From the January 19, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Cafe Lumiere

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien

Written by Hou and Chu T’ien-wen

With Yo Hitoto, Tadanobu Asano, Masato Hagiwara, Kimiko Yo, and Nenji Kobayashi

Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World

*** (A must see)

Directed and written by Albert Brooks

With Brooks, Sheetal Sheth, John Carroll Lynch, Jon Tenney, and Fred Dalton Thompson

“It’s very difficult to cross national borders and shoot a film about a different culture. How many films have you seen that do that successfully? There are very few. The reason is very simple. When we look at films [about our own country] made by foreign companies, they’re not accurate. . . . But it’s an interesting challenge.”

This could be Albert Brooks talking about the making of his funny new feature, Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World, most of it filmed in New Delhi. But it’s actually Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien speaking about Cafe Lumiere, which was shot in Japan. Both filmmakers are pushing 60, and both prefer filming in long shot and extended takes. And both their movies are acute, measured observations of contemporary life and thought, whether we happen to be based in LA or Tokyo.

Cafe Lumiere (2003) was commissioned by the Japanese studio Shochiku, which asked Hou to create an homage to its most famous house director, Yasujiro Ozu, in celebration of the centennial of his birth. It’s a return to form for Hou, after the formalism of Flowers of Shanghai (1998) and the emptiness of Millennium Mambo (2001 — and his best film since The Puppetmaster (1993). It’s also his most minimalist effort to date, slow to reveal its depths and beauties, and it marks a rejuvenation of his art, confirmed by his subsequent film, the far from minimalist Three Times (2005), shot in Taiwan.

Cafe Lumiere is a look at everyday Japanese life and how it’s changed since Ozu’s heyday. It uses some of Ozu’s visual motifs — trains, clotheslines — and it beautifully reflects what English critic Tony Rayns has called the “persuasive” unassertiveness that characterizes much of Ozu’s late work. It’s an outsider’s view of Japan that’s really a two-way mirror, because the obsessive preoccupation of its 23-year-old Japanese heroine, Yoko (Yo Hitoto), a freelance writer based in Tokyo, is investigating the life of Taiwanese classical composer Jiang Wenye. Roughly a contemporary of Ozu, Jiang was born in Taiwan and educated in Japan, then spent most of the remainder of his life in mainland China. The only music heard in the film, besides a pop song over the final credits, is a selection of piano pieces he composed in Japan during the 1920s and ’30s; they provide a historical and cultural filter through which we perceive the present.

Yoko has just returned from Taiwan, where she’s been researching Jiang’s roots while teaching Japanese. She’s pregnant with the child of one of her students, and she tells her elderly parents that she intends to raise the child alone — a clear sign of the differences between Japanese life today and the life chronicled by Ozu.

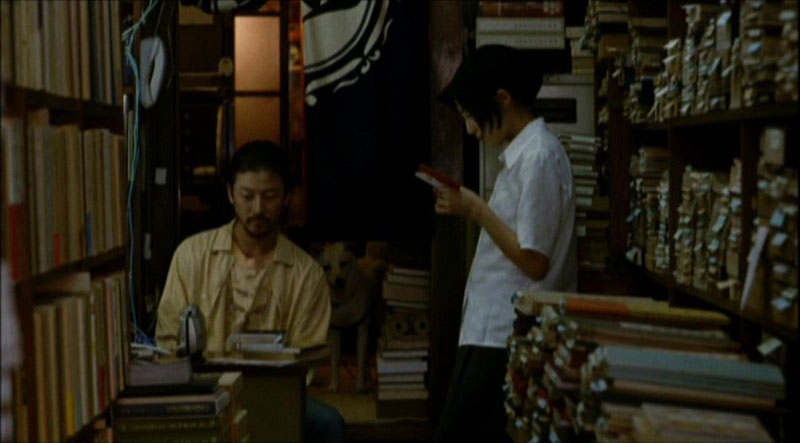

Taiwan was a Japanese colony for 50 years, until 1945, only two years before Hou was born, and Japanese culture undoubtedly had a lingering effect on many aspects of Taiwanese life. Hou, who’s long had an interest in Ozu, shares the older director’s fascination with trains, and in Cafe Lumiere one of Yoko’s friends, Hajime (Tadanobu Asano), who runs a used-book store, is obsessed with recording the sounds of trains.

Like Ozu, Hou is mainly nonjudgmental about his characters, though he does manage to suggest over the course of his almost plotless narrative that Yoko and Hajime are somewhat indiscriminate collectors whose fascination with music and trains may show more compulsiveness than passion. Yet if there’s a critique of contemporary life that could be drawn from this observation — also hinted at in the film’s Japanese title, Coffee Jikou (meaning “coffee, time, light”) — this is only one aspect of Hou’s serene clarity.

***

The clarity of Albert Brooks is far from serene, and Sony backed away from distributing Looking for Comedy in The Muslim World last year after Brooks refused to change its honestly descriptive and perfect title. What makes his clarity especially welcome now is its frank admission of American ignorance about Muslims —- coming at a time when the few other Hollywood movies dealing with Muslims, like Syriana or Munich, seem more interested in making non-Islamic viewers feel wised up. By contrast, an honest admission of ignorance can sometimes serve as a first step towards lucidity. Brooks plays a blundering fool who heads a skimpy and vague initiative of Bush’s State Department to study what makes people laugh in India and Pakistan — a reminder of the kind of mistakes the U.S. can make in the Third World, even with noble intentions. So the focus here is less on those countries than on our inadequate ways of understanding them. Furthermore, by giving the fool his own name and career, Brooks pushes self- scrutiny beyond national terms and into something far more personal.

This is the triumph of his seventh feature, but it’s also its limitation, because it sometimes suggests competing agendas —- critiquing myopic self-absorption (including Brooks’s failure as a comic performer in New Delhi when he revives some of his old routines, ignoring that Halloween and ventriloquism may not be local reference points), yet at other times asking us to identify with his bemusement. And to complicate matters further, his real-life concerns about his dwindling career and his aging are placed front and center in the opening scene. They’re plainly what motivate his character to accept this muddled project and agree to return from India and Pakistan with a 500-page report, figuring that a Freedom Medal will boost his image. But satire inflected by sharp self-mockery (such as Brooks’s embarrassment about being Jewish in India) doesn’t always mesh well with the sentimental genre conventions (Brooks sweetly advising his Indian girl Friday about her jealous boyfriend).

As Brooks has noted, playing a semifictional character named Albert Brooks, which he already did in Real Life (1979), is similar to what Jack Benny used to do on radio and TV. But there’s a significant difference between the obnoxiously aggressive Brooks in that first feature and the more passively reactive one here, and I’m not convinced it’s a comic gain.

Still, I’ve never come close to disliking any Brooks feature; each one is brilliantly conceptualized and deftly executed, and this one’s no exception. There’s been a lessening of energy and invention since his first three features that seems tied to his efforts to score commercially, yielding the willful happy endings of Defending Your Life (1991) and Mother (1996), the awkward guest-star appearances in The Muse (1999), and the determination here not to be scathing while remaining pointed and provocative. But we’re very lucky that he continues to make movies, and the laughs offered here are genuinely cathartic.