When I previously reprinted on this site my first Paris Journal for Film Comment, from their Fall 1971 issue, I omitted the entire opening section, largely because of its embarrassing misinformation (both naive and ill-informed) in detailing the background of the ongoing feud at the time between Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif. But for the sake of the historical record, I’ve decided to reprint it now, along with a lengthy letter from Positif’s editorial board and my reply to it two issues later. — J.R.

Of all the gang wars waged over the past thirteen years between Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif, the latest appears to be the most extensive and the least illuminating. When Truffaut ridiculed Positif for anti- intellectualism and self-serving vanity in 1958, Cahiers‘ orientation was Catholic-conservative while its leading rival was surrealist and leftist; the former enshrined Hollywood while the latter denigrated it as imperialist. When Positif launched a lengthy counter-offensive in 1962 (amply documented in Peter Graham’s anthology, The New Wave), the terms of the equation had already begun to shift: many Cahiers critics were already beginning to veer away from their backgrounds as they became filmmakers, and Positif was starting to develop a stable of its own Hollywood auteurs, like John Huston and Jerry Lewis. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1989). — J.R.

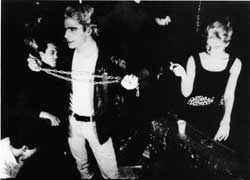

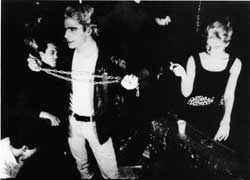

After paying $3,000 for the rights to Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange, Andy Warhol made this very loose adaptation (1965) using direct sound, with such Warhol regulars as Ondine and Edie Sedgwick, Gerard Malanga performing a whip dance, and music by the Velvet Underground. It’s one of Warhol’s very best — and most painterly — films, more interesting for what it does with crowded space than for the S and M. 64 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 8, 1993). — J.R.

A few years ago, world cinema received a shot in the arm from so-called glasnost movies from the former Soviet Union — pictures that had been shelved due to various forms of censorship, mostly political, and were finally seeing the light of day thanks to the relaxation or near dissolution of state pressures. The thought of an American glasnost may seem a little farfetched. But if we start to look at the awesome control exerted by multinational corporations over what we see, particularly in mainstream movies, the definition of what is and isn’t permissible — or, in business terms, what is “viable,” which in this country often comes to the same thing — may seem comparably restricted.

The best movies of 1992 weren’t exactly censored; but given the profound lack of media attention they received they would have achieved much more reality in most people’s minds if they had been. And nothing short of an American-style glasnost would give these films the cultural centrality they deserve. Only three of them received extended theatrical runs in Chicago, and perhaps only one or two got so much as a mention on Entertainment Tonight or in Time, Newsweek, or Entertainment Weekly. Read more