From Nashville Scene (cover story), March 10, 2011. This essay was commissioned by the late Jim Ridley, whose unexpected death was a grievous loss.

I’m sorry that I forgot to mention The Young One, surely one of the most neglected and overlooked of all great Southern films, explored in detail elsewhere on this site. — J.R.

In certain respects, the “Visions of the South” series of Southern

movies being launched in Nashville this week at The Belcourt deserves

to be applauded for its omissions as well as its inclusions. The most

conspicuous of these omissions is probably Robert Altman’s Nashville

(1975), which Brenda Lee once aptly described as “a dialectic collage of

unreality.” (Altman, at least, proved better at handling Mississippi —

in Thieves Like Us the year before Nashville, and in Cookie’s

Fortune a quarter of a century later.)

We all know, of course, that Hollywood and even some of its maverick

celebrities have been guilty of fostering and/or perpetuating false images

of the South from the very beginning. A few other prominent and

dubious examples might include Jean Renoir’s The Southerner

(1945), Martin Ritt’s The Sound and the Fury (1959), Richard

Brooks’ Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), Otto Preminger’s Hurry

Sundown (1967), John Frankenheimer’s I Walk the Line

(1970), and, surely the most bogus of all, Alan Parker’s

Mississippi Burning (1989), with its outlandish errors

involving both Jim Crow and the FBI, just to get started.

But don’t get me started. Part of what’s so satisfying about this film series is that it helps us to forget about outrages of this kind. Speaking as a native of Florence, Ala., I can only feel gratitude for the filmmakers who have gone to the trouble of getting the South right. Admittedly, these judgment calls are highly subjective, and I can’t expect everyone, including every Southerner, to agree with them.

In the case of Robert Mulligan’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) — a film that was ultimately cut from the series — it’s even possible that my misgivings about the Southern details, which made me greatly prefer Harper Lee’s original novel at the time it came out, might conceivably be revised if I revisited both of them today.

For Yankees and other so-called foreigners who imagine that Gone With the Wind — or Mississippi Burning, for that matter — accurately and adequately depict the South, part of the value of this discerning series is to illustrate the maxim that no view of any region that’s as generic and as predigested as theirs are can possibly do justice to it. From this standpoint, personal takes on the South are far better than boilerplate versions, and it’s largely the personal aspects of the movies in this series by such directors as Roger Corman, Robert Duvall, John Ford, David Gordon Green, Monte Hellman, Phil Karlson, Elia Kazan, Charles Laughton, Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Michael Roemer, and Jacques Tourneur that carry the most conviction, at least for me. (Admittedly, Gone With the Wind reflects the personality of David O. Selznick, but this is for the most part only in the same way that the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in its heyday reflected the personality of P.T. Barnum. By which I mean that the stamp of a manufacturer is less personal than the shaping of an artist.)

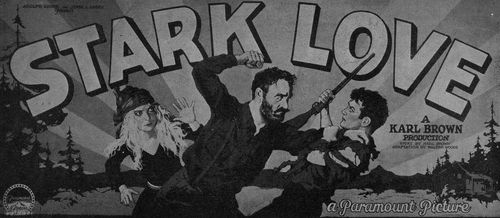

For the record, the programmers couldn’t get every film they wanted; given the scarcity of prints of many older films, this is hardly surprising. Among these, the main absences I’m aware of are two features directed by black filmmaker Spencer Williams, The Blood of Jesus (1941) and Go Down Death (1944); John Huston’s Wise Blood (1979), a particular favorite of mine; and Michael Apted’s Coal Miner’s Daughter (1981). And there are omissions in the series that I regret. One is Stark Love (1927) — a silent picture from Paramount, directed by one of D.W. Griffith’s best cameramen, Karl Brown (a Southerner). Shot on location in the Unicoi Mountains of North Carolina, it was a favorite of James Agee, though all prints appeared to have been lost until film historian Kevin Brownlow discovered one in Prague in 1968. (In fact, the Southern Appalachian International Film Festival in Bristol, Tenn., managed to show this film in October 2009.)

Another is Intruder in the Dust (1949), an adaptation of William

Faulkner’s novel directed by another Southerner, Clarence Brown,

for MGM and filmed on location in Oxford, Miss. Along with Douglas

Sirk’s excellent (but not very Southern and studio-bound) The

Tarnished Angels (1957), an adaptation of Pylon, and Joseph

Anthony’s Tomorrow(1972), derived from a short story of the same

title (and which is included in the Belcourt series), it stands as one

of the three most prestigious Faulkner movie adaptations. Perhaps

it’s significant that they’re all derived from relatively minor works.

Still, the bounty of what the programmers have managed to

snare is substantial. It seems appropriate that the director best

represented here, Elia Kazan, who has no less than three

features in the series — Wild River(1960) at the beginning,

and Baby Doll(1956) and A Face in the Crowd(1957) a

week later — is one of the most attentive when it comes to

regional accents. Kazan hired a “speech consultant,”

Margaret Lamkin, for this purpose for his stage production

of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and he

employed her again for Baby Doll, which Williams also

wrote. His handling of both rural Arkansas and nearby

Memphis in A Face in the Crowd and the Tennessee

Valley in Wild River (one of his least known movies,

but arguably his very best) seems equally attentive.

(Based on a conversation I had recently with the

Missouri Ozarks vocalist Marideth Sisco, who worked

on the Oscar-nominated Winter’s Bone, it seems that

Debra Granik, the director/co-writer of that wonderful

feature, was comparably exacting about the regional

accents in her own film. I can’t vouch for the treatment

of Arkansas in Raymond St. Jacques’ 1973 “blaxploitation”

flick Book of Numbers, a film I haven’t seen that’s

showing in the Belcourt series, but it sure sounds intriguing.)

A Face in the Crowd was scripted and based on a story by

Budd Schulberg, who had also recently written On the

Waterfront for Kazan — and wasn’t quite as attentive to

Southern types as Kazan was. (Kazan’s very first film, an

18-minute documentary short made in 1937, was called The

People of the Cumberland.) But it’s no surprise that the

Memphis of A Face in the Crowd is more plausible as well

as less mythological than the one in Jim Jarmusch’s

Mystery Train — a Tennessee fantasy that might be said to

contain several virtues in spite of its lack of local verisimilitude.

There are many other favorites of mine in the series, and it seems significant that over half of the films selected are period movies. This is even true technically of Phil Karlson’s exceptionally seedy docudrama The Phenix City Story (1955), filmed on location and set in the very recent past. For my money, this is probably the best commercial movie ever set in Alabama; its only possible competitor would be Nothing But a Man (see below), which comes just before the series’ end. And the silent 1925 classic of black pioneer Oscar Micheaux, Body and Soul, starring the great Paul Robeson, will be shown closing night with a commissioned score (by Roy “Futureman” Wooten and arranger Gil Fray, performed live by Futureman & the Black Mozart Ensemble).  Jacques Tourneur’s Stars in My Crown(1950) isn’t exactly generically Southern, despite a local Klan that figures pivotally in the plot, and in some ways its setting seems closer to a town one would find in a Western. (In fact, at least one French critic has classified this film as a Western.) Tourneur, best known today for his film noir Out of the Past and some horror pictures (Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie, The Leopard Man, and Curse of the Demon), has been a relatively late discovery of mine, but I’ve come to regard him as a major and underrated figure. Stars in My Crown was his favorite among his own features, and it’s my favorite as well — a beautiful and nuanced piece of period Americana that performs the difficult task of depicting good people convincingly, and without any trace of sentimentality.

Jacques Tourneur’s Stars in My Crown(1950) isn’t exactly generically Southern, despite a local Klan that figures pivotally in the plot, and in some ways its setting seems closer to a town one would find in a Western. (In fact, at least one French critic has classified this film as a Western.) Tourneur, best known today for his film noir Out of the Past and some horror pictures (Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie, The Leopard Man, and Curse of the Demon), has been a relatively late discovery of mine, but I’ve come to regard him as a major and underrated figure. Stars in My Crown was his favorite among his own features, and it’s my favorite as well — a beautiful and nuanced piece of period Americana that performs the difficult task of depicting good people convincingly, and without any trace of sentimentality.  The same could be said for Lillian Gish’s matriarchal character in Charles Laughton’s only feature as a director, The Night of the Hunter(1955), set during the Depression. Here is another film that I don’t normally regard as Southern, but this is undoubtedly because my Deep South background tends, quite unfairly, to minimize or overlook the Southern aspects of such “fringe” states as West Virginia, where Davis Grubb, the author of the novel, came from. And one might similarly and pedantically question the Southern credentials of Roger Corman’s The Intruder(1961) by virtue of the fact that it was shot in Missouri, even though this didn’t by any means free Corman and his co-workers from having to contend with local prejudice while they were shooting it. This quickie is a fairly faithful — and, as I recall, fairly suspenseful — low-budget adaptation of Charles Beaumont’s contemporary novel about a rabble-rousing bigot (William Shatner) who enters a small Southern town to stir up trouble shortly before its local high school becomes integrated.

The same could be said for Lillian Gish’s matriarchal character in Charles Laughton’s only feature as a director, The Night of the Hunter(1955), set during the Depression. Here is another film that I don’t normally regard as Southern, but this is undoubtedly because my Deep South background tends, quite unfairly, to minimize or overlook the Southern aspects of such “fringe” states as West Virginia, where Davis Grubb, the author of the novel, came from. And one might similarly and pedantically question the Southern credentials of Roger Corman’s The Intruder(1961) by virtue of the fact that it was shot in Missouri, even though this didn’t by any means free Corman and his co-workers from having to contend with local prejudice while they were shooting it. This quickie is a fairly faithful — and, as I recall, fairly suspenseful — low-budget adaptation of Charles Beaumont’s contemporary novel about a rabble-rousing bigot (William Shatner) who enters a small Southern town to stir up trouble shortly before its local high school becomes integrated.  At the opposite extreme from The Intruder are two period idylls about small-town America. John Ford’s Steamboat ‘Round the Bend (1935) and The Sun Shines Bright(1953) are arguably, along with the earlier Judge Priest (a sort of prequel to The Sun Shines Bright), the best films he ever made about the postwar Old South. Steamboat ‘Round the Bend unfolds on the Mississippi River in the late 19th century, while The Sun Shines Bright is set in a small town in Kentucky in the early 20th. Yet both films, like so many other major works of Ford, reek of memories and reverberations from the Civil War.

At the opposite extreme from The Intruder are two period idylls about small-town America. John Ford’s Steamboat ‘Round the Bend (1935) and The Sun Shines Bright(1953) are arguably, along with the earlier Judge Priest (a sort of prequel to The Sun Shines Bright), the best films he ever made about the postwar Old South. Steamboat ‘Round the Bend unfolds on the Mississippi River in the late 19th century, while The Sun Shines Bright is set in a small town in Kentucky in the early 20th. Yet both films, like so many other major works of Ford, reek of memories and reverberations from the Civil War.  Anthony Mann’s 1958 adaptation of Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre — like Ford’s earlier (1941) and less satisfying version of Tobacco Road, Caldwell’s other famous novel dating from the Depression — is full of conflicted sentiments about its Georgia cracker characters, seeing them alternately as sympathetic victims and as hopelessly retarded hillbillies. But Robert Ryan’s standout performance as the crazed Ty Ty helps to encompass the seeming contradictions. The no less lurid Baby Doll, shot in rural Mississippi two years earlier, outraged many of the Southerners who saw it. The movie was widely banned in the South in 1956 — ostensibly for its handling of sex (which seems rather odd today, given the reticence and ambiguity about sex in the plot), but perhaps more indirectly because of the unflattering portrait it gave of Southern yokels.

Anthony Mann’s 1958 adaptation of Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre — like Ford’s earlier (1941) and less satisfying version of Tobacco Road, Caldwell’s other famous novel dating from the Depression — is full of conflicted sentiments about its Georgia cracker characters, seeing them alternately as sympathetic victims and as hopelessly retarded hillbillies. But Robert Ryan’s standout performance as the crazed Ty Ty helps to encompass the seeming contradictions. The no less lurid Baby Doll, shot in rural Mississippi two years earlier, outraged many of the Southerners who saw it. The movie was widely banned in the South in 1956 — ostensibly for its handling of sex (which seems rather odd today, given the reticence and ambiguity about sex in the plot), but perhaps more indirectly because of the unflattering portrait it gave of Southern yokels.

Far more ambiguous is The Apostle(1997), a neglected gem that was written as well as directed by its star, Robert Duvall. Refusing to buy into the Elmer Gantry stereotype, which suggests that every fundamentalist preacher who shows signs of being a scoundrel is also a hypocrite, Duvall throws us into a subculture of devout belief without the sort of moral signposts that many city slickers have grown to depend on defensively and as a matter of automatic reflex. Sonny, Duvall’s troubled and troubling preacher, may be a warped creature who lies to himself, but on the basis of everything we see and hear, he believes deeply in saving souls. And by making all the church services interracial, Duvall complicates our responses still further, especially if one stereotypes most white fundamentalists as racists, as many glib Yankees are prone to do.

Far more ambiguous is The Apostle(1997), a neglected gem that was written as well as directed by its star, Robert Duvall. Refusing to buy into the Elmer Gantry stereotype, which suggests that every fundamentalist preacher who shows signs of being a scoundrel is also a hypocrite, Duvall throws us into a subculture of devout belief without the sort of moral signposts that many city slickers have grown to depend on defensively and as a matter of automatic reflex. Sonny, Duvall’s troubled and troubling preacher, may be a warped creature who lies to himself, but on the basis of everything we see and hear, he believes deeply in saving souls. And by making all the church services interracial, Duvall complicates our responses still further, especially if one stereotypes most white fundamentalists as racists, as many glib Yankees are prone to do.

Ray’s penultimate Hollywood assignment, Wind Across the Everglades(1958) is a kind of litmus test for auteurists. This philosophical adventure story, set in turn-of- the-century Florida, was director Nicholas Ray’s penultimate Hollywood assignment, though he was fired before the end of shooting and barred from the final editing by screenwriter Budd Schulberg, who produced the film with his brother Stuart. (In his introduction to the published screenplay, Schulberg barely mentions Ray at all.) An ecological parable, it pits an earnest schoolteacher-turned-game warden (Christopher Plummer) against a savage poacher of wild birds (Burl Ives) heading a grungy gang in the swamps. Ray’s masterful use of color and mystical sense of equality between the antagonists (also evident in Rebel Without a Cause and Bitter Victory) are made all the more piquant here by his feeling for folklore and outlaw ethics as well as his cadenced mise en scène. The result is somewhat choppy — one gets a sense of subplots being truncated — yet the film builds to a powerful encounter between Plummer and Ives, and Ray’s personal touches are unmistakable. (There’s even an upside-down point-of-view shot that’s similar to the ones in Ray’s Rebel and Hot Blood.) The performances are quite striking, especially Chana Eden’s as the female lead — not to mention cameos by Gypsy Rose Lee, author MacKinlay Kantor and Peter Falk (in his film debut).

Inevitably, there are a few films in the Southern series that I

don’t much care for — Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1965),

Reflections in a Golden Eye(1967), Deliverance(1972) and

Stay Hungry (1976) — but I can remember only the second of

these well enough to offer any comments. John Huston’s

adaptation of Carson McCullers’ tortured novel, Reflections

in a Golden Eye concerns an army major at a peacetime

camp in Georgia who’s a repressed homosexual (Marlon

Brando), his adulterous wife (Elizabeth Taylor) and various

other unhappy characters and gothic traumas. Originally shot

(by Aldo Tonti) in gold-tinted hues that suggested caterpillar

guts — a gimmicky effect that was widely applauded at the

time for artistic originality, though its aesthetic function

was dubious — the film now circulates in more conventional

color. Either you like this movie a lot or you run screaming

for the exit; I personally find it fairly rough going.

With the possible exception of Iguana (1988), which is almost

completely unknown, Cockfighter (1974) is probably the most

underrated and unjustly neglected work by Monte Hellman

(Two-Lane Blacktop). Shot by the great cinematographer

Nestor Almendros on location in Georgia (partly — and

climactically — in Flannery O’Connor’s hometown,

Milledgeville, which seems entirely appropriate), it wryly

follows the absurdist progress of a man who trains fighting

cocks (Warren Oates in one of his best performances) and

who takes a vow of silence after his hubris nearly puts him

out of the game, though he continues to narrate the story off

screen. Produced by Roger Corman as an exploitation item

for the drive-ins, this performed so badly in that capacity

that it was recut and retitled more than once (as Wild

Drifter, Gamblin’ Man, and Born to Kill, the title it

appears under in the Belcourt series). But as a dark comedy

and a closet art movie, it delivers and lingers. Among the

supporting players here are Richard B. Shull, Harry Dean

Stanton, Millie Perkins, Troy Donahue, and screenwriter

Charles Willeford, the author of the source novel.

The series nearly concludes with two features set in Alabama —

Bob Rafelson’s 1976 Stay Hungry, co-starring Jeff Bridges, Sally

Field, and in his first major role (if one discounts the 1969

Hercules in New York), Arnold Schwarzenegger; and Nothing

But a Man(1964). The latter was directed by the able Michael

Roemer (who made the even more neglected The Plot Against

Harry five years later) from a script written in collaboration with

Robert M. Young, who served as cinematographer and went on to

his own directorial career. It’s a sincere, intelligent and effectively

acted independent feature — actually shot in New Jersey, although

it doesn’t look it — about a black worker (Ivan Dixon) and his

wife (Abbey Lincoln) struggling against prejudice and trying to

make a life for themselves in Alabama, further distinguished by

a supporting cast that includes Gloria Foster, Julius Harris,

Martin Priest and Yaphet Kotto.

In George Washington(2000), to be shown before the two Alabama films, the writer-director David Gordon Green sometimes comes across as a gifted poet who hasn’t yet mastered prose. His characters and images are memorable, but his story about working-class kids, most of them black, in a small town in North Carolina is elusive and occasionally puzzling. Working with nonprofessional actors who improvise some of their dialogue, Green seems at certain junctures to be brandishing strangeness like a crown. But the lyricism of his ‘Scope framings, junkyard settings and extremely vulnerable teenage characters registers loud and clear even when some of his ideas come across as amorphous or self-conscious.

In George Washington(2000), to be shown before the two Alabama films, the writer-director David Gordon Green sometimes comes across as a gifted poet who hasn’t yet mastered prose. His characters and images are memorable, but his story about working-class kids, most of them black, in a small town in North Carolina is elusive and occasionally puzzling. Working with nonprofessional actors who improvise some of their dialogue, Green seems at certain junctures to be brandishing strangeness like a crown. But the lyricism of his ‘Scope framings, junkyard settings and extremely vulnerable teenage characters registers loud and clear even when some of his ideas come across as amorphous or self-conscious.

Though George Washington isn’t especially violent, particularly by

contemporary standards, it arguably has more to say about the

desperation behind the Columbine High School killings than any

number of editorials. You have to bring a lot of yourself to this film if

you want it to give something back, but the rewards are considerable.

And indeed, I think the same could be said for this film series as a whole.