens, Ruth Roman, Raymond Pellegrin, Anthony Bushell, Andrew Crawford, Nigel Green, and Christopher Lee.

Jane Brand: What can I say to him?

Captain James Leith: Tell him all the things that women have always said to the men before they go to the wars. Tell him he’s a hero. Tell him he’s a good man. Tell him you’ll be waiting for him when he comes back. Tell him he’ll be making history. —Bitter Victory

This week, as part of its series devoted to war films, the Gene Siskel Film Center is showing a restored version of Nicholas Ray’s little-known masterpiece Bitter Victory—a powerful, albeit flawed, black-and-white CinemaScope feature set mainly in Libya during World War II. This 1957 film offers a radical reflection on war, and its relevance to the current war in Iraq goes beyond the desert settings and references to antiquity.

Many films are regarded as antiwar, including ones that proceed from antithetical premises; in the 60s a popular revival house in Manhattan liked to run a double bill of Grand Illusion and Paths of Glory. Read more

“I must admit,” the Bear said in an icy voice, “that I have indeed always considered death a tragedy.”

“And you were wrong,” said Paul. “A railway accident is horrible for somebody who was on the train or who had a son there. But in news reports death means exactly the same thing as in the novels of Agatha Christie, who incidentally was the greatest magician of all time, because she knew how to turn murder into amusement, and not just one murder but dozens of murders, hundreds of murders, an assembly line of murders performed for our pleasure in the extermination camp of her novels. Auschwitz is forgotten, but from the crematorium of Agatha’s novels the smoke is forever rising into the sky, and only a very naive person could maintain that it is the smoke of tragedy.”

–Milan Kundera, Immortality (1990) [10/4/09] Read more

The following was written for the Monthly Film Bulletin — a publication of the British Film Institute, where I was serving at the time as assistant editor — and it follows most of the format of that magazine by following credits (abbreviated here) with first a one-paragraph synopsis and then a one-paragraph review. (For his resourceful photo research, thanks once again to Ehsan Khoshbakht.)–J.R.

Black and Tan

U.S.A., 1929

Director: Dudley Murphy

Dist—TCB. p.c—RKO. p. sup—Dick Currier. sc—Dudley Murphy. ph—Dal Clawson. ed—Russell G. Shields. a.d—Ernest Feglé. m/songs—“Black and Tan Fantasy” by James “Bubber” Miley, Duke Ellington, “The Duke Steps Out”, “Black Beauty”, “Cotton Club Stomp”, “Hot Feet”, “Same Train” by Duke Ellington, performed by—Duke Ellington and His Cotton Club Orchestra: Arthur Whetsol, Freddy Jenkins, Cootie Williams (trumpets), Barney Bigard (clarinet), Johnny Hodges (alto sax), Harry Carney (baritone sax), Joe Nanton (trombone), Fred Guy (banjo), Wellman Braud (bass), Sonny Greer (drums), Duke Ellington (piano), (on “Same Train”, “Black and Tan Fantasy”) The Hall Johnson Choir. sd. rec—Carl Dreher. with—Duke Ellington and His Cotton Club Orchestra, Fredi Washington, The Hall Johnson Choir. 683 ft. 19 min. (19 mm).

Duke Ellington rehearses his “Black and Tan Fantasy” for a club date in his flat with trumpet Arthur Whetsol until interrupted by two men from the piano company, sent to remove the instrument because he has fallen behind in the payments. Read more

Here is the first review I ever wrote of a Pynchon novel, published in my college newspaper and signed “Jon Rosenbaum”. In fact, although I never reviewed Slow Learner, Pynchon’s collection of early stories, I suppose it could be said that I’ve reviewed all his novels to date, because this brief review in the Bard Observer begins with a two-paragraph review of V.

I’ll also be posting, separately and in the near future, my review of Mason & Dixon, which originally appeared in In These Times. And my reviews of Gravity’s Rainbow (for the Village Voice) and of Vineland and Against the Day (both in the Chicago Reader) can be found elsewhere on this site.

One possible point of interest about this piece of juvenilia is my early comparison of Pynchon with Rivette in relation to what might be called the poetics of paranoia, a subject I would return to. For whatever it’s worth, the disappointment I’ve generally felt regarding Pynchon’s post-70s work is matched by the overall disappointment I’ve felt regarding Rivette’s post-70s work, and in both cases I’ve felt guilty about this, because the work I prefer tends to be less sane (and therefore less conventional and more avant-garde) than the work that follows it. Read more

Written for the Fall 2016 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

DVD Awards 2016, Il Cinema Ritrovato

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Lucien Logette, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. (Although Mark McElhatten wasn’t able to attend the festival this year, he has continued to function as a very active member of the jury.)

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES

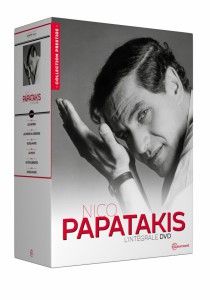

Coffret Nico Papatakis (France, 1963-92) (Gaumont Vidéo, DVD). A comprehensive and cogent presentation of a neglected filmmaker from Ethiopia and a singular cultural figure in postwar France who ran an existentialist cabaret, produced major films by Jean Genet and John Cassavetes, gave the German singer Nico her name, and made many striking films over four decades. (JR)

BEST DVD SERIES

Coffret Collection 120 ans n.1 1885-1929 (France, 1885-1929) (Gaumont Vidéo, DVD). To celebrate its 120 years of activity in the film industry, Gaumont has published a series of nine beautiful box sets that summarize the whole history of cinema. Divided by decades, the box sets consist of 20 to 35 DVDs with the most representative films marked with a daisy symbol. The editions include films made by Alice Guy, Louis Feuillade, Dreville, Duvivier, Gabin, Louis de Funès, Pialat, and Deville, but also masterpieces by Losey, Fellini or Bergman that the French company co-produced. Read more

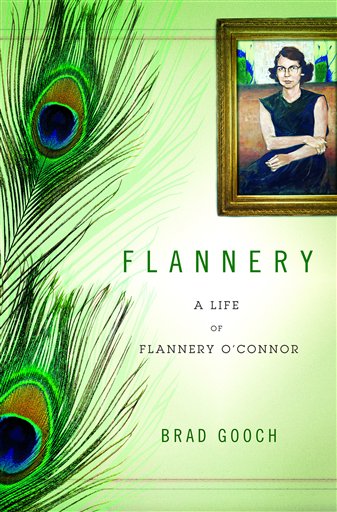

FLANNERY: A LIFE OF FLANNERY O’CONNOR by Brad Gooch (New York/Boston/London: Little, Brown and Company), 2009, 449 pp.

So far, I’ve basically been reading in and around this book rather than reading it, so I can’t with a clear conscience make it “recommended reading”, at least not yet (something I can do for Wendy Lesser’s astute and very thoughtful review of it in a recent Bookforum). I can, however, pick a bone with what I consider a couple of significant omissions: neither the names “Nathanael West” nor “Stanley Edgar Hyman” appears in the Index. The latter, who wrote a superb monograph on O’Connor that was published in 1966 (no. 54 in the University of Minnesota Pamphlets on American Writers), argues rather persuasively (on p. 43) that the “writer who most influenced [O’Connor], at least in her first books, is Nathanael West. Wise Blood is clearly modeled on Miss Lonelyhearts (as no reviewer noticed at the time),” and then goes on to cite four examples of her prose that amply bear this out: “Hazel Motes has a nose `like a shrike’s bill’; after he goes to bed with Leora Watts, Haze feels ‘like something washed ashore on her’; Sabbath Lily’s correspondence with a newspaper advice-columnist is purest West; and all the rocks in Wise Blood recall the rock Miss Lonelyhearts first contains in his gut and then becomes, the rock on which the new Peter will found the new Church.” Read more