This is the first article I ever wrote for Stop Smiling — their “auteur issue” (no. 23) in 2005. Like virtually all Welles reporting, this is of course drastically out of date, but often in a good way; it’s delightful to see how much more of his work has become available over the past 17 years. — J.R.

If Orson Welles were still alive, he would have turned 90 last May 6th. Chances are, no matter what he did in his final years, a certain number of people would still be griping that he never lived up to his promise. But I

wouldn’t be one of them.

This Midwestern whiz kid, a master of radio, theater, and film, terrorized the populace when he was 23 with a mockumentary radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds that was taken for real. At 25 he scandalized Hollywood with a first feature called Citizen Kane that ridiculed newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Welles was clearly expected to cause a sensation regardless of what he did after this. But to manage that, he would have needed continued public visibility, which Welles rarely had after those two early peaks. And in fact he was after more than sensation.

In order to claim that Welles let us down, we’d first have to establish both what he tried to do and what he accomplished — and something tells me that we aren’t about to have the last word on either matter. Despite the compulsive mythologizing that tends to fill in most of the blanks on Welles, we still know zip about him. People remember his spreading girth, his wine commercials, and some of his talkshow appearances where he often performed magic tricks, but are often vaguer about his serious work as a filmmaker. Much of this surely stems from Welles’ very theatrical way of teasing his audience’s imagination — which still does wonders for his work, but has also played havoc with his posthumous image. Some of the most popular and least informed biographies, like David Thomson’s Rosebud, consist of little more than highly speculative character assassination. Part of Thomson’s winning formula is to assure himself and others he doesn’t even need to see Welles’ unreleased features to know that they’d be disappointments. I’m sure this must simplify matters for Thomson; but I’ve been fortunate enough to have seen large sections of all these legendary works, and I beg to differ.

Having met Welles once —- in Paris, when I was just getting started as a critic, and he generously responded to my letter asking him about his first film script by inviting me to lunch — I’d also dispute Thomson’s portrait of the man as a self-serving liar. If anything, he tended to be so self-critical that his own barbs were usually far more convincing than those of others. I think he continues to trouble the mainstream largely because his very methods and their implied values —- above all, a preference for process over product –continue to pose an ideological challenge to the film industry. And meanwhile, the pathetic efforts to remake Welles films such as The Magnificent Ambersons (his second feature) for TV or rewrite and film his unrealized scripts like The Big Brass Ring have only muddied the waters further.

It’s also worth stressing that the ultimate American auteur wasn’t even much of an auteurist, generally valuing the work of actors over that of directors and periodically insisting that “Writers should have the first and last word in moviemaking, the only better alternative being the writer-director, with stress on the first word.” This is a bit hard to square with the insistence of Pauline Kael and biographer Simon Callow that Welles wasn’t really a writer at all — a myth they both took over uncritically from John Houseman, Welles’ erstwhile business manager, script editor, and producer

.

Paradoxically, Houseman could have legitimately claimed some secondary credit for the Kane script himself. He probably had good reasons to feel spiteful about Welles after the dissolution of their partnership (which had included his editing of Herman J. Mankiewicz’s work on the Kane script), and the form his spite took was denying that Welles wrote any part of Kane — despite all the clinching textual evidence to the contrary (including Houseman’s own correspondence as well as the actual scripts). Even after this was conclusively established in 1978, by Robert L. Carringer in the academic journal Critical Inquiry, Kael’s 1971 anti-auteurist screed against Welles continued to carry such mythic weight that she didn’t even deign to add a correcting footnote when she reprinted her essay “Raising Kane” in her final collection, For Keeps.

By that time, she’d already transformed Kane in the public mind from an independent art film to a “classic” Hollywood newspaper comedy. From then on, Welles was seen more as a failed industry professional than as an independent rebel who succeeded momentarily in taking over a Hollywood studio. But the final irony about her charge that he wasn’t a writer is that one of his most convincing refutations of this —- a lengthy, beautifully written rebuttal, published in the October 1972 Esquire and entitled “The Kane Mutiny” —- was signed by Peter Bogdanovich, though we now know that it was basically ghostwritten by Welles.

***

Even if we concede that Welles was a habitual overreacher, it’s not widely known that he was working on at least four of his own independent features the week that he died, because we customarily gauge such work according to what gets released and hyped by the studios. And restricting ourselves to the thirteen features released during his life — the same number released by the far less reviled Stanley Kubrick, who also died at 70 — means barely scratching the surface.

Over the decades in which I’ve been researching his work, I’ve found that Welles rarely made false claims about his works in progress the way that Truman Capote did about his largely apocryphal novel Answered Prayers. On the contrary, there always turns out to be more of Welles’ private work squirreled away, not less, than his interviews suggest. Yet the continuing invisibility of Don Quixote, The Deep, and The Other Side of the Wind has led many to conclude that the man must have been a fraud, because otherwise all three would surely be at our video stores by now. (In fact, a horrendous edit of Welles’ sublime Quixote slapped together by Jess Franco, the busiest shlock director in Spain, is readily available in Europe, but this only makes matters worse.)

Among other Welles films that remain relatively unseeable —- not even counting such classics as Chimes at Midnight (1964) and The Immortal Story (1968) that can be seen more easily in Europe — are The Fountain of Youth, a terrific TV pilot from 1956 made in Hollywood; Viva Italia!, a not so terrific TV pilot made in Europe shortly afterwards; a 40-minute condensation of The Merchant of Venice in color from around 1970; a brilliant feature-length essay from 1978, Filming Othello; and many late fragments, including material shot for The Magic Show and The Dreamers. One might further decry the fact that several TV series made in Europe are also out of reach if it weren’t for the fact that the best of these, the 1955 Around the World with Orson Welles, came out here on DVD in 1999 and has received virtually no attention at all. And this is basically the point: reasons for our lack of access vary enormously, from studio indifference (The Fountain of Youth) to a stolen reel (The Merchant of Venice), but it’s most often the simple lack of commercial or public interest —- which usually has nothing to do with the work’s value or even its eventual popularity. It’s surely not frivolous to surmise that if Citizen Kane were made today and had to pass test-market screenings, it would probably flunk. (The only exception was the relatively unmemorable but profitable 1946 thriller The Stranger, made by Welles in order to prove he could deliver the goods if he had to.)

I think we’re far too willing to let the media and their equation of visibility with importance rule on such matters, allowing our anxiety about Welles’ aberrant working methods to dictate our skewered sense of the man. But the anomaly of his career isn’t that he didn’t make more Hollywood features but that he made any at all. Despite our image of him as a showman and a showoff, there are few contemporary artists who managed to keep more of their life and work so firmly under wraps. Is it any wonder that most of his films — from Kane to The Lady from Shanghai to Touch of Evil to Chimes at Midnight to F for Fake —- are about the disparity between public lives and private emotions?

Because he never had any interest in doing the same thing twice, those who chide him for never having made “another” Citizen Kane are really blaming him for his failure to commodify himself as a filmmaker —- which always kept his public a few steps behind him. They also conveniently overlook that Welles had only one crack at both final cut and the resources of a Hollywood studio, which happened to come on his first feature, and after that, whenever he had to choose between studio resources and final cut, he usually opted for the latter. That’s why less than half of his thirteen released features came from Hollywood, and, apart from the 1958 Touch of Evil, nothing made after 1948.

The biggest scandal was that he enjoyed working on his own low-budget productions so much that he spent most of his career subsidizing them with his hackwork —- though it’s still most often the hackwork like the wine commercials that gets remembered. (This pattern got launched during the 30s, when he was often supporting his experimental stage productions with the income he made as an anonymous radio actor.) The reasons why most of these films have never reached us are multiple, but two of the more pertinent factors are that he was a terrible businessman and that he tended to keep revising his work whenever he could. For instance, there are at least two Welles-edited versions of Othello, his first independent feature. The first one tied for the Golden Palm at Cannes in 1952 and the second — which opened in the U.S. in 1955 and formed the basis for the so-called “restored” (actually somewhat revised and mangled) 1992 rerelease —- isn’t only recut but remixed. A French scholar, François Thomas, recently figured out that Welles redubbed the actress playing Desdemona, Suzanne Clothier, with the voice of Gudrun Ure, the actress who’d played the same part in Welles’ quite different 1951 London stage production.

Thanks to the common misperception that something called “the Estate of Orson Welles” actually exists, bolstered by a web site calling itself that, Welles’ youngest daughter Beatrice has been claiming rights to almost everything bearing her father’s name, and even tried to halt a screening of Citizen Kane in London a couple of years ago on that basis. But in fact, the only released film that Welles owned himself when he died was Othello; he willed it to his widow Paolo Mori, and Beatrice inherited it from her mother after she died in an auto accident a year later. All his unreleased and unfinished work he willed to his mistress and collaborator Oja Kodar, a Croatian sculptor who remains best known for her appearance in Welles’ 1973 F for Fake, a film she also helped to write. (She also cowrote and appeared in The Other Side of the Wind, and the titles for both films were selected by her.)

There’s some reason to suspect that Welles actively sabotaged in advance any posthumous efforts to assemble Don Quixote the way he would have done it himself. In effect, he appears to have said at one time or another to many of the people he was closest to, “You are the only one I can trust” —- thereby virtually guaranteeing that they’d be suing one another indefinitely after his death to claim rights to this work.

I admit this sounds perverse; but given how much pleasure Welles derived from this low-budget project and how poorly it probably would have been received had he released it during his lifetime, it may have been less perverse than it sounds. When I met him in 1972, he told me the film was nearly done, but he didn’t want it to compete with the upcoming movie of the stage musical Man of La Mancha. Considering how poor the American critical receptions were of his 1948 Macbeth and his Othello —- both compared unfavorably to Laurence Olivier’s much slicker Shakespeare films —- he probably had a point.

“You don’t imagine that posterity’s judgment, do you?” says Kim Menaker in Welles’s script for The Big Brass Ring, a character he planned to play himself. “Posterity is a whim. A shapeless litter of old bones: the midden of a vulgar beast: the most capricious and immense mass-public of them all —- the dead.” Perhaps even more to the point, he said to Kenneth Tynan in 1967, “Up to a point, I have to be successful in order to operate. But I think it’s corrupting to care about success; and nothing could be more vulgar than to worry about posterity.” This is the testament of a subversive artist who stayed subversive, and if we have to keep scampering after his lost work as a consequence, I suspect that we’ll ultimately be richer for it.

***

Sidebar: Released & Unreleased Orson Welles Films

1941: Citizen Kane. Grim and funny, scary and exuberant, though not always at the same time. The movie that’s most inspired other wet-noses to become filmmakers, though it didn’t turn a profit. (Hearst papers refused to run ads, theater chains were too chicken to show it, and the Academy people, jealous of Welles’ unprecedented freedom and right to final cut, mainly snubbed the movie, apart from an Oscar for best script.)

1942: The Magnificent Ambersons. Very personal adaptation of the Booth Tarkington novel about declining Midwestern aristocracy during the early 20th century. Eviscerated and partly reshot by RKO while Welles was in Brazil shooting another feature (see It’s All True in Sidebar 2).

1946: The Stranger. Welles plays a Nazi in hiding hunted down by Edward G. Robinson. Not so many tilted camera angles as in the previous two films, and much bigger boxoffice.

1948: The Lady from Shanghai. Welles’ only “A” picture after Kane and Ambersons, though made for an A-minus studio, Columbia, which eliminated about half the footage. A Baroque thriller in which he costars with former wife Rita Hayworth, concluding with a memorable shootout in a Hall of Mirrors.

1948: Macbeth. Shot quickly on some of the Western sets of a “B” studio, Republic Pictures. The studio forced Welles to redub the film without Scottish accents and cut two reels, though both versions survive today and the original is better.

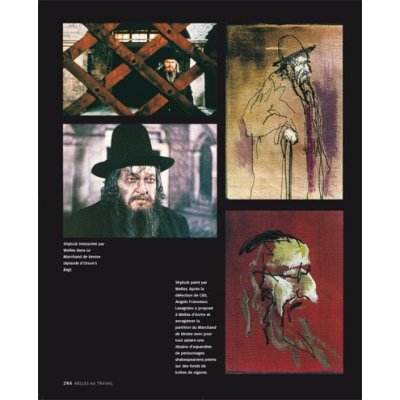

1952: Othello. Welles’s first independent and first overseas film production, shot piecemeal over three years on different continents, periodically stopping to raise enough money to continue shooting. One of his two best Shakespeare films, though available in the U.S. only with posthumously reworked music and sound effects.

1955: Mr. Arkadin. A weird fairy-tale thriller written by Welles and shot in western Europe that he wasn’t able to finish editing and which survives in many versions, including one called Confidential Report. Flawed but fascinating.

1958: Touch of Evil. Welles’ last Hollywood film — a sleazy and brilliant border-town thriller done at Universal and taken out of Welles’ hands shortly before completion. He drafted a lengthy memo to the studio that attempted to do some damage control, and a re-edit that tried to follow his suggestions, released in 1998, is the only version available today. [Update: fortunately, this is no longer true.]

1962: The Trial. Shot mainly in Zagreb and an abandoned Paris train station — a free and updated adaptation of Franz Kafka’s comic and nightmarish novel about bureaucracy and the law. As with The Stranger, this fell into public domain, so copies on video and DVD are variable.

1966: Chimes at Midnight. Welles’ Shakespearean collage about Falstaff and Prince Hal, shot cheaply in Spain, is for many his best Shakespeare adaptation and/or best film, though you have to order the DVD from Spain. Rights issues persist.

1968: The Immortal Story. An hour-long adaptation of an Isak Dinesen story made for French TV; Welles’ first released work in color. Currently available on DVD only in Italy.

1973: F For Fake. A mockumentary essay about art forger Elmyr de Hory, Clifford Irving, Howard Hughes, and Welles himself. The editing, which took Welles a solid year to complete, is exceptionally dense and tricky, but the mood is mainly lighthearted.

1979: Filming Othello. A modest but beautiful personal essay that gave Welles yet another opportunity to re-edit portions of his 1952 masterpiece. Unavailable in the U.S.

It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles. A good posthumous documentary, easy to find, about what should have been Welles’ third RKO feature —- an ambitious non-fiction anthology about Latin America, shot in Mexico and Brazil in 1942, that Welles’ was never allowed to edit. The surviving footage, in both color and black and white, is dazzling.

Don Quixote. Welles started work on this in the mid-50s and kept working on it sporadically until he died. One of his earthiest and most poetic efforts, based on what I’ve seen — adapting Cervantes by updating Spain but not Quixote or Sancho Panza — though the version edited by Jess Franco and released in Spain is a travesty.

Around the World with Orson Welles. A fascinating TV series from 1955, available on DVD, with two episodes devoted to the Basque country and one each to Paris’ Latin Quarter, Chelsea pensioners, and the Spanish bullfight. Also check out The Dominici Affair (a separate DVD) for a documentary about an unfinished episode in the same series, devoted to a true crime story set in rural France.

Orson Welles Sketch Book. Another TV series from 1955, this one an amiable talking-head affair for the BBC. Unavailable.

The Fountain of Youth. This brilliant and innovative TV pilot, produced by Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz in 1956 and based on a John Collier story, posits a different kind of televisual storytelling that never took hold. Unavailable.

Viva Italia! Another unsold TV pilot from the same period, one shot in and around Rome and featuring interviews with Gina Lollobrigida and Vittorio de Sica, among others. Shown sporadically on European TV in recent years but otherwise unavailable.

In the Land of Don Quixote. A nine-part Italian TV series consisting of home movies of Welles, his wife Paola Mori, and daughter Beatrice Welles touring Spain in the mid-60s. Amiable hackwork done in order to raise money for Don Quixote (see above), but then Jess Franco inserted chunks of this into Quixote itself, muddling matters permanently.

The Deep. A thriller set on two yachts in the Mediterranean, adapted from Charles Williams’ novel Dead Calm and shot in the 60s with the idea of doing something commercial, like The Stranger. The Munich Film Archive is currently working on a restoration.

The Merchant of Venice. A 40-minute condensation shot in color for an unfinished TV special, shot on location in 1969-70 and completed, but someone made off with one of the reels.

The Other Side of the Wind. A caustic satire about Hollywood circa 1970, much of it shot there and starring John Huston as an aging macho director on his last go-round. A much-delayed completion and airing of this late feature is periodically reported to be in the works.