From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 1998). — J.R.

The Gingerbread Man

Rating * Has redeeming facet

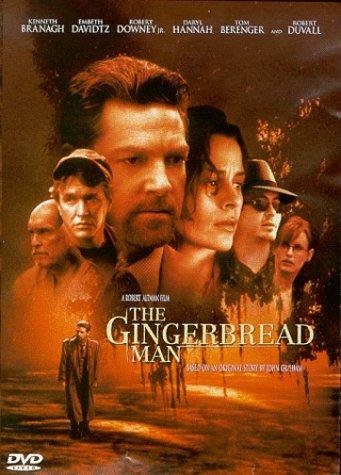

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by John Grisham and Al Hayes

With Kenneth Branagh, Embeth Davidtz, Robert Downey Jr., Daryl Hannah, Tom Berenger, and Robert Duvall.

Some people are going to go to The Gingerbread Man looking for a John Grisham movie, and some are going to go looking for a Robert Altman film. Both are likely to be disappointed.

The alliance may have been a shotgun marriage presided over by desperate commerce, though the movie’s press book works overtime trying to put a positive spin on it: “Both Altman and Grisham champion the causes of Everyman underdogs who are fighting the system. Indeed, in their own different ways, these two artists are mavericks, outsiders-by-choice who examine a system and an orderly regimen that they have long ago abandoned. John Grisham left a successful legal practice for an even more lucrative literary career based in large part on his ability to accurately depict the shortcomings of our legal system and the behind-the-scenes machinations that are a routine part of that profession. And against considerable odds, Robert Altman has bucked the Hollywood establishment for 30 years, continuing to make distinctly personal movies exactly the way he wants to make them, ignoring the marketing driven, lowest-common-denominator sensibilities that seem to determine which studio films actually get made.”

But if The Gingerbread Man didn’t come out of a market-driven sensibility, it’s hard to imagine what else could have led to such a lackluster result — a movie with no driving justification at all. I went in hopes of seeing an Altman film, especially after having heard that a version recut without Altman’s input tested so badly with preview audiences that PolyGram reluctantly decided to release the director’s version instead. Yet the director’s version is recognizable as an Altman film only in a few particulars. I spotted a handful of visual standbys, such as his preference for filming sequences in long shot, with a certain amount of restless drift from pans and zooms, and a taste for motifs derived from TV news reports incidentally seen and heard in various interiors. (The latter occasions much huffing and puffing about a symbolic Hurricane Geraldo, which only arrives toward the end of the picture.) There’s also Altman’s familiar style of recording dialogue that aims for a kind of muttering consistency that’s at times more overheard than heard. (However, there’s little of Altman’s usual TV-derived crosscutting — for which I was grateful, because in other recent Altman films it fostered a rhythmic monotony.) Unfortunately, all these traits tend to work against the thriller components that might have made this succeed as a Grisham movie; even the lack of crosscutting short-circuits the potential for suspense.

My notion of a Grisham movie — based on seeing The Client, The Firm, A Time to Kill, The Pelican Brief, and The Rainmaker — is a movie about lawyers that reminds me of other, usually better Hollywood movies not based on Grisham, and in this respect at least The Gingerbread Man amply fills the bill. The central premise of the plot — which concerns a divorced hotshot Savannah criminal lawyer (Kenneth Branagh) who becomes involved and obsessed with a mysterious waitress (Embeth Davidtz) who’s being stalked by her eccentric fundamentalist father (Robert Duvall) — is that nothing is ever quite what it appears to be. But if you’ve had much exposure to Grisham’s influences at all you’ll realize right away that everything is precisely what it appears to be — because these alleged anticliches have been around at least as long as The Maltese Falcon.

I’d hoped that Altman would in some way ridicule this warmed-over material, as he ridiculed the much better sources of his 1973 The Long Goodbye and his 1988 TV feature The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (even if, according to Altman, the latter won the enthusiastic approval of the play’s author, Herman Wouk). For better and for worse, mockery has been an essential part of Altman’s equipment as a filmmaker since M*A*S*H. But unless one counts a few running gibes against lawyers that can easily be imagined coming from Grisham, Altman basically chooses to treat this hackneyed story straight. Perhaps one could counter that he undercuts the heroism of Branagh’s character, but then he never really establishes that heroism; he merely assumes it, then implicitly chides those members of the audience foolish enough to share this assumption.

The film’s credits read “based on an original story by John Grisham” and “screenplay by Al Hayes” (and the publicity boasts that this is the first Grisham story written expressly for the screen). The press book keeps resolutely silent about who “Al Hayes” is, but there have been rumors in the press that it’s none other than Altman. A couple of clues buried in the same press book suggest that the name may well stand for an amalgamation of Grisham, Altman, and some of the actors. Clue number one: “Jeremy Tannenbaum was the producer who had acquired the rights to The Gingerbread Man from John Grisham many years ago” (emphasis added). Clue number two: “Altman worked extensively on the original screenplay, and then asked his actors to improvise their dialogue whenever they felt they had something different to offer.” The first clue raises the possibility that the original script was a bottom-of-the-barrel Grisham property that went into development simply because of the commercial successes of other Grisham movies, and the second clue suggests that Altman and company tried so hard to pump some life into the apprentice effort that Grisham no longer wanted to be identified with the results.

But of course this is nothing more than simple speculation. Journalistic expertise in such matters is as unlikely to come by as a precise reading of the Will of the American People — the subject of equally confident and baseless punditry in the daily news. The many portents of doom we heard before the release of Titanic matched those about the impending impeachment of Clinton a month later, and the cable news logos promising us a sexy “sequel” to the gulf war proved to be about as prescient as the excitement preceding the unveiling of Speed 2. The etiquette of using rumors and breathless expectations as news appears to have less to do with the probability of their being accurate than with the probability of their taking off — making it something much closer to prospecting for gold or investing in stocks than to performing any sort of public service. So accurate information about what commercial filmmakers do is often as scarce as an accurate understanding of what the public thinks, though given the exigencies of the market and the media, it’s usually considered bad form to admit uncertainty; bald assertion is always deemed preferable.

I can’t say whether The Gingerbread Man is as dull as it is because Grisham’s material defeated Altman or because Altman’s methodology defeated Grisham. I can only hypothesize that the usual Altman impulse to mock genres may have been tempered in this case by monetary concerns — or by not having material substantial enough to undercut.

As for the actors, I regret that Branagh’s relative mastery of a southern accent didn’t make me care more about his tiresome character and that the script decision to get Embeth Davidtz to remove all of her clothes at the earliest opportunity didn’t goad her into revealing anything about her character beyond standard noir styling. Even worse, the lively turns promised by the initial appearances of Robert Downey Jr., Tom Berenger, and Robert Duvall aren’t fulfilled, because the script doesn’t give them much to work with, whether they contributed to it or not. One feels that each of their characters has a fascinating story to tell, but the unraveling of the mystery is so cursory and formulaic that none of these stories ever gets told. In fact, the closest thing to a fully realized character in the movie is Branagh’s red convertible, and the second closest is his cellular phone.