From the Chicago Reader (April 16, 2004). As much as I share my colleagues’ admiration [in 2012] for Jafar Panahi’s This is Not a Film, I must confess that I find it both depressing and somewhat insulting to Panahi that this is receiving more attention and praise in some quarters than his full-fledged films ever did, including such masterpieces as The White Balloon, The Circle, and Crimson Gold (not to mention Panahi’s more inventive and fruitful 2013 Closed Curtain, made under the same constraints as This is Not a Film). Which is why it seems worth reviving my review of the latter film. — J.R.

Crimson Gold **** (Masterpiece) Directed by Jafar Panahi Written by Abbas Kiarostami With Hussein Emadeddin, Kamyar Sheissi, Azita Rayeji, Shahram Vaziri, Ehsan Amani, and Pourang Nakhayi.

“War President” is an image. It is not a textual statement or rhetorical argument. An image is like an empty room and any message that one reads in that room necessarily came in the baggage one carried when one walked in the door. If I made an image of George Washington composed of images of the American dead from the revolution, would viewers likely take that image as an indictment of Washington? I submit that they would not. It would be viewed as a monument to the dead and a celebration of a great leader, a somewhat maudlin monument maybe but surely not offensive. The fact that “War President” is not viewed [in] such a manner is not due to any intrinsic power of “War President” but lies somewhere else. — posted by the creator of the War President mosaic (matrixmasters.com/world/usnews/WarPresidentMosaicStory.html)

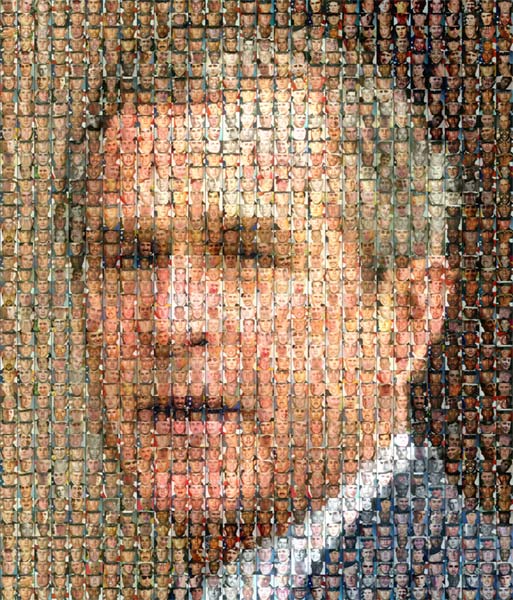

Jafar Panahi’s fourth feature, scripted by Abbas Kiarostami, tied with Spike Lee’s 25th Hour as my favorite film of last year. I saw Crimson Gold twice at the Toronto film festival last September and had the impression that despite its simplicity and directness it had more treasures to impart — treasures that had as much to do with the state of the world as with the state of Iran. Having recently seen the film again, I find that the simplicity remains and the resonance has grown. Like 25th Hour, this Iranian feature has something important to say about the way we all live, though it’s not remotely didactic. (The only exception is a single, seemingly extraneous early scene featuring one of Kiarostami’s characteristic sages in residence — like the taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us — who turns up in a cafe to expound wittily, grandly, and unnecessarily on the moral nuances of stealing to the hero and his best friend, who has just snatched a purse.) Panahi is a seeker more than a finder, and what he has to say about the modern world in general and contemporary Iran in particular can’t be reduced to a simple message. Like War President, a portrait of George W. Bush made up of hundreds of small photos of American soldiers killed in Iraq, it’s an image rather than a rhetorical argument — another empty room whose message arrives in one’s own baggage.

Crimson Gold was inspired by a newspaper story Kiarostami read about a pizza deliveryman in Tehran who held up a jewelry store, shot the owner, and then killed himself. Some critics have called the story quintessentially American, but in a shrinking world this premise sounds dubious. Kiarostami’s script, the best he’s written to date for another director, attempts to discover what drove the man — beginning with the pivotal events as seen from a surveillance camera inside the jewelry store before leaping without transition to a few prior events involving the deliveryman (who has the same name as the man playing him, Hussein Emadeddin), his best friend and coworker, Ali (Kamyar Sheissi), and Ali’s sister (Azita Rayeji), to whom Hussein is engaged.

The tentative and partial answer to the question has to do with class humiliation — Hussein and Ali are both humiliated at the jewelry store, where later they, along with Ali’s sister, are humiliated again — and with a form of petty harassment that’s implicitly seen as a normal part of contemporary urban existence. The humiliation and harassment might be viewed as two versions of the same thing, stemming from social paranoia and institutional indifference to the suffering of ordinary people — which certainly aren’t limited to Iran.

No Iranian feature I’ve seen, including any of Kiarostami’s, has better caught the look and feel of Tehran (which I visited for a week in 2000) — the pollution, the traffic congestion, the class distinction that comes with living on the mountain in the city’s north. But the greater achievement of Crimson Gold is to pinpoint an everyday experience that’s universal, and in this it surpasses Kiarostami’s most recent feature, 10, which is limited by its almost exclusively middle-class vantage point and its far less pointed and insightful social critique. The everyday harassment experienced by Hussein is spelled out in a long sequence roughly halfway through the film, during the second of three pizza deliveries, or attempted deliveries. During the first he’s recognized by a former fellow soldier in the Iran-Iraq war, though medication he takes for injuries he suffered in a chemical attack have changed his appearance and slowed him down; during the third delivery he’s invited into a palatial penthouse suite by a wealthy Iranian (who also has the same name as the man playing him, Pourang Nakhayi). The man recently moved back from the U.S. and invites him to share the pizza because the woman he ordered it for has left. During the second delivery attempt policemen and a teenage soldier with a rifle stand outside an apartment building where a party’s being held on the second floor and refuse to let Hussein take pizzas to the third floor. We eventually learn that they want to arrest people as they leave the party — for drinking, dancing, and indulging in improper behavior between the sexes — and they’re afraid Hussein will warn the partygoers. They won’t even let him borrow a cell phone to call his boss about what to do, saying he might call and warn someone at the party. So he’s forced to stand in the street watching a party he’d never be able to attend; we see the partygoers only in silhouette through the window, the closest we get to any middle-class life in the film. Finally he offers the pizzas to the cops and soldier. It’s an absurd form of everyday, paranoid bureaucratic intimidation that called to mind something I witnessed a few days ago at O’Hare, where new rules now force almost all foreigners to be fingerprinted before entering the U.S. The lines were longer and slower than I’ve ever seen in any airport, though as a U.S. citizen I didn’t have to wait as long. I had to wonder how irritating, insulting, and humiliating thousands of visitors every day could possibly make this country any safer. In 2000 Panahi himself was shackled and expelled for refusing to be fingerprinted while changing planes in New York en route to South America from Hong Kong, and to further protest the fingerprinting of all Iranians who come here, he now refuses to enter this country. Ironically he’s accused of being an American agent by some Iranian mullahs because of the implied social criticism in the party scene described above — one reason Crimson Gold is banned in Iran. This kind of provincial cluelessness and universal mistrust must ultimately make the whole world kin.

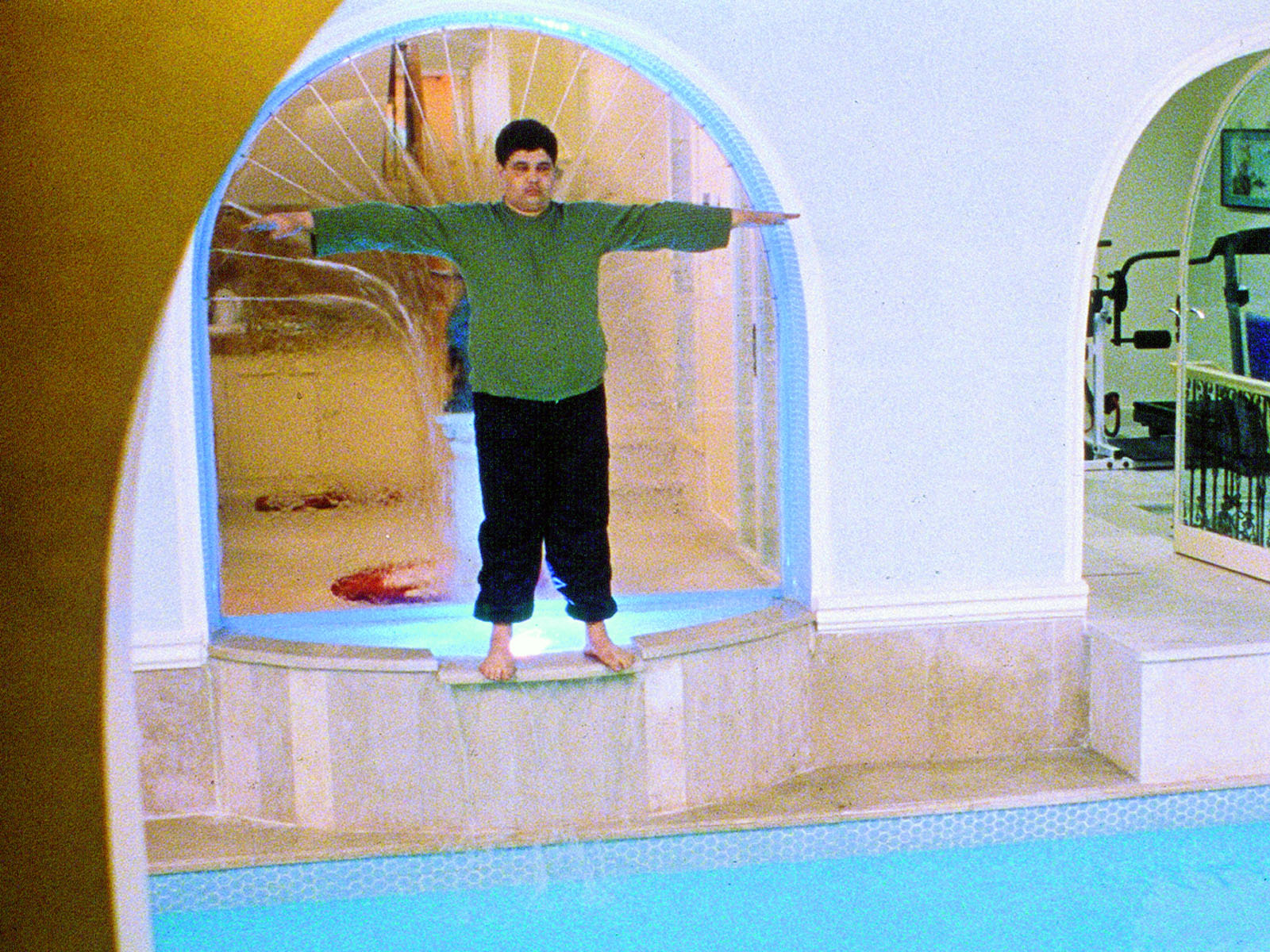

“Inequality exists in every country of the world,” Panahi told critic David Walsh last fall. “But a certain point can be reached [when] the gap between poor and rich gets bigger, and that’s how it is right now.” He’s referring to Iran, but he could be speaking about many other countries, including America. Unlike Panahi’s first three features — The White Balloon, The Mirror, The Circle — Crimson Gold doesn’t concentrate on female characters or the inequality they typically suffer from. Yet Hussein’s fiancee is as good an illustration of the passive aggression of some Iranian women as anything in the documentary Divorce Iranian Style, and the misogynistic tirades of Pourang Nakhayi about his date say as much about Iranian sexism as anything in The Circle — though again neither of these details is made to seem exclusively Iranian. There’s no Marxist caricature of the rich to be found here. If Panahi had a particular thesis about class to sell, he would have made Nakhayi as snooty toward Hussein as the jewelry-store owner. But Nakhayi, for all his neurotic self-absorption, treats him hospitably and as a social equal, and Hussein’s visit to Nakhayi’s penthouse is the only time we see him relax. This sequence immediately precedes the abortive jewelry-store robbery — a juxtaposition that’s the film’s most mysterious move. In the interview with Walsh, Panahi says that Hussein’s lack of interest in stealing from Nakhayi shows that he isn’t a thief. Yet are we to conclude that Hussein’s seemingly idyllic night in the penthouse motivates his criminal behavior by showing him what he can’t have? The film refuses to say, though I suppose one could conclude that Nakhayi’s friendliness only underlines the impossibility of Hussein’s ever joining the classes above his own.

In Toronto critic Robin Wood compared this sequence with the scenes involving the Tramp and the millionaire in Chaplin’s City Lights. I think that most of Crimson Gold and all of its major characters verge on being comic. Hussein is big and slow, Ali small and manic, and the two often resemble a slapstick duo like Laurel and Hardy. The teenage soldier is something of a humorous hayseed, and the scene in the penthouse, climaxing in a weirdly hilarious dive into a swimming pool, gets much of its comic energy from Nakhayi’s Woody Allen-ish neuroses and nonstop patter. Surely it’s just a coincidence, but the only other film with the title Crimson Gold that I came across on the Internet Movie Database is a 1923 comic western. If American comedy lurks behind the film’s deceptive style, another relevant, even more unexpected reference might be Taxi Driver — a Taxi Driver without the stylistic lushness of Martin Scorsese’s imagery, Bernard Herrmann’s romantic and portentous score, or Robert De Niro’s charismatic lead performance. Yet Crimson Gold may be just as definitive a portrait of urban isolation and the despair of an alienated war veteran — consider the brief scene when Hussein returns to his claustrophobic flat and lies down on his bed fully clothed, too indifferent to turn on any lights. Indeed, it’s the singular presence of Hussein Emadeddin — a nonprofessional like all the other actors Panahi has used in his films — that gives the film much of its soul and mystery. An overweight, deadpan, medicated, real-life pizza deliveryman and real-life Iran-Iraq war veteran, he’s also a paranoid schizophrenic — something Panahi has implied he wasn’t fully aware of when he cast him in the part. Reportedly this made the film’s shooting a nightmare for everyone involved, including Emadeddin, though it’s impossible to imagine anyone else in the role. Maybe this is because the institutional paranoia that leads to all of his character’s everyday humiliations and frustrations, which he winds up reflecting and projecting, is a crucial part of the film’s texture — that is to say, of its image, not its statement or argument.