From the January 26, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Films by Robert Bresson

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Two types of film: those that employ the resources of the theater (actors, directors, etc.) and use the camera in order to reproduce; those that employ the resources of cinematography and use the camera to create….Cinematography: a new way of writing, therefore of feeling. — Robert Bresson, Notes on Cinematography

Among the people of my acquaintance who know a lot about film, most — perhaps all — consider Robert Bresson the greatest living filmmaker. Because he’s in his early 90s, the possibility of his making another movie — his last was L’argent (“Money”) in 1983 — is remote. (Most biographical sources place his birthdate in 1907, but reliable informants have told me that this very private individual shaved at least a couple of years off his age some time ago, apparently to extend his credibility as a working director with insurance companies.)

In spite of its importance, his work may have difficulty surviving, because most of it doesn’t “translate” to video. The reasons are complex, but for starters I would suggest that two central factors involved are sound presence and the framed image. It might be argued that both obstacles can be overcome with a good home projection system and a good set of speakers, but few viewers have this sort of equipment at their disposal. And even if they do, practically none of Bresson’s work is available on laser disc, and only a handful of his major films are on video at all. It’s my experience that L’argent — a shocking and devastating work like few others — all but ceases to exist on video; and though A Man Escaped (1956) and Pickpocket (1959) fare somewhat better, this may be true only if you’ve already seen them in theaters. I should also mention that I saw A Man Escaped on a big screen at the Toronto film festival last September, and it had a bigger impact on me than all the Bresson movies I’ve ever seen on video combined.

So it’s an event of some importance that Facets Multimedia is devoting the next two weeks to showing 8 of Bresson’s 14 films, all but two of them (Diary of a Country Priest and L’argent) in 35-millimeter prints. Seven films will be screened this week, to be followed by a week’s run of The Devil, Probably (1977), Bresson’s penultimate feature — a film that only recently acquired an American distributor. Three of his greatest films — Les dames du Bois de Boulogne, 1945; Au hasard Balthazar, 1966 (for me Bresson’s supreme masterpiece); and Mouchette, 1967 — and three relatively minor ones are missing from the retrospective, but it still offers a rare opportunity to come to grips with a master of awesome power. For people not yet acquainted with this giant, an extended look at his work will transform their understanding of what the art of film can be and do — and incidentally explain why seeing that work on video could never be a substitute.

It’s worth noting that the current dominance of the star system and the practice of home viewing are intertwined. If a fundamental formal element in film art is the framed image, the absence of a clearly demarcated frame in most videos, which eliminate the margins of the film frame, virtually rules out certain kinds of visual content. Stars tend to survive this cropping because usually they need only to be recognized to register and because they’re traditionally placed in the center of frames. But if shots are designed as complex expressive units to be juxtaposed with shots that precede and follow them (an art Bresson calls “cinematography”), paring away portions of those shots interferes with that design. (Bresson started out as a painter, and many of his notions about his art seem derived from painting.) Add to this the fact that Bresson’s complex designs depend on a refusal to use professional actors, much less stars — a decision that affects everything else about his work — and you begin to understand why his art is so removed from the options of commercial movies and video.

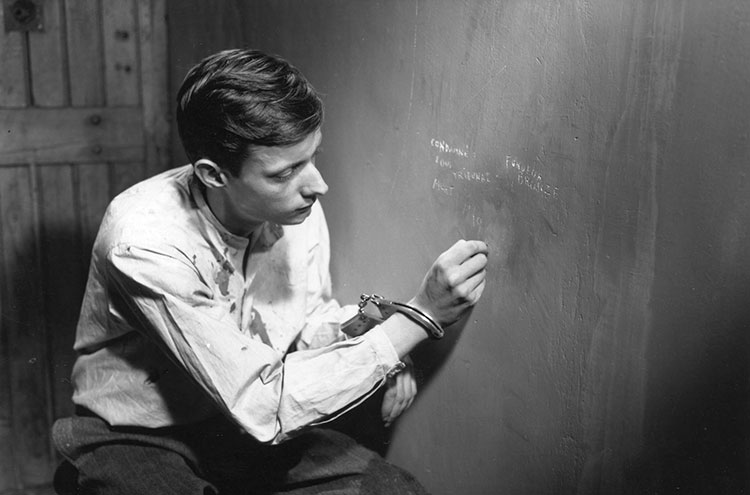

In place of professional actors Bresson uses what he calls “models,” people with no acting experience who are rigorously trained by him to express as little as possible in their movements, expressions, and line readings. The reasons for this are quite simple, though so much at loggerheads with usual moviemaking practice that they require some getting used to and initially may appear perverse. For Bresson, the willed expressiveness of actors, appropriate and necessary to theater, competes with the expressiveness of sounds and images that are under the control of a filmmaker. They also compete with the expressiveness of what people are as opposed to how they wish to represent themselves — their material and spiritual essence as human beings as opposed to their cover stories. The choice of models is of paramount importance to Bresson — and many of his models, as luminous and as memorable as most stars one could name, have gone on to become actors and even stars with other directors (most notably Dominique Sanda in the 1969 Une femme douce) — but the beauty and power of these individuals are qualities that emerge from the films themselves; they are never a matter of willed “performances.” As Bresson expresses it in his Notes on Cinematography, a slim volume of reflections that resemble Chinese fortune-cookie messages in their brevity, “BEING (models) rather than SEEMING (actors).“

This doesn’t mean that Bresson downplays his models or “plays up” his sounds and images. On the contrary, his approach to the brute reality of sounds and images is every bit as elemental as his approach to people; like his practice of filming in natural locations rather than studio spaces, it points to an old-fashioned sense of craft and a fundamental trust in — and reliance on — material reality. The second aphorism in his Notes on Cinematography reads, “The faculty of using my resources well diminishes when their number grows.” In other words, the fewer elements he uses, the more he can do with them. By the same token, the less his sounds, images, and models express individually, the more he can control them — and the more he can control them, the more they can express, especially in tandem. (“The flatter an image is,” he writes, “the less it expresses, the more easily it is transformed in contact with other images.”)

More an essentialist than a minimalist, Bresson can nevertheless produce a maximal emotional effect with a minimum of means. From The Trial of Joan of Arc on, all of his features, with the arguable exception of Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), are essentially tragedies, brimming with despair and often shattering in their effect; many of his late films — most notably Mouchette, Une femme douce, and The Devil, Probably — are preoccupied with suicide (French teenagers were once barred from seeing The Devil, Probably, which was held to be “an incitement to suicide”). Yet he achieves this through pared-down methods such as focusing on a person’s feet or hands for long stretches. The mystery of human personality — and in Au hasard Balthazar of a donkey — lies at the heart of his work, but his means of arriving at that mystery is always concrete and precise.

Another of his central principles of economy is to replace an image with a sound whenever possible. (Two of his reasons, cited in a 1966 interview with Jean-Luc Godard: “the ear is much more creative than the eye” and “you must leave the spectator free.”) In A Man Escaped — a meticulous account of a prison escape by a French resistance fighter in Lyons, based on an autobiographical account by Andre Devigny — this principle extends to the hero’s offscreen narration, which alludes to narrative developments that occur over weeks and months (in contrast to the present-tense quality of all the seen material), as well as the remarkable use of offscreen sounds to convey Devigny’s sense of the world outside his cell, sounds that become part of his relentless, obsessive will toward freedom.

The greatest of all prison-escape movies and the greatest Bresson film for me after Au hasard Balthazar (as well as the biggest popular success in Bresson’s career), A Man Escaped is the first film being screened in Facets’ retrospective, and to my mind it represents an ideal introduction to his work. Much the same case could be made for Pickpocket, which is screening the same night — an existential tale about crime, urban solitude, and redemption with uncredited lifts from Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Some of these lifts are banal, and the hero’s sudden redemption at the film’s end is unbelievable (curiously these aspects of the film have become cornerstones in the scripts and films of Paul Schrader, from Taxi Driver to American Gigolo to Light Sleeper). But the poetry found in the urban solitude of the hero and his self-education as a pickpocket remains ethereal and oddly uplifting, and one sequence in which he consorts with other pickpockets in the Gare de Lyon has the exhilaration of a breathtaking ballet.

As luck would have it, these two films were the first Bresson features I ever saw, back in the early 60s, and I’ve been a passionate Bressonian ever since. But I couldn’t claim that everyone who sees them feels the same way — or even that everyone who likes them does so for the same reasons. In her ardent defense of Bresson in Against Interpretation Susan Sontag argues that “ideally, there is no suspense in a Bresson film,” pointing out that the very title A Man Escaped does away with suspense by telling us that the hero succeeds. This sounds fine in theory, but in my experience A Man Escaped is just about as suspenseful as a prison-escape movie gets, and the suspense hardly ever stops in Pickpocket either.

Maybe it depends on one’s involvement in the stories and characters. For me, Bresson’s 1950 Diary of a Country Priest and 1962 The Trial of Joan of Arc — two of his most austere works — generate hardly any suspense at all, but that’s probably because they’ve never fully engaged me, which may or may not be attributable to my not having seen either film in a decent print. But to someone more plugged into these films’ subjects, they may seem positively Hitchcockian.

When A Man Escaped was screened in Toronto last fall as a personal selection of director Agnieszka Holland, who introduced the film and led a discussion afterward, the first postscreening remark was from a lady in the front row, who basically said, “This is certainly an artistic film, but it seems to me that the narration is completely unnecessary — it doesn’t tell you anything you don’t already know. What do you think?” Holland smiled, shrugged, and said, “I don’t know. You might be right” — a response that shocked me so much I still haven’t recovered. (Could this be the result of Holland’s own desperate attempts to swim in the commercial waters of Eurobabble productions like the significantly titled Total Eclipse?) But the woman’s objection does point to a dialectical use of offscreen narration in Diary of a Country Priest, A Man Escaped, Pickpocket, and Une femme douce that’s so contrary to commercial norms — at times entailing an anticipation, an echo, a modification, or even an outright contradiction of the visual information being offered — that one may have to get past one’s knee-jerk, Hollywood-trained responses to appreciate all the expressive and formal functions it has for Bresson. (As Manny Farber noted of Une femme douce, “The movie is a brain-twister in which few sentences connect to the image they accompany. A young bride jumps up and down on her new bed, and her husband, the ultimate in prissiness and mundaneness, says, ‘I threw cold water on her ecstasy.'”)

But the main disagreement I have with a good many other Bresson fans is the matter of how one deals with the films’ religious and spiritual aspects. Despite Bresson’s alleged and at times avowed Jansenism — a heretical strain in Gallican Catholicism that believes in predestination — it seems to me that his best films have more to do with materialism than with the “transcendental” qualities most critics have written about.

Asked in a 1962 interview whether he believed “in a spiritual domain,” Jacques Rivette replied, “Maybe, but only through the concrete. If that means being materialist, I think that’s what I am more and more.” The same attitude and development clearly inform Bresson’s career, to such a degree that his last three films — Lancelot du lac (1974), The Devil, Probably, and L’argent — could be described as atheist. There’s also a powerful and wholly material eroticism in his work that makes a quantum leap around the time of Pickpocket and continues, more or less unabated, through L’argent — an eroticism so dependent on elements of sound and image that in Lancelot, for example, the constant rattle of armor plays a central role in defining and even creating our sense of the softness and vulnerability of flesh, Guinevere’s as well as Lancelot’s. (First conceived in the early 50s, Lancelot registers in its opening and closing sequences as a horrified testimony to the savagery of war, and in its handling of this theme comes across as resolutely modern — in striking contrast to Une femme douce, an update of a Dostoyevsky story, whose title heroine comes across as strangely medieval, like a maiden in a castle waiting to be rescued.)

Bresson’s last five features are his only films in color, and as a friend of mine recently observed, his use of color led to a radical reformulation of his films: you’re not always sure what to look at in the shots, which never happens in his black-and-white films. This is less true of Lancelot du lac, where the color functions mainly as black and white does (apart from serving as a cue, in the color of banners or tights, that lets us recognize characters in armor). But in the other four features a dreamy, mannerist slickness enters Bresson’s world for the first time, with consequences that aren’t always beneficial, though there’s a lyrical abstraction in some of the images that’s highly evocative. (I haven’t seen Une femme douce in about a quarter of a century, but I’ve never forgotten the flurry of elliptical shots depicting the heroine’s suicidal leap from a balcony — a montage that’s briefly recalled during the suicide that occurs near the beginning of Bill Forsyth’s wonderful Housekeeping, playing this Thursday at Doc Films.)

These are the films in which Bresson appears to be commenting most directly on what he finds hateful about the contemporary world. (The same emotions are clearly present in Au hasard Balthazar and Mouchette, but the rural setting of both pictures makes their social critiques seem more attenuated.)

One is better off seeing The Devil, Probably — a potent but difficult tale of adolescent suicide in which mannerisms associated with poker-faced nonacting and French fashion periodically threaten to overwhelm the deeply felt sense of tragedy — only after seeing some of Bresson’s black-and-white work or Lancelot du lac. As a first taste of his work, it may simply prove too weird, though in 1977 a whole generation of French cinephiles responded directly and viscerally to it, and it exerted a lasting influence on them.

The only Bresson feature apart from Au hasard Balthazar based on an original story, The Devil, Probably more or less begins with five disaffected youths going off to a political rally where a leader appears before a microphone to say, “I’m calling for destruction….Destruction is for everyone.” The crowd cheers wildly after each phrase. Soon afterward one sees other students watching newsreel footage about ecological disasters across the globe, culminating in the clubbing of baby seals. Then some of the youths go off to a church, where an angry discussion about the modern world and religion is brutally interrupted by the sounds of a vacuum cleaner and an organ being tuned. The rage expressed here, combined with the spooky precision of the pared-down, almost neutralized style, turns many of the lines into non sequiturs — there’s a sense of mortification combined with sensationalism that suggests the improbable fusion of Bresson with a headline monger like Samuel Fuller. (The rage is still present in L’argent, Bresson’s most compressed indictment of the modern world — a contemporary adaptation of a story by Tolstoy — but it’s fully mastered and consummately measured.)

Bresson has steadfastly kept his personal life hidden from the public, and I can think of few reasons for trying to invade that privacy. But as I suggested a couple of months ago while writing about Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, it seems entirely possible that Bresson’s hallmarks as a filmmaker — including his use of offscreen sounds to replace images and the sense in all his films of souls in hiding, of buried identities and emotions — might be traceable in part to the nine months (1940 and ’41) he spent as a POW in a German concentration camp and his subsequent experience of the German occupation of France. I’m thinking not only of A Man Escaped but also of Les dames du Bois de Boulogne, made during the occupation. Speaking last year to film historian Bernard Eisenschitz, Godard provocatively called Les dames — a contemporary melodrama adapted from an incident in Denis Diderot’s 18th-century novel Jacques the Fatalist — the “only” film of the French resistance. Such an interpretation can be debated, but it seems to me far more fruitful to see Bresson’s style growing out of a concrete historical experience than to treat it as a timeless, transcendent expression of abstract spirituality.

For a couple of nights in 1970 I was an extra on Four Nights of a Dreamer (another film missing from the Facets tribute, but on the whole a minor one) and had the opportunity to watch Bresson direct. The most striking characteristic about him in relation to other directors I’ve seen working was his isolation: most of his instructions were relayed through his assistant, a Belgian woman, with the result that most of the extras thought she was the director. A surprising number of people on the crew seemed to have little or no sense of who Bresson was, apart from the fact that he was old and “difficult”; he walked off once in a huff after midnight, while everyone stood around shivering in the October cold waiting for him to come back.

This prickly side can be traced back to his very first effort as a director — a sarcastic, surrealist slapstick short with songs called Les affaires publiques (1934), set in a mythical country, with shades of Jean Vigo and Million Dollar Legs. A curiosity that was lost for years until the Paris Cinematheque discovered a slightly shortened print a few years ago, it has the same raw physicality as his increasingly bleak features and the same spirited anger about pomp and hypocrisy, greed and artifice, that informs his work all the way through L’argent. Facets’ Charles Coleman, who was unaware this film had been rediscovered when he put together this retrospective, hopes to show it on a future occasion in its still-unsubtitled state.

If film — not to be confused with star vehicles or videos — is currently in the process of disappearing, it seems more than likely that the work of Robert Bresson will disappear as well. If you want to get some idea of what the world might lose you should hurry off to Facets Multimedia and take a good, hard look at some of the last traces of an art that, appropriately enough, is as apocalyptic as any modern work I can think of. Chances are, 20 years from now you’ll be grateful for having had a chance to pay your final respects.