From Sight and Sound, Spring 1975. This is probably the most embarrassing review I’ve ever published (in addition to being one of the very worst) — particularly for reasons given in a quite reasonable letter published in the next (Summer 1975) issue, which I’ve reproduced below, along with my reply. But it’s an instructive sort of embarrassment, which is my main reason for reproducing it now, after some initial reluctance. -– J.R.

Distant Thunder

‘Over five million people in Bengal starved or died in epidemics because of the man-made famine in 1943.’ The title appears over the final shot of Satyajit Ray’s film –- a quasi-expressionistic, rather Bergmanesque vision of silhouetted figures standing on the edge of a precipice, composing a line of seemingly endless breadth behind the camera’s fateful retreat – and is clearly the crucial piece of information around which the preceding 100 minutes have been constructed. Yet the sheer immensity and horror of this unambiguous fact, essentially as unfilmable as it is unimaginable beyond the abstraction of statistics and other metaphors, can operate structurally only as a coda and ‘footnote’ to the rest of the discourse, even if it paradoxically comprises this discourse’s raison d’être. Read more

From the March-April 1976 Film Comment. I’m somewhat irritated today by the hectoring tone of this, but I tend to think most of my arguments are sound — apart from my far-too-facile insistence that Barry Lyndon is a failure, which I would now dispute. — J.R.

So BARRY LYNDON is a failure. So what? How many “successes” have you seen lately that are half as interesting or accomplished, that are worth even ten minutes of thought after leaving them? By my own rough count, a smug little piece of engineering like a CLOCKWORK ORANGE was worth about five. I’m reminded of what Jonas Mekas wrote about ZAZIE several years ago: “The fact that the film is a failure means nothing. Didn’t God create a failure, too?”

Anyway, what most Anglo-American critics appear to mean by failure is that they were (a) bewildered and (b) bored by their bewilderment. To some extent, I was bewildered and befuddled too. So what? Who says we have to understand a film back to front before we can let ourselves like it? “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,/But in ourselves, that we are underlings.”

London critics got to see BARRY LYNDON at least a couple of weeks before their New York counterparts, so the contrasts and comparisons that were drawn were somewhat different: while most of the former chastised Kubrick for his beautiful images before going on to rave about HARD TIMES (known over here as THE STREETFIGHTER) or A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE, the latter were usually more equitable in establishing that BARRY LYNDON and LUCKY LADY were both failures, leading the unwary to suspect that they might as well be equivalents. Read more

From the March 26, 2004 Chicago Reader. This may help to explain, at least in part, why I had no desire to see the Coens’ other remake, True Grit. (Two other reasons that come to mind: I didn’t like the original and I’m sick of American revenge plots, offscreen as well as onscreen.) — J.R.

The Ladykillers

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen

Written by the Coens and William Rose

With Tom Hanks, Irma B. Hall, Marlon Wayans, J.K. Simmons, Tzi Ma, Ryan Hurst, Diane Delano, and George Wallace.

The day after I saw the Coen brothers’ remake I watched the original — the Ealing Studios’ The Ladykillers, a popular 1955 English classic directed by Alexander Mackendrick a couple of years before he directed Sweet Smell of Success in the U.S. I’d taped the original over a decade ago, long before American Movie Classics started recutting features and inserting commercial breaks. AMC may assume that any film in which English is spoken is somehow American, but The Ladykillers, scripted by William Rose, is so thoroughly English I doubt its humor could be fully understood without reference to the English character or 20th- century English history. Read more

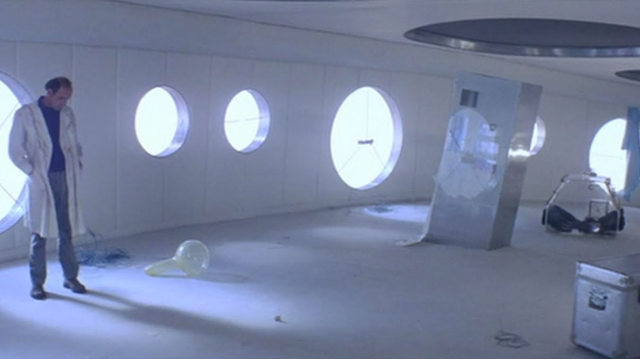

From the Chicago Reader (January 12, 1990). I was disappointed to hear from one of the audio commentators on the Criterion DVD of Solaris that he regarded the lengthy highway sequence as one of the film’s “weaker” sections; for me it’s one of the highlights, both as a provocation and as a “musical” interlude that becomes an occasion for hypnotic drift. — J.R.

SOLARIS **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

Written by Friedrich Gorenstein and Tarkovsky

With Donatas Banionis, Natalya Bondarchuk, Yuri Jarvet, Vladislav Dvorzhetsky, Anatoly Solonitsin, and Sos Sarkissian.

“We take off into the cosmos, ready for anything: for solitude, for hardship, for exhaustion, death. Modesty forbids us to say so, but there are times when we think pretty well of ourselves. And yet, if we examine it more closely, our enthusiasm turns out to be all sham. We don’t want to conquer the cosmos, we simply want to extend the boundaries of Earth to the frontiers of the cosmos. For us, such and such a planet is as arid as the Sahara, another as frozen as the North Pole, yet another as lush as the Amazon basin. Read more

Part of my 1987 application for the job of film reviewer at the Chicago Reader consisted of writing three long sample reviews for them in March and/or April — only one of which was published by them (Radio Days), although, as I recall, they paid me for all three. (Writing my pieces in Santa Barbara, I was limited in my choices of what I could write about.) I only recently came across the two unpublished reviews, of Platoon and Round Midnight, in manuscript, although I recall that I did appropriate certain portions of them in subsequent reviews. Otherwise, the first publications of these pieces are on this site. — J.R.

**PLATOON

Directed and written by Oliver Stone

With Charlie Sheen, Tom Berenger, Willem DaFoe and Keith David.

“I mean, you know that, it just can’t be done! We both shrugged and laughed, and Page looked very thoughtful for a moment. “The very idea!” he said. “Ohhh, what a laugh! Take the bloody glamour out of bloody war!”

Michael Herr, Dispatches

The myth of lost innocence that permeates American movies like some omnipresent air freshener ultimately has a lot to answer for. Read more

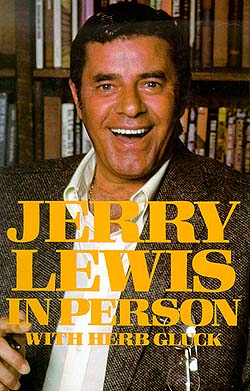

A book review published in the Village Voice (January 25, 1983). The version below restores some of the details deleted by an editor. — J.R.

JERRY LEWIS IN PERSON

By Jerry Lewis with Herb Gluck

Atheneum, $14.95

As a longtime Lewis fan who has lived in Paris, I have less curiosity about the French passion for him than most Americans. The unbridled sweep of the all-American ego at its most infantile and traumatized has always been an object of awe and fascination for the French; think of their celebrations of Poe and Faulkner, H.P. Lovecraft and Orson Welles. Call Jerry Lewis “America” (or vice versa) and you have a recognizable psychosexual object that signifies something more than slapstick and telethons. You also have an explanation for why some part of us despises the man — for rubbing our noses into potential traumas we claim to have outgrown, postulating his hysterical comedy as the literal cutting edge of our equilibrium.

One doesn’t ordinarily turn to an as-told-to show-biz memoir for extended self-analysis. But Jerry Lewis In Person exudes an uncomfortable candor that may actually endear Lewis to some of his detractors, while making admirers like me squirm a bit. The childhood sections which predictably dominate depict not only the lonely New Jersey misfit I expected, but also the street-smart chutzpah of a semi-abandoned tough guy who dreamt of murdering his grandfather, killed his cat in a rage when he was five, hated his show-biz parents for not even showing up to his bar mitzveh, and habitually socked anti-Semites and other wise guys (including his high school principal) in the mouth. Read more

The third chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. To set the context, the book’s previous chapter is called “Some Vagaries of Distribution and Exhibition”. — J.R.

A much more common and systematic method of obfuscating business practices in the film industry, especially in blurring the lines between journalism and publicity, is the movie junket. Here’s how it generally works: a studio at its own expense flies a number of journalists either to a location where a movie is being shot or to a large city where it is being previewed, puts the journalists up at fancy hotels, and then arranges a series of closely monitored interviews with the “talent” (most often the stars and the director). The journalists are then expected to go home and write puff pieces about the movies in question, run in newspapers and magazines as either reportage or as a classy form of “film criticism.” If these journalists don’t oblige — and sometimes obliging entails not only favorable coverage, but articles with particular emphases set by publicists, articles that screen out certain forbidden topics and hone in on certain others — then the studios won’t invite them back to future junkets. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 20, 2004); I revised this slightly in June 2011. — J.R.

Revolution ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Stephen Jones

Written by Bob Avakian

With Avakian.

Queimada **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Gillo Pontecorvo

Written by Franco Solinas and Giorgio Arlorio

With Marlon Brando, Evaristo Marquez, Norman Hill, and Renato Salvatori.

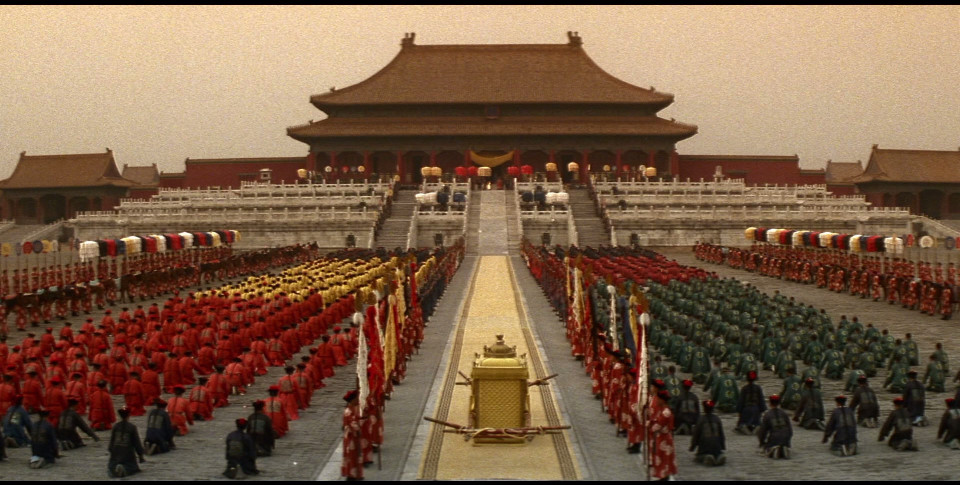

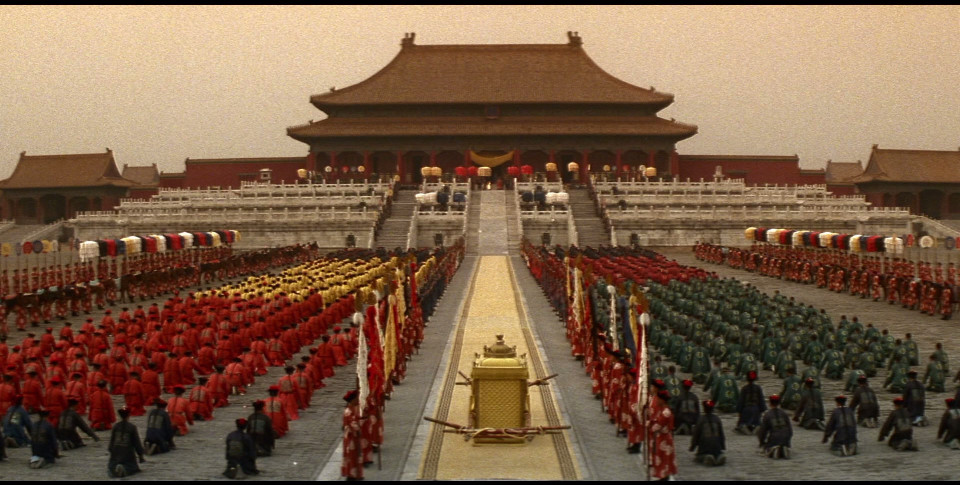

The Last Emperor **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Mark Peploe and Bertolucci

With John Lone, Joan Chen, Peter O’Toole, Ruocheng Ying, and Victor Wong.

August is traditionally the month when films people don’t know what to do with surface, a time when those films are less apt to be noticed. This August three of these films happen to be about revolution. Actually Revolution, showing Wednesday at the 3 Penny, isn’t a movie but a DVD of the first 136 minutes of a long, four-part lecture by Bob Avakian, chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party USA, in what is reportedly his first public appearance since 1979. The other two are director’s cuts of celebrated movies, both being screened here for the first time. Marlon Brando wrote in his autobiography that Gillo Pontecorvo’s Queimada (1969), showing several times this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, contains “the best acting I’ve ever done,” and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987), screening August 28 at Facets Cinematheque, won five Oscars, including those for best picture and best director. Read more

An unpublished essay written in June 1988 for the Chicago Reader. One of my few regrets about my 20 years at the Reader, unlike the year and a half I spent (1979-1981) at New York’s Soho News, was that whereas the latter allowed me to review books and movies concurrently, the Reader was interested in me only as a film reviewer, so any attempt to write about books for them was discouraged. I did make a point of reviewing two of Thomas Pynchon’s late novels for them (Vineland and Against the Day) –- having previously reviewed Gravity’s Rainbow for the Village Voice and having much later reviewed Mason & Dixon for In These Times between the two Reader reviews (all four of these reviews, incidentally, plus my earlier review of The Crying of Lot 49 for a college newspaper, can be accessed on this site).

I wrote the piece below on spec when Michael Lenehan was the paper’s editor and he told me I’d have to do a lot of rewriting before it could be published, so I bowed out. Read more

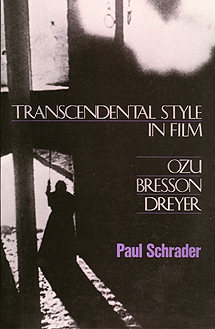

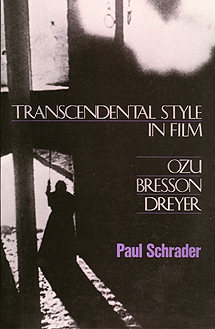

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1972). I like the recent second edition of this a lot more — enough to have given it a blurb that’s used in the ads, and not only because Schrader cites me in his new introduction about “slow films”. — J.R.

TRANSCENDENTAL STYLE IN FILM: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer

By Paul Schrader

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, $10.00

Modesty and caution are not exactly what one expects to find in a book with this title, on these three directors; but ironically, one of the chief limitations of this comparative study is that these qualities often seem to predominate over everything else. The first ‘step’ of transcendental style,for instance, is defined as follows: ‘The everyday: a, meticulous representation of the dull, banal commonplaces of everyday living’ or what [Amédée] Ayfre quotes Jean Bazaine as calling “le quotidien”.’ Not quite a double redundancy, but close enough to make one wonder why this passage and so many comparable ones suggest a critic walking on eggshells.

Although it is nowhere identified as such, Schrader’s extended essay has much of the look, shape and sound of a doctoral dissertation [2013 note: I believe that this was in fact a Masters’ thesis]. 194 footnotes are appended to 169 pages of text, and each step of the argument proceeds like a slow-motion exercise in which every inch of terrain must be defined and tested before it can be touched upon. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 13, 1998). It seems like there are some cinephiles around who still regard Dogme 95 as an honest-to-Pete aesthetic position and not as a lucrative business, ignoring that as far back as 2000, official Dogme Certificates were being sold in Denmark for roughly $1,000 apiece — apparently as a adjunct to von Trier’s main form of income, his ongoing porn-film business (which has also been widely ignored). — J.R.

The Celebration

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Thomas Vinterberg

Written by Vinterberg and Mogens Rukov

With Ulrich Thomsen, Henning Moritzen, Thomas Bo Larsen, Paprika Steen, Birthe Neuman, Trine Dyrholm, and Helle Dolleris.

In 1961 we wrote this manifesto of the New American Cinema. Eugene Archer was working for the New York Times then, and I showed it to him and asked him if they could print it. He said, ‘No, we couldn’t — maybe the Village Voice could run it.’ Then I understood, of course, that the only kind of manifesto that the New York Times would print would be a press release, not a manifesto at all. In the same way, for an idea to get into the Village Voice today, it has to become not an idea but something else. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 13, 2003). — J.R.

Capturing the Friedmans

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Andrew Jarecki.

It’s disconcerting to be appalled and even slightly nauseated by a masterpiece. But Andrew Jarecki’s Capturing the Friedmans is a documentary, and so it’s disconcerting largely because of its subject matter — it shocks us with the truth.

Yet if Capturing the Friedmans were less shapely and less of a masterpiece, I’d find it less troubling. Both times I’ve seen it I’ve felt that by the end practically everyone associated with the film seems tarnished in one way or another: the ostensible subjects (the Friedmans, an upper-middle-class Jewish family in the Long Island town of Great Neck), the members of their community who helped destroy much of their lives, the filmmakers, and the audience. We’re all tainted by the graphic exposure of family wounds, diminished by what we think and feel — and by what we don’t think and don’t feel. Frankly, I’m not sure whether the film deserves to be applauded or attacked for this.

The film’s story, most of which transpires over a dozen years, begins on Thanksgiving in 1987. Arnold Friedman — a highly respected and popular middle-aged schoolteacher who gives piano and computer lessons at home, and who, as Arnito Rey, led a mambo band in the late 40s and early 50s — is arrested for possessing child pornography and subsequently charged with sexually assaulting dozens of his former computer students. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 29, 1988). Note: The Andrew Noren stills are copyrighted by his estate. — J.R.

THE LIGHTED FIELD

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Andrew Noren.

I’m a light thief and a shadow bandit. I deal in retinal phantoms. Film is illusion, period, however you choose to see it — shadows of human delights and adversities or raging conflicts of emulsion grains. We see only “films” of films, as all of our sight and sensing is illusion, the phantom movies of our encounter with the world, which, remember, is equally phantom, trompe l’oeil of that clown and ghostmeister, the sun.

The lovers, light and shadow, and their offspring space and time are my themes, working with their particularities is my passion and delight. — Andrew Noren

The difference between narrative and nonnarrative filmmaking is a little bit like the difference between team sports and individual exercise. In contrast to a collective game with a beginning, a middle, and an end, personal exercise tends to be more rhythmically repetitive, involved more with process and with cycles than with development, and moves with a steadier pulse that eschews the more unpredictable dynamics of drama and suspense.

Andrew Noren’s lovely 59-minute The Lighted Field — part five of his ongoing work The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse, which has engaged him over the past two decades — belongs mainly to the nonnarrative realm. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). The stills are copyrighted by the Estate of Andrew Noren. — J.R.

Andrew Noren’s first film since Charmed Particles offers 59 minutes of ecstatic delight in relation to the everyday: it’s all black and white and silent, and mainly nonnarrative, but so sensually rich and rhythmically alive that watching it is an almost constant pleasure. Noren calls himself a light thief and shadow bandit, and this pulsing compendium of home-movie moments is charged with musical energy. It differs from Charmed Particles, the previous episode in his The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse, mainly in seeming to have more thematic ambitions and in verging somewhat closer to narrative — none of which is allowed to detract much from the overall beauty and intensity of the filmmaking. (JR)

Read more

Read more

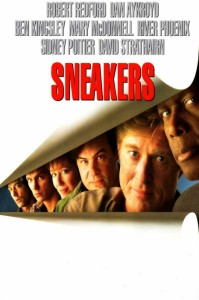

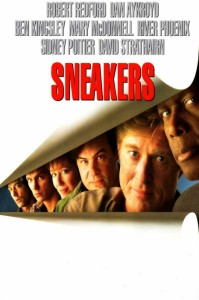

From the Chicago Reader (September 11, 1992). — J.R.

SNEAKERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Phil Alden Robinson

Written by Robinson, Lawrence Lasker, and Walter F. Parkes

With Robert Redford, Dan Aykroyd, Ben Kingsley, Mary McDonnell, River Phoenix, Sidney Poitier, David Strathairn, Timothy Busfield, George Hearn, Eddie Jones, and Stephen Tobolowsky.

Although Sneakers has plenty of artful craft, the principal pleasure of Phil Alden Robinson’s new feature has less to do with art than it does with old-fashioned entertainment. Robinson, you may recall, wrote and directed In the Mood (1987) and the much more successful and better known Field of Dreams (1989), two movies whose basic appeal was founded in nostalgia. Though everything after the prologue and credits in Sneakers is set in the present, the movie reminds us of what movie entertainment used to be about, especially during the 50s and 60s, before inflated ideas about art and significance took over. (I suspect that many of the movie’s high-tech details come from producers and cowriters Walter F. Parkes and Lawrence Lasker, who together wrote the script of WarGames.)

Sneakers can be described in many ways: as a caper movie, a lightweight thriller, a high-tech fairy tale, a boys’ adventure, or a Hitchcockian jaunt dating back to the period before Hitchcock was regarded as a serious metaphysical artist — that is, either before he left England for Hollywood or up to the time he made North by Northwest, but in any case before the weighty French interpretations of his thrillers became coin of the realm. Read more