From the Chicago Reader (July 10, 1992). For more on Endfield, see Brian Neve’s excellent new biography, The Many Lives of Cy Endfield: Film Noir, the Blacklist, and Zulu, as well as my subsequent Reader article about him and my essay “Pages from the Endfield File,” which grew out of the preceding two pieces and is reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics. This particular piece has been upgraded in terms of illustrations. — J.R.

FILMS BY CY ENDFIELD

The role of a work of art is to plunge people into horror. If the artist has a role, it is to confront people — and himself first of all — with this horror, this feeling that one has when one learns about the death of someone one has loved. — Jacques Rivette in an interview, circa 1967

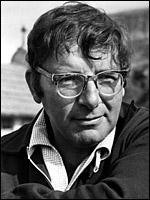

Cyril Raker Endfield, who will turn 78 this November, is the sort of filmmaker auteurist critics like to call a “subject for further research.” To the best of my knowledge, he has directed 21 features — the first 7 in the United States between 1946 and 1951, the remainder in England, continental Europe, and South Africa between 1953 and 1971 — and worked on the scripts for most of them, as well as on the scripts of two Joe Palooka films (apart from the two he directed), a Bowery Boys picture (Hard Boiled Mahoney, 1947), Douglas Sirk’s Sleep My Love (1948), a prison picture called Crashout (1955), Jacques Tourneur’s Curse of the Demon (1958), and Zulu Dawn (1979), a sort of prequel to Endfield’s only hit, Zulu (1964).

Over the month of July the Film Center is screening seven features directed by Endfield, in what I believe is the first Endfield retrospective ever to be held anywhere. It’s a major event prompting some consideration not only of who the man is — and just how distinctive, interesting, and good many of his movies are — but also of why it’s taken so long for his work to be noticed. To put it as simply and bluntly as possible, Endfield’s work has an uncommon intelligence so radically critical of the world we live in that it’s dangerous, threatening that world’s perpetuation. But since Endfield has worked in genres in which such ideas are usually inadmissible and even inconceivable, the very possibility of such insights has been ignored.

You won’t find Endfield’s name in any of the standard auteurist sources, like Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema, and when you do come across his name in a reference book, chances are you can’t depend on the “facts” you’ll find. According to James Monaco’s The Encyclopedia of Film, for instance, Endfield died in 1983. Ephraim Katz’s The Film Encyclopedia erroneously states that he was born in South Africa — an error I was guilty of perpetuating in Film Comment last fall, prompting a friendly letter from Endfield pointing out that his birthplace was Scranton, Pennsylvania, and adding that he has remained an American citizen during all his years as an expatriate.

A biographical sketch based on the little I know is necessarily tentative in some of its details. His first career — reportedly begun when he was a child — was as a magician. (Even today he’s probably better known for his magic and his card tricks than for his movies, especially among magicians.) He refers to magic in some of his movies, though the first such references that spring to mind are all fairly negative — magic as dehumanized nightclub entertainment in Try and Get Me!, as a means of charming and deceiving gullible Africans in Tarzan’s Savage Fury, and as the regular work of a blackmailer in The Limping Man. One should add, however, that negativity about all sorts of things is a powerful, meaningful constant in his work.

Endfield, educated at Yale and at New York’s New Theater School, wrote an article about magic that appeared in Esquire in the early 40s, “I Lobby My Hobby,” in which Orson Welles makes a significant appearance as a valued colleague and friend. It was Welles who gave Endfield his first film job, as an assistant on The Magnificent Ambersons (later, after Welles left to make a film in Brazil and the studio eviscerated Ambersons, it’s said that Endfield may have been responsible for saving one key sequence, a stairway scene between Tim Holt and Agnes Moorehead). From there Endfield went into screenwriting, then entered the Army Signal Corps. In 1945 he began directing “Passing Parade” shorts at MGM, among them The Great American Mug (about barbershops of the 1890s), Magic on a Stick (about the invention of the sulfur match), and Our Old Car (a tidbit about producer John Nesbitt). (Magic on a Stick will be shown at the Film Center on July 24 with The Limping Man.) Then came Endfield’s first feature, Gentleman Joe Palooka (1946), followed by the intriguingly titled Stork Bites Man (1947), the reputedly interesting The Argyle Secrets (1948), and Joe Palooka in the Big Fight (1949) — all of which are extremely difficult to find nowadays.

Endfield’s last three American pictures were The Underworld Story (1950), Try and Get Me! (also known as The Sound of Fury, 1951), and Tarzan’s Savage Fury (1952), released after Endfield had left this country. The first two are remarkable noir efforts that will be shown together at the Film Center on July 17; Try and Get Me! — to my mind a masterpiece of the early 50s — will be shown again on July 30. Both are central to Endfield’s Hollywood reputation, and suggest what he might have achieved had he been able to continue working here. But in 1951 he was declared a former communist by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee, and required to furnish the names of former comrades if he was to be allowed to remain in the film industry. Instead he bought a one-way ticket on the Queen Mary; as he put it in his recent letter to Film Comment, “The political enthusiasms attributed to me were already years and years dead, but the sole option of informing still repellent.” Essentially he took the same route as John Berry, Jules Dassin, and Joseph Losey by moving to Europe.

The effect of the Hollywood blacklist was so strong at the time, however, that even working abroad was no easy matter. Endfield’s first five English features — The Limping Man (1953), The Master Plan (1954), Impulse and The Secret (both 1955), and Child in the House (1956) — had to be made anonymously (directing credit was given to a “front,” one Charles De Lautour) or pseudonymously (he was “Hugh Raker” on The Master Plan, credited with both script and direction). After he’d regained the use of his own name (with certain variants, such as “C. Raker Endfield”), he went on to make Hell Drivers (1957), Sea Fury (1958), Jet Storm (1959), Mysterious Island (1961), and Hide and Seek (1963), followed by his two biggest commercial successes, Zulu and Sands of the Kalahari (1965). (His association with Stanley Baker — an actor in Hell Drivers, Sea Fury, Jet Storm, Zulu, and Sands of the Kalahari, as well as a coproducer with Endfield on the last two — characterizes this period.) Then came De Sade (1969), an abortive German-U.S. production completed by Roger Corman and Gordon Hessler, and Endfield apparently concluded his directorial career with Universal Soldier in 1971. In 1978, according to Ephraim Katz, Endfield invented a computerized pocket-sized typewriter.

Though Endfield’s films are always entertaining, viewers who expect to find the usual action-movie security blankets of charismatic heroes and neat psychological explanations are likely to be perturbed — at times even scared and shaken — by their relative absence in his work. Without exception these are upsetting movies with values that are often difficult to separate from Endfield’s negativity and his capacity to depress us. People who go to movies in order to flee distress — and who no doubt expect their evening news to be cheerful and easily digestible as well — are advised to remain safely within their cocoons, miles away from Endfield’s corrosive work.

A social environmentalist, Endfield is interested in how individuals relate to one another and in how groups interact within particular societies and temporary gatherings. (He’s particularly fascinated by the chance encounters on plane flights — The Limping Man, The Master Plan, Jet Storm, and Sands of the Kalahari all begin with people on planes or in airports — the behavior of a group during a cataclysmic crisis is the focus of the latter two movies as well as Try and Get Me! and Zulu.) A keen observer of class differences and (something that’s much rarer) class resentments, he’s much more interested in the ways that people are socially programmed and in how they function in collective situations than he is in individual psychological profiles, and in this respect he’s more a Marxist than a Freudian. (This Marxism doesn’t necessarily make him procommunist, however; the plot of The Master Plan is as paranoid a piece of 50s anti-Red propaganda as one could find.)

Insofar as Endfield has any reputation at all today among film buffs, it’s as an action specialist — and he is a rare master in this realm, both as a visual stylist and as an acerbic storyteller. A flair for suspense and choreographed crowd movements and a taste for macho ordeals and rugged violence run through his work. For those who subscribe mainly or exclusively to this Endfield, Zulu (playing at the Film Center on July 10) is undoubtedly his major work.

An epic account of an attack by 4,000 Zulu warriors on 105 British soldiers in Natal in 1879, Zulu was called racist 28 years ago when it came out, and I deliberately avoided seeing it for that reason. Now that I can report with confidence that it’s nothing of the sort (though I’ve only seen it in a scanned video version), I’m intrigued by the ideological process that misrepresents or ignores nonracist films about black violence (other examples include the 1969 Slaves and the 1975 Mandingo). Invariably such treatment by the mainstream press neutralizes or trivializes these movies.

Zulu is the only Endfield film of substance I’ve seen in which the lack of psychological motivation works against as well as for the film’s social vision. The absence of any explanation for 4,000 Zulu warriors attacking 105 British soldiers may add to the film’s purity as an action spectacle, but it also limits our understanding of the historical context, including the social (as opposed to psychological) motivations of the two principal officers (Stanley Baker and, in his first major film role, Michael Caine).

To my mind, Endfield’s feeling for spectacle and violence is closely tied to his sense of physicality and materiality (which is, incidentally, tied to his sense of sound as well as image), to his ironic and philosophical perspective on all his characters, and to a highly sophisticated apprehension of social environments. I would argue, moreover, that these virtues can’t be reduced to the generic and graphic formalism often associated with Anthony Mann, an otherwise comparable figure (whose beautiful 50s westerns with James Stewart — Winchester ’73, Bend of the River, The Naked Spur, The Far Country, and The Man From Laramie — are also showing this month at the Film Center).

To me the subtitle of the Film Center’s Endfield series, “A Cynic in Exile,” is all wrong. Though “cynicism” may come close to describing Mann’s more conservative vision, the political lucidity and radical power of Endfield’s best work is not compatible with cynicism. A cynic believes that people’s motives are fundamentally bad and selfish, but this hardly describes Endfield’s approach to the motives of the Zulus or the British soldiers in Zulu, which seems a celebration of courage and nobility on both sides of the conflict. “Cynicism” is also inadequate to describe Endfield’s approach to an out-of-work war veteran (Frank Lovejoy) in Try and Get Me! This character falls into a life of crime because he can’t bear the fact that his wife and son have to live without luxuries — and then becomes so guilt ridden about a kidnapping and murder plotted by his hotshot partner (Lloyd Bridges) that he blurts out a confession to a hapless manicurist (Katherine Locke) he’s been dating. Though she may be pathetic and even grotesque, she’s hardly bad or selfish either; the film’s dry treatment of her may border on cruelty but it’s a far cry from cynicism.

This isn’t to say that both these masterpieces — and other Endfield pictures — aren’t full of cynics and creeps; they are, but Endfield views them with a jaundiced eye and complete lack of sentimentality. It might even be argued that in most Endfield films the world tends to be divided between victims and predators, though neither group ends up satisfactorily fulfilling the usual parts played by heroes or villains. In all of Endfield’s best films –and even in a few of his worst, such as Tarzan’s Savage Fury and Mysterious Island — society proves to be so profoundly out of joint that getting rid of a few bad apples scarcely solves a thing. But it would be wrong to assume that this potent pessimism ever approximates the simple misanthropy of an Anthony Mann or a Stanley Kubrick. Cynics remain characteristic inhabitants of Endfield’s universe without his ever persuading us that they’re privileged observers. The point is that Endfield’s lack of illusions about humanity is never used as a pretext for political defeatism, and it never stands in the way of a cogent analysis of how a particular society works. Endfield’s searing social allegories are all about explicitly man-made horrors — and therefore implicitly they can be unmade or remade.

Take the cynic in Sands of the Kalahari, a character whose viewpoint Endfield makes clear is far from his own. This rifle-toting American thug (Stuart Whitman) — an allegorical cold warrior itching to colonialize everything in sight — survives a plane crash in the African desert, then devotes himself to shooting baboons and some of his European companions on the theory that they’re competitors for food and water who’d do exactly the same thing to him if they had half a chance. By the end he’s become Lord of the Baboons, a job for which he seems ideally suited: Endfield ends the movie with him presiding over his dominion, as if this were a marriage made in heaven.

The Master Plan (playing at the Film Center on July 10 with Zulu) postulates a cold-war universe every bit as hysterical and hopeless as the parodic version in The Manchurian Candidate. Though the virtually invisible communist villains are ruthless–they hypnotize a pathetic convalescent American major (Wayne Morris) so he’ll microfilm secret documents for them — the victim’s superior (Norman Wooland), an English colonel, isn’t exactly endearing. When the movie starts we assume that the major’s the hero; gradually the colonel assumes this role instead, but so many other characters are potential spies that any security defined according to nationality is undermined. (The German setting may even make us confuse the communists with Nazis.) When one of the major characters is finally unveiled as a spy, Endfield wastes no time on the person’s motivations. Rather he leaves us with a queasy sense that this is a crazed militarized culture in which everyone is a dupe, a spy, a paranoid schizophrenic, or some diseased combination of same.

Although Endfield takes some sort of writer’s credit on most of his pictures, it’s often hard to determine with any exactitude how much of each picture is actually his. On The Underworld Story he’s credited with adapting Craig Rice’s story, while on Try and Get Me! Jo Pagano, adapting his own novel The Condemned, gets the only script credit. Yet these two caustic thrillers have such similar social visions — both view the American press as a battering ram the wealthy use against the poor, exploiting local murders to whip up emotions and boost circulation while masking their own culpability — it’s difficult to conclude that Endfield didn’t have something to do with the conceptions of both.

Though it’s risky to make too many generalizations about a filmmaker when at least half his work remains out of reach, there’s no question that the seven films showing at the Film Center have many things in common — striking characteristics that not only indicate Endfield’s singular vision but help to account for his relative obscurity. As suggested above, though he worked almost exclusively in the thriller and adventure-story genres, Endfield showed relatively little interest in or patience with certain mutually dependent generic staples: heroes and villains (at least as they’re usually positioned and defined), sympathetic identification figures, and psychological motivations. These “shortcomings” actually work in Endfield’s favor as a social analyst and critic: he objectifies the films’ social terrains and eliminates the sort of social distortions that heroes, villains, and psychological motivations commonly entail.

I’m not trying to idealize Endfield’s approach. It’s possible that his distance from conventional models of entertainment isn’t always or necessarily intentional; and on the basis of what I’ve seen it’s questionable whether his powers as a social critic in the United States were ever fully translated into an English context. (Hell Drivers, for instance, is certainly an engaging and effective American-style English thriller, but how much it has to say about English life in 1957 is another matter; and the way his English work gravitates toward “international” social allegory, in such films as Jet Storm and Sands of the Kalahari, further suggests a loss of specificity with his exile.)

By any standard the plot resolutions in The Underworld Story and The Limping Man are strained. In the first case, the completely unscrupulous antihero (Dan Duryea) undergoes a sudden moral transformation, thereby earning the love of a good woman (Gale Storm) and taking on a belated hero’s mantle in a formulaic happy ending, all within a matter of minutes. In The Limping Man the dreamlike modulations of the mystery plot, about an American war veteran (Lloyd Bridges) returning to London, suddenly dissipate and a silly “it was all a dream” denouement is added — essentially a screenwriter’s cop-out.

In both cases, however, these genuine flaws contribute to an overall disassociation central to Endfield’s role as a social critic — an alienation effect that bolsters our analytical relation to the events of the films and increases their power to provoke and disturb. Not knowing precisely how to respond to certain characters — such as Howard da Silva’s frighteningly cheerful and honest hood in The Underworld Story and a “serious” Scotland Yard inspector who habitually leers at women in The Limping Man — we’re forced to fall back, uneasily, on our own resources.

The absence of any clear-cut hero in Try and Get Me! seems even more purposeful; two-thirds of the way through the film shifts its narrative focus from working-class to wealthy characters, without losing its thematic and ethical focus for an instant. (Indeed, the only flaw here is an awkward Italian spokesman for the film’s morality who gets wheeled into place whenever the spectator’s own conclusions should take over. In his letter to Film Comment, Endfield described the reprise of this character’s sentiments at the end of the film as “one of several battles I lost to those with more power in the post shooting cut than I had been able to muster.”)

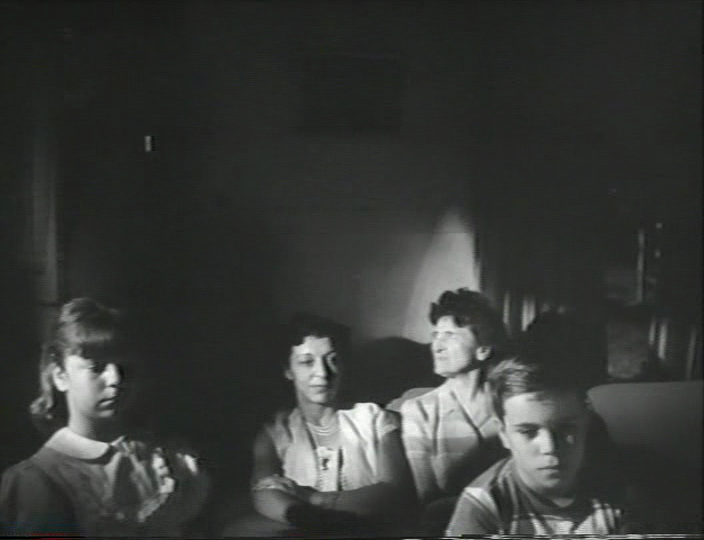

A pronounced talent for abstraction, in relation to both aural and visual space and social milieu, can be felt throughout Endfield’s work. In haunting scenes in both Try and Get Me! and The Limping Man we see entire families seated in dark living rooms watching TV shows we can’t see but whose violence we perceive through the staccato sound effects — emblematic images of the early 50s. No less suggestive is the scene in Try and Get Me! where the tortured war veteran first meets the manicurist: the emotional distance between these shy strangers is brutally expressed by the kissing and embracing of the loud, aggressive couple they’re double-dating with, who stand between them at screen center.

The same visual irony informs a similar composition eight years later, in Jet Storm (showing at the Film Center on July 24): an explosives expert (Richard Attenborough) driven mad with grief by the hit-and-run death of his little girl boards the same flight from London to New York as the hit-and-run driver and secretly plants a time bomb somewhere on the plane. After Endfield treats us to a caustic survey of possible human responses to this crisis, and all the adults on board have tried and failed to persuade the madman to report the whereabouts of the bomb or dismantle it, an eight-year-old boy is enlisted in the effort. At a climactic moment, Endfield frames a loosely hanging phone receiver in the foreground directly between these two estranged characters, parodying the fact of their noncommunication with a symbol of communication that practically dwarfs them both. It’s a representative image of Endfield’s blighted, angry, and absurdist but far from hopeless universe, where the lucidity of his social criticism is often the only vestige of hope and redemption in sight.