From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 503). I think I must have permanently jinxed the possibility of ever becoming a friend of Pauline Kael’s by introducing myself to her after the New York Film Festival’s press screening of Get Out Your Handkerchiefs in 1978. Clearly enraptured, she promptly asked me what I thought of the film, and I replied, “Well, at least it’s better than Les valseuses,” which she deeply revered as well. — J.R.

France, 1974

Director: Bertrand Blier

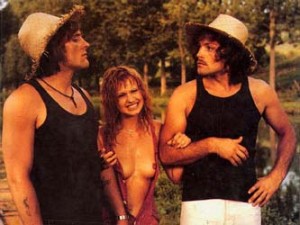

After harassing a woman in the street and stealing her purse, Jean-Claude and Pierrot steal a Citroen for the afternoon; when they return it, the hairdresser owner holds them at gunpoint until they manage to escape during a scuffle, taking the hairdresser’s girlfriend Marie-Ange with them. Pierrot, however, is shot in the groin; the two force a surgeon to treat the wound and then take his money. When they abandon another stolen car to hop a train, Jean-Claude pays a young mother to suckle Pierrot before she gets off to meet her soldier husband. They take another train to the town of Briddle, where they break into a house whose owners are away but where they excitedly discover the underwear of teenager Jacqueline. Pierrot continues to fret about being impotent, and is annoyed when Jean-Claude forcibly sodomises him; they visit Marie-Ange and take turns having sex with her, although she remains frigid. With her help, they steal money from the hairdresser and then drive to a women’s prison at Jean-Claude’s insistence, where they pick up a stranger, Jeanne, who has just been set free. After talking to a waitress about her menopause, she spends a night with Pierrot and Jean-Claude in a fancy hotel, after which she shoots herself dead in the vagina. Going through her letters, the boys discover that her son Jacques is due out of prison soon; they pick him up and invite him to join them, although they are upset when he simultaneously ends his virginity and cures Marie-Ange’s frigidity. Jacques asks to borrow their gun to rob a prison warder and his wife; shocked when he shoots the warder, Pierrot and Jean-Claude flee with the now liberated Marie-Ange. After stealing several more cars, they meet the family whose house they vandalized; Jacqueline spontaneously joins forces with them and helps them steal her parents’ car and money. They initiate her sexually, drop her off, and drive away towards further adventures.

Although Les Valseuses often registers as a French equivalent to such would-be challenges to middle- class mores as Corman’s The Wild Angels –- a form of shock titillation designed to place the audience in league with a band of macho hell-raisers, while gasping or giggling at the outrages they perpetrate -– this Gallic box-office hit differs by being slicker, more discontinuous as narrative, and a lot more smug about the goods it has to deliver. The slickness is partly derived from Stéphane Grappelli’s graceful score, which turns pseudo-Baroque when the heroes relieve Jacqueline of her virginity, and is joined by a heavenly choir as they drive off afterwards like demi-gods; it also owes something to the mainly assured performances — Gérard Depardieu, for instance, making a much more convincing hood than Peter Fonda. Served up as folk heroes, Jean-Claude and Pierrot are clearly intended to seem as cute as bugs when they run off with assorted merchandise, slap their girlfriend Marie-Ange around, scandalize others and wear matching T-shirts as they inveigh against bourgeois complacency. If they fail to develop as characters over nearly two hours of interminable rambles, this may be because writer-director Bertrand Blier is more interested in keeping them in jaunty motion than in letting us entertain much curiosity about their pasts and futures.

Thus the odd recurrence of sexual vulnerability in the plot — from Pierrot’s wound and worry about impotence to Marie-Ange’s frigidity, Jeanne’s menopause and the virginity of Jacques and Jacqueline is never utilized in any thematically or dramatically cumulative way. Similarly, Jean-Claude’s awed treatment of Jeanne is so inconsistent with his stance towards females elsewhere that one suspects this has more to do with the commanding presence of Jeanne Moreau in the role than with the character herself. Considering all the vicissitudes charted during this dispiriting romp, Making It seems a somewhat inapposite title, but the original French one is not much clearer: literally translatable as ‘the testicles’, one can’t be sure whether it refers to Pierrot’s injured parts specifically or to both of the heroes in general.