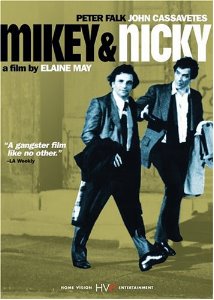

This was written in October 2003 for the DVD released in 2004 by Home Vision Entertainment. DVD Beaver persuasively argues that this edition (currently unavailable, alas) is far superior to the Region 2 PAL release on Odyssey Video. — J.R.

Thanks to an appointment book, I can pinpoint that the first time I saw Mikey and Nicky was on January 7th, 1977, at New York’s Little Carnegie. The experience was a shock. In contrast to A New Leaf (1971) and The Heartbreak Kid (1972) —- Elaine May’s two previous features, both slick (if caustic) Hollywood comedies —- this was a harsh gangster drama in drab urban locations, and, even stranger, a near-facsimile of John Cassavetes’s raw independent features, costarring Cassavetes himself as Nicky and one of his regulars, Peter Falk, as Mikey. The editing was full of continuity errors, the garrulous performances free-wheeling and seemingly full of improvisations (as I then wrongly assumed Cassavetes’ own features were). But the brutal force of an alternately nurtured and betrayed friendship between two small-time crooks over one long night in Philadelphia was so ferocious that it left me shaken as well as bewildered.

The second time I saw the film was in 1980, when I programmed it for “Buried Treasures” at the Toronto Film Festival; this inadvertently became the world premiere of the film’s final version. The film looked even stronger, but most of the continuity errors had magically vanished. It was only later that I discovered that the original release version wasn’t May’s final cut but a cobbled-together version put out by Paramount. It was released after a dispute between the studio and the writer-director about the two years she’d already spent editing the 1.4 million feet of footage she’d shot, which culminated in her psychoanalyst helping her to remove some of the reels and hiding them somewhere in Connecticut. According to Janet Coleman — who reports these bizarre details in her history of improvisational comedy, The Compass (Alfred A, Knopf, 1990) — one can start to appreciate the sheer mass of the footage involved if one considers that 475,000 feet were shot for Gone With the Wind.

A friend who’d worked for May at the time told me she’d been editing the film in all sorts of different ways, and the way she’d been pursuing when the studio took the footage away from her was to splice together all the best line readings without paying any heed to continuity. And my misimpression that the film was partially improvised was also corrected; the script revealed that virtually all the dialogue had been written in advance.

In fact, Mikey and Nicky had started out as a play, and according to Coleman, May had already been working on a play with that title in Chicago back in 1954. There was also some reason to believe that the plot was inspired by an incident involving her older brother, Louis Berlin, back in Philadelphia, her birthplace. And there are other likely personal references. As was noted by Stanley Kauffmann in 1977 — who called Mikey and Nicky “the best film that I know by an American woman” — the film’s title echoes the name of May’s longtime associate Mike Nichols, with whom she’d formed a famous comic duo. (More recently Nichols has employed her as a writer when he directed The Birdcage and Primary Colors.) Even a detail in a speech by Mikey towards the end of the film—about his kid brother losing all his hair —- may have been prompted by Nichols having lost his hair as a boy.

A certain amount of guesswork becomes necessary, because May has avoided interviews about her work almost as rigorously as J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon. But I hasten to add that, well over a quarter of a century later, Mikey and Nicky speaks pretty well for itself — and in fact always has, even in its original scattershot version. It even has clear links to May’s other features. All four of her films to date include the same obsessive theme, the secret betrayal of one member of a couple by the other. The first two of these couples are newlyweds (in A New Leaf and The Heartbreak Kid) and the second two are heterosexual men and best friends (in Mikey and Nicky and the underrated Ishtar) — a Jew and a Gentile in both cases. But only in Mikey and Nicky is this theme pushed to its limits, beyond comedy.

It’s a betrayal with many fluctuations, hesitations, reversals, and ambiguities, and May might be the least sentimental woman storyteller since Flannery O’Connor in her stark refusal to sweeten the pill. If her relentless realism evokes the epic sweep of Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, her narrative still manages to cram a lifetime of troubled friendship, rivalry, money, and pain into the vicissitudes of a single night. And when women figure in the pivotal margins of this tragic tale, May is every bit as merciless as she is towards her two leads, whom she clearly loves as well as fears.