From the Chicago Reader (August 6, 2004). — J.R.

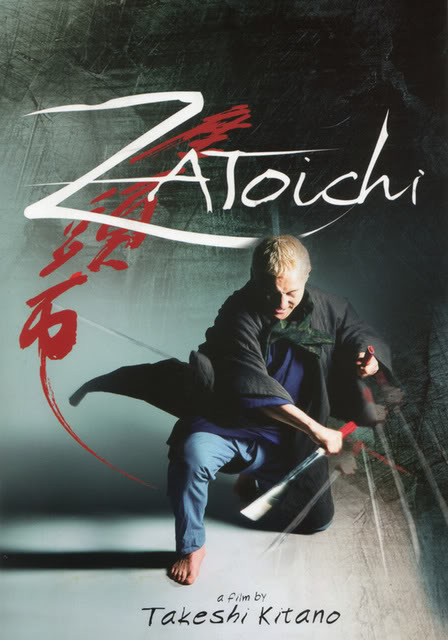

The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Takeshi Kitano

With “Beat” Takeshi [Kitano], Tadanobu Asano, Michiyo Ookusu, Yui Natsukawa, and Gadarukaru Taka.

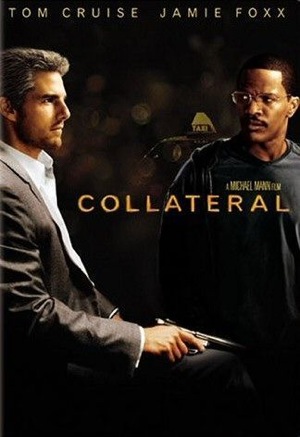

Collateral

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Michael Mann

Written by Stuart Beattie

With Tom Cruise, Jamie Foxx, Jada Pinkett Smith, Mark Ruffalo, Peter Berg, Javier Bardem, Bruce McGill, and Irma P. Hall.

What do Takeshi Kitano’s Zatoichi and Michael Mann’s Collateral, both opening this week, have in common? Judging by what some of my colleagues have been saying, they’re both effective action movies directed by talented genre specialists. But I would argue that this description applies only to Collateral.

Although Mann stretched himself somewhat with Ali, The Last of the Mohicans, and The Insider, he’s first and foremost a maker of adroit crime thrillers: Thief, Manhunter, Heat, and now Collateral. Kitano, on the other hand, is actually an adventurous director of art movies who periodically defaults to the crime genre in order to finance his other projects. In this respect he resembles Clint Eastwood, who, since emerging as an auteur in his own right, has alternated between making action movies for the studio and art movies for himself. Like Eastwood, Kitano is himself a star — a celebrated comedian, talk-show host, game-show guest, and dramatic actor, frequently working under the pseudonym “Beat” Takeshi. Kitano also shares with Eastwood a certain skeptical impatience with the rules and customs of the thriller form, an attitude that lends the genre work of both an overripe quality that might be called decadence.

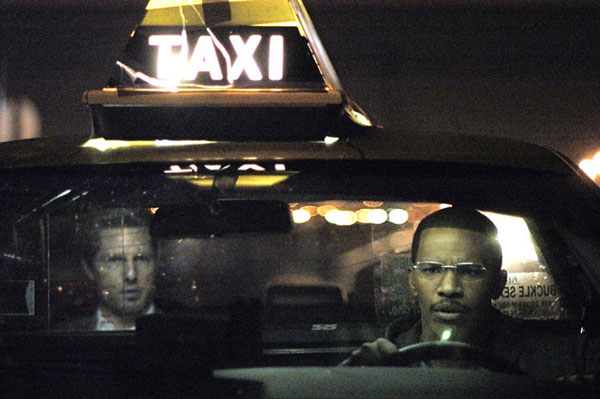

Mann, by contrast, betrays no such alienation from genre conventions. Collateral is a film that could have been made 50 years ago; it’s not hard to imagine a taut little black-and-white version of the story, which concerns a cabdriver named Max (Jamie Foxx) who’s forced at gunpoint to chauffeur a contract killer called Vincent (Tom Cruise) around Los Angeles as he tries to bump off five grand jury witnesses about to testify against a cartel of drug traffickers. Max, we discover, has dreams of establishing his own limo service, while Vincent is the product of a harsh institutional upbringing. If all this sounds familiar, it’s supposed to — even though Mann and screenwriter Stuart Beattie are skillful enough to make it seem relatively fresh and new. At the beginning of the film they deftly set up an incipient love interest between Max and one of his customers, a federal prosecutor (Jada Pinkett Smith); later they work her character back into the plot in a way that doesn’t seem unduly implausible.

The film’s realistic surface, essential to its thriller mechanics, is a world away from the fantasy atmosphere of Zatoichi, a parodic fable about a blind masseur who has a way with a sword. Considered in isolation from their narrative settings and their stylization, some of the stunts and action moves of Collateral are actually nearly as outlandish as those of Zatoichi — though both pictures are too engrossing to invite this kind of skepticism while you’re watching them.

The best thing Mann brings to his picture is a strong sense of time and place. The plot of Collateral unfolds in a single night, and Mann’s feeling for Los Angeles, always acute, gains in power and density as the killer and his captive driver move from the airport to downtown, then from Koreatown to South Union to Fountain to a jazz club in Leimert Park. In the wake of the first murder, Mann begins crosscutting to the investigations of a cop (Mark Ruffalo) in a way that complicates and intensifies the film’s meshing with the cityscape.

Tom Cruise is effectively cast against type as the assassin, and comedian Jamie Foxx also does well in an atypical dramatic part. Mann’s success with well-worn genre tropes goes hand in hand with his actor- and character-driven approach to storytelling, which provides a solid grounding for the picaresque detours and digressions of Collateral’s plot. The digressions, which range from a hospital visit to Max’s ailing mother (Irma P. Hall, virtually replaying her part in the Coens’ remake of The Ladykillers) to an anecdote about Miles Davis told in the jazz club, do as much to test and develop the lead characters’ personalities as to foster suspense.

For some time Kitano has been alternating regularly between crime films and more experimental projects. The commercially and critically unsuccessful Kikujiro (1999), a weirdly mannerist road movie in which Kitano plays an offbeat father figure to an abandoned boy searching for his mother, was followed by Brother (2000), a slam-bang yakuza-versus-Mafia drama set in Los Angeles. Next came the difficult and daring Dolls (2002), a complex of interlocking love stories for which Kitano stayed behind the camera.

Unlike Eastwood, Kitano writes as well as directs, and one thematic constant in his work is the idea of arrested development, expressed most nakedly in Kikujiro. This distinguishes his brand of fantasy from the two Kill Bills and the two Spider-Mans, which strive to show some signs of “maturity” in their adolescent-fantasy concerns and never look more childish than when they do. (Similarly, commentators attempting to discuss such films from a grown-up vantage point risk falling into the same trap.) In other words, Kitano usually seems to start from the premise that his movies and their sources are basically infantile, glorying in this awareness with a touch of bravado and inviting viewers to wallow in the same fashion. (The relatively somber and allegorical reflections on Japanese notions of gender in Dolls is an uncharacteristic exception.)

His latest, Zatoichi (2003), is a new chapter in one of the longest-running and most successful action franchises in Japanese cinema and as such was virtually destined to be a commercial success. It was in fact a monster hit in Japan and has done quite well in various foreign markets. Miramax, banking on the insulated character of the American audience, has just released it theatrically in the U.S. even though it’s already out on DVD and video in much of the rest of the world. They’ve also seen fit to encumber it with a clumsy new title, The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi.

The character of Zatoichi was originally played by the late Shintaro Katsu in 26 films and over a hundred TV episodes dating back to the early 60s. An itinerant masseur, blind Zatoichi is so acute in his other senses that he can effortlessly slay sighted opponents with the samurai sword he conceals in his cane before they can even make their first move. When he’s not pruning the limbs of his enemies, he’s casually chopping firewood and tossing the logs into an ordered stack, unmasking a female impersonator with his sense of smell, even detecting from sound alone that the dice in a gambling game are loaded. Kitano, who previously lampooned the character on TV, gives Zatoichi a blond mane that suggests he may be Eurasian and subversively hints that he might secretly be able to see after all. He also toys with the superhero’s invincibility: when Zatoichi incurs a shoulder wound late in the picture, the effect is much more shocking than the geysers of blood that routinely spurt from the butchered bodies of his adversaries.

Kitano reserves even sharper barbs for Akira Kurosawa, satirically incorporating elements of both The Seven Samurai (hapless farmers in need of protection) and Yojimbo (the hero who manipulates opposing factions in the same town) into the plot. The pastiches, it seems to me, are not tempered by any spirit of homage: Kitano is brazenly jeering at these cinematic touchstones, hoping to demolish the action tradition they represent in order to replace it with one of his own making.

In the latter part of the film, he exhibits an urge to liberate Zatoichi and himself from the action-movie template completely. It’s as if Kitano’s art-movie sensibility gradually subsumes his genre duties — progressively increasing and highlighting his formalized treatment of sound and movement, which has been figuring in brief and striking montage sequences throughout the picture. There are, for example, percussively edited scenes of farmers and carpenters at work that recall Michael Kidd’s choreography for the 50s musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. This rhythmic stylization returns with a vengeance in the film’s closing scenes, when the action movie suddenly mutates into a tap-dancing musical, with all the characters except Zatoichi himself participating in the hoofing. (As the only one not dancing, the blind swordsman recalls the impresario character in a backstage Hollywood musical from the 30s.) Though the filmmaker has by now ridiculed the martial-arts drama virtually out of existence, the final dance number — actually closer to festive stomping than tapping — somehow manages to transcend irony, conveying instead only Kitano’s childlike exhilaration, with a sense of ease regained.