From the Chicago Reader (April 24, 1998). I’m not sure why, but this is one of my long reviews for the Reader that appears to have disappeared from their web site. — J.R.

I’ve seen Ross McElwee’s documentary Six o’Clock News (1996) twice, on video about eight months apart, and each time there was a moment roughly halfway through when I felt that he was finally about to turn a corner as a filmmaker. This Boston-based North Carolinian is known as an independent autobiographer, yet what I’ve come to appreciate most in his work are those moments when autobiography leads him away from himself to other people.

His old friend and former teacher Charleen, for instance, is a far more vibrant presence and far wiser commentator than he is in Charleen (1978), Sherman’s March (1986), and Time Indefinite (1993). Of course, McElwee’s personality and style of filmmaking are what makes a Charleen possible, filmically if not existentially, so extracting her from his works would be as difficult as removing Falstaff from Shakespeare or Humphrey Bogart from the cozy miniature environments of To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. Yet the points at which McElwee’s appreciation of Charleen fuses with mine, turning him into a vehicle rather than a destination, are the moments when he functions as a journalist.

As a chronicler of the new south in all its baroque craziness and contradictory charm, McElwee’s persona in Sherman’s March was a necessary tool, but as a subject in its own right I doubt it could have sustained 155 minutes. This isn’t because McElwee lacks baroque craziness and contradictory charm, but because he tends to wear these attributes on his sleeve as proof of his universality. If Time Indefinite — which charts the death of his father, his marriage, and the birth of his son — seemed to reveal McElwee as a lightweight after the endless suggestiveness of Sherman’s March, it might have been because the closer his rambling methodology gets to ordinary experience the less he has to say. If his principal bid for our interest is how homespun he is, it would be more fun to listen to his eccentric neighbors or wait for Charleen to come back.

Six o’Clock News begins with McElwee’s son Adrian at the age of one week and ends a little past his fourth birthday. In between are countless TV news reports of human disasters and ruminations from McElwee about what they mean, a few desultory cross-country trips tracking down victims of some of those disasters, and two significant appearances by Charleen — toward the beginning of the film she goes to find out whether Hurricane Hugo left her house standing, and at the end she triumphantly greets her first grandchild.

Some of the ruminations put me in mind of the semicrazed letters and notations scribbled by Moses Herzog in Saul Bellow’s novel, one of which is an apt, unattributed saying from the 18th century: “Grief, Sir, is a species of idleness.” They hover on the edge of profundity, the way practically all ruminations on human disasters do, barely touching on issues of religious faith, meaning, coherence, and mortality. But after a while, it becomes apparent that the grief belongs only to the victims and the idleness belongs only to McElwee in search of material — their grief is a species of his idleness. Like Herzog, he doesn’t know what to do, so he turns on the TV — and the news on TV gets him sufficiently involved with the world to make a few gestures. Whereas Herzog writes a letter, McElwee tracks down, befriends, and films a fresh disaster victim, then moves on — another chapter in his autobiography completed.

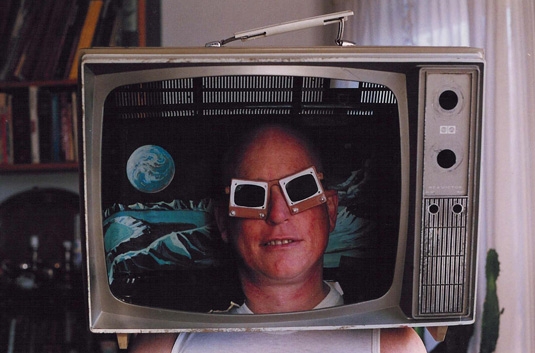

Yet there were also moments when I forgot about the autobiography, when the people McElwee met took over. There’s his Boston landlord, Barry, who owns ten TV sets and obsessively collects favorite shows. And there’s Stephen Im, a Korean businessman in the deep south whose wife was slain for the $44.90 in her cash register. It was Im who made me hopeful that McElwee was finally phasing himself out. Im and Barry both suggest grand subjects that entire documentary features could be built around.

But three disasters later McElwee is back in the everyday muddle of his own life and ruminations about an offer to go to Hollywood and direct a pseudodocumentary for Miramax. The problem may be the scourge of the camera itself: Im is a touching and fascinating individual whose quirky traits — such as listening to heavy metal on his car radio with the volume turned low — are downright novelistic. But when he appears on camera with his new Korean wife, who doesn’t speak a word of English, and proudly recounts in English all the secrets he’s been keeping from her, it starts to become clear that McElwee’s camera is too aggressive and transformative to serve as an impartial witness. (Im had previously remarked that half of him hates America and half of him loves it; which half, I wonder, causes him to betray his new wife so effortlessly?) And if the ultimate function of these people is to fill in part of McElwee’s design, it becomes increasingly hard to understand them independent of that agenda.

The funny thing about McElwee’s obsession with the six o’clock news is that it echoes his distaste for making Hollywood fiction features. Every time he encounters a TV news crew — either on his travels to disaster sites or when he’s interviewed by a Boston crew as a quirky filmmaker — his irritation is palpable, because again and again these crews are competing with his own efforts as a documentary filmmaker, figuratively as well as literally, just as Hollywood features do. He even underscores the point when he shows the Boston crew restaging their entrance into his apartment twice, something he wouldn’t do himself, and when he recounts the abrupt end of his relationship with Salvador Pena, a victim of the Los Angeles earthquake, after the TV series Rescue 911 promises to fly this fellow’s family in from El Salvador if he grants them exclusive rights to his tragedy. Earlier McElwee drives all night to Phoenix, Arizona, deliberately following a storm front, but he’s frustrated when the storm keeps him shut up all day in his motel room watching the TV reports. And he’s frustrated again when he visits a ravaged mobile-home park where a series of rival camera crews preempts his exclusive interviews and reduces him to filming the crews instead.

Chase down a disaster victim in this film and what you ultimately get is a profession of religious beliefs. Im decides he believes in God but that God is “out of control” — a confession he chooses to make offscreen, unlike his confession of the secrets about his wealth he’s kept from his wife. Pena, even more devout, believes that God was testing him by trapping him for eight hours inside a crumbled parking facility in pain so acute that he tried to strangle himself before he was rescued. (A trust fund inspired by the TV news report yielded $1,100 — small change compared with the $200,000 John Wayne Bobbitt reportedly got from well-wishers.)

But these and other victims in the film are generally too busy attending to their lives to ruminate much on the meaning of their fates, so McElwee has to wait around for them to deliver these conclusions on camera, befriending them in the process. He even accompanies Im and Pena to church, and when he goes with Pena and finds himself observing a praying woman he doesn’t know, I start wondering if his obtrusiveness is any different from that of the TV crews. I’m reminded of Orson Welles’s suggestion in an interview that filming the act of prayer was potentially as obscene as filming the act of sex; here it functions as a mechanism for pumping meaning into a movie that has nothing to do with the woman, which makes it feel immensely exploitative.

These are harsh words, but I don’t mean to question McElwee’s sincerity or good will. Cumulatively the anthology of news disasters carries a genuine philosophical weight, and some of his fact-finding missions took me places I’ve never been before. (Others land him and us in dead ends, but he’s honest enough to include those too.) But the moment a filmmaker commits to filming his own life, the issue of whether he’s shaping his life to shape his movie never goes away — and both film and life are at risk of being bent in the process.