My Winter 2019 column for Cinema Scope. — J.R.

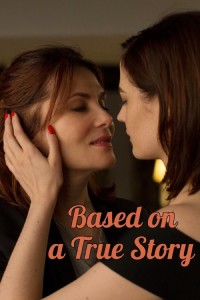

Some of Roman Polanski’s early features — Repulsion (1965), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Tess (1979) — are centred on vulnerable women, but as Bitter Moon (1992) makes abundantly clear, these are all films predicated on the male gaze, as are the more recent and more impersonal films of his that come closest to qualifying as Oscar bait (The Pianist [2002], arguably The Ghost Writer [2010], and, I would presume, An Officer and a Spy). Bitter Moon even problematizes this fact by assigning that gaze to two mainly unsympathetic males (Peter Coyote and Hugh Grant), and defining it mostly as poisonous, and Venus in Fur (2013) carries this tendency further by explicitly labelling it sexist, meanwhile making the male figure (Mathieu Almaric) almost a dead ringer for Polanski as a young man. Based on a True Story (2017), by focusing almost exclusively on two women (Emmanuelle Seigner and Eva Green), seeks to minimize the male gaze even more, not so much by problematizing it as by making it closer to irrelevant. Polanski himself comments on this fact in the interview included on the Spanish DVD of this film (apparently the only way it can be seen with English subtitles translating its French dialogue, which is how I finally managed to catch up with it).

The last three features all co-star Polanski’s wife Seigner, whom he married in 1989 and who keeps getting better and more interesting as an actress as she grows older. The latter two of these movies clearly qualify as full artistic collaborations: Seigner dominates Venus in Fur, and she was the one who proposed that Polanski adapt the novel that Based on a True Story is derived from. Yet it’s the half-century-old sexual abuse case lodged against her husband that still defines his Anglo-American media profile, not his 30-year marriage or the unmistakable feminist trappings of Venus in Fur and Based on a True Story, some traces of which are already apparent in Bitter Moon. (Significantly, the latter title alludes to the point of view of the heroine, not the hero. And even though male voices and ears control the storytelling, the film remains critical and even quite devastating about both the libertine attitudes of Coyote’s character and the puritanical attitudes of Grant’s.)

To some extent, puritanical and unreasoning Yankee taste has dictated what I take to be both the capitalist censorship of Based on a True Story and the current media profile of Polanski. See, for example, Owen Gleiberman’s review of Polanski’s An Officer and a Spy in Variety, which can chastise Polanski for personally identifying with Alfred Dreyfus (protagonist and victim of the Dreyfus Affair) only because Gleiberman won’t consider the actual and separate charges of libel that have been brought by Polanski over the past two decades (see his Wikipedia entry for details), and, like many others, assumes that only Polanski’s 50-year-old sexual transgression deserves to be mentioned or considered. The additional fact that the now octogenarian Polanski has forsaken much of the aggressive Hitchcockery of his earlier career for a more thoughtful, inquisitive, and analytical style of filmmaking that incorporates feminist insights obviously counts for zip in such a climate because it doesn’t square with such reflexes, so it has to be stricken from the public record. Much as Harvey Weinstein’s multiple artistic crimes continue to be silently excused (or implicitly endorsed), or else simply overlooked or forgotten as trivial while his sexual crimes are (deservedly) shouted from the rooftops, Polanski’s refined and sharpened positions about gender clearly have no role to play in his overall demonization. This need to keep the public happily howling with self-righteousness is undoubtedly what led a prominent and respected columnist in The Nation several years ago to confidently compare Polanski to a Nazi death-camp officer, even though she must have known that both of his parents were slaughtered in a death camp. [Tweet from Dale Edwin Wittig, 1/29/20: “One small correction: Polanski’s father survived the death camp and remarried after the war, but Polanski chose not to live with him.”]

***

On the whole, I’ve been disappointed by most of the criticism I’ve encountered about Ernst Lubitsch, including even Joseph McBride’s recent and mainly excellent How Did Lubitsch Do It?, which for me founders when it labels The Man I Killed (a.k.a. Broken Lullaby, 1932) a “misfire.” (This is admittedly a commonplace judgment—the movie failed at the box office, thus occasioning its second title — yet I’ve always regarded it as a major, deeply moving, and irreplaceable part of the Lubitsch oeuvre.) But this disappointment is alleviated by Criterion’s first-rate Blu-ray and DVD edition of Lubitsch’s swan song Cluny Brown (1946), which has the excellent idea of assigning most of its accompanying criticism to women. Especially fine is the booklet commentary by essayist Siri Hustvedt, which offers the unassailable (but generally neglected) insight that the title heroine’s obsession with and enthusiasm for plumbing registers as a rebuke to the diverse blockages and repressions, implicitly or explicitly sexual, of most of the other characters; the package also includes a lively dialogue between Molly Haskell and Farran Smith Nehme about Lubitsch’s quirky and assertive female characters, and a perceptive video by Kristin Thompson about the film’s uses of reaction shots. The only male on board here is Bernard Eisenschitz, who offers a pithy summary of Lubitsch’s career, including an astute comment on his tragic sense of history. (My only quarrel with the latter point is assigning this trait mostly to Lubitsch’s comedies, because surely the tragedy of recent history projected by The Man I Killed is central to its power.)

As for Cluny Brown itself, I must confess that its main stumbling block for me in the past has been accepting and tolerating the sheer stupidity of the heroine (Jennifer Jones) in falling for the awful village pharmacist (Richard Haydn) — unlike the all-forgiving Lubitsch himself, who is similarly magnanimous towards her clueless employers and intolerant fellow servants. But adopting Lubitsch’s understanding for these diverse nitwits and deadbeats is clearly part of this movie’s quiet ethical lessons.

***

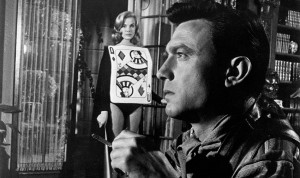

Re-seeing the “director’s cut” of William Richert’s star-packed Winter Kills on Amazon Prime, 40 years after its first release and about a month ahead of its re-release by Kino Lorber on Blu-ray and DVD, I immediately recall how this Richard Condon adaptation, like its more celebrated Condon-derived predecessor The Manchurian Candidate (1962),seems to traffic in the same sort of paranoia about conspiracies tied to the JFK assassination — with the pertinent difference that the corresponding novel and movie of The Manchurian Candidate both appeared before the assassination of JFK, whereas the book (1974) and movie (1979) of Winter Kills came afterward. And to obfuscate our sense of reality even further, Winter Kills fictionalizes the Kennedy family back in the ’60s as the Kegans, dead president included.

“Ranks with Citizen Kane as the greatest American movie of all time (Vincent Canby, The New York Times)” is the highly improbable pullquote that one currently finds affixed to Winter Kills, on Amazon and elsewhere on the internet. Is this “fake news,” or some form of genuine derangement on Canby’s part? It sounds improbable even for the Times reviewer who once suggested, a propos Michelangelo Antonioni’s Identification of a Woman (1982), that Mr. Woody Allen could teach Mr. Antonioni a thing or two about how to make an unpretentious art movie — thereby occasioning Identification’s immediate loss of its American distributor and the subsequent eclipse of Antonioni’s stateside reputation. For all those who still think that the film-within-a-film of Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind is somehow a “parody” of Antonioni (even though it doesn’t resemble Antonioni’s visual style in any particular), I suppose that Richert might similarly qualify as some sort of proto-Wellesian, but only Canby’s ghost can presume to tell us what kind.

Even so, one could counter that what Woody Allen once counterposed to Antonioni in terms of the sort of reductive pastiche Canby yearned for, Winter Kills (the movie) does to The Manchurian Candidate (the movie) in terms of making something toothless out of material that was once scary, original, and dangerous. Maybe this is because it so insistently sets itself up as a hip retread: Sterling Hayden gets a white beard and a WW2 tank for his do-over of his crazy general from Dr. Strangelove (1963), with a dollop of Robert Duvall’s swaggering Kilgore in Apocalypse Now (1979); John Huston walks through a repeat of his ultra-rich Chinatown (1974) patriarch, delivering lengthy speeches that are so wordy and mindlessly hyperbolic that not even Huston can sound like he half-believes them. The same problem besets a baby-faced Jeff Bridges in the dimwitted hero slot, though Anthony Perkins, in a more marginal part, manages to incorporate the faint suggestion that he knows that his speeches are blather. The result of such flippant and undernourished overreach is that the issue of who killed JFK and why is made to seem almost as inconsequential as this movie. The only ideological area in which Richert’s film shows any advancement over The Manchurian Candidate is its mild undercutting of the earlier film’s JFK/James Bond-style ’60s sexism: Belinda Bauer, in what at first seems to be a standard-issue girlfriend role that gradually becomes somewhat more interesting, is allowed to outsmart, outflank, and overwhelm Bridges’ bemused character as long as she’s allowed to remain on screen, before her character evaporates into hazy and lazy suppositions made by Perkins and Huston.

***

The first and (so far) only time I’ve thoroughly enjoyed a Luc Besson movie without blanching or being distracted was when I recently stumbled upon the Universal DVD of Lucy (2014), an enjoyably absurd metaphysical SF thriller about mental expansion whose main calling card, apart from its special effects, is Scarlett Johansson — who must have been the main reason, apart from the sale price, why I picked up this release. (A comparable erotic reflex, tied to both ’50s MGM starlet Elaine Stewart and the proud emblazoning of “CinemaScope” on the cover, goaded me into ordering a used Universal DVD of The Tattered Dress [1957] from Amazon, which turned out to be panned-and-scanned — proof that these sort of impulse purchases can be fraught with peril.) I even got a kick out of the DVD extra, “Cerebral Capacity: The True Science of Lucy,” hosted by Johansson’s co-star Morgan Freeman, in which Besson tries to justify all the silliness intellectually.

***

Speaking of erotic motivations: in a recent article on The Outline about erotic thrillers directed by women, Abbey Bender — after citing David Denby’s dismissal and my partial defense of Jane Campion’s In the Cut (2003) — remarks that, “With its somewhat dour palette (unlike many erotic thrillers, the film isn’t very ‘fun’), In the Cut is more of an object to be studied than enjoyed.” Feeling tarnished (along with Campion) by Bender’s bad grammar, I hasten to add that my own liking for this movie, as with Lucy, has nothing to do with academic enlightenment and is strictly and exclusively a matter of fun (without scare quotes, and speaking in terms of both erotics and aesthetics, at least insofar as anyone can separate these two forms of sexiness). It was certainly the prospect of fun that recently led me to order the Sony Pictures “Uncut Director’s Edition” DVD of In the Cut for $9.94 and take a second look, and I was amply rewarded — at least whenever I felt that the movie was coasting along on its own eccentric and politically incorrect juices and not dutifully retreating or collapsing into routine genre reflexes (of the whodunit and serial-killer kind), as it finally does in its closing stretches. For me, those reflexes are the dourest erotic-thriller palette of them all, at least when it comes to the talents of someone like Campion. (Treating In the Cut in terms of its genre is a bit like evaluating the director’s earlier Sweetie [1989] as a rom-com — which may be why Bender finds it dour.) I also find it funny that Denby grounds most of his dislike of the film in the purportedly “unbelievable” nature of the story and heroine — presumably unlike the story and heroine of Basic Instinct (1992), which can readily adjust their own purposes to the demands of genre — and in his finding some of the settings in Campion’s fantasy far too sordid for his uptown taste. Having only recently experienced the lamentable groupthink of American reviewers explaining why they disapprove of and dislike Joker (as if to teach Lucrecia Martel’s Venice jury a proper lesson in how to receive their received ideas), I can only regret the impulses that chide Campion for not being a conventional (i.e., puritanical) feminist while ignoring Polanski whenever he refuses to make movies the way a proven sex offender should. Forgive me for pointing this out, but I think what keeps these filmmakers so elusive and hard to pigeonhole is precisely what keeps them worthy of our interest.

***

There are two features called A Bigger Splash, each one named after the same David Hockney painting. I like both of them, although I like the first one—a fictional/ nonfictional study of Hockney’s love life and work, made in 1974 and directed and co-written by Jack Hazan — a whole lot more than the less Hockney-related 2015 thriller directed by Luca Guadagnino, even though the latter has the good taste to star Tilda Swinton. The Guadagnino film is apparently the only one available on Blu-ray, but the Hazan certainly should be; I ordered it on DVD, but it still hadn’t reached me before my deadline.

The Hazan film — which I saw a lovely restoration of in Bologna last summer, after first seeing it in London when I was living there in the 1970s — is a game changer: one of the most beautiful fusions of the art of painting and the art of cinema that I know, and one of the earliest and freest depictions of a gay subculture in film that I’ve seen. I’m rather annoyed with myself for not having included it on my ten-best lists for either 1973 or 1974 (both submitted to the Village Voice via Andy Sarris), but, of course, that was an unusually rich period that also encompassed the belated U.S. release of Tati’s PlayTime, Rivette’s Out 1: Spectre and Céline et Julie vont en bateau, the even more belated Western appearance of Kinugasa Teinosuke’s 1926 A Page of Madness, Truffaut’s Day for Night, Siegel’s Charley Varrick, Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac, Fassbinder’s Martha, Altman’s California Split, Coppola’s The Conversation, Resnais’ Stavisky…, Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, Hellman’s Cockfighter, and, to conclude with a trio of lesser-known items, Marcel Hanoun’s L’Automne, Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Who is Beta?, and James B. Harris’ Some Call it Loving. (The only item on those two Voice lists that I no longer remember is Georges Franju’s The Man without a Face [sic], which must have been a tentative English title for Nuits rouges, eventually released in the US in an English-dubbed version as Shadowman. Clearly, it was far less memorable than Hazan’s gorgeous masterpiece; in retrospect, I tend to believe that Franju’s greatness lasted only as long as he filmed in black and white.) In any case, seeing the reviews of Hazan’s film on Amazon, many of them split between enthusiastic endorsements and illiterate tantrums brought on by its originality, I assume it will always be controversial.

***

Beautifully restored by Ross Lipman, Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1984) — which was scripted and shot by Charles Burnett, who brought along members of his own family to join the cast, along with Kaycee Moore from his Killer of Sheep (1978) — is out in a superb Milestone DVD, which also includes Woodberry’s touching short The Pocketbook (1980) and Lipman’s interview with Woodberry about his collaboration with Burnett. James Naremore’s 2017 monograph Charles Burnett: A Cinema of Symbolic Knowledge devotes seven pages to this wonderful feature — which was memorably excerpted in the closing stretches of Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), and selected for the National Film Registry ten years later — and I’m glad that Naremore’s discussion focuses largely on troubled issues of masculine identity, which the film remains gently and subtly responsive to throughout.

Postscript: in the interests of full transparency, I’m delighted to report that Grasshopper Films’ two-disc Blu-ray and DVD editions of Patrick Wang’s two-part A Bread Factory — reviewed by Michael Sicinski in Cinema Scope 78, and probably my favourite movie of 2018 — include my 51-minute interview with Wang in Chicago last April, a 23-minute feature by Wang called Filming “Hecuba”, a music video, a trailer, and optional English, French, German, Portuguese, Chinese, and Korean subtitles.