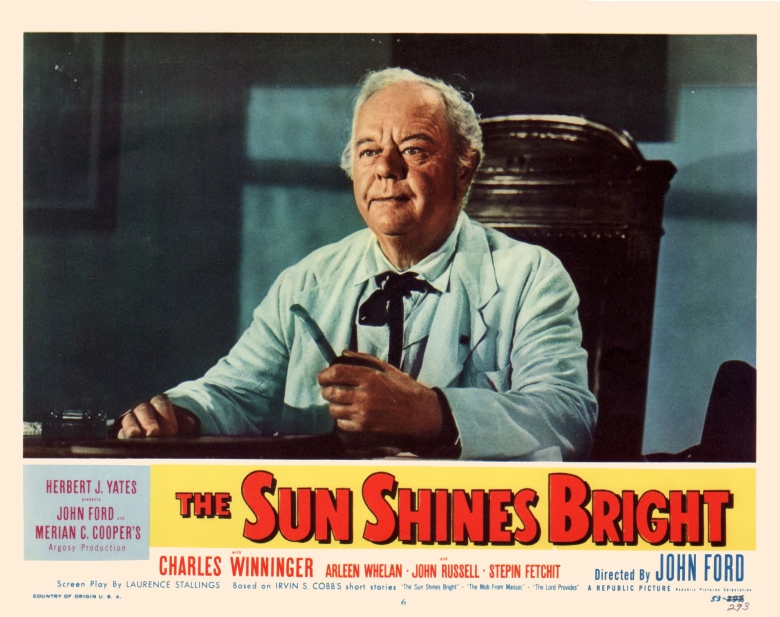

This was originally published by the Viennale in 2004 as part of a catalogue (Die Früchte des Zorns und der Zärtlichkeit) accompanying a program of John Ford films selected by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet; it subsequently appeared online in Rouge no. 7 (2005). One can also access Kevin Lee’s two-part video featuring my commentary on both The Sun Shines Bright and Gertrud here and here. — J.R.

“The Doddering Relics of a Lost Cause”: John Ford’s The Sun Shines Bright

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

My father helped to run a small chain of movie theaters in northwestern Alabama that were owned by my grandfather while I was growing up. He and my mother weren’t cinephiles, but on two separate occasions they took the trouble to travel to cities in different states to attend world premieres in the South while I was growing up. One was for a big Southern film from a big studio (M-G-M), Gone with the Wind, held in 1939 in Atlanta. The other was for a small Southern film from a small studio (Republic Pictures), The Sun Shines Bright, held in 1953 in what I believe was a city in Tennessee — most likely Nashville or Chattanooga, possibly Memphis or Knoxville. The film is set in a town called Fairfield, Kentucky, so one may well ask why its premiere was held in Tennessee. I don’t know the answer to this question, but expect it had something to do with some form of expedience on the part of Republic Pictures.

I was ten years old when my parents saw the latter film, and although I was keeping a diary for much of that year that contained many references to movies, I never wrote down anything in this diary about The Sun Shines Bright — not even when it showed at one of my family’s theaters a few weeks or months after the premiere. I can vividly remember seeing it, however, and, just after I did, asking my father about the famous people he met at a dinner he attended at the movie’s premiere and what each one of them was like. At the age of ten, I already knew who John Ford was — along with Alfred Hitchcock, Cecil B. De Mille, and Walt Disney, he was one of the only auteurs I knew about, and I had already seen a few of his westerns by then, such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon — and to this day I can remember being told that Ford wasn’t at the premiere but that several of the leading actors were: at the very least Charles Winninger (Judge William Pittman Priest) and John Russell (Ashby Corwin), since I clearly remember my father speaking about these two; most likely Stepin Fetchit (Jeff Poindexter) and Arleen Wheeler (Lucy Lee Lake); and probably some others as well. I should add that by the age of ten, I was already well aware of the difference in market power between Gone with the Wind and The Sun Shines Bright, but I still didn’t realize that the stars of the latter film weren’t famous.

Today The Sun Shines Bright is my favorite Ford film, and I suspect that part of what makes me love it as much as I do is that it’s the opposite of Gone with the Wind in almost every way, especially in relation to the power associated with stars and money. Although I’m also extremely fond of Judge Priest, a 1934 Ford film derived from some of the same Irvin S. Cobb stories, the fact that it has a big-time Hollywood star of the period, Will Rogers, is probably the greatest single difference, and even though I love both Rogers and his performance in Judge Priest, I love The Sun Shines Bright even more because of the greater intimacy and modesty of its own scale. Apparently Ford did as well, because, along with Wagonmaster — which it resembles in its low budget, its lack of stars, and its focus on community — I believe this is the film of his that he cited most often as a personal favorite.

Let me attempt to sketch a synopsis of the film —- which is no easy matter, because it’s cluttered with events and characters in spite of the fact that it’s quite leisurely in its pacing. Around the turn of the century, soon after Ashby Corwin returns by riverboat to his home town in Kentucky and starts courting Lucy Lee Lake, Judge Priest, an alcoholic judge who’s up for re-election, cared for by his black servant Jeff Poindexter, goes to court and defends U.S. Grant Woodford (Elzie Emanuel), a teenage black banjo player, and Mallie Cramp, the town madam, against the charges of his stuffy opponent Horace K. Maydew. That night, he attends a regular meeting of Confederate veterans, borrowing an American flag for the occasion from the Union veterans, and announces that he’ll take home the Confederates’ portrait of General Fairfield and his late wife. (For the past 18 years, Fairfield, whose banished daughter —- Lucy Lee’s mother — became a prostitute, has refused to attend the Confederate meetings, and Priest is afraid that Lucy Lee will discover that she’s his granddaughter if she sees the painting and notices that she looks exactly like his late wife.)

Meanwhile, Lucy Lee’s prostitute mother (Dorothy Jordan) arrives in town, heading for Mallie Cramp’s bordello, and collapses. She’s taken to the home of Dr. Lake (Russell Simpson) for treatment, where she glimpses Lucy Lee, his niece, just before she dies. Rushing over to Priest’s house, Lucy Lee sees the family portrait and discovers her true identity. Meanwhile, a local girl has been raped and U.S. Grant Woodford, tracked down by bloodhounds, has been arrested as the rapist.

The next day, Priest stands outside the prisoner’s cell and with a gun prevents a lynching from taking place. (1) That night, Mallie coveys to Priest the dying wish of Lucy Lee’s mother that she receive a proper local funeral. Ashby takes Lucy Lee to a local dance, where disapproving looks compel her to leave around the same time that Buck, a romantic rival of Ashby who led the lynch mob, is identified as the true rapist, and shot while trying to escape with a captive Lucy Lee.

On the following day, Election Day is interrupted by the appearance of a white hearse, a carriage full of prostitutes, and Priest, gradually joined by about a hundred more local people, who all wind up at a black church for the funeral. There Lucy Lee is joined by General Fairfield and Priest delivers a sermon.

The men who wanted to lynch U.S. Grant turn up to vote for Priest, making the election an even tie that Priest breaks by voting for himself. That evening, practically the whole town parades past Priest’s house, paying him tribute — first the white people, and then many of the black people, who serenade him, along with Jeff, as he retreats into his empty house.

At the age of ten, I had some trouble following certain parts of the movie’s plot. Some of this was because of the Production Code, which made Mallie Cramp’s status as a prostitute completely unclear to me, and some was because of the movie’s sheer fancifulness. The early scene in the courtroom combines those two problems by having Mallie Cramp brought to court for unexplained reasons and U.S. Grant Woodford charged by Maydew for refusing to support his uncle —- a charge that we immediately learn is baseless and which also seems to be a highly improbable reason for Maydew going to court, even in postbellum Kentucky. (As we quickly discover, it’s really nothing more than an excuse for Judge Priest and the movie’s audience to hear the boy’s banjo-playing — providing yet another echo of Judge Priest, which had many more courtroom scenes, as well as the comic idea of American courtroom justice making room for a certain kind of musical entertainment with specific political and historical overtones, e.g., “Marching through Georgia” and “Dixie”.)

Still another reason why I had some trouble following the plot was some fairly arbitrary and apparently vindictive cuts to the film made or at least ordered by Herbert J. Yates, the head of Republic Pictures, totaling about ten minutes. According to Joseph McBride in Searching for John Ford (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), “The full hundred-minute version, which played theatrically overseas, was rediscovered when Republic inadvertently used it as a master for the 1990 videotape release.” Lamentably, this full version doesn’t appear to be available on film today, but the video does make the plot much easier to follow.

***

The Sun Shines Bright had a particular significance in the Deep South because of its Southern details. But so did other films by other important directors during this era, sometimes for less direct reasons. I don’t think anyone in my neck of the woods had a clear idea of who Howard Hawks was during the early 50s, but three of his films — The Thing, The Big Sky, and Land of the Pharaohs — had a particular significance in my home town, Florence, Alabama, because the actor Dewey Martin, who had important roles in all three, was said to have come from there. I can even dimly recall a local newspaper ad referring to “Florence’s own Dewey Martin”. Yet now that I’ve tried to research this detail —- which is no easy matter, because Martin’s career as a prominent actor was short-lived — I’m unable to come up with any corroboration. The only biographical information I can find says that he was born in Katemcy, Texas in 1923 and made his first film appearance, uncredited, in Nicholas Ray’s 1949 Knock on Any Door, so if he wound up in Florence at any point in between those two dates, this is a fact that’s now apparently lost in the sands of time, at least outside of Florence.

I’m bringing this up only because I’m interested in trying to determine how certain films registered in my home town when they first appeared. I know that my friends and I felt a special relation to The Thing, The Big Sky, and Land of the Pharaohs because Dewey Martin was felt to be “one of us,” and I believe this had particular significance in The Big Sky, where Martin plays an uneducated rural character consumed by racial hatred and a desire for revenge, both of which made him seem familiar to us.

Apart from the fact that my parents attended the premiere, The Sun Shines Bright, another period film, felt somewhat more remote to us, even though it was more closely tied to Southern issues, because it was less a film for kids -— less “fun” and more serious. I should stress, however, that there are also uneducated rural characters in this film — notably those played by Francis Ford (in his final film performance) and Slim Pickins (in his first film performance), two hillbillies who are principally around as comic relief —- as well as characters consumed by racial hatred and a desire for revenge, specifically a group known as the voters of the Tornado district, who come very close to lynching an innocent black boy for the rape of a white woman until stopped by Priest, who threatens them with a gun. Later, when the guilty white rapist is killed while trying to flee, it is the older of these two hillbillies who shoots him, and Priest congratulates him for this by saying, “Good shootin’, comrade,” adding that this saves everyone the trouble of holding a trial — meaning, in other words, that this is a politically correct form of lynching. And still later, all the vengeful bigots who wanted to lynch U.S. Grant Woodford turn up at the polls to vote for Judge Priest, assuring his re-election, and then join the parade of well-wishers who pay tribute to this patriarch in front of his house, carrying a banner which reads, “He saved us from ourselves.”

This is no doubt Ford’s view of his own ideal epitaph, which could be spoken at his own funeral. It reminds me of the way my grandfather once cussed out a black male servant who worked for him when he discovered that he’d been duped by a loan shark —- treating him in the most demeaning way possible, as if he were a stupid child, and then calling up the loan shark with threats and more abuse in order to extricate the servant from his highly exploitative debts. This is the closest I can come in my personal memory to summoning up the way Judge Priest treats U.S. Grant Woodford in his courtroom. Jeff Poindexter, on the other hand — who plays dumb in order to honor Judge Priest’s various quirks, including his paternalism, a trait that’s clear in Stepin Fetchit’s performances in both Judge Priest and The Sun Shines Bright — is quite another matter, and I’m sorry to say that the only echoes of his obsequious manner in my memories are blurred by the racially informed confusions of my own childhood. Making things even more difficult for me is the fact that, in spite of my having grown up in the Deep South and being around many black servants, I’ve never been able to understand large portions of what this actor says because of his heavy dialect. (Whether or not this makes his dialect inauthentic is impossible for me to judge.)

I should add that in between Judge Priest’s stopping of a lynching and his triumphant re-election brought about in part by the potential lynchers is the act that the Ford regards as his key act of moral and civil virtue —- arguably far more important in certain ways, at least in this film’s terms, than his prevention of the lynching. I’m speaking, of course, of his joining a funeral procession for a fallen woman on election day, thereby fulfilling her dying request that she be given a proper burial in her own home town. Once Billy Priest joins this procession, he is followed by almost every other sympathetic member of the community, starting with the local bordello madam and her fellow prostitutes, and continuing with the commander of the Union veterans of the Civil War, the local blacksmith, the German-American who owns the department store, Amora Ratchitt (Jane Darwell, see below), Lucy Lee, Ashby, Dr. Lake, and finally — after the procession arrives at its destination, a black church —- General Fairfield, Lucy’s grandfather, who has up until now refused to recognized his daughter under any circumstances.

There are actually two protracted and highly ceremonial processions in the film, occurring quite close to one another—-the funeral procession for Lucy Lee’s mother and the parade of tribute to Judge Priest —- and the fact that these two remarkable sequences are allowed by Ford to take over the film as a whole is part of what’s so extraordinary about them. Retroactively one might even say that they almost blend together in our memory as a single procession — despite the fact that the first is an act of mourning and the second is an act of celebration —- and this undoubtedly contributes to the feeling of pathos in the film in spite of its overdetermined happy ending.

***

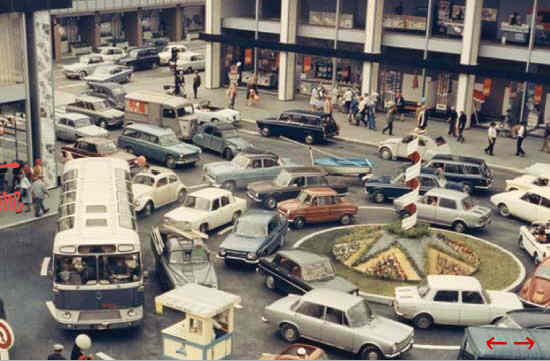

In order to explain some of the reasons why I consider The Sun Shines Bright to be Ford’s greatest film, I’d like to compare it to a few of my other favorite films. Let me begin by citing a film that would seem to be at the opposite end of the spectrum from Ford’s in many obvious respects: Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967). The two-part structure of The Sun Shines Bright is, I believe, very close to that of Playtime insofar as the first half is devoted to introducing various members of a large community who are profoundly and painfully separated and estranged from one another, lost in frustration and loneliness, and the second half is devoted to bringing all these characters together in mutual appreciation and celebration. In both cases, one fairly modest and lone individual helps to bring about this change — deliberately in the case of Billy Priest, accidentally in the case of Monsieur Hulot. In this respect, the continuous carousel of traffic that we see towards the end of Playtime might have as much of a bittersweet edge as the two lengthy processions towards the end of The Sun Shines Bright because in both cases the triumph of community is accompanied by a certain loss of individual identity. In very different ways, Lucy Lee’s mother and Judge Priest become the occasions for communal affirmations that in some ways have more to do with the communities involved than with them as individuals. Lucy Lee’s mother may be little more than a shadow while Judge Priest is the film’s hero, but both are ultimately effaced by the town that honors them, because the town becomes an image of interactive togetherness while these individuals are ultimately isolated and alone.

Another favorite film of mine, Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud, resembles Ford’s in other ways — and not merely because they’re set in the same period (apparently 1905 in Ford’s film, 1906 in Dreyer’s), and tinged with melancholy nostalgia and yearning for still earlier periods. (2) More strangely and paradoxically, I think both films are tragic in feeling despite —- or is it because? — they both have what could be described as overdetermined happy endings. Moreover, both films concentrate at great length on highly ceremonial tributes paid to old men for their life’s work. And both virtually end with figures retreating through doorways (two doorways in Ford’s film), in eerie images that strongly suggest mortality and the ultimate isolation of death.

Although both of these endings can be summarized by the Fordian formula “victory in defeat,” they’re none the less quite different. Gertrud’s victory and her defeat both remain offscreen in the minimalist severity of Dreyer’s final shot of a closed door, whereas both Judge Priest’s victory and the extreme pathos of his isolation, which implies a kind of defeat, are spelled out directly in Ford’s conclusion — albeit made more complex and ambiguous by Ford intercutting between Priest and Ashby with Lucy Lee at Priest’s front gate, the latter silently restraining the former from going to Priest. Ford then records their offscreen exit in long shot as they walk pass Jeff in profile in front of Priest’s mansion, playing his harmonica on the front steps. In other words, both victory and defeat are represented but not shown in our interminable view of the door that closes behind Gertrud after she waves goodbye to her friend, whereas intimations of both defeat and victory are expressed successively in Ford’s final shots: Judge Priest in his apotheosis as a paternal hero, being celebrated by his entire community, whites and blacks alike, says, “Jeff -— I gotta take my medicine, I gotta get my heart started” (a running gag which means that he must once again retreat to his bottle, like a helpless infant), and, turning his back on his community, which also, in the gesture of Lucy Lee, chooses to leave him in his isolation, marches stoically towards his lonely death (a kind of defeat), while his loyal servant, also alone yet facing the same community, celebrates his master’s apotheosis (a kind of victory).

***

Ultimately, what the film may be expressing is neither celebration nor lament, perhaps just simply affection for cantankerous individuals who exude a certain sweet pathos because history has somehow passed them by —- as someone says in the film, I believe in reference to the Confederate veterans, “the doddering relics of a lost cause”, which also suggests The Southerner as Everyman. This implicitly suggests a certain darkness as well as lightness —- which is why the local blacks serenade the judge with “My Old Kentucky Home,” the first line of which is, “The sun shines bright” — and yet this is a film bathed mainly in the melancholy of twilight. For to emphasize and focus on lost causes as opposed to causes that still might be won assumes a certain abstention from politics associated with defeatism — one reason among others, perhaps, why the Civil War plays such a central role in American history as well as in Ford’s work. (In a way, the fact that Judge Priest is a Confederate veteran who is also friendly with many Union veterans nearly sums up his overall relationship to Fairfield as a community.)

***

Although Ford has with some justice been called both Brechtian and dialectical, he has also more debatably been called a liberal and leftist filmmaker. However appropriate this description might be to the impact of his films during the 1930s, I’d like to argue that in The Sun Shines Bright Ford is better described as conservative or a reactionary, albeit one with certain progressive convictions. This is also true of the orientations of some of the cinephiles who value him the most — a list that would include, among others, Tag Gallagher, Gilberto Perez, Maurice Pialat, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, and Michael Wilmington. For what I’m describing as conservative and reactionary in this context means devoted to a certain idea of tradition; it also entails a certain view of human nature that is relatively pessimistic.

I think this can be seen more easily if one compares The Sun Shines Bright to two other low-budget Hollywood black-and-white pictures of the same period that I would describe as authentically liberal. One of these, Jacques Tourneur’s Stars in My Crown (1950), is commonly viewed as liberal, and the other, Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953), released the same year as The Sun Shines Bright, is commonly viewed as right-wing — some would even say fascist because of its treatment of communist spies as standard-issue gangsters and its sympathy for an uneducated woman who expresses unreasoning hatred for them. But I should stress that my definitions of ideology throughout this essay are dependent almost entirely on what I believe their ideological significance was in America when they first appeared, not on what they meant or mean in a European context. And from this vantage point, it’s important to recognize that J. Edgar Hoover’s objections to Pickup on South Street (provoked in part by Richard Widmark’s sarcastic remark to a policeman in the film, “Are you waving the flag at me?”) were — and are —- far more pertinent than Georges Sadoul’s. And both of these films are, in my opinion, radically liberal, whereas The Sun Shines Bright qualifies as either conservatively liberal or (more apt, I think) as liberally conservative.

On the level of plot, the most striking similarity between The Sun Shines Bright and Pickup on South Street is the issue of where a disreputable woman will be buried and whether or not her own wish to be buried somewhere respectable will be honored. There’s a certain amount of pathos and irony that we feel about the expression of this wish in both films, but this is more keenly felt, I believe, in Fuller’s film than in Ford’s. One reason for this is that Thelma Ritter’s Moe — a professional informer in Fuller’s film who makes her living by giving information to the police — is one of the most touching and authentic characters in all his work, and an interesting test case for his radical humanism. So the issue of how someone like Moe is treated in the wider world, even as a corpse — felt especially (and, within the film, uniquely) by Widmark’s character, Skip — is arguably an Old Testament issue, profoundly Jewish in both its sense of exclusion and its sense of justice, while the issue of how Lucy Lee’s mother is treated posthumously is a Christian issue, underlined by Judge Priest’s sermon about adultery and forgiveness. In this case, holding a proper funeral is the community’s way of doing penance for its own sins in ostracizing this woman while she was alive, thereby revising its somewhat tarnished view of itself. This issue never comes up with Fuller’s Moe, not only because she never even has a funeral — the only issue is whether or not she gets buried in Potter’s Field —- but also because no one apart from Skip cares enough about her to bury her elsewhere. By contrast, Lucy Lee’s mother, who lacks even a name, is, as I’ve already stated, scarcely more than a shadow. (Maybe she’s something more than that for Lucy Lee, but from all that we see, the portrait of her grandmother plays a more significant role in defining her identity than the life of her mother.) The moral importance of where and how a discarded woman is buried is clear in both films, but Pickup on South Street has a more radical expression of loyalty by one pariah for another because Skip and Moe are more culturally estranged and socially isolated than any prostitute could be in Ford’s film. Perhaps one could go even further and argue that there is more sensitivity towards the issue as a class issue in Fuller’s film.

The most interesting parallel between Stars in My Crown and The Sun Shines Bright is the prevention of a lynching by the film’s leading character —- a minister in Tourneur’s film, a judge in Ford’s, although, as the judge’s name suggests and his climactic sermon confirms, the latter is in some ways a lay member of the clergy. By the same token, Josiah Doziah Gray (Joel McCrea), a minister, becomes a man of law on many separate occasions in Stars in My Crown, and his successful effort to discourage a band of the Ku Klux Klan from lynching Uncle Famous Prill (Juano Hernandez, see below) has many things in common with delivering a legal brief. In fact, it’s an action which apes that of a lawyer — the recitation of an imaginary will by Uncle Famous that Gray is pretending to read, using a blank sheet of paper — which ultimately shames the mob into retreating. Significantly, we only learn that this will is Gray’s own invention after he succeeds in disbanding the group of men, once the film’s narrator, John Kenyon (Dean Stockwell), a foster child of Gray and his wife, looks at the discarded sheet of paper.

Just as Ford clearly identifies his own practice with that of Judge Priest, I believe that Gray’s ruse on this particular occasion is a perfect illustration of Tourneur’s own aesthetic of mise en scène, predicated on both a pronounced feeling for absence and a profound trust in and respect for the imagination of the spectator to fill that absence. In a way this ruse on Tourneur’s part, a bit like a magician’s trick, is as radical as Fuller’s sympathy for Moe because it implicitly places the audience on the same plane as an unsympathetic lynch mob and then trusts this mob’s good nature as well as its imagination to pacify its own violent impulses. Judge Priest, by contrast — an armed crusader more than a magician —- starts off by trying to reason with the crowd but ultimately has to depend on the threat of violence by pulling out his revolver to stop the lynching. Even if the potential lynchers wind up improbably celebrating him a day later by carrying the banner, “He saved us from ourselves” — another example of religious terminology, like “priest” — this act of saving implicitly comes out of the barrel of a gun.

***

As a Southerner, it’s very hard for me to reconcile all my contradictory feelings about Ford in The Sun Shines Bright, but I’m not sure that there’s any necessity for me to do so. Recalling Gertrud again, I think that some works are great because of the challenges they offer to our beliefs. William Faulkner — who of course was a Southerner himself, unlike Ford — has just as many contradictions as Dreyer and Ford, and we don’t value him any less because of them.

In a memorable lecture about Ford at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film — given last spring by Kent Jones, with interjections by Gerald Peary — the point was made that for every celebration of war and battle in Ford one could counter with examples that sow serious doubts on these celebrations. Similarly, alongside the instances of racism —- most noticeable, I would argue, in the indifference shown towards the casting of Native Americans and the languages they speak, which is not an issue in The Sun Shines Bright, and in the absence of any assumption of Native American spectators (3) — are many expressions of antiracist sentiments regarding Native Americans, blacks, and other minorities (or majorities, perhaps, if one considers the black Africans in Mogambo or the Asian characters in Seven Women).

Most of Ford’s films, perhaps all of them, qualify as fantasies of one kind or another, and few are as unabashedly brazen about this as The Sun Shines Bright. I’m not sure how relevant this is to its social effect, because it was such a modest film in terms of its public reception that I can’t imagine it doing either much harm or much good. (Its anti-lynching “message” was completely uncontroversial, even for Alabama in 1953 — and its nostalgia for master-servant relationships, though informed by a great deal of humor and irony, was equally unremarkable for its period.)

Thinking back to She Wore a Yellow Ribbon — which is possibly the first film of his I saw, and which I would argue is one of Ford’s less Brechtian and dialectical efforts —- it’s hard for me to overlook the possibility that some boys who grew up with me in Alabama may have enlisted to fight in Vietnam partly because of the heroic and idealized image of John Wayne, which this film among others contributed to, even if it shows him as more vulnerable than he is in some of the others. I should add that Fuller refused to cast Wayne in The Big Red One, despite Wayne’s own interest in starring in the film, because he thought the image of Wayne in relation to war was false. But Fuller was someone who grew up as a newspaperman and as a soldier, not as a filmmaker, and it might be argued that fantasy played a very different kind of role in his work because of this difference.

“Ford is very interesting as an object for psychoanalysis,” the film critic Shigehiko Hasumi once said to me, going on to suggest that “there’s something traumatic in Ford’s films; I don’t know what it is, but it’s there.” Assuming that this observation is true, it’s another common point between Ford and Faulkner — not to mention Yasujiro Ozu — and I suspect it has something to do with leaving home.

The author’s thanks to Alexander Horwath and Regina Schlagnitweit for their advice and encouragement.

Endnotes

1. Reportedly a scene very much like this one was cut by Fox from Judge Priest, with Stepin Fetchit playing the prisoner — who was known as Jeff Poindexter — and this became the prime motivation for Ford doing a loose remake, even though much of the remaining plot in The Sun Shines Bright is quite different. The only other actor who’s in both films is Francis Ford, and the only other secondary character is Horace K. Maydew — in this case a senator, played by a different actor.

2. This is the approximate date given by Tag Gallagher in his Ford biography, though Joseph McBride in his much more recent biography estimates the setting to be around 1896. Not knowing the reasoning used by either writer, I wouldn’t know how to choose between these dates. [Update, 4/12/11: McBride has informed me that he has discovered that his 1896 estimate was an error; based on internal evidence — including a poster of Theodore Roosevelt seen in the film and a reference to him in the dialogue as well — he now considers 1905 the appropriate date.]

3. In my book on Dead Man (London: BFI, 2nd ed., 2001), I argue that this is a key ethical and ideological distinction to be made between Jim Jarmusch’s film and other westerns.