Written for the Busan International Film Festival’s Korean Film retrospective catalogue, Fly High, Run Far: The Making of Korean Master IM Kwon-taek, Fall 2013. — J.R.

Preface

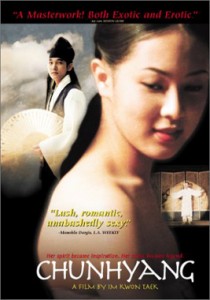

I can’t pretend to be familiar with Korean history in general and traditional Korean music in particular. But rather than attempt to disguise my ignorance with a handful of facts gleaned from superficial research, I prefer to approach Chunhyang (2000, 136 min.) in broader, more generalized, and less historical terms as a film confronting issues of representation relating to live performance as well as cinema, and the survival of relatively ancient forms of music and performance in the present.These are the issues that have drawn me to Chunhyang in the first place, despite an overall ignorance about Korean culture that extends to most of its cinema — including even most of the oeuvre of its most celebrated auteur, Im Kwon-taek.

I hope that this admission of my lack of knowledge and innocence can be regarded as a form of clarification and honesty rather than as an expression of arrogance. My theoretical assumption is that the most common form of journalistic bluff regarding such matters — conveying an unearned and unwarranted stance of authority, typically justified through a series of lazy intellectual shortcuts and/or appropriations (such as, for example, describing pansori as some Korean variant of the American blues) — is ultimately more imperialistic in effect than any honest admission of cultural ignorance.

At the same time. because I fully believe that the most important innovations in art, especially those with some relation to the avant-garde, generally come about through a drive to express formerly unexpressed and otherwise inexpressible content, motivated most often by a sense of personal necessity, I fully acknowledge the likelihood that some of the motivations underlying Im Kwon-taek’s Chunhyang are deeply personal — a notion which is spelled out in some detail by Chung Sung-ill in his book about the filmmaker:

[Among]…the four representative pansori musicals in Korea, Chunhyang-jeon is the most famous one. Behind the artful verse, humor, and satire in pansori are Korean tears and laughter. However, we must not overlook one point. This story is staged in the southwestern part of Korea, in Namwon. In other words, no matter how many different versions there are, the background of the story, Namwon in Jeolla Province, doesn’t change. For Im, shooting Chunhyang meant shooting the sounds of his own hometown, proudly showing off his hometown in his return. (Just like Lee Mong-ryong who comes back as a king’s undercover agent and saves Chunhyang from prison.) …By stating that Chunhyang is concentrating on formalities, this actually means Im is desperately looking for the way to his hometown.

According to his words, Chunhyang is his answer to Sopyonje. While he was making Sopyonje, he listened to the complete version of Chunhyang-jeon, then decided that his ultimate goal was to put the deep emotions of the pansori musical itself into a movie. If the artistic features of pansori can be illustrated through the system and form, movement structure, and the graph of sensibility of a movie, then the products of the modern West and Korean cultural heritage can finally be reconciled harmoniously. This is to embrace and overlap two very different forms of art with two different histories without any common denominators. Could these two make one world by co-existing with the peculiarity of each other’s powers? Im questions over and over again in Chunhyang how he can bend the movie into pansori structure(reconstruction of mise-en-scène), straighten curves (editing that follows the sound), then bend it again (very brave omission), and produce it on one stage (story and the musical). (1)

All this suggests that the issues of representation that crop up repeatedly in the film, the focus of my following remarks (which are restricted mostly to examples drawn from the film’s first half), are not merely academic concerns but pressing existential questions and practical strategies resulting from them. They seem to point to a fundamental anxiety about translating from one art form to another as well as to an onrush of creative strategies for attempting both to assuage and to benefit from that anxiety. The frequency of the camera movements, which are nearly always expressive rather than simply expositional, is emblematic of this restlessness and uncertainty, and the expressiveness, though mostly tied to the viewpoint of Lee Mong-ryong (and including subjective camera angles), occasionally encompasses other viewpoints as well — including Chunhyang’s, when the offscreen pansori performance privileges her feelings, but also, much later and more implicitly, the viewpoint of her mother, when Lee Mong-ryong, dressed as a beggar,arrives at their home.

1

Chunhyang begins, in long shot, with a pansori performance in a dark, abstract space that appears to be an auditorium or concert stage, judging from the looks and gestures of the singer and main performer (which seem to be aimed alternately at the drummer and in the same general direction as the camera), but without any visible or audible sign of any audience.

We cut to an overhead descending crane shot over a contemporary urban street alongside a street sign pointing with an arrow towards Chõngdong Theater. Several teenagers are seen stepping out of a blue car in front of this theater, where a boy and girl in the group who linger behind the others have the following exchange:

Boy: “Traditional music is good and all, but how are we going to stand it for five hours?”

Girl: “I think there is a reason why we were told to watch it.”

Boy: “What reason? It’s the same old tale of Chunhyang.”

Already, two important parameters are being established: (a) Practically anyone who has started watching the film will already know that it runs for 136 minutes, not for five hours (or 300 minutes), meaning that an important distinction between a pansori performance of Chunhyang and this film entitled Chunhyang is already being made. (b) The primary audience being addressed by the film is Korean, i.e. an audience that will be able to identify and recognize what “the same old tale of Chunhyang” means.

As I’ve already suggested, these parameters both attest to a certain anxiety about translating an ancient art and practice into the norms of contemporary commercial cinema, highlighting a discrepancy that is equally apparent in the synopsis accorded to the film in Chung Sung-ill’s book. (2) Apart from a short footnote, this synopsis seems to equate the film with the traditional tale that serves as the basis for a corresponding pansori performance–one that is referenced and excerpted but not actually reproduced in any comprehensive fashion. And the footnote mentions the pansori performer Cho Sang-hyun—credited with furnishing the film’s “original idea,” but not as an actor or performer—beginning and ending the film with a performance of “Sa-rang-ga, a love song,” with his voice taking “the role of narration” in between, but it makes no allusion to the teenage spectators that function initially as our surrogates.Thus, paradoxically, what I would identify as the major creative and analytical contribution of the film, which involves the cinematic “translation” of the tale and takes many shifting forms, is virtually elided from the synopsis.

It’s worth adding that the performance of Sa-rang-ga will return a little over half an hour later, offscreen, to accompany a scene of lovemaking and erotic cavorting between Lee Mong-ryong and Chunhyang. Here, again, the visual strategies of representation are restlessly kaleidoscopic; the shifting etiquette of exposure and concealment as the characters move on and offscreen, periodically moving behind walls and screens, is adroitly echoed and counterpointed by the revealing or masking movements of the camera, so that soon after their nudity is discreetly shown on the right side of the frame, the camera moves briefly away from them to the left, as if out of modesty. (A little later, during a second sequence of this kind, we see their bodies retreat into darkness.)

When the film’s prologue follows the group of teenagers into the theater lobby and then into the auditorium to take their seats, we learn further that their attendance at this event is required, apparently by a school assignment (“Hey, isn’t anyone going to buy the pamphlet? We’re going to need it for the report”) and that many of them are expecting to be bored; they even make jokes about taking turns at falling asleep. One boy even starts to leave, hoping to crib whatever information he needs for the report from the Internet, until a girl gets him to sit back down and “Hang in there.”

A long shot in reverse angle shows the two pansori performers arrive on the stage to applause. This leads us to question the precise place and time of the preceding pansori performance that we saw at the film’s opening, which seems to have had the same two performers, but with a different backdrop and (apparently) occurring on a different, unspecified occasion. It’s almost as if the first performance we see qualifies generically as“pansori” while the second qualifies as a particular and specific instance of it—and the second is prefaced by the main performer’s announcement that it will run for five hours, already distinguishing it once again from the film that we’re watching.He also mentions that there will be two intermissions, makes a joke about the trips to the bathroom that this will permit, and asks for the audience’s “encouragement” of his live performance — three more factors separating this performance from the film we’re watching and pointing towards an assumption that the film’s spectators, like the teenagers in the auditorium, wouldn’t welcome a classic five-hour pansori performance, meaning that an abridgement as well as a cinematic translation has to be fashioned as some sort of evocation and substitute for that experience.

Finally, continuing in his speaking voice, Cho introduces the scene, period, and hero (Lee Mong-ryong) of the story while the camera is seen approaching the latter in separate stages and shots. A dialogue between Mong-ryong and his servant, Bang-ja, follows, establishing that he wants to go for a ride after being cooped up for months; there’s a cut to him climbing onto his horse, at which point Cho’s sung narration begins.

2

Much of the film’s dynamism can be felt in the almost constantly shifting relation between word and image in the brief passage that immediately follows, which I have tried to annotate in a rudimentary fashion (with a few slight adjustments to the English subtitles to make them more grammatically consistent with one another):

“He mounts the horse” (close-up of Mong-ryong’s foot entering his horse’s stirrup) “and Bang-ja leads the way” (medium shot of Mong-ryong on his horse in profile being led by Bang-ja –a reverse angle of the previous shot). “As he leaves the South Gate, [with] a fan shaped like a crane’s yellow wing “ (an extreme long shot of Mong-ryong, framed more frontally on his horse as he moves towards the camera, surrounded on all sides by other figures), “he flips it open to block the sun” (a close-up of Mong-ryong in profile opening his fan to block the sunlight) “as he travels down the South Road. The breezy dust from each trot” (a long shot following Mong-ryong from behind, again surrounded by other figures; the fan, barely visible from this angle, is no longer shielding his face or parallel with it, but held somewhat lower; and no dust or breeze is visible) “flutters in the air with the scent of peach flowers…” (a long shot in motion of Mong-ryong riding on his horse in profile, moving from right to left).

Although the two close-ups approach a simple equivalence between narration and what’s being shown (Mong-ryong mounting his horse or flipping open his fan), the medium shots and long shots show an increasing disparity, not only in what they neglect to show or reveal (“the breezy dust,” “the scent of peach flowers”), but also in the wealth of visual details that are included relating to the setting, landscape, and multiple surrounding figures but are missing from the narration. Many of these details continually threaten to overwhelm the narrative thread–and, indeed, would probably overwhelm this thread if they didn’t have the clarifying contexts of the narration and the two close-ups. Thus they might be said to highlight the overall disparity between the linear thrust and forward movement of the words and music on the one hand and the nonlinear, nonnarrative, and painterly dispersal of the visual details on the other.In short, the shotgun marriage being staged by Im between pansori and cinema shifts from moments of apparent fusion to other moments when they seem to be miles apart, and the choreography of their interaction becomes central to the film’s dynamic poetry.

3

Chung notes that Im spent four months concentrating on “the scene where Bang-ja is ordered by Mong-ryong to go to Chunhyang to inform her of Mong-ryong’s feelings. He shot it over and over again,” and “didn’t just edit to fit the sounds, but…cut the shots to fit the rhythm and then [filmed each] shot with [a different lense],” with corresponding changes in focus and/or forward and reverse zooms designed to match Bang-ja’s movements. (3) This section reaches a sort of climax when Chunhyang delivers a proverb as a message to Mong-ryong that appears onscreen as a Korean subtitle: “The wild geese desire the sea, the crabs desire their holes, and a butterfly desires a flower.” Later on, during the second sequence that celebrates the couple’s erotic discovery of one another, a single Korean word, apparently meaning “one,” will also appear onscreen, and in both cases, it would seem that the prestige of literary poetry briefly trumps the prestige of pansori performance.

4

I’d like to conclude with what may be Chunhyang’s most complicated stretch in terms of narration, point-of-view, and mise-en-scène, all of which become interactive and at times almost interchangeable, approximately 90 minutes into the film. It begins with the on-screen singing narration of Bang-la, carrying Chunhyang’s letter to Lee; after he recognizes Lee in his beggar clothes and gives him the letter, the narration is taken over by Chunhyang’s voice offscreen, reciting her letter to offscreen musical accompaniment. Then the pansori singer takes over: “When the sun is about to set…” (over a shot of the sunset) “he arrives in front of Chunhyang’s home…” (a long shot of the house at night, with a slow zoom forward) “In the back of the garden is a silent cry.”(The same forward zoom continues.) “He’s drawn to the sound” (in another shot, the camera moves from right to left across the side of the house) “to take a closer look” (the same camera movement continues).

Complicating the above sequence, apart from the anomaly of Lee “hearing” a “silent cry,” is the fact that the shots of the house appear to be partially drawn and partially photographed, and the additional fact that the camera movements along the side of the house suggest without actually replicating Lee’s point of view as he moves in that direction. Then we hear that Lee sees Chunhyang’s mother “at a small altar in the backyard…with lit candles…and a bowl of clean water” at almost precisely the same moment that we see these details, but a much closer shot of the mother in the foreground that moves forward and past her to the bowl and candles suggests a switch to her viewpoint, complicated by a cut to an overhead shot of her praying that slowly pans down while the pansori singer then begins to speak for the mother: “I pray…to the gods of heaven and earth…Please come and help me.” This becomes in turn a prayer that Lee come to her assistance, at which point we cut to a shot in which the camera approaches Lee himself, speaking to her. Over the space of a few moments, the characters and the story, objectivity and subjectivity, and pansori and cinema finally speak with the same collective voice.

End Notes

- Translated into English by Han-Na-ra, Seoul: Korean Film Council, 2006, 49-50.

- Ibid., 142-145.

- Ibid., p. 50.